Examine your sentences. Use strong verbs wherever possible. Use the active, not the passive, voice. Try not to use the same words everyone else uses, unless you have a particular reason for making your piece flat. Flat is not what usually works, because flat is boring.

Examine your paragraphs. Do they lead from one to the other in a way that makes sense? Does each paragraph carry an interesting thought, a wonderful sentence, a joke, an astute observation, something to mull over? You do not have to have all of these in the same paragraph. George Garrett advised us to touch base with each of our senses (sight, sound, touch, taste, and smell) on every single page. It is good advice.

If your piece contains chapters, ask yourself if you have started and ended them at the most effectual points. Until you reach the end of the piece, you want each chapter to tantalize the reader into the next chapter. This is called narrative drive. It was not always seen as essential, but today it is essential. Without narrative drive, a story withers on the vine.

As I have said a number of times before, reading is how you learn to do these things. Read the great books of the past. Read current books, but choose them pickily, looking for those that may inspire you or show you new ways to do things. Read books in translation to expand your understanding of what a book can do. And, I say again, reread, and do so more than I do.

Cherry on Style

- On Style…

- …And How To Get It

- Everybody Wants More Than Just One Thing

- Desire is Complicated

- Whatever Happens, Happens Somewhere

- A Gun in the First Act

- The Shortest Distance Between Two Points Is a Metaphor

- The Head and the Heart

- Put the Pedal to the Metal

- In the Middle of Things

- Daydreams in Dresses

- Menacing Middles

- Cut the Cord

- Imagined Endings

- Revise Until You Drop

Having said all this about short stories and novels, we must recognize that poetry also requires revision. And there is no end to how often a poem must be revised. Meter, rhyme, rhythm, diction, alliteration, assonance, consonance, parallels and opposites, meaning and cartoons, caesurae, formal and free verse, past, present, future, the speaker and the poet (who may be one or two), the universal “we,” the particular “I,” even the aggressive “you,” line breaks, stanza breaks . . . for a longer list, check out Aristotle’s. Each line must be knitted with patience and with the broader subject in mind. Each line must be unified by technique. Yet technique is not the whole of what is wanted. You want the poem to dance, sing, praise, acknowledge, grieve, sigh, console, express alarm, express surprise, express peace, enlighten, disturb, recall, and, well, just and. A short poem can contain the world. A long poem can inspect the world. Poems have to be written with love. Otherwise, they may turn slightly stale or even rotten. The poem must not preach. Silly poems are good only if they are really, really good, and some are. Poems, in general, are about — dare I say it? I do — freedom. All the restrictions, all the knitting and sewing, all the punctuation is about making a thing that flies freely into the sky and the canon.

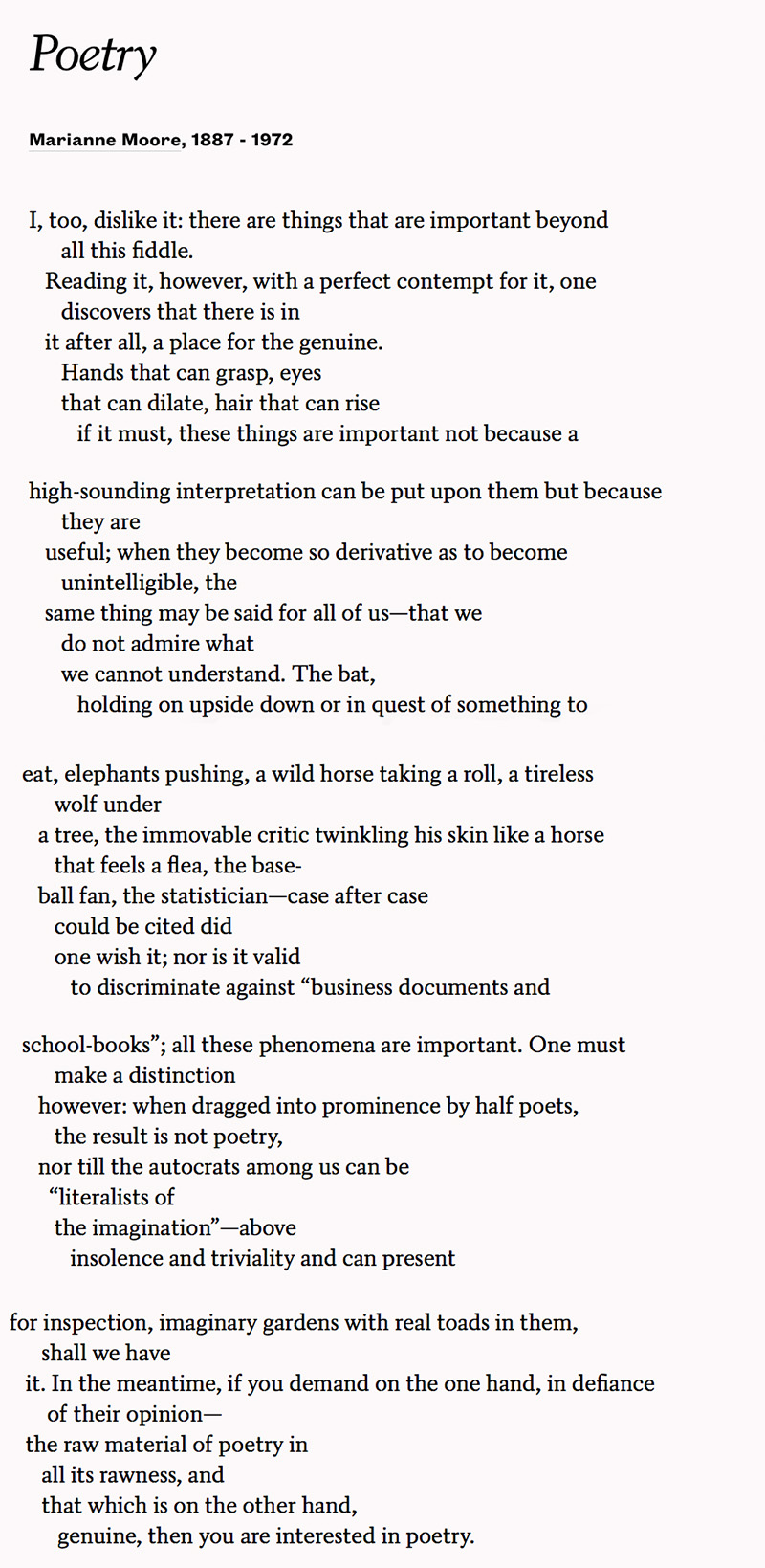

Robert Pinsky, a rather brilliant poet whose work I strongly recommend, wrote an article for Slate, an online publication, in which he analyzed a poem, titled “Poetry”, by another rather brilliant poet, Marianne Moore. Why he asked himself, did Moore keep revising it?

This is how he answered his own question:

The most famous (and most widely lamented) version of “Poetry” is the one Moore published in her 1967 The Complete Poems of Marianne Moore. Many readers, including numbers of Moore’s fellow poets, consider this one of the most egregious examples ever of terrible revision. In that 1967 version, Moore reduced “Poetry” to just three lines:

I, too, dislike it.

Reading it, however, with a perfect contempt for it, one discovers in

it, after all, a place for the genuine.. . . To tease her admirers and critics — or to complicate their responses even further — Moore had it both ways by including the longer poem as a kind of endnote to the three-liner. She published the full, 1924 version (reprinted below), the one preferred by many of her admirers and later editors, in the back matter of that same 1967 Complete Poems with the laconic heading “Original Version.” In various ways, the two incarnations of the poem annotate, challenge, and criticize one another. I think they amusingly challenge and criticize us readers, too . . . Moore, as I understand her project, champions both clarity and complexity, rejecting the shallow notion that they are opposites. Scorning a middlebrow reduction of everything into easy chunks, she also scorns obfuscation and evasive cop-outs. Tacitly impatient with complacency and bluffing, deriding the flea-bitten critic, unsettling the too-ordinary reader, she sets forth an art that is irritable, attentive, and memorably fluid.

And here is the poem as is ultimately stands:

Your poem can grow. It can change. It can shrink. It can become Alice in Wonderland with her ups and downs. It can be considered and reconsidered. It can do almost anything you want it to do as long as you don’t ask it to be dull or clichéd. A poem must never be dull or clichéd.

Who is the speaker in your poem? Yourself? An unidentified “I”? A “you”? A supreme being with a view of all things earthly? A character?

To whom is your speaker speaking? You? Someone else?

Is your poem is search of form? Count syllables and examine your meter. Have you used concrete words that will anchor your poem in your reader’s memory, images that will surprise and stick? Are your line breaks in the right places, whether you are working in form or in free verse? Say them aloud. Say them aloud many times. Your ear will settle the question for you. Is your poem musical, whether that music is rough or dark or bright or sweet or lulling or something like a wind, a breeze, a whisper? There are numerous kinds of music, and a poem has to have some kind of music.

Remember the power of metaphor, simile, image, and allusion. Use these devices. For you, they are worth more than cellphones and Kindles.

Read your poem aloud again and again. Listen to what you hear.

Finally, cut. Cut words, cut punctuation, cut lines that fail to go anywhere, cut repetitions, cut false rhymes, cut anything that might weaken the impact of your poem. Try cutting the first line or two or three. Try cutting the last line or two or three. Cut anything that comes across as fake. A poem’s loyalty is always to the real, the true, the thing itself. Yet it is also true that even expansive poems want to withhold something from the reader so that the reader will remain tied to the mystery of it. Even the clearest, frankest, most up-front poem in the world aims to be a little mysterious. Why? I don’t know. I just know it’s true. Mystery is related to charisma, and the charisma of a poem is what attaches you to it. Mystery, I say, not mufflement or muddlement or inessential secrets or dirty tricks. Mystery.

Now go for a walk. Take a bath. Shake everything out of your head. It will fill up again when you need it to do so. Read a book. Paint something. Clean out the refrigerator. Do the taxes before they light up like fire engines (they always alarm me). Stay calm. Sleep. •

Images courtesy of Poets. Org and ClaraDon via Flickr (Creative Commons).