Both Jews and Muslims consider the pink, snout-nosed animals we know as pigs to be unclean. The question of why this is so has not been conclusively resolved. Did the Koran follow a Jewish rule? Or does the ban stem from the fact that eating raw or undercooked pork meat can contain roundworm larvae, which cause trichinosis? People may have made a connection between pigs and disease, resulting in a fear-based taboo. For the anthropologist Marvin Harris, the main reasons for prohibiting the eating of pork were ecological and economical. Pigs require lots of water and shady woods with seeds, conditions that are scarce in the Middle East.

But the full story may be even more complicated. Whether pigs are considered “clean” or “unclean” has differed from culture to culture, and no clear dividing line based on climate conditions is evident. As a result, it’s difficult to determine what exactly people in the distant past thought about meat. Could it be that this taboo was chosen more or less randomly to create a sense of community among believers of the same religion? To the Egyptian pharaohs, pork was unclean, to the ancient Greeks it was not. The hoggish Romans had a great deal of sympathy for the genus sus, and one pig in ancient Rome even had its own tomb. The inscription reads “Porcella hic dormit” — here rests a piglet. This particular pig lived for three years, ten months and 13 days. Its modern descendants “enjoy” much shorter lives, as they are usually slaughtered when they are between six and ten months old. Christianity’s Saint Anthony, a monk who was born in Egypt, serves as the patron saint of farmers, swineherds, and butchers. Legend has it that at some point he worked as a swineherd, and Hieronymus Bosch painted him with a pet pig at his side. In the Middle Ages, pigs, like many other animals, were held culpable for criminal acts and could be taken to court and executed. All in all, the pigs do not exactly have the best reputation in the Christian tradition — but people still eat them.

The history of human-pig interaction is a long one, and people have both liked and disliked pigs (in fact, “porcophobia” is a term most likely to have been coined by cultural critic Christopher Hitchens in his 2007 book God Is Not Great). Pigs are close to us and distant at the same time. Like us, they are omnivores. They are neither pack animals nor sources of milk: Humans used them for meat from the start. Wild boar sucklings can be domesticated, while domesticated pigs can become feral. Supposedly, the taste of pig meat resembles that of human flesh. There are several records of people undertaking experiments on this subject. I won’t go into detail here, but this idea is related to the observation that firemen don’t like roast pork.

I, on the other hand, grew up in a culture that cherishes pork. Pork knuckle with mustard, sauerkraut, and potatoes is not the popular dish it once was, but you can still find it in some more traditional German venues. Roast suckling is a mainstay of backyard barbecues. Then there is Wurst — sausage, of course — which contains all kinds of things that you may not really want to know about. A peculiar variant is Blutwurst, a sausage skin filled with blood and spices. Pork can even be offered raw, with onions, as a spread. Not to mention Schnitzel, which may be prepared with pork instead of veal. If the statistic is correct, an average German eats the equivalent of 46 pigs during his or her lifetime. 60 million pigs are slaughtered there every year. It’s a little odd to think that the name of such a popular animal is used as a curse word and functions as a symbol for obscenity, stupidity, a person lacking manners, a ruthless capitalist, and exploiter, or someone who indulges in “dirty” sex. Yet surprisingly, a piglet is also considered a sign of good luck (at least in Germany and China). Is this a case of pigs mirroring the dichotomies and complexities of human beings?

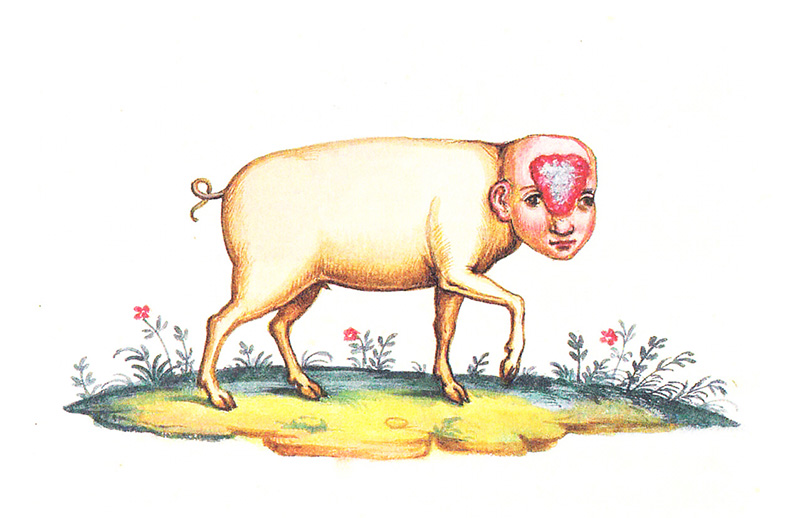

I won’t digress here on how intelligent, curious, and playful pigs are, how courageous and how quick to learn. That they are smarter than dogs. Pigs can even be dangerous to humans. You may have read the news about the human-pig chimera a few weeks ago, which raises the question again of whether limits on science are necessary. Even in art, the idea of pig-human hybrids is a fringe concept — one of the few examples was drawn by Aldrovandi. In fact, pigs may soon provide a bioreactor for spare parts used in humans. A future in which pigs’ hearts can be transplanted into human bodies may not be far off. Before synthetic insulin became available, pig insulin was given to diabetic patients. Any more evidence needed on how closely related humans and pigs are? Maybe the taboos and prejudices in some cultures testify — albeit unconsciously — to the proximity of the two species.

I didn’t even have to let these facts sink in to eschew pork “products.” After living in a Muslim country for five years I simply lost my taste for pork, and it’s certainly not the result of religious indoctrination (by the way, I find it important to mention in these times that nobody has ever has tried to convert me to Islam). So it’s not a halal (Arabic) or helal (Turkish) issue that’s at stake here: I simply became unaccustomed to the taste, I unlearned to like it. In my experience, a long period of intentional or unintentional abstinence lets you perceive something with a fresh tongue or nose. Not eating pork for a while seems to have activated my inner censorship mechanism against it, so to speak.

It’s not even that pork is completely out of reach. While it is classified as haram, or forbidden, under Islamic law and most people have a strong aversion against it, some supermarkets in Istanbul offer packaged bacon. The Eataly gourmet shop sells pork items, and you may be able to spot salami on the menus of high-end Italian restaurants. The people of Polonezköy, a village on the Asian side of the Bosphorus where Poles immigrated in the 19th century, are said to have hunted boars in the extensive forests until not so long ago. And there is an unmarked pork butcher shop, run by members of a family of Turkish Rumeli, or Christians of Greek descent. The pig population in Turkey is supposedly down to a good thousand. It’s not hard to believe. The shop owners lost their license to slaughter pigs a few years ago and they now have to get them from elsewhere.

Pork doesn’t work anymore for me. I should add that I’m not a fan of mutton, lamb, or goat either. When sheep are killed during the Sacrifice Feast in the garden across from the building where I live, I stay away. I just don’t want to see and hear it, even though I find it more honest to kill an animal by hand than anonymously in a factory. Knowing about the ways in which these animals are kept (and killed), I also have reservations about chicken and beef (and other animals that are eaten, such as horse), but it’s not completely off-limits. I sometimes succumb to the smell of barbecued or smoked meat.

Food is just so much more than what we eat. The writer and gastrosoph Jean-Anthelme Brillat-Savarin (1755-1826) is often quoted as saying “Tell me what you eat, and I will tell you who you are.” I know what I eat, but I still don’t know who I am. Maybe the question should be: “Tell me what you don’t eat, and I will tell you who you are”? The result may be more interesting, even revealing. •

Images courtesy of author, Trycatch, via Wikimedia Commons (Creative Commons) and Internet Archive Book Images via Flickr (Creative Commons)