Terrence Malick’s Knight of Cups is an astute observation, a reflection, and commentary that contemplates our contemporary urban islands. The film’s most consistent motif is inversion, a collapsing of the boundaries between the internal and the external, a conflation of self and society featuring a kinetic and nearly constant obsession with the surface vs. substance quandary that has confounded philosophers, artists, and poets for millennia. As I mused in the afterglow of the film, I found myself wondering why, in his recent transition away from the historical and towards the contemporary, Malick selected Los Angeles as his cosmopolis of choice. It took some thinking, but I realized that the last picture to capture L.A. and inscribe it this perfectly was released in 1969, and it wasn’t a film, it wasn’t a novel, it wasn’t an essay: it was an album, Joni Mitchell’s Clouds.

Malick’s worldview, simple but never simplistic, is that we, meaning humanity, are essentially unknowable, transient, part of much larger biologic, neurologic, and anthropologic constructions. We’re amorphous, temperamental, and environmental. We’re like clouds. And, as Joni Mitchell taught us, we really don’t know clouds at all. We are subject to emotional whims, Heideggerian “mood” (Malick studied philosophy at Harvard and Oxford and has translated Heidegger) and entropic decay; our selves are imprisoned in Foucaultian social structures and Wittgensteinian language prisms, and our eternal search for love and transcendence is walled behind the glass of a terrarium (a civilized and citified earth) — as quite literally put to film by one of Malick’s few direct moviemaking forbears, Krzysztof Kieślowski, in the concluding montage of Blue (1993). And Blue (the title of Joni’s almost universally regarded masterpiece) of course forms another link to Mitchell, a woman about whom Q-Tip once reminded us, simply but not simplistically: “Joni Mitchell doesn’t lie.”

In both Knight of Cups and Clouds, and in the streetworlds and microcosmic remnants of nature constituting Los Angeles, one thesis is absolutely clear: We know not the self! And so we try ever harder to define our humanity through how we cut our hair or clothe ourselves or build our domiciles, cobbling together our beings in time out of products and materials and commodities, manipulating our images and e-dentities. We are never the same thing. We float and stir and remain unstable, shaped, and dependent observers — sky-gazers, navel-gazers, and smartphone-gazers. Due to the assailings of mood and moment, we change from day to day, hour to hour, minute to minute. We are inconstant and undestined. We reinvent ourselves and are reinvented by our environs and our circumstances. As Joni Mitchell states on the third track on Clouds (“I Don’t Know Where I Stand”): “All alone in California and talking to you / And feeling too foolish and strange to say the words that I had planned / I guess it’s too early, ‘cause I don’t know where I stand.”

This diorama of dilemma and dependency permeates Mitchell’s album and envelops the titular protagonist of Knight of Cups, portrayed by Christian Bale as one of the floaty-ist leads in filmdom, Rick, a screenwriter (thus at best a contributor, a quasi-writer, subjugated to the image and to the collective) and American flaneur, obeisant only to gusts and urges, impulses and intoxication, indirection and interstices of randomness — earthquakes and home invasions and love affairs. Malick’s camera swoops but Bale often crawls or cowers, retreating from a brother’s punches or a father’s sermons or a woman’s desire to inspire him to some deeper and more meaningful entrenchment of selfhood. He is a fallen prince, a tin angel (and “Tin Angel” is the opening track on Clouds: “Dark with darker moods is he / Not a golden Prince who’s come / Through columbines and wizardry / To talk of castles in the sun) on a midlife quest to regain his former glory, innocence, and purity.

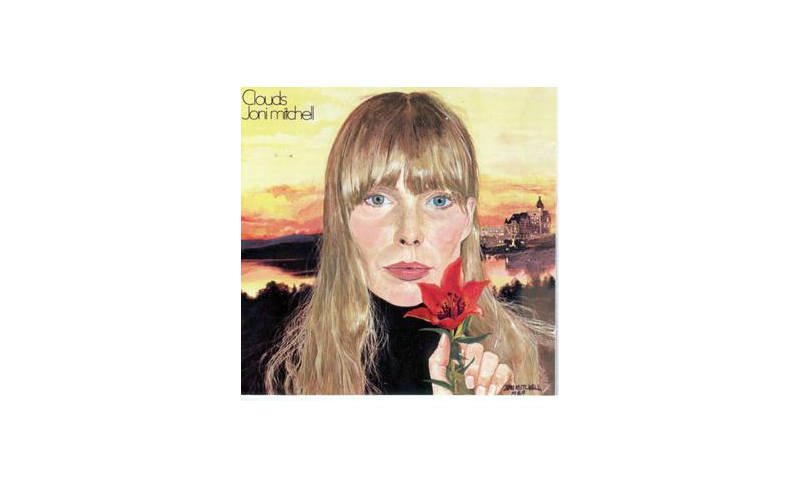

Though Joni Mitchell’s voice has often been called glorious, innocent, and pure, Clouds is not just the songs it contains; It is an aesthetic object, and with its simmering pastel incarnation of the flaxen performer on the album cover, red-flowered and black turtle-necked and golden-tressed, with a sun-hued city in the background (or is it a coastal castle, like something out of Malick’s To The Wonder ?), the record sleeve radiates a classic folk-rock Laurel Canyon vibe; it is an authentic, late-’60s objet d’arte. Mitchell painted the cover art herself, and so it is also a self-portrait, much like Malick’s film, which alludes to the director’s roots in audacious snippets of Midwestern iconography arranged in jarring and unambiguous contrast to the L.A-fixated film as a whole. On Clouds, Joni Mitchell espoused the truth that to be human is to be fleeting (on the album cover, the “m” in her last name is notably lowercased). The lyrics to “Roses Blue,” in particular, haunt almost every corner of Malick’s film, as his is a world of signs and seasons, sorrow and self-pity. Like Mitchell’s song, it has the priestess and the black spells, the zodiac and zen, a protagonist in diminishment and deliquescence, everything right down to the tarot cards and death.

Knight of Cups is arranged into ten sections, with the run of “IV/Judgement,” “V/The Tower,” and “VI/The High Priestess” finding ever-more-fertile ground for comparison in “Roses Blue,” the fifth of ten songs on Clouds, the centerpiece, closing out side one of the album. In sinking down to drown or swim, this song is the moment where Mitchell ponders. Knight of Cups is ponderous; and I mean ponderous in a positive way, though admittedly it’s one of those arthouse films you recommend with qualifiers and waivers. It is unceasingly poetic, balletic, operatic, and most of all downright littoral. Malick’s vision — and Emmanuel Lubezki’s camera — dives into waters both muddy and chlorinated, rivers and aquariums and pools of all sizes and shapes and levels of fullness or emptiness (like human souls), and the divers are sometimes expensively clad humans and other times savage-mouthed canines. But these dogs are not attacking: They are wide-eyed seekers desperate to clamp down on a submerged tennis ball or chew toy (a satisfaction they never achieve). The waters and coastlines, the permutations, morphings and interzones, the cellular and the celestial, it’s all there, from infinitesimal sand grains to the grandeur of the earth’s atmosphere. For sheer ambition and breadth, few filmmakers flat-out aspire to the extent Malick does.

Other than the closing track and source of Joni Mitchell’s title imagery (“Both Sides Now,” a cornucopia of the internal and external in congruence), the other canonical single off Clouds is “Chelsea Morning,” which abounds with Malickian imagery — closed curtains and incense owls, candlelight and jewel-light. And in terms of Malick’s place in the cinematic canon of the moment, Knight of Cups is in many ways a flickering and refracted version of David Cronenberg’s scabrous black comedy Maps to the Stars (perhaps 2015’s best film). It also conjures up resonances of Kubrick’s Eyes Wide Shut and the late Lynchian omnibuses Mulholland Drive and Inland Empire. From Kubrick comes the handsome male lead, the übermensch untethered, no magic mountains to climb in the postmodern sphere, and Bale here even more wordless than Tom Cruise’s piano-haunted and sexually objectified specter. Malick is, like Kubrick, concerned with dehumanization and deeply troubled by our aversion to real connection, by ephemerality and commodification, by threats to the natural world — he is a filmmaker unsettled by fragmentation (Brian Dennehy’s character Joseph, Rick’s father, recites: “You think when you reach a certain age things will start making sense, and you find out that you are just as lost as you were before. I suppose that’s what damnation is. The pieces of your life never to come together, just splashed out there.”), finding humanity only in the transcendental, in short silent respites, in mountains and deserts and secluded unpublic spaces, which are perhaps the most difficult to attain commodity of all in the Southern California of 2017, where for the first time in its history the population of Los Angeles has crested four million people. And like Lynch showing us homelessness, addiction, suicide, and the most vicious objectifications of women by the Hollywood meat grinder, Malick too exposes how we are burned and broken and lost. We not just the city dwellers but the species as a whole, are in need of healing.

The novels of Haruki Murakami and David Mitchell also treat humanity this way, as a species instead of as a series of individuals. They are artistes aware of the Anthropocene, their fictions both cosmopolitan and speculative. But while their worlds are often complex and cornute, there is a yearning for simplicity that manifests itself in Joni Mitchell and Terrence Malick, a deep desire for equal parts Zen and Walt Whitman, for a rustic simplicity, for beaches and oceans and skies. A great alternate title for Knight of Cups would be The Narrow Road to the Deep South(land), as the synergy, or impossibility thereof, between the natural world and the manmade could find no better locale than contemporary Los Angeles (and Las Vegas as well, at least for a short stint in Malick’s film), a city full of legitimately beautiful vistas but ever more impinged upon by our modern, postmodern, technologized simulacra, our increasingly mechanized attempts at beauty (or is it all just superficiality?) and the crowding out of nature by pop culture.

Malick isn’t a satirist like contemporary Italian master Paolo Sorrentino, whose The Great Beauty and Youth mine adjacent ground, but being attuned to the sweeping mechanization that has crept into all that is human makes Sorrentino one of Malick’s few true inheritors. Others might tap David Gordon Green, Andrew Dominik, or Shane Carruth as “post-Malicks” the same way a music journalist or folk-rock acolyte could name a dozen or more post-Joni singer-songwriters, including talents like Leslie Feist, Joanna Newsom, Sharon Van Etten, and Laura Marling. And of course in the directorial realm there is the gifted (and accoladed, a back-to-back Best Director Oscar winner) Alejandro González Iñárritu, who also employs the for-the-ages cinematographer Lubezki, though the Malickian riffs were the weakest and most out-of-place parts of Iñárritu’s The Revenant.

Most of Terrence Malick’s films are set in the past (his superior take on the period depicted in The Revenant is 2005’s The New World), but in Knight of Cups we have the ultra-present, the SLS Beverly Hills, the Vegas nightlife of Cirque-ish aerialists who look simultaneously to be flying and swimming in vaulted spaces above nightclubs, or lounging about the pools of façade-mongering at Caesars Palace. In Joni Mitchell’s “That Song About the Midway” (fourth on Clouds), there are also winged acrobats and sideshows and gamblers, and it concludes with the speaker’s epiphany that she is, much like Knight’s protagonist, “midway down the midway slowin’ down.” Christian Bale was 40 years old for this film, and “Section III/Hermit,” one of the most commented-upon sections of Malick’s motion picture, centers on a playboy vamp deftly inhabited by Antonio Banderas, a man-child who owns and exhibits, who lords over a mansion full of cartoonish excess that points to a Malick every bit as dubious as 1969 Joni Mitchell (the height of her acoustic-pure makeupless Canadian émigré waif period) was of our abiding addiction to spectacle.

Malick is more than just his concern: He is auguring, advising wariness while stopping short of admonition. Knight of Cups is directed by a man who sees humanity going to hell, or at least the perdition of soulless-ness. And it is not just apprehension or fear for her fellow humans in Joni Mitchell, the 1960s avatar of the garden exposing “life’s illusions” as “just another show,” but in the trepidations shared by some of her millennial and centennial descendants, as in Lorde’s skewering and side-eying of the zeitgeist in the 2013 hit “Royals.” Knight of Cups presents us with a torn-up town, a literal one out in the Southern California desert and also the vivisected nature of Los Angeles, what Mike Davis famously called “the city of quartz,” a carved-up real estate puzzle that adheres rigidly to worshipping the god known as The Market, that abuts the homeless (as in Knight of Cups’ documentary-style sequences shot on Skid Row in downtown L.A.), with the most invidious, assimilationist, and atavistic gentrifications.

Bale’s protagonist wallows and wanders through the excesses, the bloodstains, ball gowns and trashed hotel rooms, the private planes and gold-leashed tigers and infinity pools, the drug-induced altered consciousness, a manse literally regal in its opulence and ornamentalism overseen by an uber-cad, comparing women to fruits as all who gather there (including Ryan O’Neal, a shout-out to Kubrick’s Barry Lyndon) prepare to dine off gilded china at Victorian dinner tables straight from the milieu of Sofia Coppola, another auteur of élan casting withering glances at Los Angeles, in The Bling Ring, and at excessive humanity marooned within well-chandeliered drawing rooms in Marie Antoinette. Or, for another analog, think of Knight of Cups as harnessing the ethereal beauty of the establishing shots from Michael Mann’s contemporary classic about the City of Angels, Heat, but without surrounding them with plot and dialogue and traditional acting.

Class is depicted on Malick’s screen but it is done artfully, non-didactically, embodied in image, in bridges and waterways contrasted with studio lots, in a Pacific Ocean adjuncted by Santa Monica beachfront properties with views of streetscapes (a portrait of the now, where streets are basked in butterscotch sun pourings and paved with passersby) and carnival lights (moons and Junes and Ferris wheels, dreams and schemes and circus crowds). Trains pass through that might as well be straight out of Frank Norris’s 1901 naturalist novel The Octopus. There are intermittent crashes and smashings together, totems of violence and violation — a machete, a shattered chair. There are fortune tellers assembled alongside a doctor (Cate Blanchett), a priest (Armin Mueller-Stahl), and a Zen master (author Peter Matthiessen), the scientific and the spiritual, the pagan and the Judeo-Christian, a mashup evocative of the Q-Tip/Janet Jackson/Joni Mitchell collaboration alluded to above, 1997’s “Got ‘til It’s Gone.” There are evocations of the sacred and the profane, the austere and the indulgent, the scientific and the irrational. Brian Dennehy’s aging patriarch crosses abandoned courtyards and poorly attended theater stages, maybe as Falstaff, maybe as Hickey, maybe as something darker and more modernist, evocative of Samuel Beckett or Thomas Mann (a resident of Malibu in his later years).

Dennehy’s paterfamilias rages against the dying of the light, but Bale’s passive lead is abreacted by a series of encounters with a wide variety of women, queens bees and wannabes, party girls and strippers and a married woman. Rick, modelling masculinity as hedonism, is contrasted by a brother (played by Wes Bentley) yearning for a masculinity defined by aggression and strength and redemption, and by a withered husk of a father who lived an earnest mid-century mode of masculinity for too long, resulting in a lost sibling and an estranged mother for his sons. The last two subheadings of this film are “VII/Death” and “VIII/Freedom.” Death comes first, and that is oh, so fitting. Malick’s film is as defiant, inimical, and uncompromised as that inversion. It is non-dialogic and not plot-driven, much more of a symphony or a confabulation than a narrative night at the movies.

In the March 7, 2016 issue of The New Yorker, Richard Brody wrote an essay on the film that veers from the poetic to the philosophical but is mostly about having the type of sublime epiphany Zadie Smith experienced upon exchanging her petulant teenage skepticism of the music of Joni Mitchell for full-grown maturity, understanding, and appreciation of its unimpeachable artistry. “This is the effect that listening to Joni Mitchell has on me these days: uncontrollable tears. An emotional overcoming, disconcertingly distant from happinesss, more like joy — if joy is the recognition of an almost intolerable beauty.”

Knight of Cups contains this same serum, this timelessly triumphant joy, this puncturing of dystopic automatonism with the spear of the sensual and the humane. What appeals to me is the ability of Malick and Mitchell (both born in November of 1943) to make of seemingly earnest or even sentimental things something very un-earnest, something anti-sentimental, something that in every way qualifies as truly original, as insightful and investigative, as interrogative, indelible, and fully instantiated art. •

Feature image created by Shannon Sands, using Clouds album cover art and Knight of Cups movie poster as reference. Images courtesy of DatBot and Film Fan. Other images by Shannon Sands.