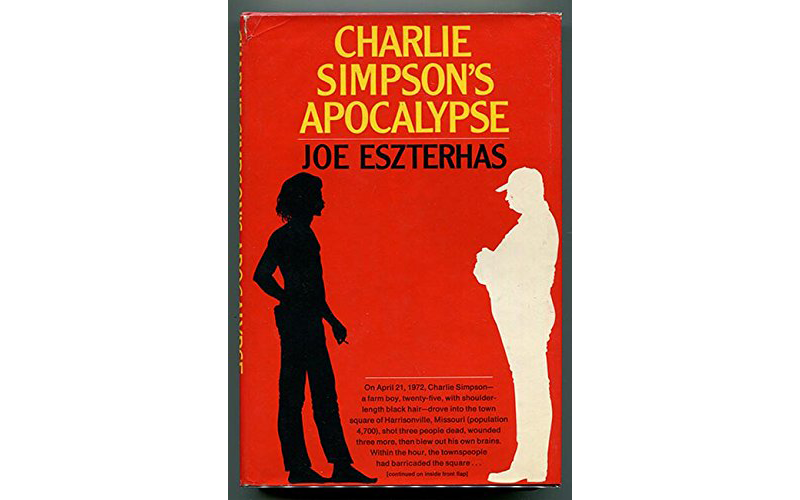

Among the overlooked gems of the influential but short-lived genre known as New Journalism is the curious account of the violent conflict between a small band of country hippies and local businessmen in rural Missouri in the spring of 1972. Uniquely evocative of its era, Charlie Simpson’s Apocalypse by Joe Eszterhas is set in the waning days of the war in Vietnam as America’s heartland is riding its last great wave of prosperity. Within two to three decades, countless Midwestern towns would be decimated by the 1980s farm crisis, the loss of good paying (read: union) manufacturing jobs, and the methamphetamine and heroin epidemics.

At the time, however, town elders in villages like Harrisonville, Missouri were focused on a more tangible enemy in the guise of a few shaggy-haired, weed-smoking ne’er-do-wells — many of whom were disillusioned Vietnam vets — instead of rising land prices, mounting debt, disastrous trade policies, and the rise of corporate agriculture.

Charlie Simpson’s Apocalypse wasn’t entirely overlooked in its day. Eszterhas’s book was a finalist for the 1974 National Book Award, edged out by All God’s Dangers: The Life of Nate Shaw, Theodore Rosengarten’s biography of an Alabama sharecropper turned human rights activist (another forgotten masterpiece). As a runner-up, Eszterhas was in fine company. Other finalists that year included Bob Woodward and Carl Bernstein for All The President’s Men and Studs Terkle for Working. Eszterhas’s original story appeared in Rolling Stone and caught the attention of Tom Wolfe, who included the gonzo-esque piece in his 1973 anthology The New Journalism.

Today Eszterhas is remembered, if at all, as the libidinous screenwriter of the 1980s and early ’90s erotic thrillers Jagged Edge and Basic Instinct. At the top of his game, he was pulling down a record three million dollars per script, a few of which were truly excellent (Music Box, F.I.S.T.). But internecine squabbles with producers and agents and a string of universally derided screenplays (“I speak of Sliver, Showgirls, Jade and other insults,” sneered reviewer Christopher Hitchens) effectively ended his Hollywood career. He returned to book writing, churning out a series of best-selling, self-aggrandizing, and profane Hollywood memoirs (American Rhapsody, Hollywood Animal, The Devil’s Guide to Hollywood) designed to titillate as well as settle old scores. The memoirs have been roundly panned by critics. Who knew Tinseltown is full of greedy, immoral, ambitious, sex-crazed Philistines?

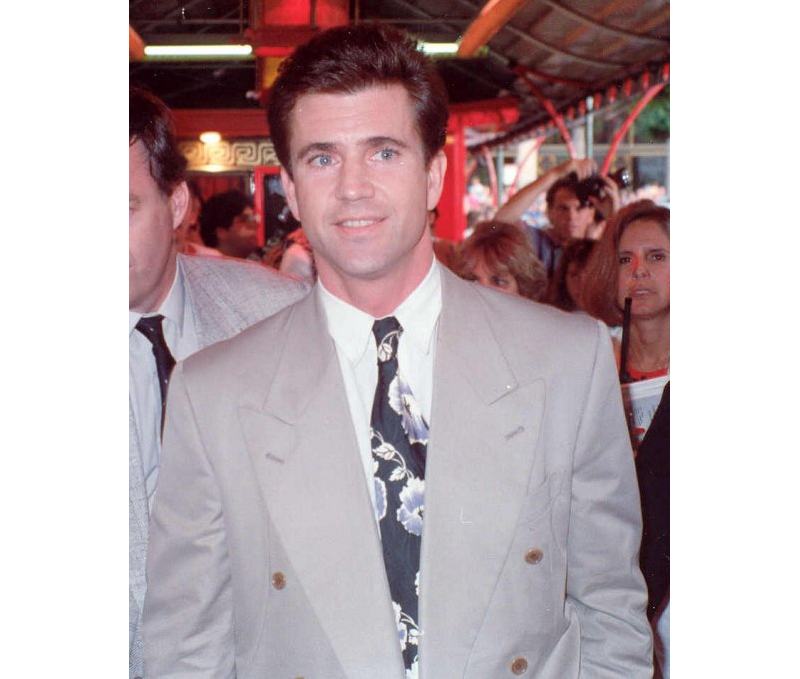

Then Joe met Mel.

As in Gibson. Eszterhas, whose father penned anti-semitic propaganda for the Hungarian branch of the Nazis, is understandably sensitive to anti-Semitic messages and therefore was probably not the best choice of screenwriter for a Gibson production like the unproduced religious epic The Maccabees (dubbed the “Jewish Braveheart”), a film Gibson hoped would convert a substantial number of Jews to Christianity. “I’ve come to conclusion that the reason you won’t make The Maccabees is the ugliest possible one,” Eszterhas wrote Gibson. “You hate Jews.” Their odd coupling is detailed in Heaven and Mel, where the reader is treated to page after page of Gibson’s psychotic, misogynistic, homophobic, and anti-Semitic rants. While Gibson may have come out on top in Payback the film, there are clearly no winners in this sordid revenge tale, and that includes the poor book buyer.

More recently, Eszterhas, now a throat cancer-survivor, has fled Babylon for the Ohio prairie of his youth, accepted Jesus as his personal savior, continued his feud with Gibson, published a born-again memoir titled Crossbearer: A Memoir of Faith which, according to one critic, reads much like an extended bar rant, and started a subscription-based blog, JoeUnchained, a continuation of his recent Hollywood/born-again memoirs, as well as his thoughts on the Trump administration. Eszterhas voted for Trump, but only because the choice was between an “A-hole” (Trump) and a “criminal” (Clinton).

Obviously, Eszterhas, like many artists, was capable of soaring to great literary heights as well as plummeting to unfathomable depths.

Long before his 15 years of Hollywood fame, Eszterhas was a young, hotshot reporter, first at Cleveland newspapers, then for Rolling Stone. József A. Eszterhas grew up a war refugee in Cleveland slums. That Midwest locale proved a boon for the young journalist. While at the Cleveland Plain Dealer, Eszterhas was ringside for various Vietnam War protests and co-authored the first book on the 1970 Kent State massacre. Shortly after that, Ronald Haeberle, an Army photographer, asked Eszterhas if he would like to see a cache of unpublished photographs from the My Lai massacre. Seymour Hersh had just broken the My Lai story, but many Americans refused to believe their troops capable of such atrocities. The photographs verified Hersh’s reporting and, Eszterhas later bragged to an interviewer, helped end the war. When, in the pages of the avant-garde Evergreen Review, Eszterhas criticized the way the Plain Dealer published Haeberle’s photos, he was sacked for disloyalty.

When God closes a door, He opens a window. That window turned out to be in the editorial office of Jann Wenner’s underground music magazine, where he worked alongside such countercultural icons as Lester Bangs, Greil Marcus, Cameron Crowe, and Hunter S. Thompson. The Rolling Stone pieces Eszterhas wrote in the mid-‘70s have never been collected, though they are arguably the best stuff he has produced in any medium. (A prime example is “Death in the Wilderness,” Eszterhas’ reportage of the first shot in the War on Drugs, which became the basis for his second book of 1974. In Nark!, Eszterhas convincingly argued that it was easier and more lucrative for drug enforcement agents to pick on small fries, rather than spend years anonymously going after the harder-to-catch big fish.)

Before long, Eszterhas found himself back in the Midwest, this time investigating the strange goings-on in a small western Missouri town. The setting was flyspecked Harrisonville, a “smalltime place haunted by homilies, platitudes and booshwah,” a daytrip south of Kansas City, whose most notable resident had been Edward Capehart O’Kelley, the man who killed the man who killed Jesse James.

What interested Eszterhas more than the story’s somewhat pedestrian true crime aspects (on April 21, 1972, a local long-haired farm boy, Charlie “Ootney” Simpson, 25, went on a shooting spree in Harrisonville’s town square, killing two police officers and a local businessman and wounding several others before taking his own life) were the story’s countercultural themes. The shooting was the culmination of months of antagonisms between the county’s long-haired “freaks” and the ordinary townsfolk, the so-called rednecks or “necks.”

By the time of the shooting, the Deep South and Upland South, the last redoubts of patriotic American values, were in turmoil. The hippie poison had leeched into the heartland, and the Rotarians, soybean farmers, and town square merchants were both outraged and alarmed.

In 1969, when the film Easy Rider came out, in which slack-jawed yokels shotgunned hippies from the cabs of their GMC pickups, freaks were still a rarity in southern cities, serving mostly as diversionary sport for good ol’ boys who enjoyed nothing better than “kicking hippies’ asses and raising hell,” as the cosmic cowboy Ray Wylie Hubbard discovered when living in Red River, New Mexico. Merle Haggard’s 1969 ode “Okie from Muskogee,” might have been trite and jingoistic, but its lines about waving Old Glory down at the courthouse and not letting “our hair grow long and shaggy,” accurately chronicled the gulf between traditional rural Americans and those San Francisco freak-flag flying hippies they read about in Life magazine.

The ragtag plowboy hippies who occupied the Cass County courthouse square in the spring of 1972 were more than an annoyance to the local merchants and townsfolk. They were deemed a threat to the American Way of Life, all the more so because they were so incomprehensible, even to a veteran reporter like Eszterhas. These were not your New York free speech radicals and tricksters. Nor were they back-to-the-earth Jesus Freaks. (As country boys, they had never left the earth.) They were, rather, disenchanted war vets and aging juvenile delinquents whose many run-ins with the “pigs” had left them with large chips on their shoulders, though with little in the way of an agenda beyond some shady talk of liberating Harrisonville:

They were hometown hippies who primped in the cracked mirror of their egos and saw themselves as more intelligent, more humane, more real than their plastic deodorized elders. They were the victims of a freeze-dried generational racism which would not forgive their long loathsome hair and their scuzzy tramp-clothes. So now, cast in a psychodrama partly of their own design, they grew their hair even longer and let their jeans get grubbier. They asked for it: the audience reaction was confirmation of all their halfbaked theories. They screamed “Fuck You!” with every gesture and found applause in the cops’ teeth-gnashings and housewives’ cringings.

What crackpot beliefs and half-baked notions the freaks espoused were culled from the era’s subversive and largely unreadable literature, in particular Abbie Hoffman’s Revolution for the Hell of It and Jerry Rubin’s Do It!. The group’s leader, Ootney Simpson, likewise had a soft spot for Henry David Thoreau (often called America’s first hippie) and had saved his nickels to purchase a few rocky acres where he hoped to establish his own Midwestern version of Walden. (Ootney was devastated when the craggy landowner got spooked and backed out of the deal.) But by and large the freaks were provincial, unlearned and immensely naïve 20-somethings that sanctimoniously decried racism and opposed the Vietnam War while simultaneously disrespecting women (their favorite epithet for their female high school groupies was “skunks”). If they had an identifiable program, it consisted solely of getting stoned, playing Frisbee on the courthouse square, and irritating the hell out of the ‘necks.

To the ‘necks, the freaks were a worrying symbol of the decline of American civilization, a downhill slide that had commenced with Brown v. Board of Education and picked up steam with the Voting Rights Act and the protests over the Vietnam War. Though what irked the local business and government leaders most — besides the one African American freak who blatantly pitched to woo young, white virgins on the courthouse square — was the hippies’ long, greasy locks. As far as the ‘necks were concerned, shoulder-length hair represented a giant middle finger to hardworking, patriotic Harrisonville residents. Long hair signified subversion, revolution, communism.

The cops’ inevitable crackdown on the freaks escalated tensions. The final straw came after the bogus arrest of several hippies, which forced Ootney to blow his Walden fund on bail. It was all too much for the longhaired transcendentalist. The next afternoon, Ootney snapped. The resultant shooting spree made national headlines.

Eszterhas blamed the rhetoric coming from both sides for the tragedy. “The Abbie Hoffman types were saying, ‘Go kill your parents,’ and the Nixonians in law enforcement were saying, ‘These kids are bums,’” he later told an interviewer. “That fueled this confrontation that ended up in gunfire.”

In the aftermath of the shooting, a few well-meaning attempts were made to bridge the generation gap. Outside experts were brought in to defuse tensions and establish lines of communication, though neither side seemed interested in talking. The ‘necks, in particular, were suspicious of the outsiders and refused to cooperate. They simply wanted the hippies to cut their hair, find jobs, and show some respect for their elders — or better yet, move away. The freaks, meanwhile, just wanted the ‘necks to stop hassling them. Before long, the freaks reoccupied the courthouse square. When the ‘necks had enough of the dithering by police and town officials, they formed a vigilante group. The vigilantes violently retook the square. For a while, the freaks holed up on a nearby farm, where they licked their wounds and plotted their revenge until they quietly drifted away, one by one. In the end, the ‘necks, with their superior numbers, carried the day.

In retrospect, however, their days were numbered.

As Eszterhas wryly notes, the hair of all but the oldest of the male rednecks had by this time spilled well over their ears and was fast heading south. What’s more, by spring of that year, the one issue which more than any other divided the longhairs from the rednecks, the Vietnam War, was officially a lost cause. Other cultural battle lines were blurring as well. Pot and promiscuity were no longer just for hippies, and The Byrds and The Flying Burrito Brothers were proof that country music could be enjoyed by all Americans, regardless of geography, age or hairstyle.

It was up to Nashville Music Row veteran Willie Nelson to kick down the last wall that divided country hippies and rednecks when he took the stage of Austin’s Armadillo International Headquarters, a hippie redoubt, just a few months after the Harrisonville shooting. In an early autobiography, Willie wrote that the “rednecks and hippies who had thought they were natural enemies began mixing without too much bloodshed. They discovered they both liked good music. Pretty soon you saw a long-hair cowboy wearing hippie beads and a bronc rider’s belt buckle, and you were seeing a new type of person. Being a natural leader, I saw which direction this movement was going and threw myself in front of it.” The Red Headed Stranger had accomplished in one performance what the experts had failed to do in years: He had united Middle America.

Today, more than four decades later, when America’s heartland has been hollowed out by meth and heroine and a lack of decent jobs or hope of a decent future, a few Frisbee-tossing hippies seem like a mild problem, indeed. •

Feature image created by Shannon Sands. Other images by Alan Light and Jimmy Emerson, DVM via Flickr (Creative Commons). Last image created by Shannon Sands.