Since the winter of 1995, I have had an ongoing love affair. It has continued even to this day, nearly 21 years later. I have been engaged in this romance, if you will, during the course of several relationships and my marriage. I have always been open and honest about my love for Luciano and I will continue to maintain the open and honest attitude about him in any future relationships.

People change over time. Relationships change and evolve, or end. However, Luciano is the one constant in my life. While my thoughts and ideas about him have changed, I can say the changes are positive ones. That is, as I have matured, the way that I think of him has also matured. As I have spent the years watching him, drinking in every nuance of his movements as he speaks or walks across a room, I have moved beyond a mere infatuation. I have become enamored by him: his presence, his work and humanitarianism, and his care and compassion for others.

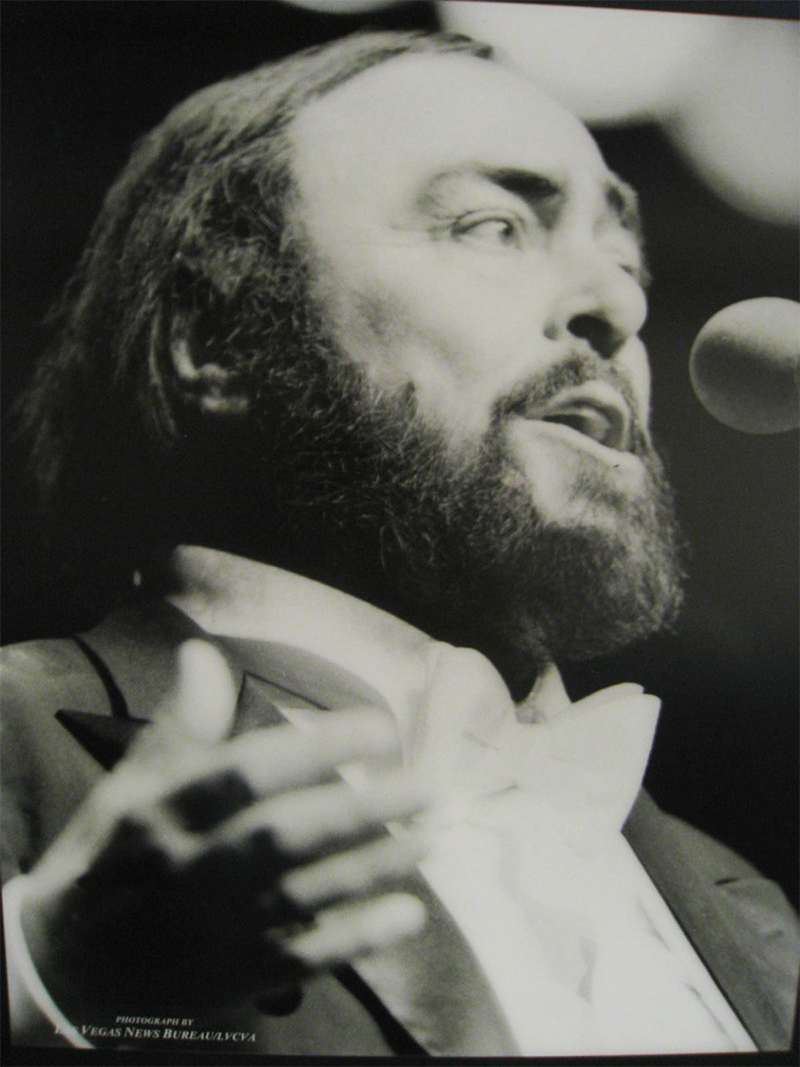

Over the years, I have learned a great deal about the man I met in 1995. In the beginning, I was drawn in by those dark brown Italian eyes. Those eyes revealed a whole range of emotions. I have seen loss, grief, and sadness. I have seen hope, relief, and gratitude glisten. And most importantly, I have seen joy, happiness, and love overflowing in those beautiful brown eyes. I had always heard that the eyes are the windows to the soul, and I never fully understood that meaning until I first gazed upon Luciano. His eyes gave a peek into every emotion he felt before his mouth spoke or sang a single word.

Most people are drawn to Luciano’s “larger than life” image, not his eyes. They are drawn to his fame and fortune, rather than his personality. Of course, I did not have the pleasure of knowing the kind of man he was until much later, but from those eyes, I knew in 1995 that I would experience the wonders of a lifelong relationship with him. Upon that initial introduction, something in me changed. He changed me.

•

Luciano Pavarotti was born October 12, 1935, in Modena, Italy. I was born February 6, 1981, in Athens, Tennessee. Worlds couldn’t be more different. In 1995, I was 14 and he was 42. My first introduction to him was made possible by WTCI Chattanooga — the local PBS station. My first encounter with Pavarotti was thanks to a recording of the 1977 premiere of The Metropolitan Opera Presents. The performance was one that Pavarotti had performed numerous times since 1963: Rodolfo, in Giacomo Puccini’s La Bohème. I never would have imagined that 14-year-old me could be so drawn in by this 42-year-old man, but from the first time I saw him and heard his voice, I was smitten.

On a side note, it sounds like I have a vast knowledge regarding La Bohème and Pavarotti. I do now, but in 1995, I was just a trombonist. To be honest, I had one too many absences in band and in order to be exempt from the semester exam, I had the “opportunity” to write an essay on a “live musical performance” which could actually be a telecast, or a broadcast recorded live performance, which this was. Of course, I procrastinated, and all I could find in the TV Guide was Puccini’s La Bohème. At this point, I did not care in the least bit what type of performance I saw, just as long as I didn’t have to show up to school to take a test. The only problem with this was the fact that I had absolutely no clue as to how to write an essay about music. I had only been in band for two years. I didn’t know anything intelligent about music. Luckily, the Metropolitan Opera sent me Tony Randall.

This was my first proper introduction to the opera, and it is one that I have cherished for more than 20 years. I had seen plays and musicals in my short life, and I had heard orchestras, but I had never seen an opera or even heard anyone sing like that before. The only association I had to opera came in the form of Bugs Bunny cartoons. Now, there is nothing wrong with Bugs Bunny or The Looney Tunes. Fantastic classical pieces of music were brought to a wide audience by the wise-cracking rabbit. Children were introduced to the great composers, like Mozart and Beethoven. They were even introduced to famous conductor, Leopold Stokowski, without being any the wiser. To the kids watching, Bugs was just up to his regular shenanigans. But the opera and music I had known by watching cartoons held no comparison to what I was about to experience in my first viewing of La Bohème.

Tony Randall did his best to explain to me what I was about to experience. First, he explained that the title, La Bohème, meant “the bohemians.” Bohemians were poor, artsy people. Free love. Hippies. He gave the entire synopsis of Act I. He introduced the characters, the problems they faced in the first act, and he even mentioned a love story.

PBS must think its viewers are less than dense. They must have thought the viewer needed some kind of interpreter. I think I needed to learn a little more about opera, then I would have realized how important it was for me to actually pay attention while Tony Randall was speaking. Then, I would have realized that the entire opera was performed in Italian and remembering his synopsis would have been quite helpful. But, I was 14, I knew everything, and I just wanted to write that stupid essay. Thank you, PBS for the subtitles that I didn’t know I would need.

The camera panned away from Randall and settled for a brief moment on the orchestra, conducted by James Levine. The orchestra began to play and the curtains opened.

Didn’t know who that was either. Now I know he is one of the most famous orchestral conductors in the world, and despite his Parkinson’s diagnosis, he still conducts as much as possible for the Metropolitan Opera.

•

In Act I, the audience is first introduced to the poet/writer, Rodolfo, and the painter, Marcello, both dressed heavily in order to stay warm. The two are in the apartment, lamenting their financial burdens, especially that they have no wood for the stove. They begin to discuss how to get a little heat. Marcello plans to sacrifice his painting of the Red Sea, but Rodolfo burns the play he has been writing instead. After all, paper does smell better than paint. As the two are “watching” Rodolfo’s play, Colline the philosopher comes in to warm himself by Rodolfo’s play. Their luck changes when the musician Schaunard comes in. He has brought some money, so now they can at least eat a nice Christmas Eve meal. Their buffoonish landlord, Benoit, comes to collect the rent, but the artists are too smart for him and they trick him into leaving without collecting. Marcello, Schaunard, and Colline wait outside the apartment for Rodolfo to finish writing his article for the paper, so they can all go dine in style together. He said he would only be a minute, since he was in fact “a professional.” Enter Mimì.

The above is (and future synopses will be as well) the “in a nutshell” version. When Mimì enters the apartment, this is where we see how I fell in love with Luciano. This is the important part. Not Rodolfo. Although he was only playing a role, the emotional connection he had with Mimì (Renata Scotto), was not purely acting. He genuinely felt every emotion of the aria he sang. And it showed. Act I is the part of the performance that hooked me on Pavarotti, and opera, for life.

Mimì stumbles into Rodolfo’s apartment. She’s exhausted and seems to be ill. Her candle has blown out, and she simply needs a light. She collapses, and he cares for her. Rodolfo lights her candle from his, and she begins to make her way back to her room. However, she lingers in the hallway looking for her key, and just before he can warn her that the draft will blow out her candle again, it does. Here is where Pavarotti and his Rodolfo steal my heart, along with Scotto’s Mimì. Before she can get back into his apartment, Rodolfo quickly snuffs his candle so they can be together in the moonlight. The look that flashes across his face is playful and full of love. As he and Mimì search for her key in the moonlight, he finds it, and mischief plays across his face as he slips the key in his pocket. Now is his chance; this is the moment he has been waiting for to make his move. As they crawl in the floor searching, his hand finds hers. Be still, my 14-year-old heart.

This is the moment that completely melted my heart. The tenderness. I had heard love songs my entire life, from almost every genre out there. But I had never witnessed such a gut-wrenching, raw, kick you in the stomach moment such as the exchange between Rodolfo and Mimì. His “Che gelida manina” is a tenor staple in advanced voice instruction, as is her “Mi chiamano Mimì” for the serious soprano student.

As Pavarotti sang to his Mimì, professing his love, hitting the higher notes effortlessly and with more conviction than I have ever heard, the tears began to form in my eyes. I had never heard anything so beautiful. The subtitles were a distraction. The music swelled with his voice, his eyes never left hers, and for a moment, every single woman in the concert hall was Mimì. And so was I, from my living room.

The Act concludes with Mimì introducing herself as an embroiderer, and then professing her love to Rodolfo. Their shared duet “O soave faniculla” capped Act I, and while waiting for Act II, I scrambled around for Kleenex. Because I had read enough books and seen enough movies at this point to know that nothing this good would last.

•

In May 1993, I made the decision to be in the seventh-grade band for the upcoming school year. I grew up listening to the radio, and I was exposed to all sorts of genres ranging from the Golden Oldies channels my mother preferred to the Classic Rock stations my father always had on. As I grew up, I found an appreciation for all the different music and artists that flooded the airwaves of those stations and even branched out to artists and genres that were a combination of my parents’ particular tastes. However, I had no clue as to how far those musical branches could actually grow until my first encounter with Luciano.

My Act I as a musician. My choosing to join the band as a seventh-grader contributed to my discovery of opera and, more importantly, Pavarotti. I jam out to some tenor arias. No lie. It’s odd and strange.

Naturally, my parents had reservations about their child joining the school band. Their concerns were more than the typical, “If we get this instrument, will she stick with it?” kind of thing. My mother’s concerns fell more into the “What if other kids make fun of her?” or “Will she ever want to do anything that’s remotely normal?” category. And, looking back on my childhood and my life up to this point, I have always marched to the beat of my own drum, and, honestly, while it might be a lonelier road than some, I have become a stronger person. My father has always understood that. Mom wanted me to fit in and be happy, whereas my father has always just wanted me to be happy with what made me happy. Dad’s voice of reason was why I was able to join the band in the first place.

As a band director now, I can understand their worries. I am lucky enough to see the same worries play across my parents’ faces now. I had never played an instrument or taken an interest in music beyond listening to the radio, and an instrument was not something we just had lying around the house. My mother was concerned about me joining band. There was a social stigma surrounding students involved in band during my parents’ high school days, and in the early ’90s, the stigma was still the same: Band students simply weren’t the cool kids. I realize this line of thinking may seem counter-intuitive now, seeing how music programs really provide students with optimal thinking and reasoning skills as well as a lifelong activity, but those perks of a musical education had not fully been researched at the time. So I can understand her concerns. She was worried. Her loner child was wishing to pursue yet another activity (the chess team came first) that went against her idea of the social norm of the typical 12-year-old girl. My father, however, was less concerned. Since I had never been acquainted with playing an instrument other than the recorder, he felt it was just a phase. He even comforted my mother by saying, “Let her join the band; it’s just a phase.”

The summer of 1993 passed slowly. I was excited and terrified about joining band. All the anxiety and insecurities that I normally felt seemed to magnify. What if I couldn’t play an instrument? What if I was really bad at it? What instrument would I play? The thought never even crossed my mind of whether or not I would enjoy playing an instrument or being part of the school band. Of course, my mother’s fears began to creep into my mind. What if the other students at my new school didn’t like me or what if they made fun of me for being in the band? Those are big, real fears for a 12-year-old.

August 1993. New school. New activities. I walked into the round school for the very first time, and all my fears about band were replaced by fears of getting lost. I had never been in a round school before. Even with the different subject and pod areas color-coded by blue, red, yellow, and green lockers, I still couldn’t find the bathrooms, let alone the band room. I had never been so lost or confused. I had gone from having one teacher in the same classroom to having seven different teachers in seven different classrooms. As the first day came to a close, it was apparent that junior high was going to be the death of me. Then I walked into my band class.

As I walked into the room, I saw the band director who had spoken to us as sixth graders just a few months before. She knew exactly who we were before she ever formally met us. To this day, I still have no idea how she did that, unless she snagged a couple of yearbooks from the elementary schools. She was the only teacher I had the entire day that already knew her kids. That was comforting. And as we all found our seats, she started to tell us all about the different instrument and even demonstrated how they all sounded. To a kid who had only played the recorder, and not very well, it was amazing. How could one person know how to play so many different instruments and make them all sound how they are supposed to sound?

At this point, I was enthralled. By the end of the class, I knew I would play a brass instrument. Those seemed the most durable. The flute and clarinet looked so fragile, and to a 12-year-old, they had a million keys, as did the saxophone, and I only had ten fingers. The only things left were percussion or brass instruments. If I chose percussion, I would have to be able to play different kinds of drums and other assorted auxiliary instruments such as triangle, guiro, tambourine, bells, cymbals (including crash and suspended), etc. Once she named what seemed like a thousand percussion instruments, she moved to the brass family. These seemed much more plausible. There were only four of them, and only two of them were allowed for beginners: trumpet and trombone. To the uneducated future musician, the trumpet had three “buttons” and the trombone didn’t have any. The trumpet sounded regal and majestic, but the trombone had a unique quality. A slide. Slides are fun, right? The sound of the trombone was also very different, and due to the lack of valves, a trombonist could make a whole host of different sounds. The sound wasn’t majestic, but it could be. It wasn’t a pretty sound either, but it could be. I could hear and see so much potential in this strange-looking instrument. I’m sure we see where this is going.

The first day may have seemed hellish, but the first day of band changed all of that. There was something that could distinctly set me apart from the rest of my family, and unlike many of my classmates, I knew exactly what I wanted to play, and I could not wait to tell my parents. Of course, my mother hoped I would pick the flute or the saxophone. A trumpet would have even been a fine choice. Of course, as a 12-year-old, my mission in life was to be different and to give my mother headaches. Naturally, my interest gravitated toward the trombone. It was different. Like me. Mom voiced her concerns, and dad being dad just responded, “Let her play the trombone; it’s just a phase.”

Some phase, huh, dad? 23 years and counting . . .

•

Tony Randall came back to make sure I was emotionally stable enough to continue on to Act II. He told me Act II was happy and funny. It was Christmas Eve, after all. It was a magical time. The bohemians were shopping, spending time with each other, rekindling romances. All was right in the streets of Paris.

Remember, sung in Italian . . . no wonder I was so confused. French name. French setting. Italian libretto.

There were no tears on my part at the moment. Maybe I was wrong about this love story.

Tony Randall was back, and he had crushed my dreams.

Act III. February has come. Rodolfo and Mimì have split. She has grown sicker. Rodolfo can’t keep her warm enough to keep her well. He claims he is jealous (and she believes it) of how she carries herself around other men, when in reality, he really wants her to find someone who can provide for her. The pain in his eyes says everything. He loves her. And she loves him, but she is dying. And he knows it.

Tears.

The orchestra plays themes from Act I as Rodolfo comes outside. Mimì is hiding, eavesdropping on his conversation with Marcello. Rodolfo admits to loving her. Then he hears her cough.

Tears.

He goes to her, and they agree to stay together until spring. They hope winter lasts forever. Especially Mimì. Spring will bring her death. She grows weaker by the day.

Tears. Tears. Tears.

•

January 1996.

My Acts II and III.

I noticed something absolutely wonderful about the trombone in relation to the Italian tenor. When a trombone was played well, as it was by my private instructor, it sounded like the human voice. Even in all the fun sounds a trombone could make, it could be just as beautiful as the voice of an Italian tenor. One day, I mentioned to my instructor what I thought about the trombone, and the next thing I knew, he handed me a method book, The Singing Approach to the Trombone. This is a text I have come back to time and time again. Charles Vernon’s theory to teaching and playing the trombone is really the same as a vocal student. Hear the sounds as if you are singing.

Maybe not as if “I” were singing. There is a reason why I joined the band. Singing was not, and is still not, my forte.

The exercises in the book all mimic the vocal warm-ups found in choir rooms. Pitch changes should be smooth, yet articulate. As I read and worked through the exercises, the sound I always imagined was Pavarotti. To me, the “greatest trombone sound in the world” was more along the lines of an Italian tenor, and he was my tenor of choice. Even now, 20 years after beginning to study this method, I use it with every note I play.

They do say imitation is the sincerest form of flattery. I may never reach my goal of sounding like Pavarotti. But I know I can always listen and try. He brings me peace.

As the years have worn on, my practice time and performance schedules have dwindled. I teach more than anything. Life has happened quite frequently, and sometimes I leave Luciano for a while. I always come back, and he is always there. His arias always pull more from me when I think I have nothing left to give.

•

Tony Randall came back for a final time.

Act IV. We are back inside the apartment with Rodolfo and Marcello. The orchestra sounds playful as Rodolfo and Marcello work. Or at least try to work. Their concentration has been broken, like their hearts. They lament over their loves instead of the heat. Mimì and Rodolfo have split again. This time it is over. Randall drones on. He reveales Mimì’s fate. Her tuberculosis has gotten worse.

At least it’s spring. Schaunard and Colline come into the apartment, just like in Act I. They have brought more treasures home. Food. Money. So far, the opera is ending just as it started. The music has not indicated anything

is any different. The sounds from the orchestra continue to be playful. Then, Mimì is brought inside. The mood instantly changes. They profess their love to one another again, for the final time.

Tears.

The bohemians scavenge to find things to sell to buy medicine for her.

Tears.

They are too late. And of course, this needs to be as tragic as possible, so she dies in Rodolfo’s arms. Mimì lies on her deathbed, singing the most beautiful, heartbreaking aria and duet with Rodolfo, “Sono andati?” Rodolfo gives Mimì the bonnet he had bought her in Act II, and for a moment, I truly believed she would live. I have never seen such pain portrayed by actors. Genuine pain. As they embrace for the last time, the orchestra swells into Rodolfo’s aria from Act I.

Inconsolable.

•

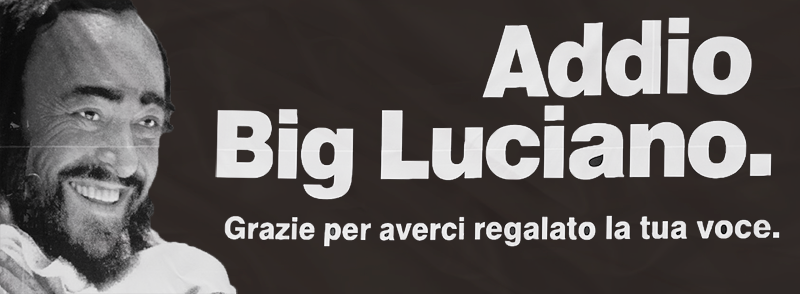

September 6, 2007.

His Act IV.

It was a Thursday. As I prepared to go to work, I flipped on the news. Luciano Pavarotti had died from pancreatic cancer. He would never finish his farewell tour. He would never really retire. For me, this was the day the music died. My entire day’s lessons were changed en route to work. During that particular semester, I was teaching the history of jazz and 20th-century popular music. Not classical or opera. But on that day, I taught, and have continued to teach every September sixth, opera and Luciano Pavarotti.

Over the years, I did have a wonderful opportunity to learn more of Luciano Pavarotti. He was more than an opera star. He was seen as a rock star, even by rock stars. He loved music. And he loved children. So he did what he loved, for whom he loved. From 1992 to 2000, he organized multiple concerts in his hometown of Modena to raise money for children hurt by war and other circumstances. Not only did he sing with other opera stars, but he sang with artists like Bono, Brian May, Eric Clapton, Bryan Adams, Celine Dion, the Eurythmics, and the list goes on and on. They performed opera with him, and he performed their songs with them. He loved making people smile, and he loved working with other artists. He really was larger than life.

Although he is gone, his performances and charity work have been immortalized. There will never be any new recordings, but he will always remain a constant for me. The 1977 production of La Bohème will always hold a special place in my heart. That performance molded me as a musician, first and foremost. I understood in two hours more about musicality than I have learned in 23 years. Music, especially opera, speaks to the soul. There is something resonant that cannot be labeled. Long after the performance end, the emotional impact stays with an audience. I want to be a part of the musical resonance. And for as long as I am able to play, I will continue trying to reach people the same way he reached me through music. And with each breath I use to play my instrument, I can strive to sound more and more like him, especially when reaching for the high Cs he so effortlessly sang.

I never would have imagined that a “phase” would have brought me to this point of musicianship in my life. I am fortunate to have parents who allowed me to be strange, and odd, and who encouraged me to do the different things in life, so I could find my thing. I know they would prefer to not hear opera at night when trying to sleep, but they understood what it meant to me. Opera and music turned out to be my thing. •

Feature image created by Shannon Sands. Photo of Pavarotti courtesy of Dan Perry via Flickr (Creative Commons). Goodbye Luciano banner referenced from Stefano Mortellaro via Flickr (Creative Commons). Other images created by Shannon Sands.