A few months ago, I decided to take a sentimental stroll through my old uptown neighborhood in New York City. It was about four in the afternoon that late autumn day when I exited the subway station at 145th and Broadway. Since it was cold, I wore a heavy leather coat, a black turtleneck with matching jeans, and black Timberland boots. Besides the McDonald’s on the corner, the one Jay-Z refers to on “Empire State of Mind,” little remains from those years when I was just another shortie growing-up along the way.

After years of neglect due to drugs, it was nice seeing new shops, restaurants, and clothing stores opening, but, at the same time, it was depressing to peep through the window of one bar/restaurant and see no faces of color except for the dishwasher. Walking down the avenue, I stared at the unfamiliar storefronts that used to be something else, as well as the newly built structures that will one day serve as landmarks in the memories of the new kids when they are middle-aged and obsessed with the way things used to be.

These days, the realtors call that community Hamilton Heights, but growing up back in the 1970s, we always considered it just another part of Harlem. Like most of Manhattan in the last 20 years, things have changed considerably since those long-gone days when I was a child and those asphalt sidewalks were my entire world. Back then, it was a mostly a working-class community of lower-income Blacks and Latinos. There were also more than a few Asian, Italian, and Jewish families in the neighborhood; indeed, we were that “melting pot” that people used to talk about years before “diversity” became a common cliché.

Six blocks from the subway stop, I stood on the corner of 151st Street and Broadway my old block, and watched as many faces passed by — but recognized none. It was on that spot where my former crew used to chill in the summer with our massive radios, blaring soul/disco songs (WWRL-AM or homemade cassette tapes) while up the block Latino men dressed in Guayabera shirts and sharp slacks played congas and bongos until dusk, slapping the drums’ skins with gusto as their bodies vibrated rhythmically.

Once upon a time, there were many musicians, actors, singers, dancers and painters living in the area. Walking down the street one might’ve seen Nipsey Russell hailing a taxi, Diahann Carroll shooting a movie (scenes from her 1974 Oscar-nominated role in Claudine were shot on my block), original Saturday Night Live cast member Garrett Morris in the supermarket, jazz guitarist Jean-Paul Bourelly in the subway station, or veteran Gone with the Wind actress Butterfly McQueen on the number five bus.

The neighborhood had also once been the home of leading literary figures including author Richard Wright, who dwelled at the Douglass Hotel on 150th and St. Nicolas when he relocated to Harlem in 1937 while working on his landmark novel Native Son. 15 years later, novelist Ralph Ellison, who was 39, and his wife Fanny moved down the block from there to the Beaumont Apartments at 730 Riverside Drive the same year his classic novel Invisible Man was published; he lived there until he died in 1994. Today, across the street from his old building, there is a bronze and granite Elisabeth Catlett sculpture that serves as a tribute to both the man and his renowned book.

When celebrated poet and feminist writer Audre Lorde was a little girl in 1945, she moved to 152nd and Amsterdam with her family. According to the 2006 biography Warrior Poet, beautifully written by Alexis De Veaux, the Lordes were the first Black family on the block. “A week after they moved in, the landlord of the building committed suicide, despondent over the fact that he’d been forced to rent to colored people,” she wrote. Another beloved writer, Toni Cade Bambara, whose short story collection Gorilla, My Love helped guide me through my own urban fiction writing beginnings, grew-up a block away on 151st between Broadway and Amsterdam in the 1940s and ‘50s.

Bambara incorporated the neighborhood (including The Dorset Theater, which during my childhood became the Tapia) into her work, including that collection’s title story and the much-anthologized short “Raymond’s Run.” Attending the prestigious academy the Modern School, a bougie, Black, private grammar school where she felt, as I did when I went there 20 years after, out of her place. According to the biography A Joyous Revolt: Toni Cade Bambara, Writer and Activist by Linda Janet Holmes, the acclaimed author couldn’t relate to the other students. “They were Black people, but they were not my people,” she once said.

Standing on the corner, I stared down the hill at the wave-splashing beauty of the Hudson River, its splendor often taken for granted by the locals. Observing the water as the sun began to set, I remembered the many winters when the river was frozen solid and it looked as though I could walk down to Riverside Drive and slide across the ice until I reached New Jersey. A few minutes later, I headed down the hill towards my old building.

Many uptown buildings have names etched above the front doorways by developers or architects, and ours was called the Rivercliff. Built in 1914, its vast courtyard separated the street from the front door. Periodically, I liked to go see where I was raised, that place where I wrote my first stories. I’d stand in that grand courtyard, head held back as I looked upwards at the six-story building that was as familiar to me as an old song.

Touching the building’s bricks, I waited for ghostly voices to whisper in my ear and flood my mind with dusty yesteryear memories. There were gargoyles carved into the building, peering down from overhead. Although I was four when I moved in, it wasn’t until I was eight that I first noticed the gargoyles, as my visiting cousin Harold pointed upwards and screamed, “Oh wow, what’s that?!” Luckily mom was there too, and when she finally figured out what he was talking about, she replied, “Those are called gargoyles. They were put there to protect the building from evil spirits.” Harold and I, confused children that we were, both made funny faces.

The year before, I had walked through that courtyard and looked through the glass and steel front door into the lobby; it had changed a lot since I last lived there in 1992. Dangling from the ceiling was a sparkling chandelier, an ugly table with a large, fern-filled vase was in the middle of the lobby, and gilded mirrors on the marble wall. The lobby was obviously supposed to be fancy, but instead looked like a tacky singles bar. Later, when I looked at the landlord’s website, none of the beautiful young models walking across the lobby resembled any of the former working-class residents that once called that building home.

Conceived, born, and raised in Harlem, I’ve grown used to how quickly it could change, but nothing prepared for the sprawling black gate that had been built in front of the courtyard since my last visit. The gate was large and intimating, making it impossible to step into the courtyard without a key. I stood in front as a loud voice in my head screamed, “What the hell?” Peering inside, I felt like the man in the Kafka parable “Before the Law,” who stood in front of a similar blockage his entire life, hoping he’d be allowed to inside; instead, he died trying.

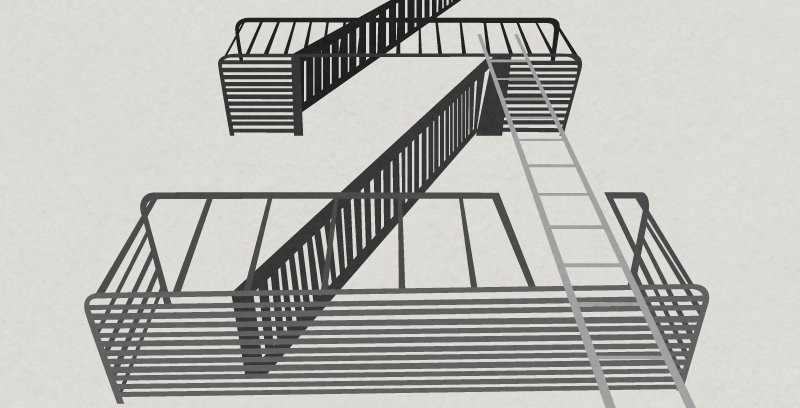

With fire escapes scaling the building like something out of a noir film, this was my ground zero, my motherland, where it all began with me and baby brother and all our friends who were more than friends. Having moved into the pre-war dwelling with its 64 units in 1967 with mom, grandma, and baby brother when I was four, we lived on the first floor in apartment 1-E. Back when we were kids, that courtyard was more than a courtyard: It was our community center, and it was open to whomever wanted to play there after school or on hot summer days, where we did our thing until the ice cream truck came.

Painted bright red, the color it remained throughout my childhood, the courtyard was where me, baby brother, and all our friends (Kyle, Beedie, Jackie, Darryl, and Sylvia) played various New York City games (ringolevio, skellies, red light/green light, and tag); it was in that courtyard that the girls played jacks or jumped Double-Dutch while the bros were usually involved in an intense game of Booties Up with a pink Spalding high-bounce ball or trading baseball cards.

Light-skinned Miss Josephine, the mother of my homeboy Kyle, sat in the same spot next to the wall at the entrance of the courtyard. While today there is a sign that warns “No Loitering,” back then that was Miss Josephine’s spot where on nice days she sat, exchanging gossip with our neighbors, talking to Miss Johnnie Mae, who had a sweet southern accent, or waiting for the last number to come out and for Mr. Peele to come down the hill complaining he’s missed the damn thing by one figure.

Miss Josephine was like the “big mama” of our building, and she was also close friends with my grandmother; it wasn’t uncommon for the two women to stand in the courtyard talking about everything from trifling kids to fried chicken recipes to the lady on the second floor who left her husband for the lesbian from Philadelphia that lived on four. “Miss Josephine is like the newspaper,” I said to my mother one day, “she knows everything that’s going on.”

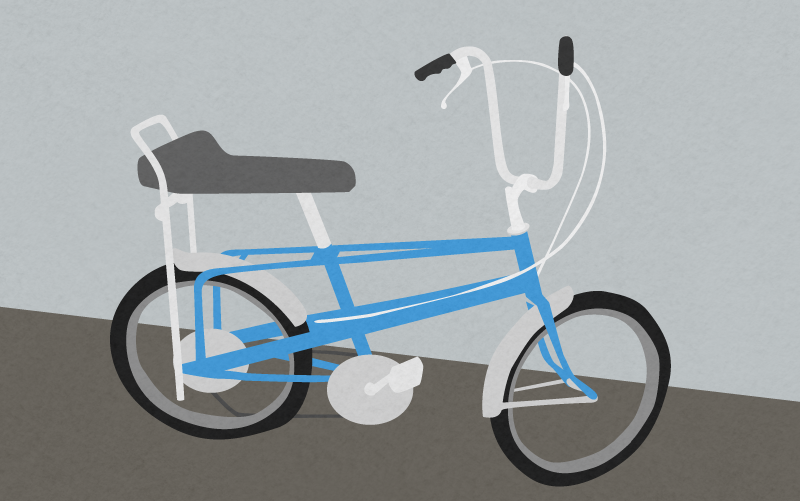

It was in that courtyard that I practiced riding my second bicycle, a cool blue Ross-Apollo five-speed that my stepbrother Brian gave me. It was in that courtyard that I was introduced to rap music, sitting in awe in the summer of ’77, watching DJ Hollywood plug his system into the streetlamp and spin records at our annual block party as Lovebug Starski rocked the mic. A week later, I sat in precisely the same spot when the street lamps started flickering and the blackout of ’77 went into effect. While the stores on Broadway were being broken into by looters (loud screams, breaking glass), I remained in the courtyard with my 628 family, safe from harm.

By the late 1970s, many of the families at 628 began moving away: the first was Darryl and Jackie Lawson, whose house we played in often, and then our boy Beedie broke out, and then Marvin and his family were also gone. In ’78, mom moved me and baby brother to Baltimore, but grandma stayed. After graduating high school in 1981, I returned to the city, happy as hell to be coming back to that beloved building.

However, when the cold winds of crack cocaine blew through the neighborhood three years later, the community began to crumble as the cops at the 30th precinct, who were later discovered to be corrupt and working with the drug dealers (the newspapers called them “The Dirty 30”), did nothing. Dudes I’d grown-up with began selling coke and crack openly while other friends of both sexes became “fiends” of the highly additive drug. At night, we prayed that a random bullet wouldn’t shatter the window and accidentally kill us.

“It’s like the wild west out there,” Grandma said one night as the sound of gunfire erupted outside our window. “It used to be so nice around here.” During the decade of devastation that followed, long-time residents fled and many properties were abandoned. At nightfall, prostitutes gathered in doorways, performing oral sex in the shadows. Numerous landlords, including our own, were no longer making building repairs, instead allowing their properties to rot.

For two years, I watched the hole in our bathroom ceiling get bigger and bigger while the building superintendent did nothing. In 1991, when the rusty pipes were fully exposed and water leaked constantly, I moved to midtown Manhattan with my girlfriend Lesley. Grandma headed to Baltimore the following year.

Slowly, as the decade moved forward, the crack epidemic finally faded from the landscape. My one-time hood struggled, trying hard to come back from the damage of drugs and decay. It was a slow process, but soon the gunfire became infrequent and the neighborhood felt less dangerous. However, even at its most bleak, I always returned to my old hood, my old block, my old friends, and my old courtyard.

25 years after I moved from that building, I stood at that imposing gate as darkness began to fall. Looking at that massive structure, I knew in my soul that would be my last visit to my building. Seconds later, I figured I should get moving before one of the new residents called the police to report a strange Black man loitering on the premises. If I knew how to cry, perhaps I would have shed a few tears, but instead I stood silently, staring into the darkness beyond the gate as a brisk wind blew.

Turning around to leave, I was surprised when I saw my old friend Kevin Woods standing on the stoop across the street. After many battles with many landlords, he’d managed to hold on to the rent-controlled apartment where he’d lived since we were kids. “What’s up, homeboy?”, Kevin asked, slapping me five.

“Don’t call me that,” I replied, glancing across the street at the gate. “This isn’t my home anymore.” •

Feature image provided by Sandra Lee Jamison. Other images created by Shannon Sands.