I am in Cuba, sitting in a bar with Ernest “Papa” Hemingway. The Floridita, made famous for its daiquiris, has capitalized on the writer, installing a life-sized bronze statue in the corner where he would sit and order “papa dobles.” In his time, Hemingway enjoyed drinking here with fishermen, sailors, and regulars. Now, it’s a tourist trap. The air is thick with overpriced cigars, the bar is inaudibly loud, and the room is crowded by foreigners attracted by the writer’s renown. The only Cubans are the ones working. A man in a fanny pack next to me says to a younger woman, “Hemingway is great,” as he creeps closer to her through the mob. “The Great Gatsby was one of my favorite books in high school.” I leave the bar, disappointed and bitter.

The first time I read anything by Hemingway I was 16. I picked up For Whom the Bell Tolls after recognizing the title from a Metallica song. Before, my reading catalog consisted mostly of sci-fi and fantasy, which allowed me to indulge in daydreams of other worlds. For Whom the Bell Tolls was the first work of “literary fiction” to truly stir me. I felt a connection to Robert Jordan, in his search for meaning in the Spanish Civil War. A young man, caught in the conflicted ideals of romance and revolution, fighting but never quite certain of why. Impressionable and feeling lost, the novel sparked in me a desire; a greater purpose and a passion for adventure, one that could be found in this world. Years later in college, I studied political violence and revolutionary theory, an interest I trace back to the dynamited bridge.

“My mojito in La Bodeguita, my daiquiri in El Floridita.” Outside the Bodeguita del Medio, the scene is just as ugly as the Floridita. The crowd has gathered on the street, and people shove one another to get inside. The bar itself is tiny. A bartender mass-produces the rum-and-mint drinks, while another tries desperately to manage the flow of orders. Hemingway adorns the walls in dozens of photos. A plaque out front commemorates the poet Nicolás Guillén for his contributions to this bohemian sanctuary-turned-money-maker. Cuba has no shortage of its own literary titans, and down the street is the mansion that inspired Alejo Carpentier’s El Siglo de las Luces (in English: Explosion in a Cathedral). But this attracts little attention. Cuba’s writers are overshadowed by the legend of Hemingway. On the walls in and around the bar, travelers have graffitied their names. I scratch my signature before crossing Old Havana to take refuge at the Dos Hermanos.

While I respected his work, it wasn’t until I read The Sun Also Rises that I came to idolize Hemingway. After graduating from college, feeling conflicted on my future, I took a gap year to sort things out. After four years of studies, I had become bored with theories, and the practice of politics seemed hollow, given my discontent with America’s elected officials. Seeking to better understand what I wanted, I lost myself in Southeast Asia. I spent several months living and working in Thailand as an English teacher, with marked sojourns across the region. As a young traveler, I took with me the essential travel book. For most of the novel, I was unimpressed. The characters seemed flat, and even Jake appeared to be a very surface-level protagonist. It was somewhere near the end of the second act that the narrative clicked, and suddenly I saw the hidden depths of each personality. I came to appreciate The Sun Also Rises as a work of genius.

Written when he was 27, The Sun Also Rises was the book in which Hemingway perfected his iceberg technique. The method relies on minimal development and allowing the reader to discover the characters slowly; this delayed gratification is what makes the story satisfying. This had a monumental impact on me and taught me that beyond the story, even the writing of a book could be crafted as an art. I realized then something I had always known but never quite had the courage to pursue: I wanted to be a writer.

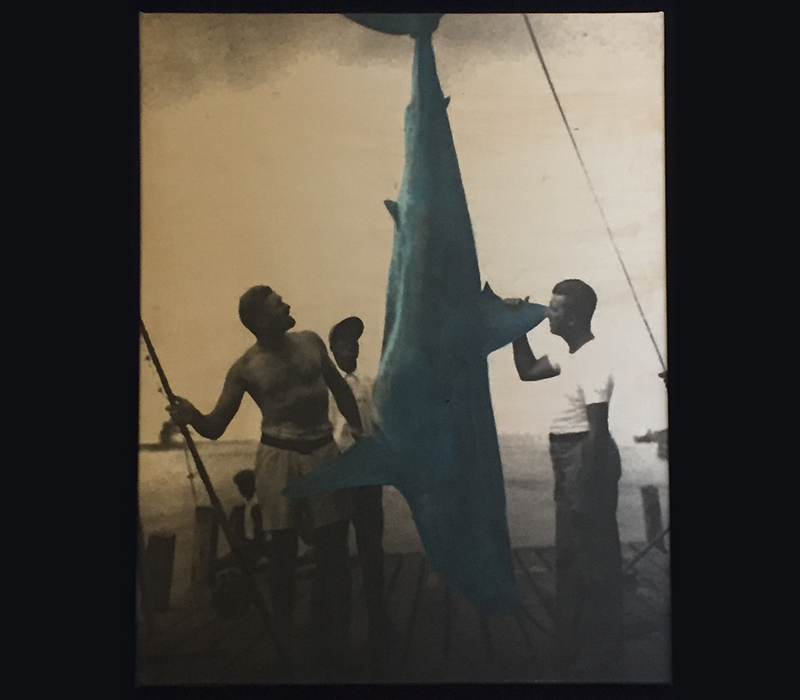

I walk through the lobby of the Ambos Mundos Hotel, whose name means Both Worlds. The walls are decorated with photos of its most famous guest. As I climb the stairs to the fifth floor, each landing has a portrait of the man of action: here he is on an African safari, dressed in khakis, shotgun in hand, before him the carcass of a lion; here he is gazing up at a shark, shirtless with fishing rod, the predatory fish hanging by its tail. The images are sepia tone, with the dead animals colorized. I arrive at room 511. I attempt to enter, but it is locked. A woman’s voice from the other side tells me it costs $3 CUC to enter and to wait. I wait. Several tourists turn up behind me, to my displeasure. The door opens, people flood out, and we flood in.

The woman, a sharply dressed attendant, gives us a lecture on the room. It is supposedly well-preserved from the days in which Hemingway was a semi-permanent resident of the hotel. I am skeptical. The suite is small and sparsely furnished. There is a cabinet filled with a collection of books, the complete oeuvre of his literary works. On top the chattel there are ornaments and memorabilia. A model version of his boat El Pilar, a bust of Hemingway’s head, a caricature drawing. One wall has a series of newspaper clippings from around the world, declaring Papa the winner of the Nobel Prize in Literature, awarded in 1954. In the corner is a king-sized bed, above which is a picture of Fidel Castro and the author from a fishing tournament the latter hosted in Cuba. The center of the room is occupied by a timeworn typewriter, enclosed in glass, on an adjustable height desk; due to a knee-injury sustained in the first word war, Hemingway did much of his writing standing up. In this space, he wrote three books, among them, Death in the Afternoon.

After five minutes we are shuffled out, and new visitors shuffle in.

Much of my admiration for Hemingway comes not just from his style, but for the thematic elements his writing touches upon. War and revolution, love and loss, adventure and romance of the unknown. Most of his protagonists fit the mold of the quintessential “man:” strong, stoic, discreet, daring, respectful, and self-contained. Men of action and endeavor. This concept of manliness has fallen out of fashion, now labeled by some to be examples of “toxic masculinity.” The modern man is encouraged now to be more open and expressive with his emotions, more sensitive and caring, to resemble more of what traditionally might be associated with feminine characteristics.

My own perception of what makes a man was shaped by my father. (Who, as coincidence would have it, bears an uncanny resemblance to Papa Hemingway.) Broad-shouldered and muscular, resolute, decisive, and valiant without false machismo, my father has lived a life of action. His career has seen him play the roles of police officer, firefighter, and soldier; he has been in shootouts with criminals, rushed into a building’s inferno, aided in the rescue and restoration of Ground Zero, and fought in the first Gulf War, Desert Storm. Like Hemingway, my father’s father died while he was young. Papa’s by suicide; my father’s by heart attack. Neither liked to talk much about it.

While his legacy is sustained by his novels, I am of the opinion some of the author’s best work is in his short stories. I have read the anthology The Short Stories of Ernest Hemingway, as well as several of the original compilations. Among my favorites: “A Way You’ll Never Be,” an insight into the mind of a man who has seen true death and the carnage of war; “Now I Lay Me,” on insomnia and the things that keep a man up at night; and“Big Two-Hearted River,” one of the Nick Adams tales, an account of finding peace in the simple matters of life.

I have been privileged in life, in that most of the violence I have known has come from the stories of others, men like my father and Papa. At times, it bothers me that others chastise those who take solace from what they’ve experienced in the form of stoicism.

I arrive at Finca Vigía, Hemingway’s house on the outskirts of Havana. In this home, he wrote several novels. Among them, For Whom the Bell Tolls, A Moveable Feast, and Islands in the Stream, which I have been reading during my journey around the island. I arrive as early as possible, on the chance it will be empty. I know that it will not be.

There are a few people here, but the home is large, and it creates the illusion of privacy. The inside is barred to visitors, and so I circle the house and peer through the windows. Papa’s study contains a large mahogany desk, rows of bookshelves, and a large poster of bullfighting in San Sebastian. His bedroom has more books and a newspaper on the bed. The living room has two floral sofas, a liquor cabinet, bottles, and a coffee table with an ashtray. Every room is mounted with trophy heads: deer, elk, bull, ox, bear. I wonder if there was ever a lion.

Tour groups begin to arrive. Although I feel dismissive, I find myself eavesdropping. One guide tells some Germans that Mary chose all the furniture, another tells four Brits of how Hemingway invited the cast of The Old Man and the Sea back to his casa to drink after filming. I wander the grounds. In the back is a ring that once held cockfights, an empty pool, a small cemetery for pets, and El Pilar Papa’s prized boat. When he died, Mary wanted to sink it off the coast of Cuba, but the Castro government forbade it. They compromised, turning Finca Vigía into the museum it is today. Later, Hunter S. Thompson visited the house where Hemingway died and stole a pair of antlers. I think about taking a book from Hemingway’s library and consider bribing a guard.

Behind the home is a watchtower. I climb the stairs to see it. At the top are a telescope, a typewriter, a lounge chair, and more books. Due to his knee, the man did not ascend the tower often. However, I imagine when he did, he must have really loved it. You see across Cuba to Havana, the rolling greens, and the jutted landscape. The view is quite beautiful.

In 1960, shortly after the revolution, Hemingway left Cuba for Ketchum, Idaho. In 1961, he took his shotgun, put it to his head, and pulled the trigger. Reports are conflicting as to why.

After I left the casa de Papa, my driver asked if I wanted to see Cojimar, the small village where The Old Man & the Sea is set. I told him no. I knew what I would see there: the restaurant La Terrazza, in which Hemingway once drank with Cuban fisherman but now where they would be a plaque or a statue or a bust of Ernest, with too many tourists, and the driver would charge me three times what it should cost for the ride.

The reason I came to Cuba was not simply to take the tourist trail but to put myself to a test. Although, I’m not sure if I passed. I wanted to see if I could write, really write, as a journalist. I have written several articles, and when I return to the States, I intend to pitch them to as many papers as I can. My experience thus far is that they won’t even be rejected, just ignored. The field of journalism has changed drastically in the 80-some years since Papa learned the style of short, declarative sentences. These days, with the advent of the internet, it is cheaper for journals to use freelancers, meaning that there is more competition. And worse pay. Would Hemingway have been dissuaded?

The best way to get paid to write is to make a name for yourself. But how do you make a name? I have thought about just buying a ticket to Syria and throwing myself into the action. I have spent years studying the Middle East, and I’m certain of my qualifications. However, I’m held back by the reasonable fear of being kidnapped or beheaded. There is also, as always, the matter of money. Thanks to my pursuit of knowledge, I am currently in six figures of debt with a seven percent interest rate. I skipped the gradual and went straight for the suddenly broke. Would Hemingway have been demoralized by student loans and fear?

I know my affinity for Hemingway makes me unjustly jealous when others crowd my time with him and his legacy. There is an intimacy between writer and reader beyond words. This is particularly true in the case of Papa, whose frequent use of roman à clef gives his work greater gravity. I am possessive of the man, even though I know I have little right to be.

Ernest Hemingway was a man of the world, and he belongs to all of it; to Spain and France, to Africa and America, and especially to Cuba, to whom he dedicated his Nobel Prize. As for me, I’m not sure of the future. I hope only to stand on the shoulder of the giant, so that I may see a little farther.

In the words of the writer, “A man can be destroyed, but not defeated.” •

Feature image courtesy of Franck Vervial via Flickr (Creative Commons). Other images provided by the author.