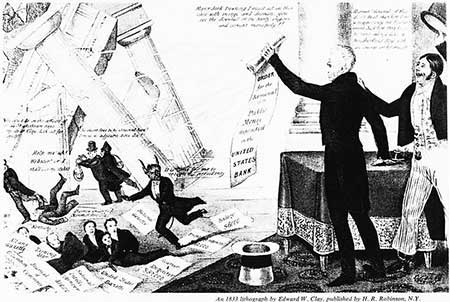

In one of the most famous political cartoons of the 1830s, President Andrew Jackson stands in the pose of a triumphant Roman emperor below the soaring Roman columns of his mansion, the Hermitage. He unfurls a decree, indicating his order to withdraw U.S. Treasury funds from the Bank of the United States (B.U.S.), the nation’s central bank. Jupiter’s thunderbolts emanating from the scroll zap the Greek Doric columns of the Bank, knocking it and the Bank’s president Nicholas Biddle, a noted Grecophile, to the ground.

The politician Charles Ingersoll likened Biddle’s fate at the hands of Jackson to Acteon, an unwitting victim of Greek mythology, ripped apart by “dogs” who, in better days for the Bank, “licked his hands and fawned on his footsteps.” In other cartoons during the period of the Bank War, as the fight over the political and economic role of the central bank came to be called, the tables were turned (indeed as they were for Acteon), and Biddle was depicted as the hero. In these, notes architecture historian Michele Taillon Taylor, “Jackson, the reckless Roman, confronts Biddle, the steadfast Greek: vice squares off with virtue.”

These weren’t vague allusions. Americans, says Roger Kennedy, the late former director of the Smithsonian’s Museum of American History, “were coming to be — indeed, insisted upon being — themselves, neither effete Europeans nor savages.” The classical world with its democratic connotations and civic traditions would be their template for a third way, made real through architecture and political ideology. But the appropriation of the classical world broke down along party lines. Jacksonians, Kennedy says, built their houses in Roman style, while Federalist and Whig supporters of Biddle became the chief advocates for the emergent Greek Revival.

The Bank War only deepened the ideological divide, forging political lines we can’t quite escape today. Biddle, an urban elite with civic vision, took over the B.U.S. in 1823 at age 37. He was a chief advocate of the “American System” of national development, a modernist platform that included a strong central bank and a national paper money currency at the heart of a unified financial system, the establishment of institutes for science and technology, the building of canals, roads, bridges, and railroads, and free public education for everyone. Biddle’s education blueprint made use of polytechnic institutes and colleges. Universal education, he thought, would protect liberty. “Our general equality of rights would be unavailing without the intelligence to understand and defend them,” he said.

Jackson’s “true Democrats” on the other hand, certain in their belief in a yeoman economy, localism, state’s rights, and hard money distributed by unregulated private and state banks, saw Biddle’s system as imperialism, and they pushed back with rhetoric that has endured to present-day fights over gun control and Obamacare.

As the struggle over America’s third way built toward the Bank War, some 4,000 miles away, in a Papal-controlled village northeast of Rome, a hunchback named Giacomo Leopardi pursued his own third way, beyond the repressive life of the traditional village and the horrors of the modern world. Like his American contemporaries, Leopardi too sought his salvation in the lessons of the ancients, says Franco D’Intino, one of the editors of the first English edition of Leopardi’s 1820-1830 diary, the 2,500 page Zibaldone, put out this fall by FSG, a work that Tim Parks of the New York Review of Books says is “considered the greatest intellectual diary of Italian literature.” For Leopardi, ancient Greece and certainly not the more tyrannical and systematized ancient Rome, represented an idealized state of humankind, particularly for its relationship to nature and the potency of its illusions.

I spent much of November reading the Zibaldone (which translates loosely as miscellany); the translation is both lush and firm and, given the range of languages Leopardi employs, is itself one the great literary endeavors of our time. Often, while reading, I would find myself thinking about American politics, particularly the regular rhetorical convulsions about federalism and states’ rights, localism and uniformity, systems and the individual, and government power and personal responsibility that framed the Bank War and infects discourse today. The Zibaldone, indeed, put these lines of ideology in a new light, even as Leopardi gives barely a thought to the American experience as a potential setting for the revival of primordial ways. Notably, Leopardi’s compelling vision, situated as it is in ancient Greece, matches the Jacksonian ideal far more neatly than that of Jackson’s Grecophile enemy Nicholas Biddle.

Not at all unlike Jackson, Leopardi finds modernity fundamentally bankrupt, for it deals in abstraction instead of face-to-face reality (and reality’s cousin illusion), and its language of reason corrupting of human experience. Reason, says Leopardi, distances us from nature and instinct, the only true teachers of mankind, and abstraction leads to tyranny. “We have no choice in this pitiful century of reason and enlightenment,” he wrote in one of the earliest entries, in 1820,

but to flee from ourselves and see how the ancients, who were still children, spoke, and how they saw and depicted the sanctity of nature with eyes that were neither malicious nor prying but innocent and utterly pure.

The seemingly wide-eyed sentiment here is but an entry point for Leopardi’s relentless examination of language, religion, culture, and politics, all written in secret in the family library and unknown until 1898. The rigorous discussion of these topics draws him to value above all valor, courage, virtue, vigor, pride, passion, simplicity, and particularity — traits we are likely to associate with Jackson and his followers, then and now. Of the urban elite, with its broad humanist declarations of rights, Leopardi is not so sanguine (one of the great ironies of the work is that it’s a deeply reasoned treatise against reason). The aim of the French revolution, for example, according to Leopardi, was to “create a perfectly rational and philosophical people,” a scheme that couldn’t work. “I pity them,” he went on, “not because of their chimerical belief that they could bring about a dream and a utopia but because they did not see that life and reason are incompatible, and instead assumed that a total, precise, and universal reliance on reason and philosophy should be the foundation and source of the life and strength and happiness of a people.”

Ultimately, Leopardi’s argument leads him to refuse the possibility of innate truth and absolutism. For Leopardi, “There is almost no other absolute truth, except that All is relative.” This conclusion of Leopardi places him, of course, in opposition to about every thinker of his time.

Biddle, at 20, traveled to Greece, in 1806, also wide-eyed and hopeful to banish the cynicism he had seen taking over American public discourse. There, “he survived the equal dangers of Greek plagues, rising from the swamps, and Greek bandits, descending from the mountains,” says Kennedy in his 1989 masterwork, Greek Revival America.

He looked like Byron, and though his writing was stately rather than poetic, a passion for Greece equal to Byron’s keeps breaking through. That passion sustained him amid flies and fools and petty larceny, as he searched for architectural symbols to proclaim his personal and political visions.

The experience tempered Biddle’s pure belief in the ancient world. “The present generation of men is more civilized, more moral, more enlightened, better than any of those whose exploits are transmitted by history,” he wrote in his diary while traveling.

But Biddle, says Kennedy, “saw ancient temples set against a romantic landscape and wrote of them as villas in the Pennsylvania woods.” He quickly began to advocate a Greek revival in architecture, a movement that took off in 1825, as the American economy exploded (thanks largely to Biddle’s careful management of the B.U.S.). It relieved American builders of having to rely on Renaissance tradition for architectural inspiration, and gave the new nation an original form that carried political symbolism and meaning. During the 1820s, he would see to it that each of the two dozen branches of the B.U.S. in cities across the nation, following the lead of the central branch on Chestnut Street in Philadelphia, be designed in the Greek Revival.

The very concept of a banking system would have been anathema to Leopardi, as it was apparently to Jackson, who deplored banks as corrupt and bankers like Biddle as monopolists. “He professed to be the deliverer of his people from the oppressions of the mammoth” B.U.S., writes economic historian Bray Hammond, and to prohibit paper money — currency or script — disassociated from its base in gold and silver.

Money is foremost abstraction — doubly so as paper or as credit — and so Leopardi wrote, in May, 1821, “today, instead of doing, we have to calculate; and where the ancients did things, the moderns count them, and what were once upon a time the results of actions are today the results of calculations.”

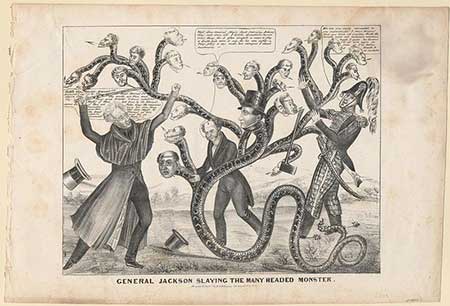

Biddle, to be sure, mastered the calculations until Jackson removed most of the public deposits from the B.U.S. during the Bank War and Biddle miscalculated by further restricting lending from the bank — austerity that led to a depression. As an 1836 cartoon showed, Jackson with his populist appeals to workers and farmers had tamed the “many headed [hydra]” of the Bank. (Though soon, Biddle would regain his power, triumph over Jacksonian monetary policy, and then ultimately lose everything, after being accused of fraud.)

Writing from his family estate in the village of Recanati, from which he had recently tried to escape, Leopardi goes on condemning the entire monetary system, such as it was, sounding as much like a Jackson partisan, as any “true Democrat” and suggesting, at least, that symbols of the classical Greek and Roman worlds in those old political cartoons might be reversed.

Observe then… the immense toils and miseries needed to procure money for society. Begin with the labor in the mines and the extraction of metals and go on to the last stage of the process, the minting of coins. Observe how many men are required to suffer constant and unrelenting unhappiness, disease, death, slavery (either unpaid and violent, or mercenary), calamity, pain, suffering, and travails of every kind, in order to procure for other men this instrument of civilization and supposed means of happiness. • 27 December 2013