No one on the globe is making comics like Yuichi Yokoyama. That seems like a foolish thing to say — after all, I haven’t tracked down every cartoonist on the planet to do a comprehensive compare/contrast analysis — but I feel like it’s a pretty safe bet nevertheless. Completely unconcerned with the conventional aspects of storytelling — most notably plot and character — Yokoyama has built a body of work that is utterly unique in its near-relentless exploration of motion, sound, and structure. His comics are enthralling and dynamic, but at the same time drained of emotion, as if an alien race was trying to mimic a typical comic but couldn’t quite get the hang of it.

Yokoyama began his career as a fine art painter but moved to creating manga out of a desire to “draw time” (he has pointedly noted in interviews that he is not familiar with most other forms of comics, manga or otherwise). His initial book, collected in English in 2007 by Picturebox, was titled New Engineering and featured battles in libraries and autonomous construction projects. Travel, about four men that go on a train trip, came to the US in 2008. Garden followed a group of people exploring a strange, expansive landscape. Color Engineering saw him experimenting with mixed media.

Most of these comics center around exploration and discovery, usually observed from a novel perspective. Travel, for example, is not about the destination but the minute details observed on the trip, like the way a ray of sunlight reflects off a passenger’s sunglasses or the pattern rain droplets make on a window. The garden in Garden contains little organic life but rather rivers made of rubber balls, rooms full of soap bubbles, and entire towns set on casters. Nothing is revealed about how these structures came to be or what purpose they serve. Simply observing their existence is enough.

While Yokoyama eschews traditional storytelling conventions, it would be inaccurate to say that nothing happens in his manga. Indeed, things are in constant motion in his world. Nothing ever stays still. Objects transform or unfold to reveal new uses. Machines carry things hither and yon. Artificial structures are erected lightning-quick. People are always hurriedly moving from one location to the next, often pointing out what they see along the way.

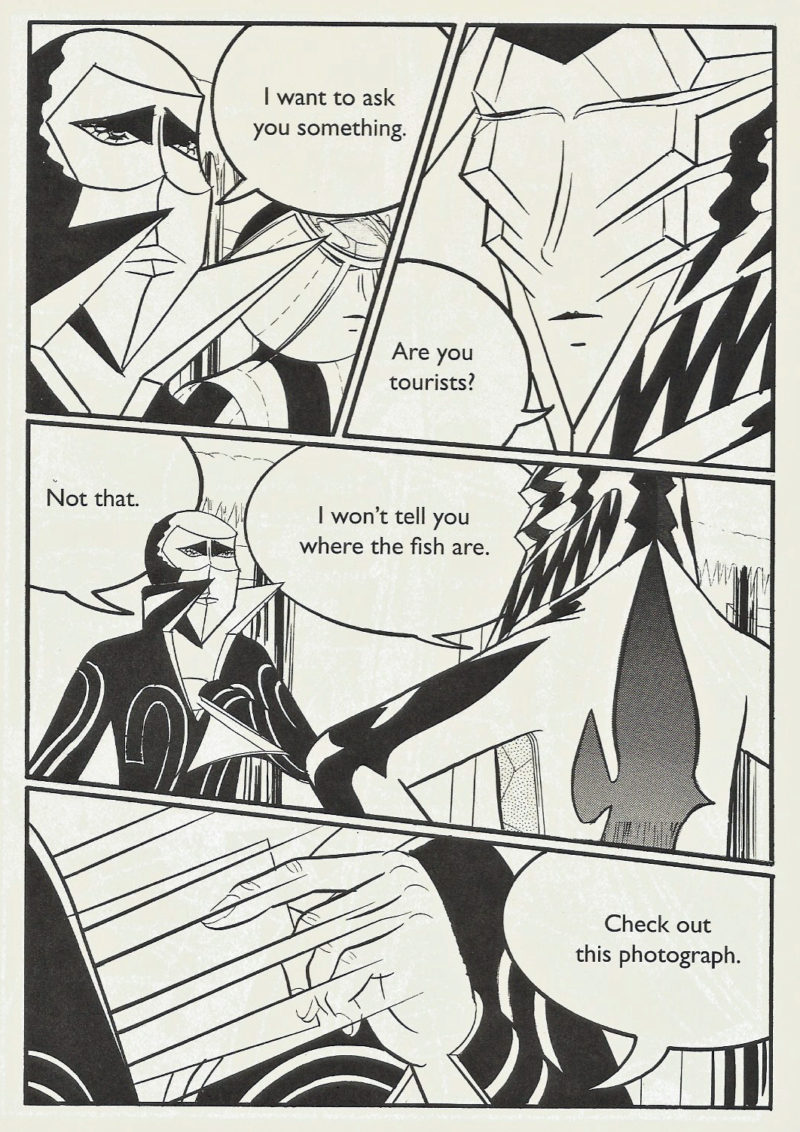

Indeed, whenever Yokoyama deigns to have his characters speak (many of his stories, including Travel, are wordless), their dialogue is always flat and dispassionate. There is no inner life to be revealed, no deep backstory to be ruminated upon. No one ever expresses anger, amusement, or sorrow. Or any emotion really. Instead, they merely offer a running commentary on what they’re witnessing. (Typical exchange: “The Water looks cold.” “The air is also cold.”)

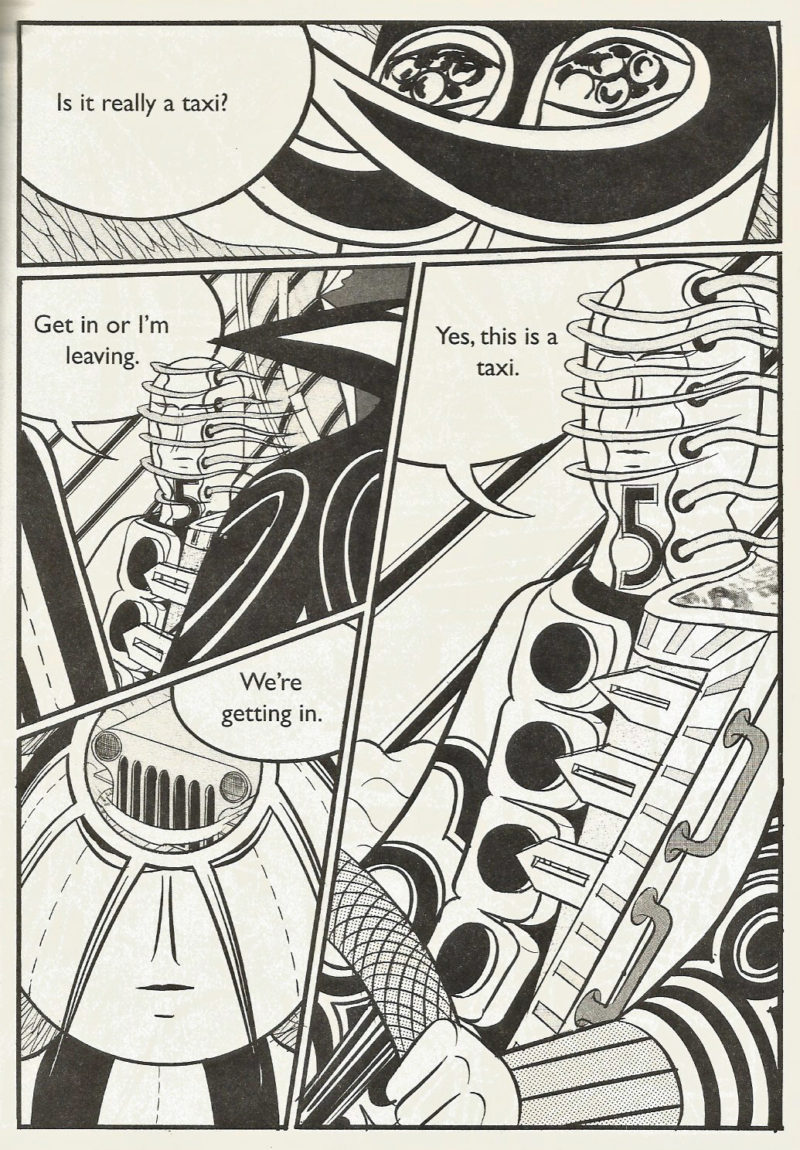

It’s in the characters’ visual design that Yokoyama’s imagination takes flight. While his figures seem to be composed of basic geometric shapes and move about in a determined but robotic fashion, they often wear elaborate, multi-patterned clothes that defy conventional fashion sense — one character’s shirt consists of the letters to his name moving across his torso like a electric billboard.

That flair for ornamentation extends to the heads of his figures as well. Not content to draw simple, recognizable facial features, Yokoyama’s universe is populated with folks that have all manner of strange noggins atop their shoulders, often verging on the surreal or abstract. A character might have a baseball for a head, for example, or an eyeball with spikes radiating outward in a sun-like pattern. Or a — well, it can be difficult to describe sometimes, really.

In 2013, Yokoyama began what he dubbed his “gekiga” trilogy, with World Map Room. Now, the sequel of sorts, Iceland, has arrived. (A previous volume, Outdoors, is expected to come out in English at the end of the year from Breakdown Press.)

“Gekiga,” a term coined by manga-ka Yoshihiro Tatsumi, loosely translates as “dramatic pictures.” Initially, it was a way for Tatsumi and other like-minded artists to differentiate the more serious comics they were making from the kid-friendly stuff that dominated the market in the late ’50s and 1960s. Sort of like how we Westerners tend to use the term “graphic novel” instead of “comic” to describe more than a funnybook with a spine.

Eventually, the phrase came to be associated with a genre of manga aimed at older (i.e. over 21) men — one that featured action, violence, and the occasional bit of female nudity. Perhaps the best example of this is the long-running series Golgo 13, about a seemingly unstoppable assassin.

At first glance, it can be hard to tell how World Map Room and Iceland fit within this notion of “gekiga.” Beyond the whole “no plot” thing, there’s little physical violence in Yokoyama’s comics, and his characters generally tend to be male — or at least they appear to be. Yet a closer read reveals Yokoyama taking some elements of hard-boiled noir to flavor his manga.

In both World Map Room and in Iceland, everyone seems hostile and suspicious. One man in Room, for example, complains of thieves breaking into his home, which is under constant surveillance. There’s a taut aura of menace in both books that never uncoils, mainly because we’re never privy to any of the characters’ motives or plans.

If you look at the plot of Iceland, you can see elements cribbed from your average detective novel or crime story. Three people, some of whom resemble characters from World Map Room but are not necessarily the same people, arrive at a cold seaport town. They enter a seedy bar where the TV is blaring and ask the customers if they’ve seen a fourth man, passing around a photograph. So far, so good. But then it turns out the man is out back, lying in the snow. Together, the four men get in a taxi and speed out of town. A patron at the bar, meanwhile, declares the group a bunch of “nobodies.” The end.

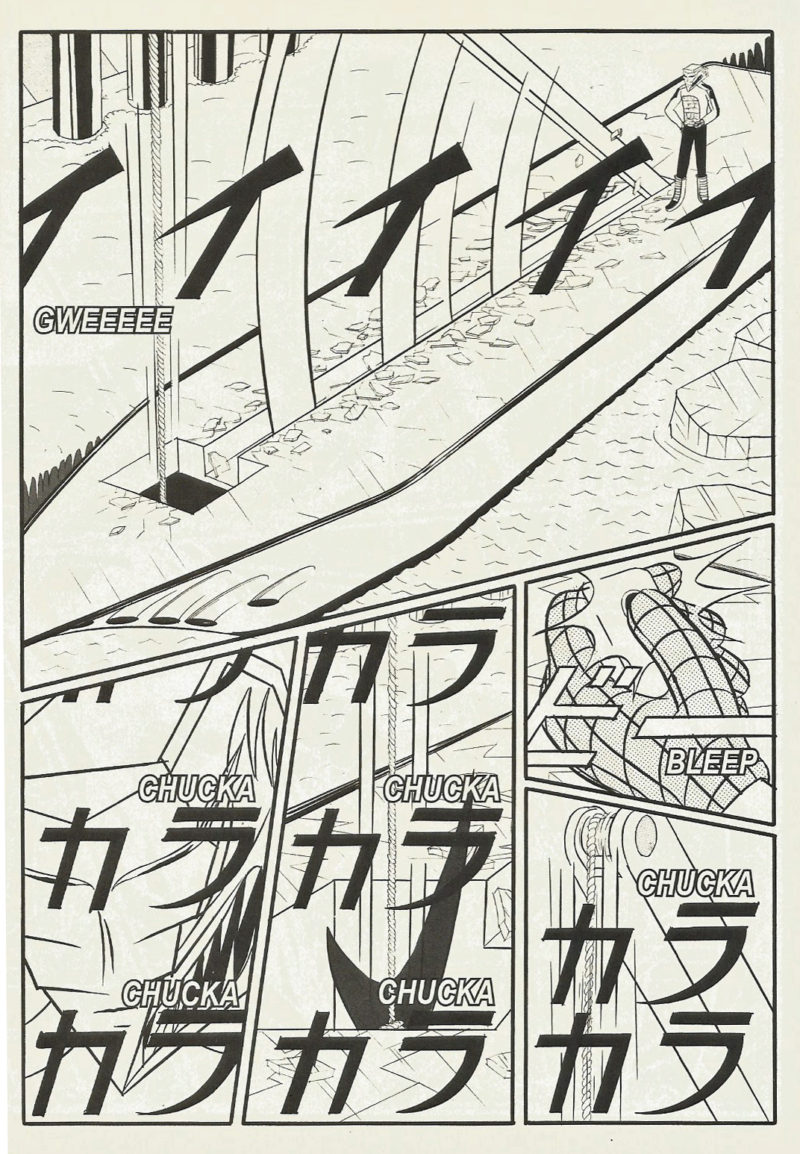

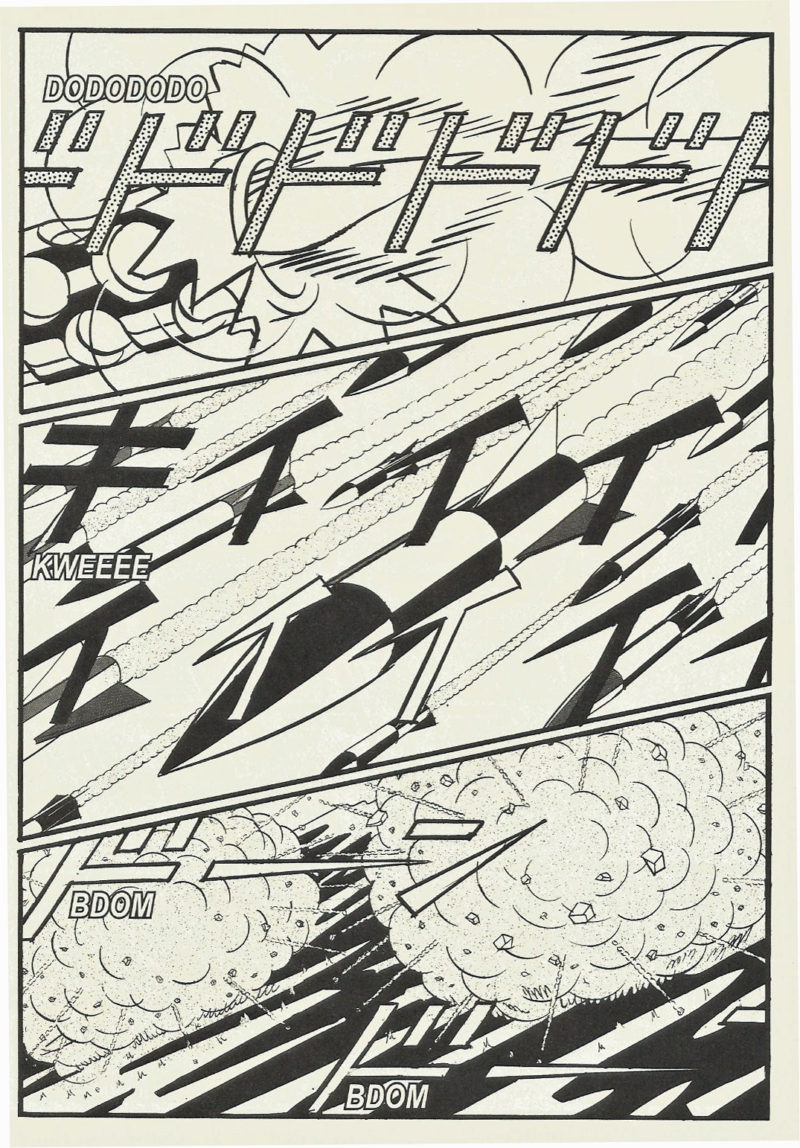

That blaring, big-screen TV is a crucial element of Iceland. As the trio attempt to interrogate the bar patrons, images of war and destruction — bombs flying, explosions, tanks, submarines, and for some reason a guy playing guitar — consume the background behind them, and for a page or two take up the comic entirely. As they try to speak, giant sound effects and onomatopoeia cover the characters (apparently the TV’s volume is broken) in big Japanese letters (Yokoyama’s lettering has always been a crucial element of his composition). This is a very loud comic.

So what’s going on here? Is Yokoyama attempting to comment on the saturation of violent images in our media and how it isolates us and makes us suspicious of each other? Is he slyly trying to interject a bit of action in a comic that stubbornly refuses to initiate any? Is he just playing with familiar genre tropes in his own idiosyncratic way? Or is it that he just really likes drawing explosions?

It could be all of these, it could be none of them. Yokoyama is an elusive figure who doesn’t reveal much in interviews so it’s unwise to ascribe too much in the way of themes or intent. Whatever the case, Iceland just further underscores the fact that Yokoyama remains one of the most intriguing and exciting artists making comics today. Far from being dry or lifeless, his comics pulse with a vibrancy and curiosity that make each new volume a treat. Iceland might be far-removed from what we generally consider to be your average comic book, but it’s far more fun than them. •

All images are copyright Yuichi Yokoyama.