The release of the first issue of DC’s Mister Miracle, a 12-issue limited series written by Tom King and illustrated by Mitch Gerads, was heralded with the sort of hosannas that are normally reserved for church. The A.V. Club called it “dazzling” and “emotionally wrenching.” Entertainment Weekly declared it “by far the best comic on stands right now.” io9 dubbed it “one of the best comics of the year” and, in another article, said there was “no better way to honor [Jack] Kirby’s contribution to the comics world.” And Comic Book Resources went as far to breathlessly declare that “King & Gerads Have Redefined Mister Miracle, and Possibly Comics.”

You see where I’m going with this, right? Mind you, Mister Miracle (now up to issue four as of this writing) is far from a bad comic — it’s frequently entertaining and engaging — but it simply cannot bear the weight of all this excessive adulation. More to the point, this sort of overpraise is to some degree symptomatic of the manner in which certain superhero fans will glorify anything that reeks of a certain amount of sophistication and flair. Especially if it adds dollops of realism and grit to that shiny, spandex surface.

Mister Miracle is the creation of Jack “King” Kirby, arguably one the most significant and influential American cartoonists of the 20th century. With Joe Simon he created Captain America and invented the romance comic genre. With Stan Lee in the 1960s he gave birth to The Fantastic Four, The Hulk, Thor, The X-Men, and almost every other noteworthy figure in the Marvel Comics universe.

In 1970, fed up and feeling (rightly) that he would never receive the royalties and credit due him, Kirby left Marvel and went to the only place he could go at the time: DC Comics, the competition.

There, Kirby created what became known as the “Fourth World” saga, an epic, overarching story told between four interlocking titles: Forever People, New Gods, Jimmy Olsen, and Mister Miracle. The mini-line was sadly cancelled before Kirby had a chance to bring it to a close, but DC has brought the characters, especially the malevolent tyrant Darkseid, back to the fold on numerous occasions.

Mister Miracle, a.k.a. Scott Free (Kirby was never one for subtlety), is the biological son of the benign, noble Highfather but raised on Darkseid’s ravaged and savage world of Apokolips. Fleeing Darkseid’s clutches as a young man, he becomes a professional escape artist and superhero who, thanks to his otherworldly technology, is able to escape even the most impossible traps.

Scott Free has traditionally been portrayed as a relatively sunny, positive character, putting his traumatic past behind him to build the relatively quiet life of a minor celebrity and occasional hero with his wife, fellow New God Big Barda. That’s eradicated in the very first few pages of King and Gerads’s series as Scott is shown on the bathroom floor of his home, having slit his wrists in an apparent suicide attempt.

From there, Scott seems to wander through his comic in a depressive daze, unsure of the reality that surrounds him or how to shake the clear unease and depression that plagues him. New Gods and old friends appear to talk to him, but are they really there or is he imagining things (Barda informs him that one visitor died of cancer months ago)? Highfather has apparently died at Darkseid’s hands, but is that what really happened? And all the while, a war seems to be raging between the forces of good, led by Orion, Scott’s belligerent adoptive brother, and Darkseid’s armies.

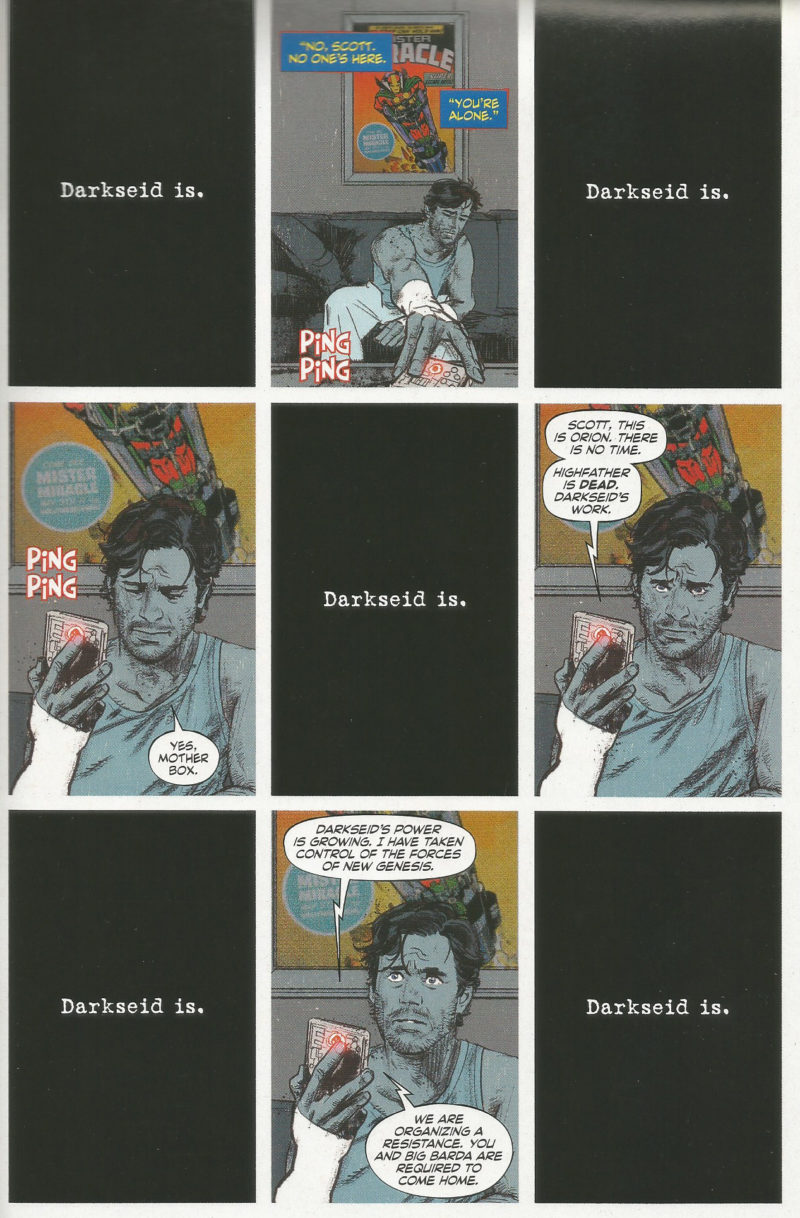

In the original Fourth World saga, Darkseid sought the “anti-life equation,” which Kirby portrayed as a metaphor for handing over your free will and individuality to a totalitarian, warlike system. In King and Gerads’s hands, however, it becomes an analogy for depression — Scott fears that the anti-life equation might somehow be “inside him” and this fear is underscored by black panels that frequently interrupt the story by declaring in white text that “Darkseid is.”

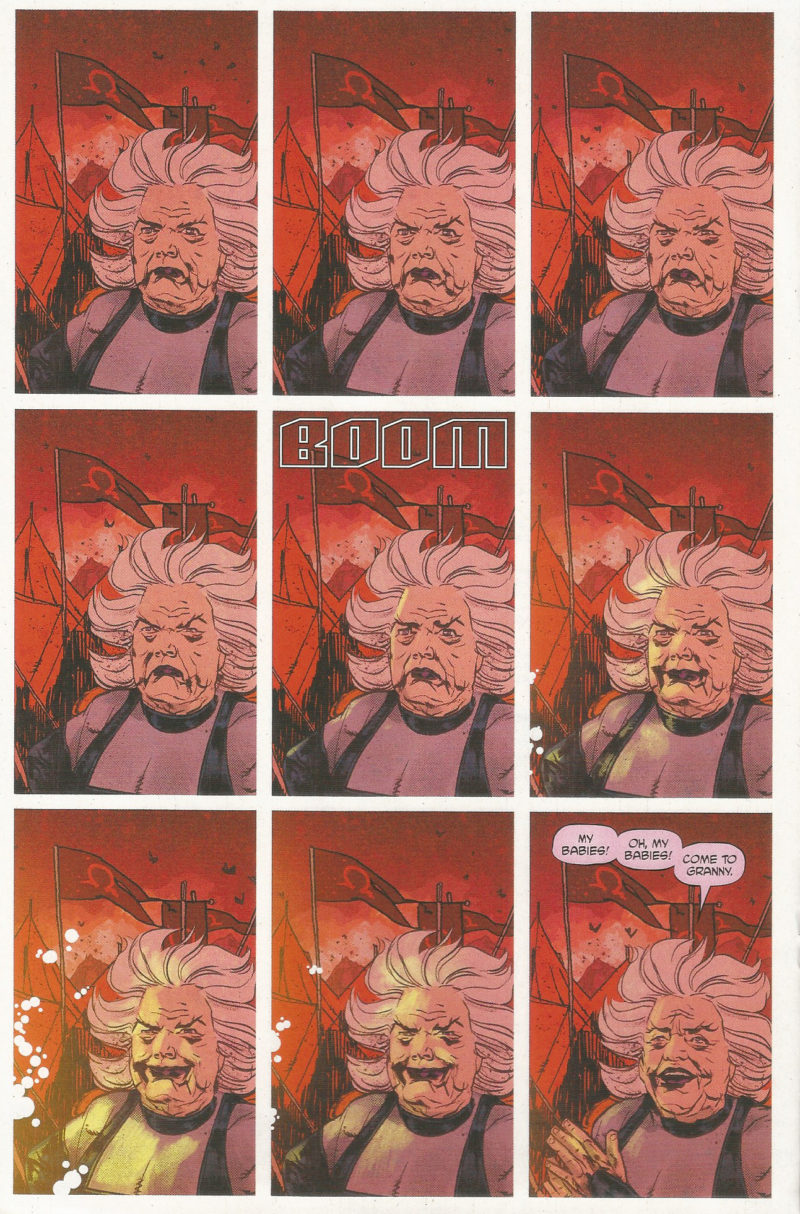

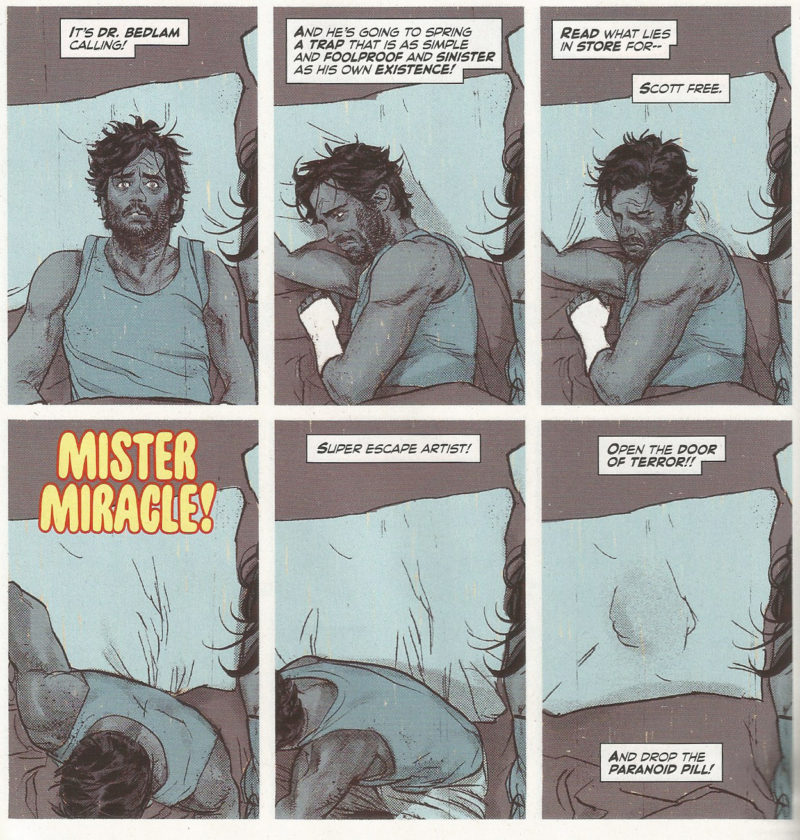

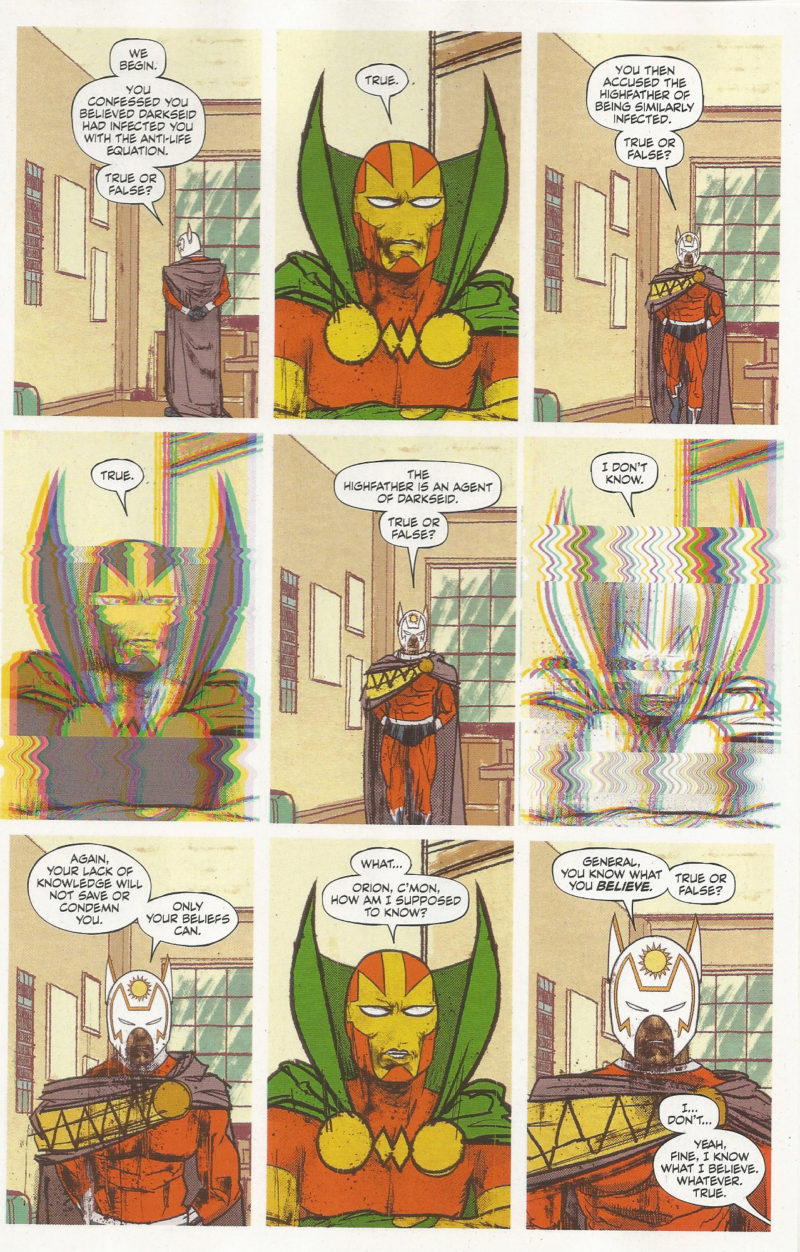

King and Gerads hammer home Scott’s despondency via a rigid nine-panel grid structure and use of repeated images that only differ slightly in subtle facial expressions and body movement, suggesting a certain monotony and claustrophobia to Scott’s routine, even when battling para-demons (King appears to be a big fan of this structure, as his previous comics like Omega Men and Sheriff of Babylon made frequent use of it as well). Occasionally, King will interject this with a passage of Kirby’s hyperbolic text taken from the issues of the original Mister Miracle series (“Hold it dear reader, we’re not done with you yet!”). At times, the panels also seem to break down and waver, as if we’re watching this comic on an old TV that was getting bad reception, another suggestion that what’s happening to Scott might be some sort of Jacob’s Ladder scenario.

Initially, these sequences come off as clever, or at least a refreshing variation on the over-the-top flashiness that superhero comics still seem to rely upon. But it doesn’t take long before all these tropes start to feel like schtick. You wonder when the comic is going to break out of (I dare not say “escape”) its overly mannered, narrow structure and do something else. There are also moments where the metaphors are so on-the-nose that they come off as too melodramatic or worse, corny.

It certainly doesn’t help that many of the rave reviews the comic has earned act as though all these motifs — the rigid grid, the depressive hero, the “is it real or a dream” — are somehow innovative to comics (spoiler alert: they aren’t).

The other thing is that the whole “Can Mister Miracle escape himself?” thing has been done before. Recently. Grant Morrison, Pasqual Ferry, and Freddie E. Williams II covered familiar ground in their own Mister Miracle series back in 2005-06 as part of Morrison’s Seven Soldiers metaseries event. And that only ran for four issues.

More to the point, what does Mister Miracle actually have to say about depression or mental illness? We’re four issues into the series thus far — about a third of the way through — and we have been treated to plenty of scenes of Scott Free moping about at home and on the battlefield, but it’s difficult to ascertain what the authors feel about his despondency other than it’s a bad thing. If Mister Miracle has any insights or wisdom about despondency, it has yet to share them with the reader. And if, as the comic seems to strongly suggest, Scott Free’s depression is not brought on by a chemical imbalance but by some sort of supernatural or sinister exterior force, doesn’t that cheapen the message? Is Scott’s depression just a ruse to get tell another overly simplistic story of good versus evil? This comic has style, to be sure, but is that all that it has?

Regardless, fans — at least those who write blog posts and go onto social media — can’t seem to get enough of this series. Every generation, it seems, wants its own Watchmen (another devotee of the nine-panel grid), an excuse to feel as though they are a cut above the usual fanboy because they appreciate a certain gravitas with their fisticuffs and derring-do.

I feel a little bad beating up on Mister Miracle in this fashion. It’s a perfectly fine comic, with some genuinely entertaining moments (the fourth issue has a running good gag involving a veggie tray). But best comic of the year? Better than Emil Ferris’ My Favorite Thing Is Monsters, more conceptually daring than the final issue of Kevin Huizenga’s Ganges? More harrowing in its portrayal of depression than Josh Cotter’s 2009 Driven By Lemons? No, no, and no. For all its willingness to play with the format, Mister Miracle remains an exceptionally safe comic — is there any doubt Scott Free will overcome his demons or that it will be revealed that some evil conspirator has been manipulating things behind the scenes?

It gets tiresome seeing readers and critics shell out the plaudits for work that can be described as good at best. To suggest that Mister Miracle is somehow the height of sophistication does a disservice to the comic, to its creators, and to the art form in general. •

All images provided by the author and DC Comics.