Explaining what motivates his work as an artist, Kader Attia speaks in his native French of réparation. He does not simply mean “fixing” as we might be tempted to translate into English. Instead, réparation can be thought of as transformation. You get a semblance of the original, but in the process of mending an object is always made new.

We do have a more precise translation in English, the less common “reparation,” literally mending as well as making amends for a wrong or injury. The images of needles and sutures and scars conjured by this definition move more closely to what Attia intends to signify.

In October 2016, after receiving the prestigious Prize Marcel Duchamp, Attia gave an interview with presenter Thomas Baumgartner for Radio Nova. Listening to Kader Attia’s mind at work reveals a constant weaving of different cultural influences and worldviews. He is preoccupied with reparation, less as a subject per se than as a symptom of much broader processes: cultural, political, and psychological. This subject of reparation, Attia insists, is “at the same time ethic and aesthetic, intellectual and emotional, poetic and politic.” Navigating speech with halting consideration, the artist clearly relishes the apparent contradictions. Despite his words’ care, enthusiasm for that which language cannot easily pin down comes through in his tenorous voice. The power of language shapes more than the nuanced meaning of words; as the artist is keenly aware, its influence subtly molds our entire worldview.

Yet, what ultimately makes the question of reparation so compelling is not its recalcitrance, but its urgency. In Europe, and France in particular, long-strained differences of culture are now bound up in a complex web of alarming social crises — systemic poverty, racism, extremism, and terrible violence — which offer no hope of simplistic conclusion.

Speaking of his native France (and of the Western world in general), Attia says we attempt “to erase a wound, as if to hide it’s ever having existed.” He contrasts that against a different attitude, one encountered in different cultural settings still outside the prevailing stream of Western thought — places in the Middle East and in Africa. In these non-Western contexts, Attia explains how injuries are instead allowed to take on an extremely expressive form. It can be taken for granted in such contexts that the act of reparation gives an object new life. Something broken never returns to the original form; always and irrevocably, it is changed.

Reparation, then, is a lens through which Attia might parse out otherwise untangle-able concerns — about individuals and society, about consciousness and culture — bound up in the knot of human experience. It’s a preoccupation that has led the artist, now in his early 40s, to the far reaches of the world. The result is a criticism of Western culture capable of making such diffuse issues as terrorism and smartphone obsession begin to cohere.

Grasping what Kader Attia’s perspective has to offer in such turbulent times first requires context. Namely, an appreciation of the fractured society he was born into and how it came to be that way.

Perhaps nowhere in France are the strains of societal change more acutely felt than in Kader Attia’s home city of Paris and its banlieues — a once-banal term for the variety of French suburbs which now applies pejoratively to ghettos inhabited predominantly by those of Arab and African descent.

Paris’ banlieues lie mostly beyond the Périphérique, a beltway forming a physical barrier between the City of Light and these concentrations of crime and unemployment. Writing in the New Yorker in 2015, George Packer described one archetypal Paris banlieue as “a disordered landscape of graffiti-covered walls, glass office buildings, soccer fields, trash fires, abandoned industrial lots, modest houses with red tile roofs, and clusters of 20-story monoliths — the cités,” housing projects erected in the Brutalist post-war architectural style, now in varied states of decay. These two Parises have for decades existed in parallel segregation. A sense of isolation has been left to fester among a younger generation whose identity has been shaped first and foremost by the banlieues.

Questions of integration and societal difference in France are inextricably tied to the country’s colonial history. Many of the first waves of African and Middle-Eastern immigrants came to France in the wake of colonial independence during the 1960s. Independence for France’s former colonies was not always achieved peacefully, and the Algerian War of Independence was the longest, bloodiest and most complicated of colonial conflicts. The experience of that war in Paris was further complicated by the presence of migrant families of Algerian descent who fervently protested the democratic government’s imperialistic war to subdue their home country.

“It’s hard to underestimate,” Packer wrote of the Algerian War of Independence in 2015, “how heavily this intimate, sad history has been repressed.” He recounts one of the more egregious events from the long history:

On October 17, 1961, during demonstrations by pro-independence Algerians in Paris and its suburbs, the French police killed some two hundred people, throwing many bodies off bridges into the Seine. It took 40 years for France to acknowledge that this massacre had occurred, and the incident remains barely mentioned in schools.

Such historical realities never fit comfortably within the predominant cultural narrative of France. That narrative, still potent in the present day, vaunts values like liberté and égalité to construct a national self-image as standard-bearer of enlightenment; redoubt of reason, tolerance, and free speech. But France too can be understood through contradictions.

Attia labels this societal reflex “colonial denial,” a knee-jerk in the face of glaring cognitive dissonance. He mentions “denie colonial” with a wry wit that undertones a depth of first-hand experience at laying bare this collective absurdity. He offers a counter-perspective on French history through which to understand current events.

In Attia’s account, the message received by successive waves of immigrants and refugees arriving from the former French colonies during the second half of the 20th century was simply: “integrate yourselves into this society.” Implied in this posture is a curt disregard for the countless identities, values, and lifeways of individuals. Rather than communities of established and arriving residents in France engaging in desperately needed cultural discourse, immigrants were simply expected to turn a new leaf.

This refusal to address the difficulties posed by modern cosmopolitan co-existence is, to Attia, the original sin of France’s post-colonial quagmire. Expecting others to act “contrary to their pre-existing selves,” as he puts it, breeds deep individual crises of humiliation. Unattended, such feelings can fester into neglect or even resentment. Instead of collective attempts at understanding and reconciliation, Paris got ghettoization and mutual stigmatization of each community as a respective “other.”

Whether stemming from fear or pride some blend of both, it is an attitude that remains at the heart of France’s failure to integrate generations of their own citizens of Arab and North-African descent. One need only recount the litany of now-infamous place names — Charlie, the Bataclan, the Promenade d’Anglaise — to call to mind that failure’s tragedy.

Now, facing what former President Francois Hollande declared France’s “new normal,” a deeply fractured France is in desperate need of reparation. Art, Attia insists, has unique license to approach this tabooed history and raise the uncomfortable questions that need to be raised.

“I found in art,” Attia says searchingly, “the possibility to pass on a message while at the same time connecting on these essential questions of living together.” As a sort of prism through which such a question is passed, Attia has found the power to touch people more profoundly than through politics.

Finding confidence in his words, the artist’s voice rises. “I believe art is sincere,” Attia resolves. “C’est ca, en fait! A filmmaker is sincere, a writer sincere, a musician sincere, all while holding certain beliefs. It’s a sincerity you simply don’t find in politics.”

Attia’s understanding of social reparation is a process akin to what Claude Levi-Strauss called “bricolage,” a group’s ability to forge novel solutions to social problems by drawing on the existing material within the collective consciousness.

To illustrate, Attia offers the mundane example of a leather jacket. From a Western view, a leather jacket carries a symbolic set of more-or-less agreed-upon social connotations. This given meaning is modified even further by such things as the jacket’s style or condition. A mind grown accustomed to these layers of meaning is unlikely to bother separating the implied symbolic meaning from what is fundamentally no different from the most primitive animal skin. Constantly stitching together the same rudimentary elements, society is continuously engaged in a process of reparation. All too often, we simply fail to recognize it, so convinced of our coded differences rather than our more fundamental similarities.

Attia runs swiftly through this explanation as though it were well-practiced. The question of reparation, he has long since discovered, possesses many layers. Social reparation, he says, is “rudimentary,” alluding instead to something “much more complex, metaphysical even, beyond our typical understanding.” The more he interrogates the received worldview from which he began, the more layers are revealed.

For a moment, Attia casts hesitantly for abstract language to convey the deeper layer apparently at the heart of his convictions. Then his voice steadies. He returns to cross-cultural reportage, speaking decisively once more from his own personal experience.

It was deep in the Congo where Attia says he first discovered “un certain puissance,” a power “prior-to inconceivable to my eyes.” Early in his adulthood, under the auspices of a civil service project, Attia spent time among the Aka people, commonly called pygmies. Here, in an early encounter with radically different lifeways, Attia observed “a reflection of the sacred, something retained that shines through the mélange of cosmologies superimposed upon a society which was by turns Islamized and Christianized.” He speaks of a connection retained among the Aka to ancestors and to the supernatural: a knowledge now unknown to the West.

Attia assigns to the Aka tribespeople “a keen sensitivity,” which for the first time brought him into contact with “a fascinating and receptive mystery.” He attributes to this sensitivity also “a certain plasticity of spirit” through which “things comprehended without having been learned directly or informed through reason” are more readily understood and acknowledged. This spirit of perceptivity and spontaneity are for Attia embodied in the Aka tradition of polyphonic chant. The beauty of the music lies in its confluence of individual voices, each contributing to the progression of the whole without being subsumed in it (a sample can be heard at the 44:15 mark of the interview recording).

What seems then to be a type of intuition, or something akin to our modern understanding of it, is for Attia a capacity inherent in humanity. Though this type of understanding might resonate in the West, it seems obscure only because it fails attempts to be pinned down rationally, to pass through our litmus test of cause and effect.

These responses are telling of the Western spirit, so contradictory to all Attia describes. Modern Western societies, he says, still pride themselves as products of that triumph of reason called the Enlightenment. Contrasting the two modes, he says, yields “a certain passivity” reflected by the Western view, “a separation from the power and intelligence of this world we fail to find a means of controlling.”

“What I learned in Central Africa,” Attia concludes, “is that rational and irrational power are equivalent, and perhaps interchangeable.” Beyond the purely rational order of the typical five senses, Attia attests to a subtler susceptibility to vibrations “at the same time emotional and rational.”

It was a powerful self-discovery which Attia says nurtured him in this formative stage, revealing the potential for new modes of understanding. The comparative lens is essential to Attia’s critique of Western culture, and it’s no coincidence he has drawn his most compelling insights from non-Western contexts, places historically on the receiving end of the legacy of European colonialism. This insight likewise awoke the artist to a different type of colonization — the tyranny and limitations of his own inherited worldview. This colonization of thought, unavoidable for anyone brought up in Western or any other culture, presents for each an error in need of repair.

Understood as symptoms of the colonization of Western thought, such errors manifest in a certain passivity which quickly compounds. The unwillingness to face the difficult problems of coexistence lies at the root of disastrous social fissures. Equally pernicious to Attia is a “neo-liberal” paradigm which reduces each individual to a consumer in pursuit of a uniform idea of happiness. Even with the ubiquity of communications technology like smartphones, Attia is skeptical of such devices’ ergonomic focus on ease and seamlessness, seeing a potential blunting effect on the very faculties of intense critical thinking required to comprehend how such devices work and how their complex systems are governed.

It’s as though all these symptoms conspire in the Western mind to add up to a ruthless calculus. Our appetite for instant gratification and immediate advantage denies to others — even, quixotically, to ourselves — an inherent worth. Attia calls these corrosive errors the “oxymorons of reason.”

In response, Kader Attia advocates a radical embrace of the opposite. To overcome the “hive-mind,” the uniqueness and variety of every individual should be celebrated. Only by acknowledging in an individual or group the fundamental grandeur of others, he insists, can we begin to repair our errors. As with the polyphonic chants of the Aka, many voices come together, but no voice is subsumed. Above all, it will require an insistent conscientiousness. Awareness of this Western passivity calls for an intentional willingness to pose difficult questions to the social group. For France, that means “continuing a conversation that was halted — or which never began,” he says, to acknowledge a legacy of colonization and failed assimilation.

In this work of cultural reparation, Attia insists music and art have as much a role as debate and dialogue. Confronting the unfamiliar through vibration and resonance, as Attia learned himself in Central Africa, can create a “dizzying whirlwind” in which “you are removed from the typical order of things.” In this way, art has a vital ability to “force us over our hang-ups” and get outside singular ways of thought. The rational and emotional are equivalent and interchangeable.

Paris today, Attia laments, has lost some of its spirit of free discourse, long bound-up in the French national image in which Paris is the penultimate cultural capitol.

“In Beirut and in Dakar, I found an even greater liberty of speech than in France . . . a manner of relishing debate, even the disagreements.” Noting cities that boast ancient histories of ethnic or religious coexistence, Attia observes an ability to grapple with difficult subject matter vital to communal life.

It was in this spirit that in 2016 Attia unveiled his latest project: perhaps not quite a work of art but the latest chapter in his continual exploration, it is a multipurpose arts venue and communal space called La Colonie. Even the name itself is an invitation to that dialogue.

Attia describes La Colonie as an “open space” in northern Paris. Designed in homage to the multi-tier bal musettes of the 1920s and ’30s, La Colonie offers the possibility for multiple activities to be going on at any given time. In Attia’s own words, it’s a place to “come, have a drink or a coffee, alone or in a group, but always with the chance of a conversation or debate — be it intellectual, political, or artistic.”

Mixing symposia and academic discussion in the same space as art, dance, and general socializing, Attia hopes to ignite in Paris a new spark of shared understanding. Describing the diversity of Parisians dancing and reveling at his new venue’s opening night festivities, Attia articulates an atmosphere of “togetherness in difference.” It’s a vision of the world he undoubtedly hopes to see reverberate far beyond La Colonie, the ever-searching artist’s latest approach to reparation in a country longing for harmony. •

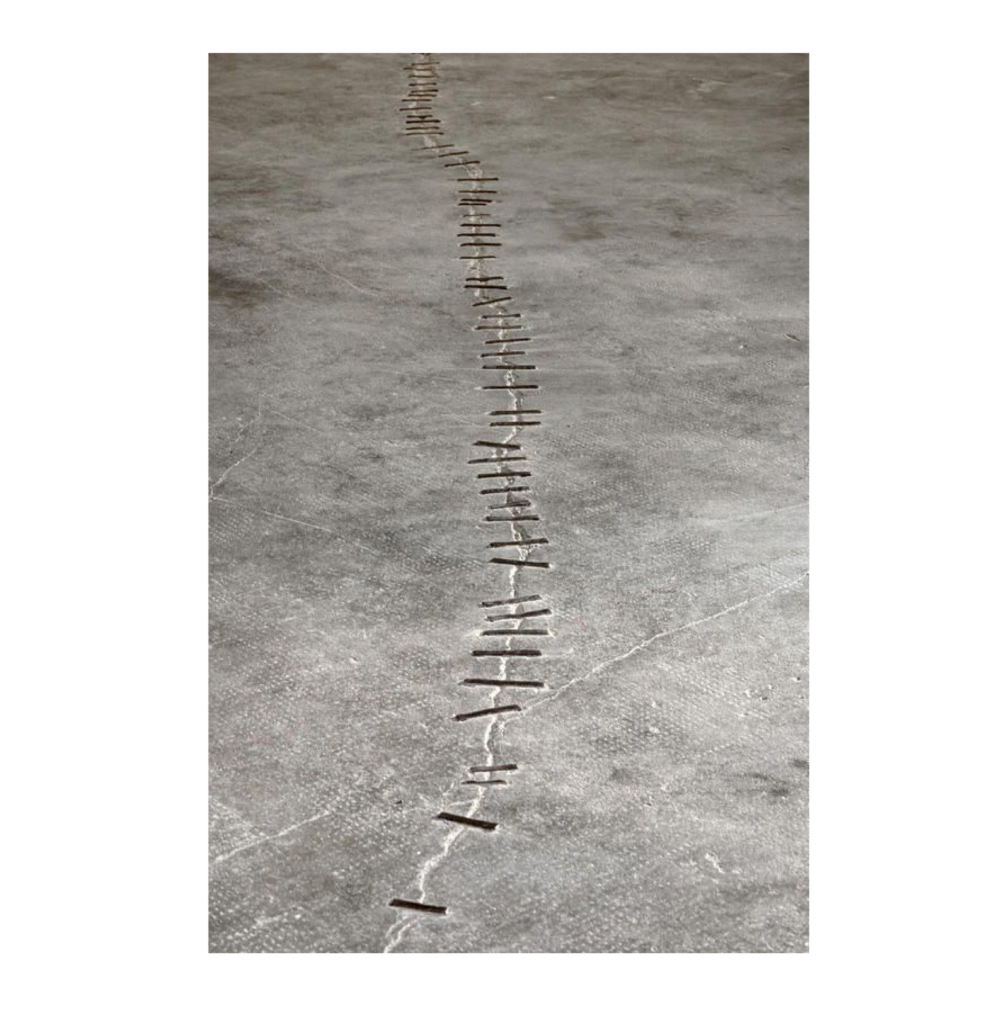

Feature Image created by Emily Anderson. Photos of Attia installations courtesy of Blaise Adilon, Alexandre Dulaunoy, and Katja Nevalainen.