In the fall 2017 season, the National Gallery in London mounted a show entitled “Leonardo, Michelangelo, Raphael around 1500.” Here were three of the greatest artists of any period, with several masterpieces on display, and each work breathtaking and all tied nimbly together. The point was to illustrate a moderate argument — namely that Michelangelo learned from Leonardo about capturing the expressive relation between the Madonna and the Infant — but more importantly, the show made clear what genius and skill can achieve.

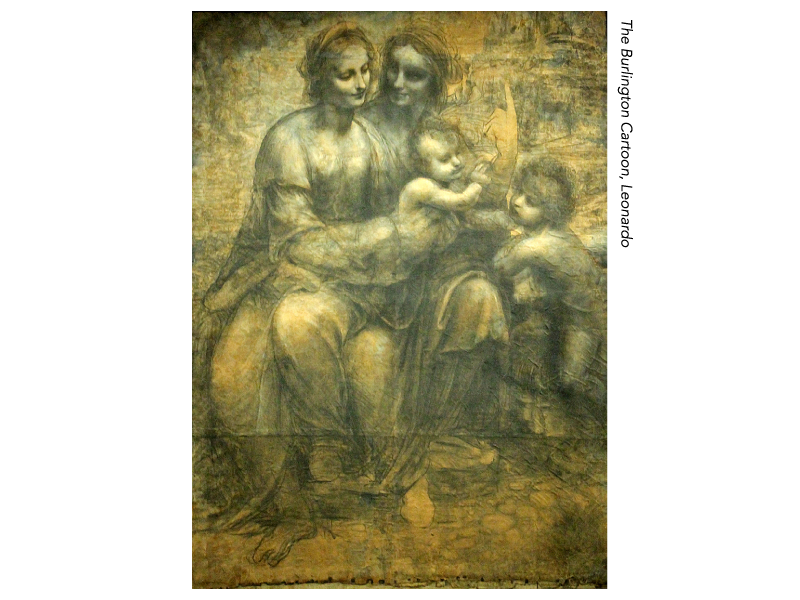

The seven works included one marble sculpture by Michelangelo, the “Taddei Tondo” (ca. 1504-1505); one drawing by Leonardo, the “Burlington House Cartoon” (ca. 1499-1500); and five paintings in oil or tempera. These latter were depictions of the Madonna and Child, four of which included John the Baptist, and one exception, Raphael’s “Saint Catherine of Alexandria” (ca. 1507). Chief among the Madonnas were the drawing, Leonardo’s “Virgin of the Rocks” (ca. 1491-1499 and 1506-1508), and Michelangelo’s unfinished “Manchester Madonna” (ca. 1497). The three Raphaels included his “Ansidei Madonna” (1505), the “Madonna of the Pinks” (1507), and “Saint Catherine of Alexandria,” the only one without the Madonna. The spirit of the exhibit was captured by the contrast between the three great names and the almost off-handed reference to “around 1500.” This conveys the notion that the works of monumental genius are ratified, as it were, by an approximate point of time. All artists, perhaps the greatest ones most of all, work and exist in time even as they shape and suffer that perfidious and relentless medium. Art history casts the net that helps — or nearly so — bring the issues into a knowable frame.

This exhibit features the Michelangelo “Taddei Tondo,” left unfinished but complete enough to form a key part of the argument. (It was graciously lent for the occasion by its owners, the Royal Academy.) The curators maintain that Michelangelo saw Leonardo’s “Virgin of the Rocks” and was struck by the classical look of repose on the angel and the two infants, the Christ child and the Baptist. The sculptor’s response was to make his infant Christ express a look of troubled withdrawal, setting it as an argument against, or even a refutation of, Leonardo’s calm, an emotion dictated by his adherence to classical aesthetics. Pushing the claims, the curators add that these two poles of artistic intent were in part formed by a “deep animosity” between the two artists as they vied for commissions from the Pope and others. The look on the Infant’s face in the tondo is indisputably not calm. One could go further and say the look registers the child’s foresight into his passion and crucifixion. One could shift the ground of argument and say what really matters is the expressiveness that Michelangelo has wrested from the marble, which virtually pulses with life, just as the Madonna’s turban and blouse are alive with the feeling of a softly woven textile. Whatever Michelangelo took away from his viewing of Leonardo he used it to perfection in combination with his own aesthetic. Classical calm was not a part of it.

However convincing or not the curator is in bringing Leonardo and Michelangelo face-to-face and pointing to a contrast in temperament and vision, other points are noticed and serve to instruct. What both artists mastered around this time — and passed on to subsequent artists — is skill at grouping and posing the figures (especially the Madonna and her child) in such a way that religious piety and humane feeling intertwine. However, because of the nature of the contention and the choice of focus, Michelangelo for the moment appears the greater artist. But this leaves us to deal with Leonardo and an almost mystical reputation.

Much more has been written about Leonardo than almost any other Renaissance painter. One highly impressive example is that of T. J. Clark, whose essay on the “Madonna of the Rocks” appeared in 2012 in the London Review of Books. There, Clark took account of a different National Gallery exhibition, a bringing together of the two versions of this magnificent work, the one housed at the Louvre and the other at London’s National Gallery. After 500 years, the two pictures were brought face-to-face in one room. Most experts generally agree that the London version was painted several years after that of the Louvre, though in the past there was some doubt cast on the London version’s authenticity. A veritable feast for art historical scholarship and speculation is set out due to the complicated history of this work and Leonardo’s difficulties with it, and Clark was equal to the task. His argument dazzles and convinces, though some might find it too subjective in its charged descriptions and quick surmises. Too long and detailed for summary, the essay traces the history of the two versions and ends by preferring, more or less, the one in the Louvre. He argues in comprehensive detail for the London version’s weaknesses and the Louvre’s version’s greatness. Exploring “the painting’s overall crystalline abstraction — its nearness without tangibility,” he nominates the Louvre version as the final masterpiece of the Quattrocento. Then he rounds onto the National Gallery version. Having dealt with any doubts about its authenticity, he shows just how remarkable it is. At one point, he has a brisk summary of the painting and its reception: “The London panel is a formidable object, brilliant, ice-cold, entirely conscious of its power; and connoisseurs, almost as much as the general public, have always found it hard to like.” This appears to anticipate the disposition of the National Gallery curators. At times Clark involves us in Leonardo’s technique, at others his sense of life in space and flesh. The Infant has changed in texture, placement, and form between the first Louvre version and the second National Gallery one; “he has become a miniaturised Michelangelesque athlete.” This brings us back to the questions of influence and affinity.

The Burlington Cartoon used to be set off by itself in a half-enclosed space of its own to minimize its exposure to light. Here it was liberated to join its fellow masterpieces. I first saw it, without any prior knowledge, 40 years ago when I first visited London. Alone in the room with this drawing I felt for the moment as if I were its patron. As our only full-scale drawing by Leonardo its rare mysterious appeal results from the almost casual attitudes of the Madonna and St. Anne and the liveliness of the two infants. No classical calm enters the esthetic here. Instead a relaxed liveliness emits an ethereal quality that results from the charcoal medium with its white chalk highlights, and the possible use of a light wash. Another version, now lost, was exhibited publicly in Florence and did much to increase Leonardo’s reputation. For years the drawing has been one of the Gallery’s most prized works. Having the cartoon and the tondo just feet apart, we can see how the two “non-painted” objects invoke the vastness of the Gallery’s spaces. This leaves room for others besides Leonardo and Michelangelo.

•

Raphael’s entry into the group of Madonnas and Infant may at first appear as a way of exhibiting a third great artist. Keep in mind that of the seven items in the exhibit, six are in the National Gallery’s collection, the only exception being the tondo belonging to the Royal Academy. Selection is at the crux of the curatorial effort, but rather than isolate works or overwhelm us with more instances, the works form a unity of thought, a way of rethinking relationships, echoes, and lines of affinity. Raphael has two Madonnas with Infant, the well-known “Madonna of the Pinks” and the “Ansidei Madonna.” These are but two of the 33 Raphael Madonnas listed by Wikipedia, and they constitute a range of effects and emotional atmospheres seldom if ever equaled by any other artist.

The “Madonna of the Pinks” has the tenderness and naturalism of expression that somehow manages to avoid the sentimentality that is the bane of other artists whose countless Madonnas follow. The infant reaches for the small flower even as the Madonna holds another behind the infant’s back. There appears no intent in this withholding but it creates a sense of emotional space, symbolizing the mother’s putative control and the child’s dependency on maternal care. This humanizing conveys fragility. The wall text, for its part, calls the viewers’ attention to the subtle shading of the Madonna’s garments, and this surely adds to the total effect. But more is at stake. For those viewers who are religious believers there remains the doctrinal point that here the infant is already much greater in terms of spiritual power, but at the same time growing towards divine strength and knowledge. For non-believers such as myself it may be difficult to calibrate the exact theological fine points. Some have suggested that the particulars of the affectionate tie between the two subjects in the painting anticipates the Immaculate Conception. But it is the moment of the offering by the mother and the equally gentle reaching by the infant which gives Raphael his true subject, the gift that is both object and moment.

Raphael shines in all three of his canvases. One of the more striking effects of his Saint Catherine is the way it stands as a prototype of devotional portraits of blessed women (and less often blessed men). Of course Raphael did not set out to paint a prototype. A prototype in paintings results from an achieved excellence — in design or form or symbolic meaning, among other effects. Raphael’s Catherine solidifies the type of purity-in-sainthood. She is shown standing full-length, her head turned slightly to her right and her eyes looking heavenward. This painting is an outlier among the group at the exhibition, since it doesn’t include the Infant. The success of the pose and the facial expression will be repeated thousands of time but few will have the evident skill and affect of Raphael’s painting. The cumulative effect of his skills creates an overall luminous result that sets him apart from the classical calm of Leonardo and the intense terribilita of Michelangelo. Decades ago I was taught that Raphael was truly great, but he fell short of the stature of Leonardo and Michelangelo. This was said in spite of the overpowering reputation he earned among his contemporaries and for two or three subsequent centuries. But through the occasion of this exhibit we can say what should more than satisfy: he is a master of the High Renaissance equal to, but different from, the others. The exhibit allows us to adjust our measurement of Raphael by showing us what he took from both of the other masters and his skill in absorbing and adapting the most important aspects of a great painting.

The other two paintings that fill out the offering for the exhibit are Raphael’s “Ansidei Madonna” from 1505 and Michelangelo’s “Manchester Madonna” from 1497.

The Raphael was painted for a patron, probably Nicholas of Bari, a bishop, who also appears in the painting along with the Infant and St. John the Baptist. Raphael uses the balanced symbolism of office as he depicts the bishop with his crozier while John holds the crucifix on the other side of the Madonna. Though studied in its poses, the painting notably contrasts the stiffness of Nicholas with the almost brooding stance and face of the Baptist, as if anticipating by several centuries the distinction between church and crown or sainthood and power. Placing the additional figures in the space of the painting — especially using an adult version of the Baptist — generates a more complex array of expressions, though it could be said that this detracts from the intimacy between Madonna and child that was brought to such a high point by Michelangelo and Leonardo. Showing the Bishop reading from a book (apparently the Bible) and the Madonna seated on a wooden throne contributes to the formal, studied tones, perhaps reflecting the patron’s desire or character. It demonstrates a visual grammar that would become increasingly typical in later centuries.

The unfinished “Manchester Madonna” by Michelangelo serves as the source of insights about how painting was done “around 1500.” Only in his early years at the time he painted this, the unpainted section of the picture shows a clear underdrawing and there are indications that the picture would have been completed in stages, two technical procedures practiced by this point in the Renaissance. The group of figures is assembled with four angels attending the Madonna and child, two angels on each side. The left-hand pair of angels is present only by the underdrawing, and much of the left side is unpainted. On the right side the two angels read from a scroll, often taken to refer to the prophecy of Christ’s future suffering, by 1599 a staple of iconography. The Infant, seated on his mother’s lap, reaches for a text being held by one of the missing angels. The two forms of reading material, so to speak, may suggest the interplay of doctrinal order and sacred prophecy. Like Raphael’s addition of his patron to a painting devoted to the Madonna, here the additional figures open up the range of symbolism that religious art uses to delight and instruct. We read the icons in a context different from the one that brought them forth, but with such satisfying visual pleasures at stake, the context can be thickened and opened up at the same time.

This highly rewarding show can be prized for the way it makes art history and aesthetic genius not only approachable but worth contemplating. Big issues and telling details, of course, are always support for a valuable experience. Placing masterpieces before us so we can appreciate both their moment and their historical reach allows the High Renaissance to be properly valued. Thus the superior art exhibit becomes one of our most richly satisfying events.

This exhibit runs until 28 January 2018. •

Feature image by Emily Anderson.

Leonardo da Vinci’s Virgin of the Rocks courtesy of ItalianRenaissance.org

The Birmingham Cartoon courtesy of Frans Vandewalle on Flickr.

Madonna of the Pinks courtesy of dvdbramhall on Flickr.

Unfinished Manchester Madonna courtesy of Jean Louis Mazieres on Flickr.