My father does not have an illustrious history with cooking. You wouldn’t know that looking at him in the kitchen now — when my grandmother’s health was failing, he studied with her so that he could make her classic desserts, like fluffy cream cake, spiraling jelly rolls, and not-too-sweet apple pies. But before that, I knew my father to have exactly one dish — Welsh rarebit.

In his own words, “It wasn’t much.” He melted Velveeta with a large can of tomatoes, and maybe an egg (Dad: “I don’t remember”). What he does remember is making the dish for his roommate and a friend when they were living in Pittsburgh, and right as they were about to pour the rarebit over crackers, realizing that everything — the table, the plates, and the crackers — was covered with tiny ants.

If it’s not already obvious, I’ll note that this dish was made in the days before my dad met my mom.

Although I find my father’s version of Welsh rarebit unappetizing (I’m not a Velveeta gal, and the ants don’t help), his rendition really is very similar to the classic Welsh rarebit — at its core, the dish is simply cheese on toast. One of the earliest published versions, in Hannah Glasse’s 1774 cookbook The Art of Cookery, Made Plain and Easy, provides these instructions for a Welsh rabbit (more on that name in a moment):

Toast the bread on both fides, then toaft the cheefe on one fide lay it on the toaft, and with a hot iron brown the other fide. You may rub it over with mustard.

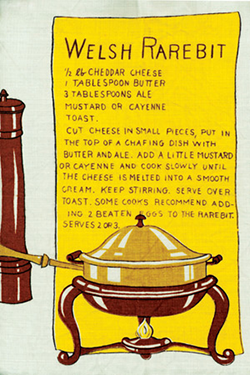

This is actually one of the few Welsh rarebit recipes that simply calls for melting the cheese on toast; most versions are actually a cheese sauce, where the cheese has been melted with butter; ale, milk, or cream; and paprika or mustard. Some versions call for eggs; some don’t. Same thing with tomatoes. But all feature that delicious, fatty, and warm cheese served over toasted bread.

While everyone agrees that cheese and toast are at the heart of a good rarebit, one thing that people can’t agree on is the origin of the name. In The Oxford Companion to Food, Alan Davidson points out that in print, “Welsh rabbit” — the version in Glasse’s book — predates “Welsh rarebit” by 60 years. (Although a dictionary from 1836 claimed that the word rabbit “is sometimes a corruption of Rare-bit.”) As for the Welsh part, one theory is that the “Welsh” name is simply derogatory — implying that Welshmen are either too poor to afford rabbit or too stupid to understand that this cheese sauce has no rabbit in it. This explanation would seem to be bolstered by the existence of a similar dish, Scotch woodcock, which contains no actual woodcock, but eggs and anchovies on toast. (A side note — instead of whole anchovies, some Scotch woodcock recipes call for a strong British anchovy paste known as “Gentleman’s Relish,” which has to be the best name for a condiment ever.) Davidson does point out, however, that “One thing which is not in doubt is Welsh fondness for cheese,” and that the name Welsh rarebit could simply be recognition of that fondness.

You know who else loves cheese? Bachelors. (Just look at all the blue-box mac-and-cheese in their cupboards). In fact, my father was only one in a long line of bachelors who prepared Welsh rarebit. The dish might actually be one of the first bachelor foods, thanks to the late-1800’s bachelor’s favorite proto-microwave cooking tool, the chafing dish.

You know, the chafing dish — those metal trays-within-trays, heated underneath by a small flame. When I first read that they were the bachelor’s food-prep tool of choice, I was surprised. I had always assumed that chafing dishes were historically the domain of the very wealthy. Granted, this came from very anecdotal evidence: one, that the Granthams’ breakfast is served out of chafing dishes on Downton Abbey, and two, that chafing dishes are used at hotels and business buffet events. (Yes, I know that tonging-out bacon from the Marriott’s silvery warming tray isn’t the highest-class thing, but it did convey a certain sense of wealth to me as a child that remains to this day — I certainly can’t afford to keep an entire tray of bacon warming in my dining area.)

But while we primarily know chafing dishes as glorified food warmers, they were actually used for cooking, not just for serving. It makes sense; at a time when a single person wouldn’t necessarily have an oven in his apartment, the simple, tabletop chafing dish, heated from underneath by an alcohol burner, provided a way for nearly anyone to cook. Indeed, there’s even a men’s cookbook from 1895 that features my new favorite title ever, The Bachelor and the Chafing Dish: With a Dissertation on Chums. The author cites the chafing dish’s “very general use by both men and women, its convenience for a quick supper or for a dainty luncheon, and its success as an economical provider where it is necessary — all this is putting the chafing-dish on a queenly dais.”

And if the chafing dish is the lady, Welsh rarebit is its lord. The Bachelor and the Chafing Dish actually says exactly that, describing, “toasted or cooked cheese” — the base of rarebits — as “the king of the chafing-dish.” 1900′s The Bachelor Book, meanwhile, notes that Welsh rarebit is an excellent after-theater food, and says this about serving the rarebit in perfect bachelor style:

If there is one bachelor there should be one pretty girl, two bachelors, two pretty girls, ad infinitum, to say nothing about the chaperone, who may be pretty or ugly so long as she is shortsighted and harmonizes with your decorations.

But having an excuse to hang out with pretty ladies (“Hey baby, wanna come back to mine for some hot cheese sauce?”) isn’t the only reason why Welsh rarebit was eaten as an evening food. See, Welsh rarebit was traditionally served as what Taco Bell has tried to tactfully call FourthMeal — late-night drunk food. It has all the hallmarks of today’s post-bender eats — cheesy, fatty, with plenty of bread to soak up the booze. (OK, I don’t think that actually works, but it’s what I’ve tried to convince myself was happening every time I’ve had a misguided late-night burger.) What’s interesting about Welsh rarebit’s typical late-evening consumption, though, is that the dish is also supposed to induce absolutely batpoop-crazy dreams.

You might’ve heard the rumor before that eating cheese before bed can cause nightmares. It’s a claim that has never been proven, although a 2005 study from The British Cheese Board stated that different types of cheese tended to give different kinds of dreams — Stilton for bizarre ones, cheddar for dreams about celebrities. Anyway, it’d seem to make sense that if cheese cause bad dreams, and Welsh rarebit is made of cheese, that’s what’s at play.

But the post-rarebit nightmares are a thing of their own. In fact, they were so ubiquitous around the turn of the century that they inspired multiple works of art. One book from the time, Welsh Rarebit Tales — a “gastro-literary experiment” — collected short stories based on dreams from several friends who all ate Welsh rarebit (along with broiled lobster, mince pie, and cucumber salad), immediately before bed. Filmmaker Edwin S Porter made an early short, “Dreams of a Rarebit Fiend,” that features a man serving himself rarebit from a chafing dish (while also imbibing several drinks, which might get a bit closer to the real source of rarebit nightmares…) and then flying on his bed over the city. This film was actually inspired by perhaps the most well-known Welsh rarebit art, a series of cartoons from the Windsor McCay, who is best known for Little Nemo. Also called Dreams of the Rarebit Fiend, the strips each feature a protagonist going through a crazy experience, only to wake up and curse the rarebit he or she ate. In the book collecting the comic, the first page features a man trying to cross a busy street only to have his limbs chopped off one-by-one by passing carriages. Finally, the woman dreaming the dream wakes up — it was about her husband, who’s thankfully safe at home in bed — and she says, “I’ll eat no more rabbits, no.”

(Also, while I have no scientific information as to whether or not rarebit actually causes abnormal dreams, I can tell you that the evening after serving a rarebit recipe to a friend, he spoke in his sleep — something that he claims he doesn’t normally do.)

But while Welsh rarebit is known as late-night bachelor nightmare food (a description that I can say, completely unsarcastically, makes me super-excited to eat it), there are also many rarebit variations that (thankfully?) don’t seem to have the same nightmare-inducing qualities and are mighty delicious. Unsurprisingly, many of these first appeared around the time of the chafing dish gaining popularity in the late 1800s. There’s tomato rarebit and chicken rarebit. There are rarebits that call for cream cheese instead of the typical cheddar or American (most recipes agree that the cheese should be “mild,” but I made a batch of brilliant rarebit with sharp cheddar). There are the rarebits with things on top of them — golden buck is a rarebit with egg on top; add bacon to that, and you have Yorkshire rarebit (one of my personal favorites). There’s baked bean rarebit, in which you mixed leftover, mashed-up baked beans into the rarebit (a delicious concoction that my friend aptly called “burrito sauce”). And, while cheese and seafood doesn’t sound appetizing to many, there are a whole host of ocean- and river-dweller rarebits — such as sardine rarebit, halibut rarebit, and even oyster rarebit (around this time, oysters were so plentiful in America that being drunk and eating them cooked on toast wouldn’t make people think twice, whereas today you’d have to practically have the wealth and fame of a Kanye West for that dietary choice to seem sensible).

Over the next century, however, these rarebit recipes fell out of favor. Electricity in buildings became widespread, and chafing dishes disappeared from apartments. Eventually, Welsh rarebit became reduced to the processed-cheese sauce my father would stir up for his roommate.

And that’s a shame. I mean, you (hopefully) don’t need me to tell you that a cheese-and-beer sauce (or cheese-and-cream sauce) served over bread is delicious. But even I was surprised by how much I enjoyed some of these recipes — the salty, pungent sardines under the velvety warm cheese; the better-than-mac-and-cheese comfort of the baked bean rarebit; the why-is-this-not-on-every-brunch-menu decadence of the Yorkshire version. (Seriously. Restaurants, I had one bite of Yorkshire rarebit with its crispy bacon and runny-yolk egg, and I was ready to run into your kitchens and tell you how you’re doing everything wrong with your breakfast sandwiches.)

Moreover, it’s a shame these recipes fell out of favor because sometimes, we all need a little bit of a fast, comforting bachelor food, whether we’re bachelors or not. And even if your rarebit gives you crazy dreams, it’ll also give you a seriously delicious meal. • 3 June 2013

| Welsh Rarebit, |

Most Welsh rarebit recipes don’t stipulate what kind of cheese to use; in my experience, a mild-to-sharp cheddar is best, depending on your preference. Although the recipe was written to be made in a chafing dish, it can just as easily be made in a pot on the stovetop. Most Welsh rarebit recipes don’t stipulate what kind of cheese to use; in my experience, a mild-to-sharp cheddar is best, depending on your preference. Although the recipe was written to be made in a chafing dish, it can just as easily be made in a pot on the stovetop.

From Chafing Dish Possibilities by Fannie Farmer, 1898.

|

| English Rarebit, |

This variation calls for soaking the bread entirely in red wine. In testing, I found this to be both too soggy and boozy. I recommend following the instructions as below, but only putting 1-2 teaspoons of wine on each slice of bread, for flavor.

From The Art of Cookery, Made Plain and Easy by Hannah Glasse, 1774

|

| Baked Bean Rarebit, |

The zephyrettes mentioned at the end of this recipe have been lost to time; Nabisco can confirm that “1898 through 1914 Zephyrettes appears in National Biscuit Company price lists,” but they have no information on ingredients or style. One source I found said that zephyrettes could be substituted with saltines, but it did not mention how similar the crackers are. The zephyrettes mentioned at the end of this recipe have been lost to time; Nabisco can confirm that “1898 through 1914 Zephyrettes appears in National Biscuit Company price lists,” but they have no information on ingredients or style. One source I found said that zephyrettes could be substituted with saltines, but it did not mention how similar the crackers are.

Also, if your baked beans are salty, consider reducing the salt in this recipe or omitting it entirely.

From Chafing Dish Possibilities by Fannie Farmer, 1898

|

| Sardine Rarebit, |

I loved this, but I also love sardines. If you’re brave enough to step up to the sardine-and-cheese plate, you’re in for a treat.

From Salads, Sandwiches, and Chafing-Dish Dainties by Janet McKenzie Hill, 1918 |

| Golden Buck and Yorkshire Rarebit |

For these, I used the same rarebit recipe from the sardine rarebit above. Everywhere she says “chafing-dish,” just imagine “sauce pot.” For these, I used the same rarebit recipe from the sardine rarebit above. Everywhere she says “chafing-dish,” just imagine “sauce pot.”

From Salads, Sandwiches, and Chafing-Dish Dainties by Janet McKenzie Hill, 1918.

|