Heavyweight champion Lennox Lewis had just beaten a suddenly old Mike Tyson that evening at The Pyramid, and now Dad and I were back in the courtyard of our hotel in suburban Memphis, far from the crowds that spilled from the arena and choked the highways leading from downtown. I remember thinking as we sat there how the years had accumulated on him, how he had been unable to walk even short distances in the clammy haze that June week without breathing hard; I had to drop him off at the door wherever we went. But even so it had been a busy trip, full of big meals and good cigars and long conversations punctuated with laughter. He had never been in better spirits than when he had work to do, nor happier than when he had some jingle in his kick.

He’d come to Memphis to begin a book on Tyson, whom he had profiled for Esquire and later interviewed for Playboy. I had picked him up at the airport that Monday, and we spent the week on the go, slipping out of crowded press conferences and going off in search of local color. We stopped by Graceland, the National Civil Rights Museum and the crossroads in Mississippi where the bluesman Robert Johnson supposedly sold his soul to the devil — only to end up dead by the hand of a jealous husband who poisoned him. I had come along because I always did in these later years, if only to drive the car and serve as a sounding board for his ideas, plans, and assorted gripes. We were close that way. Given that we both also wrote under the same byline — I am not technically a junior — I sometimes wondered where he left off and I began. So I was not surprised when there was only one credential waiting for us at the press center, where the bewildered young man behind the counter looked at us and said: “So there are two of you.” Stuff like that was always happening.

With age 70 bearing down hard upon him as we convened in Memphis in 2002, Dad had by then written for better than 40 years, during which he had become celebrated, later disgraced, and I would like to think ultimately redeemed. While some of his contemporaries were better known, few surpassed his virtuosity with the language. For 13 years during the golden era of Sports Illustrated in the 1960s and 1970s, he followed Muhammad Ali and others on the boxing beat across the world, a journey highlighted by his classic coverage of “The Thrilla in Manila” between Ali and Joe Frazier in 1975. That story has been widely anthologized — including in The Best American Sports Writing of the Century — and is looked upon by the keepers of the canon as one of the finest pieces of sports reportage ever. A friend told me that, even today, a famous comedian he knows is able to extemporaneously recite the lyrical opening passage: “It was only a moment, sliding past the eyes like the sudden shifting of light and shadow, but long years from now it will remain a pure and moving glimpse of hard reality, and if Muhammad Ali could have turned his eyes upon himself, what first and final truth would he have seen?”

Good as some of his old stories are, it always seemed to me that his own was better than any of them; I only wish he had written it himself. Growing up in a working class section of East Baltimore, where his father had punched a clock for 40 years at Chevrolet, he played some baseball, discovered books, and hustled a newspaper job that led him to Sports Illustrated in 1964. I would like to be able to say that the work he did was the sum of his experience there, but the truth is more complicated than that, and perhaps ultimately irretrievable. I can only piece it together so far. But I do know that by the spring day in 1977 when he was called in and fired, he had wandered far from who he had been to a place walled in by shadows. He overcame some very long rounds to piece together a comeback with Esquire and fashion a lively finish in 2001 with his contrarian take on the Ali-Frazier trilogy, Ghosts of Manila. By then, he had turned an unforgiving eye upon himself.

“Novels, short stories, plays – I had those things in me, but I just never got down to work, did I?” he asked as we sat at the hotel. “Creatively, I just never grew the way I should have.”

I just looked at him, uncertain exactly what to say. Then: “You still have plenty of time.”

Carefully, he held a lighter to the bowl of his pipe. “Well,” he said, letting the word hang there. “What it comes down to is discipline. I just never had it. You have far more than I ever did.”

I changed the subject. “So, what did you think of Graceland? Elvis had some place. You should have gone onto his jet with me. You could have used it in the book.”

Clouds of smoke curled in the air as he said, “If there is a book.”

•

Given where he’d started, you’d have to admit he’d come far. Without any experience, he strolled into The Baltimore Sun in 1959 at age 26 and asked to see the sports editor, Bob Maisel, who just happened to have a job opening that summer day. Newspapers were like that then, especially sports departments; you could walk in off the street and see someone without an appointment. Dad handed Maisel a crumpled piece of typescript as a sample of his writing and told him, yeah, he had attended the University of Georgia. Fine, Maisel supposedly replied: The job is yours if you can prove it. Dad walked out of the building, went to Western Union and wired himself a telegram that read, in part: THIS IS TO INFORM YOU THAT MR. KRAM HAS SUCCESSFULLY COMPLETED THREE YEARS OF UNDERGRADUATE STUDY. Signed: Dean of Men, University of Georgia. Dad doctored it up some and took it back to Maisel, who glanced at it casually and gave him the job. “Could have happened that way,” says Maisel. “Probably did, ’cause I know I would have asked if he had any college.”

Baltimore became the subject of a cranky yet affectionate piece by Dad seven years later, on the eve of the 1966 World Series between the Orioles and Dodgers. The story was called, “A Wink at a Homely Girl,” the title drawn from the epitaph of fellow Baltimorean H.L. Mencken, the cigar-chewing, self-proclaimed agnostic who had waxed with loveliness: “If, after I depart this vale, you ever remember me and have thought to please my ghost, forgive some sinner and wink your eye at some homely girl.” “Wink” told of a Baltimore that has long vanished, the insular world Dad knew as a boy in the Canton section of East Baltimore, where men sat in the shadows of corner saloons reading the racing page and women wiled the summer evenings away on the stoop exchanging gossip. With a hard edge that assailed his old hometown as a “tunnel between Washington and Philadelphia,” the Baltimore piece ended with a special poignancy if you knew the circumstances from which he sprang. “Sonny, change will come here, too,” said Uncle one day by a pier, while the nephew stared vacantly at a freighter crawling through the water, and wondered where it came from, where it was going and if he would ever go.”

I think back on that old row house on Hudson Street in East Baltimore as a place of reassuring rhythms, of large beds and candy bowls and the cheerful presence of my uncles: Gordon, who sold chewing gum for a living; and Gerard, who still cuts hair at his barbershop in Canton. But the house I remember is far from how Dad experienced it in the 1930s and 1940s, when the two-story, three-bedroom affair was occupied by 13 warring members of the Kram-Arthur clan. Funerals were always gala events for the women of the family, who commented cheerfully on the expert preparation of the deceased, usually over a piece of crumb cake in the dining room. Beer and hard liquor flowed under clouds of cigar and cigarette smoke in the adjoining parlor, consumed with ascending glee by men with sagging bellies. Dad still went by his birth name back then, “George,” though he was better known as “Sonny” or “Otts” and — curiously — “Randy,” which he later picked up as a baseball player because, as his former army buddy Vince Stankewitz told me: “It made him sound like he could run faster.”

For an athletic young man who graduated high school 134th in a class of 144, the only escape from Hudson Street was playing ball. A three-sport star at all-boys Calvert Hall High School, Dad won second All-City honors in baseball his senior year, during which he played against Southern High School sophomore Al Kaline, later a Hall of Fame player for the Tigers. He did attend Georgia, but only for part of one semester, when he dropped out and was promptly drafted into the army. But instead of being shipped off to Korea, he slipped into a special services unit and played baseball at Fort Benning. There, he once slammed two home runs in a game off of Cardinals pitcher Vinegar Bend Mizell, who later became a Republican Congressman from North Carolina. Ex-big leaguer Tito Francona played with Dad there. “Good second baseman,” says Francona, whose son Terry manages the Red Sox. “George could have batted leadoff in the big leagues if he had caught a break. Did he ever sign?”

For an athletic young man who graduated high school 134th in a class of 144, the only escape from Hudson Street was playing ball. A three-sport star at all-boys Calvert Hall High School, Dad won second All-City honors in baseball his senior year, during which he played against Southern High School sophomore Al Kaline, later a Hall of Fame player for the Tigers. He did attend Georgia, but only for part of one semester, when he dropped out and was promptly drafted into the army. But instead of being shipped off to Korea, he slipped into a special services unit and played baseball at Fort Benning. There, he once slammed two home runs in a game off of Cardinals pitcher Vinegar Bend Mizell, who later became a Republican Congressman from North Carolina. Ex-big leaguer Tito Francona played with Dad there. “Good second baseman,” says Francona, whose son Terry manages the Red Sox. “George could have batted leadoff in the big leagues if he had caught a break. Did he ever sign?”

I have an old contract in a box somewhere that he signed with the Pittsburgh organization upon his discharge from the army in February, 1955. But it remains unclear what happened that year, just as it remains unclear how his career ended a year later with the Queen City Packers in the Man-Dak League in North Dakota.

He always said he had been beaned.

But I wonder.

“Otts showed up at a party that spring with Mercurochrome on his temple, and I said to him, ‘What happened to you?’” says old friend Charlie Hartman, who grew up not far from Hudson Street. “He told me he had gotten beaned. But there was no swelling underneath, so I said, ‘Otts, I think you just got cut out there, and you had to come up with a story.’ Oh boy, did he get angry! He said, ‘You SOB, we’ll settle this tomorrow in the ring. Meet me at the Y at noon.’ So for three rounds we pounded away at each other, then he threw his gloves down and said he was never talking to me again. But he got over it.”

Whatever happened out in North Dakota, it had to have been a letdown for him to come back to Baltimore in the spring of 1956. Married the previous December to my mother, Joan, he settled in with her in a small room above a fish store her grandparents owned in South Baltimore – and that July 1 was born. He once told me he stopped by the Lord Baltimore Hotel to see Francona, then a rising player with the Orioles. “I took a bus downtown and we had lunch,” said Dad, then employed at Maryland Dry Dock. “I asked him, ‘What happened, Tito? Why you and not me?’ Then he took a cab to Memorial Stadium and I took a bus back down to the fish house.” But it was during this period that he began reading for hours on end, given books early on by his old high school friend John “Jack” Sherwood, later a fine writer for The Washington Star. “Reading a book is not something Otts would have done back in school,” says Sherwood, who also cultivated in Dad the notion of writing for a newspaper. “They were pals,” says my mother. “So when Jack got a job on a newspaper, your father figured he would give it try.” Sherwood even helped Dad “fix” the telegram he gave to Maisel, saying now: “He showed it to me and I said, ‘Otts, no one is going to believe that.’”

Whatever happened out in North Dakota, it had to have been a letdown for him to come back to Baltimore in the spring of 1956. Married the previous December to my mother, Joan, he settled in with her in a small room above a fish store her grandparents owned in South Baltimore – and that July 1 was born. He once told me he stopped by the Lord Baltimore Hotel to see Francona, then a rising player with the Orioles. “I took a bus downtown and we had lunch,” said Dad, then employed at Maryland Dry Dock. “I asked him, ‘What happened, Tito? Why you and not me?’ Then he took a cab to Memorial Stadium and I took a bus back down to the fish house.” But it was during this period that he began reading for hours on end, given books early on by his old high school friend John “Jack” Sherwood, later a fine writer for The Washington Star. “Reading a book is not something Otts would have done back in school,” says Sherwood, who also cultivated in Dad the notion of writing for a newspaper. “They were pals,” says my mother. “So when Jack got a job on a newspaper, your father figured he would give it try.” Sherwood even helped Dad “fix” the telegram he gave to Maisel, saying now: “He showed it to me and I said, ‘Otts, no one is going to believe that.’”

It was not until then that Dad shed “George,” “Sonny,” “Otts,” and “Randy” and adopted the name he and my mother had given me three years before: Mark. By virtue of the fact that he had become a palindrome — his name spelled the same backward as forward — he immediately became somewhat of an oddity at The Sun, where the newsroom was still the way you’ve seen them in old B-movies: noisy typewriters, gin bottles in the bottom drawer, and card games between editions. For $65 a week he worked the copy desk and covered high school games. Within a year he was doing features and later a twice-a-week column, “Another Day,” gorgeously impressionistic pieces such as one on the perils of boxing called “All Gone and Quite Forgotten,” the beginning of which read: “For the faceless and the nameless, for those who know the smell of squalor and poverty, the fight game can be an exit…a light in a moonless world…a ride on a golden elephant.” A Sun copy editor forwarded his clips to a former colleague at Sports Illustrated, and in January, 1964, the young man who just a few years before had been scented vaguely of smoked eels suddenly found himself there in a stable of emerging stars.

One of them was fellow Baltimorean Frank Deford, who had been a copyboy at The Evening Sun before Dad worked there. “I remember thinking: “Where in the hell did this guy come from?” says Deford. “From the day he arrived at Sports Illustrated, he was looked upon as sort of a mad genius.” Early on they became close friends, even taking a stab at a screenplay together. Inevitably, they would talk about their old hometown, the characters there, the burlesque houses on The Block and so on. And yet as Deford observes pointedly: “We never talked about his Baltimore.” But I think I can understand why. That Baltimore stood in his psyche as if it were a downed airplane entombed in some uncharted jungle. Strip away the vines clinging to the wreckage and it is there you would find his Baltimore, a place where one day as a small boy he tiptoed down the narrow stairs of that Canton row house and came upon the cold body of his deceased grandfather, arranged in a wooden coffin and bathed in an amber light. For years, Dad held that memory close, only telling me when I had grown and he began letting go some of his secrets.

•

What I remember now is his back, the way it dampened with an enlarging oval of perspiration as he sat with his big shoulders crouched over the typewriter. Steeped in piles of newspapers and assorted coffee cups corroded with tobacco ash, he labored amid a drifting cloud of pipe smoke in Room 2072 wrapping up a piece on the National Marbles Tournament, which would later be included in The Norton Reader. I remember him chasing away a young woman that day who’d come early for his copy. Even at 17 I had to laugh, because he used every second allotted to him by a deadline, be it an hour or weeks. He’d get up, jam his pipe into his pocket, and pace, up this corridor, down the other, light his pipe and end up back at his office, where his typewriter remained with the same piece of paper in it on which 12 words had been written. His editor Pat Ryan refers to this as “stall walking” — what jittery thoroughbreds do to calm down – but eventually that sweat and tobacco paid off in prose that was like slipping into a velvet boxing robe.

Managing editor Andre Laguerre unlatched whatever raw abilities Dad possessed. The legendary Frenchman did not care if he had been to Georgia for three years or even three hours; in fact, a “Letter from the Publisher” in March, 1968 played up the phony telegram he concocted at The Sun as the act of a resourceful imagination. Laguerre divined in him a deep reservoir of moody sensitivities that could swell into uncommonly seductive prose. That became abundantly clear as his work developed in the ensuing years in an array of sharply observed pieces, none better than his 1973 profile of the forgotten Negro League star Cool Papa Bell called “No Place in the Shade.” That story begins: “In the language of jazz, the word gig is an evening of work: sometimes sweet, sometimes sour, take the gig as it comes, for who knows when the next will be. It means bread and butter first, but a whole lot of things have always seemed to ride with the word: drifting blue light, the bouquet of leftover drinks, spells of odd dialogue and most of all a sense of pain and limbo. For more than anything the word means black, down-and-out-black, leavin’-home black, gonna-find-me-a-place-in-the-shade black.” Dad would come to think of that piece as his finest effort at SI.

But it would be his work on the boxing beat that would bring him acclaim. Down through the years, few in that Ruyonesque galaxy of unrepentant rogues were spared the sharp point of his critical lance, including Ali, his entourage, the new Madison Square Garden, and rival promoters Bob Arum and Don King. “Boxing is a world of freebooters,” says Mort Sharnik, who covered boxing with Dad at SI. “And in that realm Mark was looked upon with much apprehension.” And yet as cynical as Dad could be, I think Sharnik is on to something when he says that he was oddly naïve. “Whenever you told him something, he would draw on his pipe and cock his eye in this skeptical way,” says Sharnik. “But a true cynic would not have allowed himself to be drawn in by some of the questionable characters Mark did. In that way there was always some rube in him.”

From the old Madison Square Garden to Mexico to Europe, Dad found his voice in the bold personalities that populated boxing back in the 1960s. But it was his coverage of a young Muhammad Ali that captured the eye of the public, which occasionally flogged him with letters accompanied by small boxes packed with animal excrement. Such were the passions that followed Ali into his government-imposed exile from the ring in 1967 for his position on the Vietnam War. By the end of it three-and-a-half years later, the unjustness of that ordeal and the emergence of Joe Frazier set the stage at the new Madison Square Garden for “The Fight of the Century” in March, 1971. With the jammed streets surrounding the Garden buzzing over the upset by Frazier, Dad hopped a subway back to the Time-Life Building, where the issue was being held open for his story at a considerable sum per minute. But in the one hour he had been allotted, he composed a story brimming with lyrical imagery that observed of Ali: “He has always wanted the world as his audience, wanted the kind of attention that few men in history ever receive. So on Monday night it was his, all of it, the intense hate and love of his own nation, the singular concentration and concern of multitudes in every corner of the earth, all of it suddenly blowing across a squared patch of light like a relentless wind.” Dad used to say those one hour jobs were “ball breakers”: “Editors pacing outside your door; you could feel their blood pressure go up whenever you stopped typing.” He did it again three years later for Ali-Frazier II.

From the old Madison Square Garden to Mexico to Europe, Dad found his voice in the bold personalities that populated boxing back in the 1960s. But it was his coverage of a young Muhammad Ali that captured the eye of the public, which occasionally flogged him with letters accompanied by small boxes packed with animal excrement. Such were the passions that followed Ali into his government-imposed exile from the ring in 1967 for his position on the Vietnam War. By the end of it three-and-a-half years later, the unjustness of that ordeal and the emergence of Joe Frazier set the stage at the new Madison Square Garden for “The Fight of the Century” in March, 1971. With the jammed streets surrounding the Garden buzzing over the upset by Frazier, Dad hopped a subway back to the Time-Life Building, where the issue was being held open for his story at a considerable sum per minute. But in the one hour he had been allotted, he composed a story brimming with lyrical imagery that observed of Ali: “He has always wanted the world as his audience, wanted the kind of attention that few men in history ever receive. So on Monday night it was his, all of it, the intense hate and love of his own nation, the singular concentration and concern of multitudes in every corner of the earth, all of it suddenly blowing across a squared patch of light like a relentless wind.” Dad used to say those one hour jobs were “ball breakers”: “Editors pacing outside your door; you could feel their blood pressure go up whenever you stopped typing.” He did it again three years later for Ali-Frazier II.

I have a photograph of him from the old days. In it he is standing on a train platform at Penn Station in New York with his bag by his side and leather coat folded over his hands. Sharply dressed in blazer and turtleneck, sideburns descending in the fashion of the day, he appears as Sharnik remembers him: “Like an escapee from a Dutch fishing fleet.” Dad had become an ambassador of rail travel in 1969, when engine trouble forced a jet he was on to return to Heathrow Airport, where the passengers were evacuated through a chute onto a foam-covered runway. He later told me, “I went to the bar and said: ‘Give me a triple, and work your way down. And then work your way back up again.’” Overseas journeys were then effected by passage on the QE2, during which he’d indulge in cold vodka and caviar and delve into Schopenhauer, who’d become an object of envy ever since he learned that the 19th-century German philosopher had withdrawn from society into a cork-lined room. Once, upon his return from Europe, I am told he submitted an expense account that included a charge and explanation that became legendary. Boat: $10,000.

But fear of flying was just a piece of his psyche on display for colleagues, who would come to think of him as beset by demons. I used to see it unravel whenever the summer sky would blacken, the way he would scurry to the basement for cover at the sign of lightning. Down there he would stay, the blood gone from his face, hands atremble. Going to the doctor was also out of the question for fear of hearing that he had cancer, and he simply could not bring himself to attend a funeral – including his own father’s. But as a young boy, none of this appeared strange to me. Nor did it seem curious that he was juggling two lives that very seldom intersected: One in Baltimore, where I lived with my mother and two younger sisters; and the other in New York, where he constructed a world disconnected from the four of us. I simply looked forward to his appearance back home: A slam of the cab door, footsteps up the walk, and there he would be, his bag spilling over with the New York papers and perhaps the typescript of a story he just completed.

“Here,” he would say, handing the piece to me as he poured himself a J&B. “See what you think of this.”

I would later hand it back to him and say, “Really good. Is it running soon?”

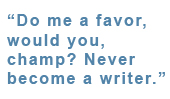

“Couple of weeks,” he said. He poured himself another then said, “Do me a favor, would you, champ?”

“What is it?”

“Never become a writer.”

“Why?”

He sighed and said, “It changes you.”

Even then I knew he drank too hard. As a teenager, I would sit up with him at the dining room as he dissolved into disjointed soliloquy. In other settings he would become abrasive, and I have been told stories of how combative he could be. For years a story has been told how he and Norman Mailer once exchanged blows at a Manhattan cocktail party, which Dad years later described in an interview with Philadelphia Magazine: “He made some uncalled for remark and then head-butted me. It became a full-scale battle. While we were on the floor, he bit my arm. Jesus. It was one of those things.” Colleague Bud Shrake told me Dad even challenged Laguerre at the bar one evening: “I remember Mark standing there and telling Andre, ‘Get off your stool, fatty, and I’ll knock you on your ass.’ Andre just looked at me and a few others and said, ‘Would you please get him out of here?’” Shrake says Dad expressed profound remorse the following day — he always did. He would shake his head and ask, “Did I really do that?”

Edgy gloom engulfed Dad when Laguerre was forced into retirement in early 1974. Says Ray Cave, an executive editor under new editor Roy Terrell: “Mark simply could not adjust.” With the safe harbor that Laguerre had provided him gone, the panic disorder that had plagued Dad since his young adulthood had begun weighing in again, striking him at random and leaving him reeling with rubbery legs, lightheadedness, cold sweats, and nausea. Years later he would describe these episodes in an essay for Men’s Health: “The overall feeling is that you are going to die, instantly – not tomorrow, right now.” A psychiatrist could have helped with this, but his fear of doctors coupled with what he called the “embarrassment of being looked upon as a blazing neurotic,” propelled him deeper into the embrace of alcohol, which only caused his symptoms “to rebound more fiercely the next day.” Editors who admired him would come to regard him as unreliable, understandably so given the fact that his ever worsening terror of flying rendered him incapable of accepting two events for which he had been slotted: The Evil Knievel canyon jump in Idaho and Ali-George Foreman in Africa.

But he had to go to Manila for Ali-Frazier III. “It was a war getting him over there,” says Cave, who remembers that he and Pat Ryan were perpetually waging a rear guard action in defense of Dad. “You always had to account for his eccentricities, and say to the people who were bothered by him: ‘Shut up!’” Cave remembers Terrell had “every conceivable feeling that it was a really bad idea to send Mark to Manila,” but Cave persuaded him otherwise, in part because he would be sitting in that week as managing editor while Terrell was on vacation. Says Cave: “I had a great deal at stake in that issue.” So Dad gulped down some tranquilizers and flew to Manila on the same plane with Ali, who would slip into the row behind him and rattle the back of his seat, intoning: “Ali and Mark Kram, we’re going to die, die, you hear!” George Plimpton – who had stepped in to cover Ali-Foreman – noted in his book Shadowbox that the trip was so traumatic for Dad that “all that was left of him to unload in Manila were a few flakes of dandruff.”

People have told me that they can remember where they were when they read his coverage of the “The Thrilla in Manila.” I only remember that I was at the University of Maryland, unaware that, on the other side of the world, Dad had become romantically involved with a young woman who later became his second wife. But that did not prevent him from doing his job: His six-page advance included a Q&A with Philippines President Ferdinand Marcos. From what Dad later told me, he then attended the “Thrilla,” supplemented his own reporting with the aid of Newsweek correspondent Peter Bonventre and others, downed some more tranquilizers, and flew back to New York. There, he handed in a story that Cave played with photographs by Neil Leifer across eight pages, which opened with stirring side-by-side head shots of the battered rivals that led perfectly into the text. The lead portrayed Ali at a dinner held in his honor at the presidential palace, then cut to Frazier in the bedroom of his villa: “The scene cannot be forgotten: this good and gallant man lying there, embodying the remains of a will never before seen in the ring, a will that had carried him far – now surely too far.’’

“Mark came through in spectacular fashion,” says Cave. “The story he did was more than splendid. He rose to the occasion. And it was the last occasion.”

I would like to be able to say that Dad did not have a hand in what followed, that he was undone by the Machiavellian creatures that have always populated SI. But that would be letting him off the hook. Living a separate life in New York had led to continual money problems — “the shorts” — he attempted to alleviate by drawing advances on his expense account, always a wink-and-nod proposition he abused. He also played the horses as if he knew what he was doing; I can just see him sitting there drawing up betting slips for some senseless exotic wager at Roosevelt Raceway. While he still delivered some very fine pieces – including a profile of Herbert Muhammad, the powerbroker behind Ali — he grew increasingly irritable as he paced the corridors, especially when Cave departed to Time and Ryan to People. By then he had also accumulated a legion of adversaries in boxing — which Sharnik calls “a stewpot in which everyone is mixing in the venom.” But Dad acted as if he were beyond scrutiny, steered by the incalculably wrongheaded belief that how he comported himself with King and others was irrelevant just so long as he remained unbiased in his copy. The only explanation I can think of is that alcohol joined with his increasing desperation to cloud his judgment.

The end came in the spring of 1977 on the heels of a crooked boxing tournament promoted by Don King, whom Dad profiled two years before for a cover story. When it was revealed that the records of some of the boxers in the draw were cooked, rumors began circulating that certain New York sports writers were “on the take” – including Dad. Sports Illustrated conducted an internal investigation and alleged three episodes of what it labeled “gross misconduct:” Dad accepted $1,100 from Ali corner man Dr. Ferdie Pacheco, one-half of his fee from Sports Illustrated for publishing excerpts from his book; he accepted $5,000 from Rocky Aoki, the Benihana founder and speed boat enthusiast Dad had profiled in March, 1976; and he utilized a researcher on that story who was not employed by Sports Illustrated. (Dad always said the payments from Pacheco and Aoki were part of book arrangements; the researcher was a young man he was then trying to help.) While there was no formal finding of a financial link with King, Dad conceded years later that he did receive payments from King for some screen work he had done; King was then looking into expanding his interests into Hollywood.

Terrell called him in. “Really a mixed up guy,” Terrell told me before his death. “I was very fond of him personally. It killed me to fire him…but it was all I could do.”

•

“Where are you going?”

“Where are you going?”

I had just parked the car and found him crossing the lawn of his apartment building in Washington to his bedroom window, which he always left open a crack for air. He stepped over a hedge, shoved the window higher and hiked himself up on the sill. Then he slipped inside.

“Get a key, would you?” I said when he opened the door for me. “You could have hurt yourself.”

“The guy at the front desk usually lets me in,” he said with a laugh. “Either that or somebody just leaves the door open.”

I looked at him and said, “In Washington?”

“What have I got to steal?”

“Jesus, you need a keeper.”

But I should not have been surprised that he did not carry a house key. He did not carry a wallet either. Whatever he had on him could be found in his trouser pockets: a few crumpled-up dollar bills, his pipe and some tobacco, a pill bottle and several packages of Sweet’N Low that he had purloined from the coffee shop. He did not own a house because living in apartments allowed him to pick up and go. Nor did he know how to drive a car – a good thing, given his drinking. Others did that for him, along with a variety of small tasks that seemed beyond him: getting books from the library, chasing down copies of his old stories. He probably had them somewhere, but they were buried beneath haphazard piles of papers, under which I inexplicably found an old car battery. I remember he used to stay up until 4 a.m. or later and not climb out of bed until 3 p.m. It was useless to even think you could reach him by telephone before then.

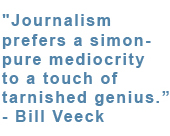

For years it seemed that Dad had disappeared. With the usual expenses that come with divorce and the demands of a second family, he eventually found himself tossed into the suburban sprawl of Staten Island, where one hungover morning he peered out the kitchen window and told me: “Another beautiful day in the Petrified Forest.” Immediately upon his dismissal from Sports Illustrated, he co-authored a book with an alleged hit man, called Blow Away, and wrote a novel, Miles to Go, on the quest to shatter the two-hour barrier in the marathon. Neither sold. Some assignments came from a talented young editor at Playboy, Rob Fleder, who had wondered what happened to him, but it was not enough to keep him from calling an old colleague and asking if he could use a connection to line him up at National Enquirer. By then he had become a sad story, which former baseball owner Bill Veeck, an old friend, commented on to Thomas Boswell in a story in Inside Sports: “I wish, just once in my life, I could write 500 words as well as that man. Journalism prefers a simon-pure mediocrity to a touch of tarnished genius.”

I remember how Dad used to seethe back then, how furious he would become at the success of others. Why him and not me? While I did not look upon him as a cruel person, it was not unusual for him to say cruel things, philosophically ruminating that “no writer should have this many children.” I remember thinking: Is he trying to tell me something? Broke, he accepted a sports columnist job for the start-up Washington Times, owned by the Reverend Sun Myung Moon. He stayed a year, grew bored, and began writing screenplays for a few thousand here and there. None were produced. Increasingly, he became obsessed with money — with not having it — and that locked him up creatively, leaving him disinclined to tug at the tiny threads that might lead to rewarding projects. For him to become interested, it had to possess the potential to bring a windfall. By now into his 50s — and looking it, with that gray, untrimmed beard — he had no patience for picking up an occasional assignment for low pay, especially from a generation of editors who would invariably ask him: “Are you using a PC or a Mac?” He still used a typewriter.

By then I had also become a writer, ignoring his advice of so long ago. I think I did it in part to draw closer to him, to get a leg up over the wall he remained behind. As a boy and into adulthood, I looked upon him with wide and pardoning eyes, even as I knew that he had behaved poorly in certain ways. But as the years passed I became worn down by his continually sour disposition, the apparent indifference he had toward my young family and our aspirations. I also became increasingly weary of our shared identity, given the fact that it carried with it a patina of shame. Occasionally, I would overhear conversations where the subject would come up, eighth-hand gossip that welled up from the psychotic delight journalists take in the troubles of others. One story that circulated even had it that the Manila piece was actually written by Bonventre, who told me with a laugh: “Nowhere near it. I gave him some cold, bare facts on the dinner at the palace, which I know he would have done for me. And he turned it into poetry.” But Dad never summoned a defense for any of it, which only underscored the validity of whatever crazy rumors bubbled up in his chaotic wake.

God, how I brooded over this.

For years.

And then one day I developed pneumonia.

I was so weakened by fever that I was unable to climb from under the covers.

Three weeks passed, and as I began feeling better, it occurred to me that I had not heard from him. I wondered how long it would take.

I gave it another week. It became a standoff.

Months elapsed before the phone finally rang one July evening.

“Where have you been? Is something wrong?”

“Nothing,” I said. “But you know, I was sick and never heard from you and well…I just wanted to see how long it would take you to pick up the phone and call.”

There was a long pause. Then he said quietly, “I know.”

Subtly, his outlook began to change for the better. Not coincidentally, he began seeing a psychiatrist and taking anti-depressants, which capped his panic attacks and allowed him to open up. Revelations began spilling from him, of fears that had preyed upon him as a boy during World War II and beyond — of young children his age crippled by polio and of anti-aircraft batteries lined up in Patterson Park in East Baltimore. He became obsessed with lightning strikes because a player on an opposing sandlot team was struck dead before his eyes by one in centerfield. And he remembered some advice he had once gotten from Laguerre, who had gotten it from Raymond Chandler years before over drinks in London: “Always try to leave three things on each page that matter to you as a writer. A word, a phrase, a line of dialogue, an observation of character. By the end of a story, these tracks of craft will lead to quality.” I remember thinking what an education our conversations had become.

Wild tigers stalked him during his sleep, yet in the light of day he gradually gained stronger footing. Not to say that he stopped bitching — especially when his assignments dried up — but he began showing up in places that he once would have avoided. When my grandmother died, we attended the funeral and later sat at the now-abandoned house on Hudson Street, where he passed up a drink himself but poured one for me and slid it across the table, saying: “To better days.” He stopped by to see his brother, Gordon, then dying of cancer, and the two of them sat in the cool shade of a tree and reminisced in a way that had always been so hard for them. He became progressively less irritable with his second family, and endeavored — albeit belatedly and with some awkwardness — to begin trying to build a bridge back into the lives of his first. Cooking became a hobby for him, and it was common for him to bake pies during the holidays for the checkout ladies at the supermarket. And I remember that he was always losing his pipe, which he once looked for high and low with some noisy aggravation, only to discover it at the bottom of a simmering saucepan of chili. He had placed it on the edge of the pot and it had fallen in when he went to answer the phone.

By then he had also recovered his bearings as a writer. David Hirshey, then an editor at Esquire and long an admirer, began assigning him pieces that, if they did not solve his unending financial crisis, gave him a place to exercise his talent. Of the subjects he profiled for Esquire – including actor Marlon Brando and drug enforcement agent Michael Levine – none were better than his incisive piece on Ali, called “Great Men Die Twice,” during which he attended a blood cleansing procedure Ali underwent at a South Carolina hospital. That 1989 piece began: “There is feel of a cold offshore mist to the hospital room, a life-is-a-bitch feel, made sharp by the hostile ganglia of medical technology, plasma bags dripping, vile tubing snaking in and out of the body, blinking monitors leveling illusion, muffling existence down to a sort of digital bingo. The Champ, Muhammad Ali, lies there now…” For years Dad had struggled with a biography of Ali, piling up pages that shuttled from publisher to publisher, but only when Hirshey landed as an editor at HarperCollins did it occur to Dad to look at both Ali and Frazier.

Going back into that world was not easy for him, if only because it was the very place that so long ago had been the scene of what he now viewed as his own foolish behavior. But he had a unique understanding of both Ali and Frazier; I think he saw some of himself in both. He had an appreciation of the struggle Frazier had endured, of how he had come out of the South Carolina low country and carved an identity out of his flabby body. Far more complex was his view of Ali: Dad yielded to no one in his appreciation of his ability in the ring — and wrote that again and again — yet it irritated him that even this astonishing talent alone was not enough, that it had to be invested and elevated in ways that were to him so perplexing. The Ali he had encountered had been a flesh-and-blood figure, given the same corrosive foibles and appealing decencies as other men. And that is precisely how Dad portrayed him in Ghosts of Manila in 2001. In a comment aimed less at Ali than his chroniclers, he observed in the introduction to the book: “Of worldly significance? Well…countless hagiographers never tire of trying to persuade us that he ranked second only to Martin Luther King, but have no compelling argument with which to support that claim. Ali was no more of a social force than Frank Sinatra.” A large percentage of the reviews were glowing, even if the Ali bloc weighed in with no small degree of animus.

Going back into that world was not easy for him, if only because it was the very place that so long ago had been the scene of what he now viewed as his own foolish behavior. But he had a unique understanding of both Ali and Frazier; I think he saw some of himself in both. He had an appreciation of the struggle Frazier had endured, of how he had come out of the South Carolina low country and carved an identity out of his flabby body. Far more complex was his view of Ali: Dad yielded to no one in his appreciation of his ability in the ring — and wrote that again and again — yet it irritated him that even this astonishing talent alone was not enough, that it had to be invested and elevated in ways that were to him so perplexing. The Ali he had encountered had been a flesh-and-blood figure, given the same corrosive foibles and appealing decencies as other men. And that is precisely how Dad portrayed him in Ghosts of Manila in 2001. In a comment aimed less at Ali than his chroniclers, he observed in the introduction to the book: “Of worldly significance? Well…countless hagiographers never tire of trying to persuade us that he ranked second only to Martin Luther King, but have no compelling argument with which to support that claim. Ali was no more of a social force than Frank Sinatra.” A large percentage of the reviews were glowing, even if the Ali bloc weighed in with no small degree of animus.

So Dad had a hop in his step when we hooked up in Tennessee for Tyson-Lewis. Tyson had exploded in fury at Dad during the Playboy Interview in November 1998, saying that one point: “Please, sir, don’t take it personally. I’m a very hateful motherfucker right now…I know I’m going to blow one day.” But Dad looked upon Tyson with a certain empathy and hoped to get a closer look at him in Memphis. Better than 20 years had passed since he had been to a live boxing match, yet he slipped into gear that week just like the old days, jotting down ideas as they occurred to him on scraps of paper and jamming them into his pocket. Seated in an auxiliary press section in the upper deck at The Pyramid, he looked upon the exchanges in the far-off ring with an increasingly disinterested eye, as if he had just uncovered his plate in a fine restaurant and found a peanut butter sandwich. Back at the hotel, he entered the elevator and happened to run into Leifer, whom he had covered “The Thrilla in Manila” with and whom he had not seen since their days together at Sports Illustrated. Leifer did not recognize him until Dad finally spoke up, “Hey, Neil! Don’t you remember Mark Kram?” Embarrassed, Leifer says now, “He just looked so different from the Mark Kram I remember.”

We both had planes out the following day: I had an early one back to Philadelphia; he could not get one back to Washington until well into the evening. Increasing concern for his health had prompted me to ask him: “Should I stay with you tomorrow and catch a later flight?” He waved me off as he had earlier that week, when he blamed the suffocating heat for his difficulty breathing. I had asked if he wanted to go to a hospital and get checked out. But he said he was fine, and I wanted to believe him. As we sat by ourselves in the hotel courtyard, we puffed on cigars and talked of the plans we each had at home. He had an assignment for GQ. “Jesus, can you believe it?” he said wearily. “Sixty-nine years old. And still out there scratching.” Small bugs swarmed in the spotlights that flooded the pool area a few feet away. Both us were dripping with perspiration and thinking of going upstairs to our rooms when suddenly the sprinkler system came on. We sat there in the cooling spray. And we had a long laugh.

•

There was no book. Five days later, I got a call at 3:30 a.m. that he had died of a heart attack. Given his uneasiness with funerals, he probably would have cringed at his own. But we had one in spite of him. A friend flew in from California for it, and a group of his old high school pals drove down from Baltimore the previous evening for the wake. Near the end of the service, I had a friend read the closing passage from “A Wink at a Homely Girl,” and as the words washed over me, I pictured a young man on that deck of that freighter as it plowed out to sea, hands braced firmly on the railing as the shoreline faded before his eyes.” The New York Times carried a very kind obit. SI printed nothing.

I have had a lot of time to think of him since then, of our days together that now seem to have been so brief. A popular online sports columnist has since written, in a piece that applauded the virtues of Ghosts of Manila, that Kram should have had a better career. I think Dad probably would have agreed with him (albeit probably not in the ways that the writer supposed). But I am entirely unclear how you quantify any of this. Journalists today are judged less by their actual writing than by their presence on television; Dad did not even appear on live TV until a year before his death, when the publishers asked him to promote Ghosts of Manila. Uneasy in the advancing age of talking heads, he remained anchored in a long ago world that placed a premium on what appeared on a piece of typescript, always full of crossed out words in what would always be a forlorn search of eloquence. I am saddened that he did not feel it added up to much, because I certainly think it did, that in 40 years behind that clanking Royal that was always overdue for a new ribbon, he produced a body of work that still stands up.

I have since ended up with his papers, box upon box of folders jammed with tobacco-scented old clippings and yellow legal pads busy with notations, the bare bones of projects that always just remained good ideas. I found it interesting that one of them also contained a long list of vocabulary words that he had come across in his reading. Opening up the boxes one by one, I have come across an array of other items: snapshots of his children, the crinkled up dismissal letter from SI, and a column from the London Times that I cannot help thinking I was supposed to find. The piece concerns the funeral of the playwright John Osborne, who had apparently harbored some old grudges that his family would not forgive. Four people were forbidden entrance to the church, an act that columnist Libby Purves found inexplicable. “Who are you to presume that the glorified John still hates anybody?” Purves observed. “In the clear dawn of eternity, all things are reconciled.” That would be good. • 6 August 2007