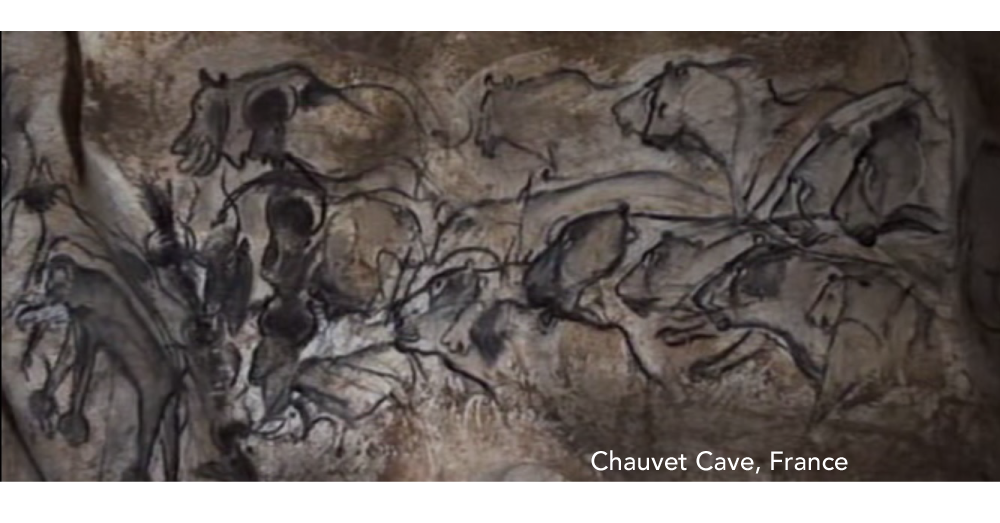

In Cave of Forgotten Dreams, the great filmmaker Werner Herzog explores Chauvet, which contains some of the most absorbing cave paintings yet discovered. They also appear to be some of the oldest, dated to 32,000 years before present. Herzog’s camera pans slowly across Chauvet’s bulbous tan walls while his crew moves handheld lights to make the many bumps and angles do a sort of shadow play. The lions, bison, horses, and rhinos outlined in black seem to flex and shift. They nuzzle, sniff, or maybe battle each other. At one point in a voiceover, Herzog says, “The strongest hint of something spiritual, some religious ceremony in the cave, is this bear skull. It has been placed dead center on the rock resembling an altar. The staging seems deliberate. The skull faces the entrance of the cave, and around it fragments of charcoal were found, potentially used as incense.” Amid the flickering beauty in this scene, that monologue got me wondering: How does he know this was a religious situation?

Well. He doesn’t. Nobody will ever know why that skull sits there. While archaeologists agree some prehistoric person did it, the reason why could be anything from a carefully-planned religious rite to a joke. That’s one of the greatest attractions — and the insidious trouble — with cave art. There is no context. Looking at it turns us loose in a wide-open playpen for the imagination where each of us fills the gaps with wishes for what should be there.

Today, most of the paleontologists, archaeologists, and tour guides who work in the caves of southern France and northern Spain follow the sober advice of Annette Laming-Emperaire, whose 1962 dissertation warned against indulging in creative theories to divine the reasons behind cave art. She also dissuaded prehistorians from using today’s hunter-gatherer cultures as models from which to extrapolate notions on what cave art means — a responsible, conservative approach.

But where’s the fun in that? Herzog didn’t make Cave of Forgotten Dreams to show what he can prove about Paleolithic hunter-gatherers. Those who obsess over ancient cultural output usually do it to find a sense of where we came from: whether or not we’re different from those who came before, and how. An active imagination is a vital tool in that effort — visualizing ourselves in other people’s circumstances, then discussing how our takes differ. My take is somewhat unique because it has always been rooted in the act of painting itself. Unlike the authors quoted in this essay who analyze cave art to understand how Paleolithic people lived, I started studying it for clues on how to make my own paintings. Appreciating these artworks as the precious leftovers of a lost way of life came later for me, after I started reading the science.

I count myself among those who (each for our own reasons) feel compelled to see cave art in person. As a painter interested in the phenomenology of everyday events, I want to champion minority ways of seeing. No painter can present a fish-eyed sample of light through a single lens as efficiently as a camera, but photography doesn’t quite match the way we see through our bodies. So instead of playing the camera’s game, I look for older, pre-photographic ways to picture the world. Tens of thousands of years ago, Europe’s earliest cultures etched and painted their way into some charming solutions for how to document a three-dimensional moving subject. They painted animals with two eyes on one side of the head, carved reliefs into the walls before painting them, and sometimes painted a kind of scan partway around an animal in so-called “twisted perspective,” a move I’ve used in my own paintings since learning of it. I thought seeing cave art live, rather than through photos and text, might yield more such lessons.

Last summer I traveled from my home in Oregon to southern France to see some of the few cave art sites still open to the public, including Le Sourcier, Combarelles, and the famous Font-de-Gaume — the only Paleolithic cave with polychrome paintings still open for regular tours. It’s situated near Les Eyzies-de-Tayac-Sireuil, a way-too-quaint village of about 800 residents literally chiseled into the cliffs of the Vézère River Valley. Railroad workers discovered five human skeletons there in 1868 along with flint tools and the bones of extinct animals under a rock shelter, or cro in the local dialect, which belonged to a Monsieur Magnon. On the heels of Darwin’s work on evolution, the geologists excavating the site realized for the first time that they were unearthing a deliberate burial by a pre-biblical people (eventually carbon dated to 28,000 years ago). Cro-Magnon made Les Eyzies a hot destination for prehistorians. Over the next several decades, explorers scoured the area’s porous cliffs for the remains of more early humans, eventually finding lots of cave art.

Thinking of ancient hunter-gatherers as religion-obsessed primitives, they began a tradition of wild speculation on scant evidence that some authors still practice. In his 2006 book The Cave Painters, history writer Gregory Curtis cites evidence in Chauvet that one child, probably about ten years old, explored it some 8,000 years after the paintings were done, the cave’s only visitor until 1994. Since the modern French explorers who found the cave left it pristine, archeologists have footprints, two handprints, and datable carbon from the child’s torch. Curtis writes, “There are no other tracks; the child was there alone. What was happening? Was it just an adventurous and inquisitive kid or was it some special ritual where for some reason a child was sent into the cave alone once every few thousand years?” He isn’t kidding. The idea that one youngster stumbled upon the cave by accident gets equal weight with the notion that a preliterate, likely nomadic, culture somehow waited thousands of years to send one special child in for a ritual that the group never repeated. That’s a profoundly silly speculation, but nobody can prove it didn’t happen that way.

Paleobiologist R. Dale Guthrie offers an Occam’s razor antidote to this way of thinking. He asks readers to imagine all the cultural expression in this area thousands of years ago: dance, cooking, music, storytelling. Some small portion of that was graphic — woodworking, clothing, body decoration — and some tiny bit of that, especially stone tools or fired clay, might last thousands of years under the right conditions, say as part of a burial or in a cave whose entrance conveniently collapses not long after the paintings dried (which was the case at Lascaux). Visiting these caves today, we’re touring images that have lasted against crushingly powerful odds. “Art inside caves was simply much more likely to be preserved,” Guthrie writes, adding, “had early researchers of cave art better understood this, they would not have sought elaborate scenarios to explain why Paleolithic peoples placed their art back in these remote spots.”

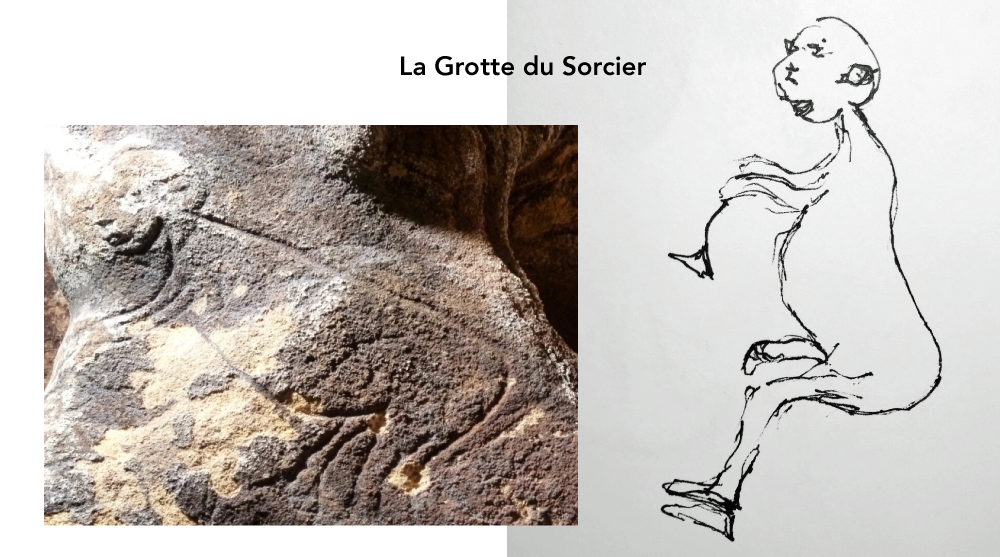

That last line is an attack on the likes of Abbé André Glory, a priest and archeologist, who explored and named La Grotte du Sorcier (Cave of the Sorcerer) in the 1950s. That cave, the first I visited in the area, still embraces its wizardy brand name, featuring a modern statue out front of a spellbound shaman with antlers on his head. Nothing inside this small cave — decorated mainly with horses and abstract shapes — suggests sorcery except an etching in the ceiling of a human with a big belly and a large penis. What looked to Father Glory like a powerful religious man looked to me like a happy baby.

Certain prominent researchers still share Glory’s view, including Jean Clottes, the former General Inspector for Archeology at the French Ministry of Culture. His most recent book, Pourquoi l’art préhistorique? — translated in 2016 as What Is Paleolithic Art? — interprets the caves as sacred places where people believed the worlds of the living and dead could mingle. He interprets the many negative stencils where visitors chewed up pigments and spit them over their hands as representations of attempts to contact the spirit world, as if certain caves had the qualities of Jerusalem’s Wailing Wall.

Bucking that speculative tradition, Guthrie is the first scholar I read who claims most cave art was likely graffiti done by children. He stakes his claim on the conjecture that the way people act now approximates how our ancestors behaved. His 2005 book The Nature of Paleolithic Art presents 500 pages of drawings, graphs, and tables that show, for instance, contemporary rates of skateboard and rock climbing injuries by demographic, which verify that young males are the most likely group to be doing risky things like crawling into caves. According to this theory, testosterone and pack mentality drove young males to venture deep underground for the fun of it. While they daydreamed about taking down big game or joked about which girl they liked, they scribbled their thoughts onto the walls around them in a feedback loop where adolescent fantasy led to images that further fueled fantasy. For Guthrie, all but the most sophisticated cave paintings are the equivalent of a delinquent student’s scratches on a bathroom wall. He writes, “Several authors have suggested parallels between the art of children and the art of ‘primitive’ people. I propose a simpler explanation: much ‘childlike’ ancient art is probably children’s art.” This quotidian lens illuminates other cave art mysteries for Guthrie, sometimes without evidence to back them up. A proficient hunter himself, he suggests, “Certain enigmatic man-beast figures in Paleolithic art may in fact be depictions of hunting disguises.”

For a moment while I entered Font de Gaume, Guthrie’s graffiti idea loomed large in my mind for the simple fact that many of the 15,000-year-old multicolored paintings in that cave had been etched over in newer graffiti from 19th-century explorers who didn’t know what treasures they were scratching into. How often did that kind of tagging spree happen, say, 14,000 years ago?

As part of his boys-will-be-boys proof, Guthrie photocopied the hands of hundreds of students in Fairbanks, Alaska, measured them each in 13 places, and compared that data to cave art handprints. He found most cave painters were males under age 18. Other researchers, doing similar studies of those handprints, have come to essentially the opposite conclusion. Examining the relative lengths of fingers in hand stencils from eight caves in France and Spain in 2013, archeologist Dean Snow found that 75 percent of the painters were women. Read side-by-side like this, cave painting studies often work together to squash knowledge back down into conjecture.

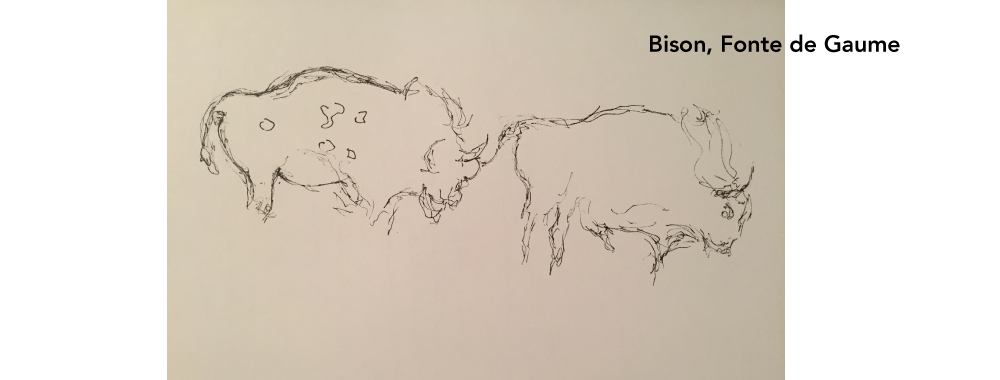

To keep the caves from succumbing to the carbon dioxide exhaled by visitors and the microbes attached to their shoes, the French Monuments Commission strictly limits tours by season, duration, and number of visitors. For reasons not entirely clear, tour guides also forbid cameras and voice recorders in these caves. However, each time I asked, they gave enthusiastic permission for me to use my pen and sketchpad. In Font de Gaume, with only a precious half hour inside, I immersed myself in drawing while the guide shuffled me and about a dozen other tourists through the various chambers. Lit mainly by her handheld lamp, clusters of animals emerged from dense shadows, some painted onto the chamber’s natural curves. In other areas, the walls seemed to have been scraped flat before the paintings were made. Sophisticated craftsmen indeed — or craftswomen. While sketching these paintings, I was surprised by how faint many of them appeared, ghosts of their former colorful glory. A few paintings, protected by layers of luminescent calcite, still shimmered in bold blacks, browns, and oranges, giving a better idea of what the rest once looked like, which magnified the sense of fragility. Those precious pigments have remained fixed to the walls for 15,000 years thanks to a naturally narrow crease in the cave 50 meters in, which protected the pictures from the shifts in moisture and temperature outside. As we squeezed through one by one, the guide referred to this gap as the Rubicon, a cute reference to the line of demarcation that Julius Caesar boldly crossed 13,000 years or so after these painters crossed theirs.

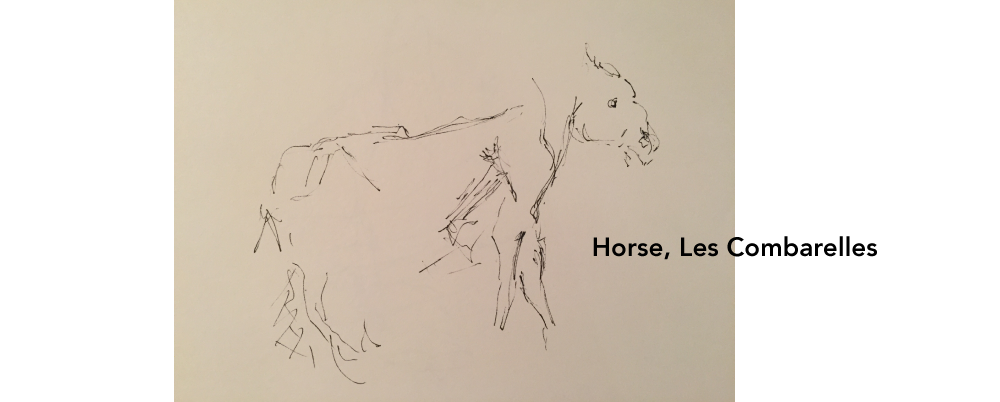

Just up the road, the deepest cave I toured, Les Combarelles, wends 230 meters into a limestone bluff and stays about hallway width the whole way, filled with 600 etchings of abstract shapes, sex organs, and big mammals. Many of the animals’ proportions — the relative sizes of heads, legs, rumps — seemed accurate as I followed the contours with my pen, as if they had been chiseled from live models.

One viewer’s art is another’s scientific record, and some paleontologists actually use cave images to study extinct animal species. The animals sit, run, copulate, and perform myriad other behaviors we can verify today in their descendants. So when a Paleolithic painting shows, say, a horse with stripes, archeologists tend to believe the species once had stripes. In his documentary, Herzog interviews Dominique Baffier, the caretaker of Chauvet. She points to a picture of a male cave lion as evidence that the species didn’t have manes. Whatever else Paleolithic painters were up to, they apparently paid serious enough attention to the animals around them and practiced drawing them enough that they could conjure those memories in the deep dark recesses.

Authors often describe feeling disoriented underground, surrounded by darkness and old earth smells. Traffic and bird noise stay outside, replaced by low voices, shuffling feet, and the occasional drip-plop echo. The world gets small, and that contributes to how we receive the images.

Drawing with my view of the walls and my paper subject to the whim of a tour guide’s flashlight, I noticed two overwhelming sensations. The first felt like, “Now, right now.” My time in each cave flew by as I flipped sketchbook pages, quietly negotiated for position among other tourists and let muscle memory take my pen over the paper. The second sensation grew as I visited more caves, drawing copies of these relics from a culture long gone. I decided I was a receiver picking up faint communication across mindboggling distance, a little like someone on another planet recording a distorted radio signal from earth thousands of years from now. But this was embodied reception, taking in the gestures of people completely foreign but built like me, who probably used their bodies a lot like me at the moment they were drawing. I could stretch my arms and feel why a given bison painting was this tall and its head this far off the floor. I could stand where the painter(s) must have stood to make all the gestures they would need with sticks, fingers, maybe a brush or rag.

After visiting Chauvet, the British Museum’s Jill Cook expressed her appreciation of the paintings in the way many arts professionals do, by declaring them modern: “So many elements of 20th-century art are present in these caves. There are even aspects of installation art there.” Some researchers support her point of view, arguing that contemporary abstract art is a language we can use to decipher certain mysterious cave marks, such as groups of parallel lines in triangular or rectangular patterns called “tectiforms.” Pointing out that Rouffignac cave has pictures of horses “structurally of similar design” to enigmatic engravings in other caves, Christine Desdemaines-Hugon asks, “Could the tectiform signs in the caves be horses in disguise?”

Ellen Dissanayake, whose research combines art history and evolutionary biology, believes ancient people probably didn’t think of a picture they made as art — that is, as an object or event celebrated not for its utility or religious power but for its beauty or ability to enrich the culture. Only in late 18th-century Europe did the word “art” begin meaning something other than “craft” or “skill.” From this point of view, what we think of as ancient art is part of a continuity of human practice that includes aesthetic adornment of all kinds. A fringed coat, a well-cut side of meat, and a painting are all pleasing to the senses, worthy of the extra effort put into them. Dissanayake calls it “making special.” Carving a deer or horse on a spear-thrower would have fused the aesthetic with the functional, intimately connecting an image to someone’s effort to get food. I find all this exciting to think about, but reading Dissanayake’s work on spear-throwers doesn’t help me understand who made those cave walls special or why.

After discussing her Chauvet visit in art terms, Cook shifts gears and recalls the sight of a small handprint high on the wall. She infers that a child was lifted to make a mark there. That moment of imagination sparks a connection across the years that “makes us understand that we’re dealing with people like ourselves that have similar feelings to us. And although they lived in a different way, some of the things that we experience within that cave and looking at those pictures is likely to be similar to what they were feeling.” I think she’s onto something here. The reason to see cave art lies somewhere in that sensation of common experience. Perhaps asking historical questions misses the point.

I didn’t come away with any exciting new rules to apply to my own studio work, but I found that these tours did change how I thought about Paleolithic painters. I had wanted to use a camera and voice recorder to document what I found underground. When denied that chance, drawing allowed me to follow their marks with my own pen — like an art student copying a portrait in a museum. In a non-narrative, embodied way, I started believing that through small, fleeting moments, I understood these people as painters if not as hunters, parents, worshippers, or bored teenagers. Quickly it occurred to me that I was becoming like the authors quoted above, another in a long line of those who go in, feel some connection laced with awe, then spend a long time trying to describe it. •

Photos courtesy of author. Feature image created by Emily Anderson.