She was a 14-pound lab-hound mix rescued with her siblings from a cardboard box on the side of the road in Kentucky. She was lanky and floppy, with big paws and ears she’d eventually grow into. When my husband picked her up and cradled her against his chest, she looked up at him and licked his chin, like she already knew she was ours. We called her Penelope Chews — Penny for short.

I was told getting a dog would be my gateway drug to wanting a baby. There are the obvious joys: When we get home from work, her tail wags furiously and she darts from my husband back to me, splitting her affection equally, pressing her body against our legs and turning her face up toward us, so grateful we have returned to her. When my husband and I take her for a run, she grabs the leash in her mouth to slow him down because I’ve fallen behind. When her velvet ears shift back on her head like a sail adjusting to the wind, or perk up into silky quotation marks, framing what I imagine to be thoughts of, “BONE!” “TREAT!” SQUIRREL!” When the light hits her sleepy eyes, making them into yellow wolf-like slits. When she circles the space next to me on the couch and drops into a tired pile against my thigh.

But the experience can also act as a deterrent.

At the risk of sounding like a monster, there have been days at a time when I didn’t particularly like my dog. I always loved her, of course. I just didn’t like her. Like when she lunged so hard at a squirrel that I tripped over the curb. When she dove for a scrap of paper blowing in the wind while I was tying her poop bag and the contents upended, spilling out like filthy confetti. When she jumped on me and her claws ripped through my new yoga pants. When she eats our neighbor dog’s poop, which sometimes gives her parasites that require medication. When I had to wrestle a detached squirrel tail from her clamped jaws. When, at the beach, a man reached into his front pocket for a treat for his own dog and Penny charged him, her front paws propelling so precisely into his crotch it was as if his groin had a target on it.

In these exasperating cases, I still saw the parallels to parenting; this time though, it wasn’t the joy I experienced. It was an insight into the perils of being constantly liable for another being — a being that was entirely out of your control. A being who was bound to exasperate you, and disappoint you. And I worried: if I was aggravated by simple dog ownership, how would I fare when the stakes were far higher?

•

My mother is a pleasant person now. She talks to our pets in high-pitched voices as if they understand English and saves them the bones from our dinner meat, spoiling them in a very grandmotherly way. She cuts her own hair, does Zumba videos in her underwear, and is tickled by bathroom humor and slapstick. She is a very pleasant person.

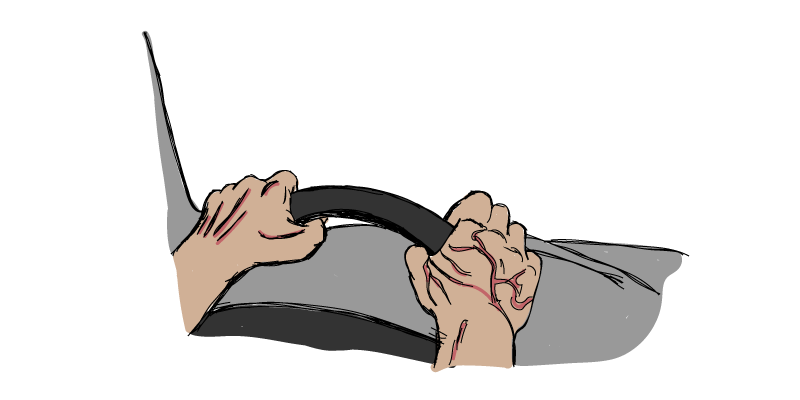

But I remember her unhappy, hair braided tightly down her neck, lines carved deeply between her eyebrows, and face pinched into a beak. For almost two decades, she was in a constant state of restlessness, my father’s holey socks pulled over her hands like mittens — her dusting tools. Or scrubbing a bathtub, her back hunched, sweat glistening on her forehead. Or heaving a shovel into the earth, dirt streaking her cheek. Or dicing onions, garlic, carrots, and celery in a hot kitchen. Or butterflying chicken breasts for cutlets. Or gripping the steering wheel while glaring at the road ahead as if it had wronged her, taking bumps at such speeds our asses momentarily floated above the seats.

How could she have been happy? It was no way to live. She was responsible for cleaning a five-bedroom house, managing its two acres: weeding, planting, mulching, watering, mowing; cooking dinner and putting it away; grocery shopping; buying us new clothes and returning what we rejected; dropping us off at school, baseball, rugby, wrestling, choir practice, youth group, a friend’s house, and then picking us up. She was our unpaid chef, cleaning lady, and shuttle service: menial work for a licensed dental hygienist, a smart woman, all for the sake of three pudgy children who were largely lazy and unappreciative of the cushy life in the suburbs she and my father had worked so hard to leave Queens and provide.

I’m sure there were moments of joy. Perhaps we even teased youthful silliness out of her — goofy physicality or sing-song voices — the way Penny teases youthful silliness from me, with games of chase and wrestling. But, as a survival mechanism, our brains are wired to retain fear over happiness, capturing and holding agitated experiences like a photographer snapping a shutter button over and over again. So I don’t remember the joyful moments as vividly.

She cried for help. She attempted delegating. She tried paying us an allowance. She made a list of rotating chores and passed out assignments. She played good cop by painting a picture of our family as a commune, an intimate network that should share responsibilities. Like hippies! We didn’t buy it. She played bad cop by yelling. Punishing. And then yelling louder. Her bad moods were severe and evident. She said ugly things. Hurtful things. This isn’t the life I wanted. I used to be a nice person. A fun person. Now I’m a slave. I wish I could take your father with me and just run away.

And we were afraid of her, afraid of the anger she generated that hovered over our house like a storm cloud. We felt its electricity in the air. It threatened. It crackled. But we acted as if we were helpless in dissipating her anger, that we couldn’t appease it or even prevent it. We stared back at her dumbly from our perches on the couch. We said stupid things. Infuriating things. If you wanted help, why didn’t you just ask for it? I will, but not now, after the show. I don’t know how to empty the garbage.

We made demands as if we weren’t a collection of powerless little shits. What’s for dinner? Ugh, I don’t like that. Can’t we have something else? I need to go to Amy’s house. Now. Why not? Just drive me; I don’t want to ride my bike. I need new clothes. Jeans. But I don’t like those jeans. Because they’re old. No one wears jeans like that anymore. I don’t want them from Bobs. I want them from a cool place. I don’t know, like American Eagle. Can I take voice lessons? Why not? But I hate the piano. Well, I didn’t ask you to buy it. I didn’t ask to be part of this family. Having children was your decision, not mine.

So, how could she have been happy?

And in her position, how could I be?

•

Even with only a puppy to care for, I’ve already seen versions of my unhappy mother rise up from beneath my skin.

One evening, friends were coming over for dinner, so Phil showered while I cooked. As I assembled a salad, Penny sauntered over, made eye contact with me, and held it while she squatted and, despite my discouraging and wild gestures toward the door, peed on the rug.

There was something about her gaze that made me think it wasn’t an accident.

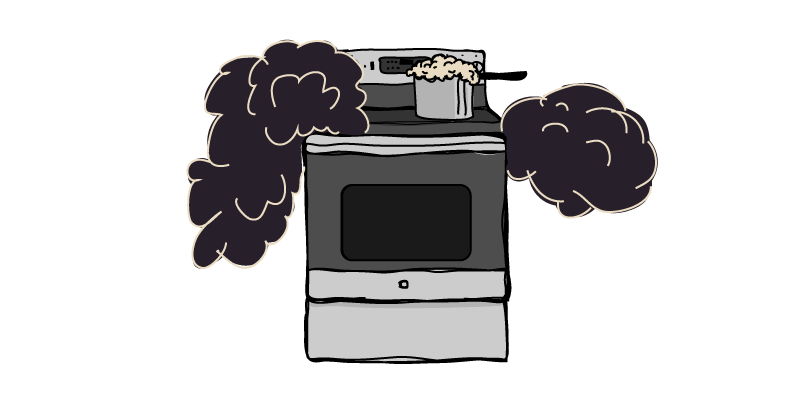

I sighed audibly and, as I knelt to retrieve rug cleaner from beneath the sink, I heard the sizzle of the rice water boil over on the stove. I spun around to take the pot off the burner, and Penny trotted right through the dark spot of her urine, tracking it into the living room. I shooed her away and blotted up the mess with a paper towel. Then I smelled something charring. The Brussels sprouts were under the oven broiler! I leaped into the kitchen and Penny scurried back and began tearing up the soiled towels and scattering them around the apartment.

Irritation simmered in my blood. It made my hands shake. Why did she have to pee right then? Why was Phil taking so long in the shower? Why was it all left to me?

I grabbed her by the scruff and scolded her through gritted teeth. “No!” Her eyes followed me, but the rest of her body didn’t respond. She was only seven months old and already she appeared bored of my discipline, unmoved. How would she respond after a couple years? How would a child react after a decade or more? Impatience, it seemed, was ineffective. Not to mention unpleasant.

•

Phil, in many ways, is my natural foil. He has the patience I would require a bottle of wine to emulate. And he adores Penny; I often catch him staring at her, dreamily, from across the room. And at least once a day, he’ll pepper our conversation with one of these rhetorical questions: Isn’t she the best? Isn’t she just the cutest pup in the world? Isn’t she the greatest thing that ever happened to us? Wasn’t she the most beautiful dog on the beach today? Doesn’t she just make your heart explode with love? Don’t you just want to squeeze her?

Come on, get in on this. Squeeze her!

Perhaps the kindest, most generous thing Phil has done for me over the course of our seven-year relationship is to take over the morning dog duties. Penny jumps up and stands over us in bed at around six in the morning, gawking down at us, completely alert, her tiger-eye irises appearing like a set of black marbles in the dark. While my instinct is to shove her off the bed and bark, “Go away, you dumb dog. Come back in two hours,” Phil scratches her ear and coos, “Morning, you little scamp.”

One dawn last month, he slipped out of the covers and followed her into the living room. Then I heard, “Oh man,” his voice falling with disappointment.

I pushed myself up in bed, squinted, and called out, “What happened?”

What had happened was he’d spotted a pile of gray cloth by the back door and had assumed it was his Irish flat cap, mangled by his precious little scamp.

Phil doesn’t value many material goods in this world; he owns only a handful of t-shirts and wears each days at a time before washing it, and when he acquires a new one (either as a gift or a hand-me-down from one of our brothers), he takes a veteran out of rotation. He’d probably be amenable to donating all of his possessions to the needy, save for his electric guitar, pocket watch, wedding ring, utility knife, and his Irish flat cap.

So, if Penny had destroyed his hat, it would have been a big deal. To me, anyway.

Phil’s tone lilted back up. “Never mind. It’s just a wool sock. I thought it was my hat. But don’t worry. Either way, I had forgiven her as soon as I saw it.”

He thought she had chewed up one of his favorite things, and he’d forgiven her instantly.

I’m so envious of his patience, his tolerance. But I don’t want to be because it doubles my crime. Now I’m not only an impatient person, I’m an impatient jealous person.

Seeing one of Phil’s strengths at work should bolster my confidence in our ability to parent, but it only makes me feel more insecure. I can see how he’ll flourish. Our future children will draw on our walls, scream in the car, throw soggy goldfish in our hair, cross their arms over their chest and refuse more broccoli, and while I’m clenching my fists, trembling, with tears pricking my eyes, Phil will remain unruffled. He’ll level his stare and coax them into doing the right thing. As a parent, I will fall short, but he’ll be gentle.

He’ll forgive them instantly.

•

Recently, there was a week in which Penny was being an especially disobedient little beast. She was pulling on walks, ignoring my commands, jumping, barking, and eating anything in our backyard she could fit in her mouth: grass, dirt, flowers, twigs, all varieties of animal poop, and a clump of unknown material that caused her to be sick for days. We just weren’t jiving, and I was visibly displeased, slower to play and petting her cordially rather than smothering her with love. It saddened Phil to see me give her the cold shoulder. He asked, “Have you forgiven Penny yet? Do you love her again?” And I’d answered, “No, not yet,” and we were both only partially kidding.

Then one afternoon, while Penny was sniffing around the backyard of our apartment complex, clipped into her lead, she wrapped herself around the pole of a poop bag dispenser. When she realized she was trapped, she panicked. She darted the wrong way around the pole, tying herself up even tighter. Then she faced her enemy, braced her front paws against the dirt, and yanked her neck back over and over again, trying desperately to free herself, her eyes wide with terror, her hackles raised like crow feathers.

I threw open the sliding glass door and dashed across the muddy grass. “It’s okay, Penny. You’re okay,” I said reassuringly.

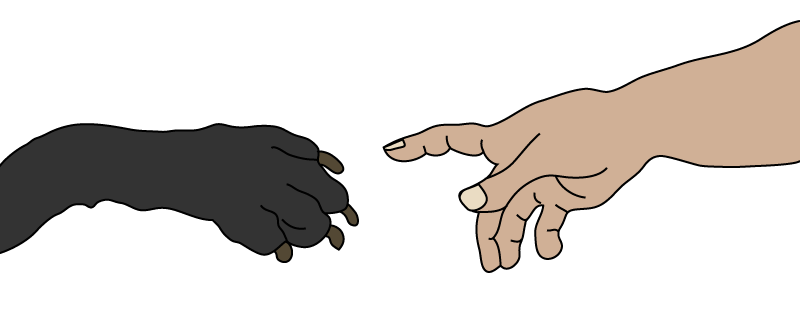

When she saw me running toward her, she stilled, confident I could help her — as if recognizing me as the one who takes care of her.

Her look of gratitude stirred me. It’s a wonder, no small miracle, that a creature of a different species, one who doesn’t look like me, act like me, communicate like me, one who was involuntarily thrust into my home, could trust me so quickly and so completely, could love me, miss me, rely on me, could consider itself part of my pack.

I freed her from the lead. Inside, I sat on the floor of the apartment and pulled her against me. She let herself be guided, dropping her weight onto my body. I stroked the coarse fur of her back. Only then did I realize my socks were soaking wet, ruined, and that my heart was pounding.

Her distress had been so upsetting. I’d forgiven her instantly.

•

Penny and I have been in sync for the last month or so. She waits for me outside the bathroom and ensures, while we lounge, that she’s always touching me, even if just by an extended paw. Our connection has deepened; I feel bonded to her.

But I worry I love her better now simply because she’s easier to love. Because she’s older, almost a year now, and is better behaved. But it isn’t enough to love someone when she’s being good, or because she’s being affectionate. With children, I know that won’t be enough; they often aren’t good, and they often show you not affection but disdain. And that’s fine; they shouldn’t have to always be good to earn your favor. And you shouldn’t love someone just because they love you.

And yet, when I open the bathroom door to find Penny on the other side, eyes rounded, waiting for me, my heart swells. “Good girl,” I say. “Good girl.”

•

My mother is happiest now when she is with my brothers and me. She loves being a parent, present tense. If I asked my mother if she enjoyed being a parent, past tense, I think her answer would be sometimes. If I asked her if it was worth the irritation, the exasperation, the occasional despair, I know her answer would be yes.

•

Penny looks like a stuffed animal, something so divine it must have been manufactured, like those black lab puppies with red ribbons around their necks that children lift from boxes on Christmas morning. Sometimes the sight of her inflates me, and I understand Phil’s fervent love. And I don’t mind that her hair finds its way everywhere: into the keys of my laptop, the bathroom sink, my coffee. Or that I have to handle turds on a daily basis with only a thin layer of plastic separating them from my skin, which isn’t enough to conceal their warmth. Or that she beheaded my tulips. Or that I’ve become as committed to dog walking as the United States Postal Service is to mail delivery: Neither snow nor rain nor heat nor gloom of night stays this walker from the swift completion of her appointed round.

Because Penny is worth it.

•

We’ve been pretty fortunate on the destructive-chewing front. The only item of value Penny destroyed was a paperback book, which she pulled from the coffee table and systematically shredded into pieces. But even then I couldn’t be mad. The book was Cesar Milan’s How To Raise the Perfect Dog.

I like to the think she got her sense of irony from me. •

All images created by Emily Anderson.