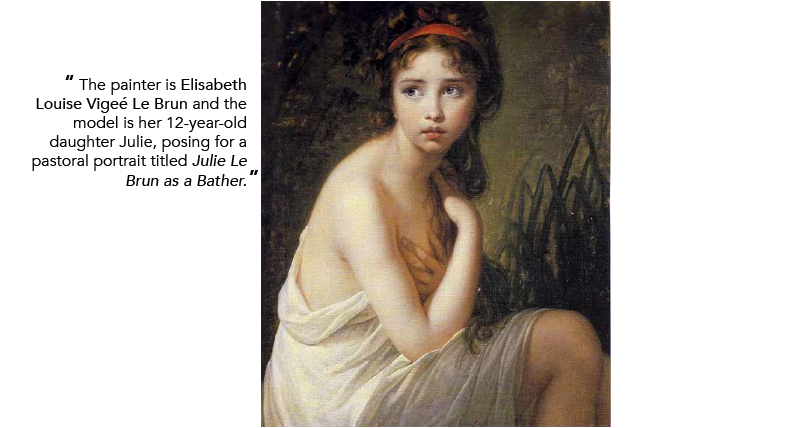

No one would dream of painting such a picture now. A pubescent girl, half-draped in a Greek tunic and preparing for a bath in a reedy pool, covers her breast and turns her head as if surprised by an intruder. And though the pose may be based on classical precedents of “Susanna and the Elders,” this is unquestionably a real girl showing real discomfort. The male gaze has never seemed so possessive — except that it’s not a male gaze, it’s a female gaze, and a mother’s gaze at that. The painter is Elisabeth Louise Vigeé Le Brun, and the model is her 12-year-old daughter, Julie, posing for a pastoral portrait titled “Julie Le Brun as a Bather.” The possessiveness and the discomfort seem uncontrived because the mother/painter was rightly concerned for the happiness and security of her much-loved only child, and the daughter/sitter would have had to feel discomfort, as any normally restless 12-year-old would, holding an unnatural pose in a drafty studio for as long as it took to complete a highly finished portrait commission in 1792.

Discomforting as the subject matter may be, the picture holds us because, like most of Vigée Le Brun’s best work, it marries technical finesse to revealing characterization. They’re not all this good. Among Vigée Le Brun’s 700 paintings, a fair number seem less like works of art than commercial transactions. The nobles and potentates of Europe paid her very high prices to flatter them, and she did. “On seeing themselves in the mirror of her art, her sitters must have felt that they were smarter, prettier and livelier than they had imagined,” wrote Peter Campbell in the London Review of Books. Furthermore, she was an arch-conservative in her aesthetics as well as her politics. (She professed to believe, for example, that the Russian serfs were “happy” in their servitude.) You don’t get much innovation in Vigée Le Brun. What you do get, as in the portrait of 12-year-old Julie, is something like a glimpse into the human soul.

Still, you don’t get beneath the surface if there’s no surface to get beneath. She knew all the tricks of the trade: the glazes carefully built up, the spare-but-telling accents of color (as in the crimson of Julie’s hair band), the dark, atmospheric background setting off a luminous foreground. But lots of portraitists could do with glazes and color and lighting what Vigée Le Brun could do; only the best could capture or suggest personality the way that she could. And if she managed to reveal (or invent) a core of humaneness in some of her most vapid aristocrats, how much more affecting are the handful of paintings she made of the person she loved most in the world: her daughter.

The coy sexuality of “Julie Le Brun as a Bather” induces squirms; it would not have in Vigée Le Brun’s contemporaries nor in the patron who commissioned it, Prince Nikolai Borisovich Yusupov, who collected the best of the best among French painters of the period, from Fragonard to David to Vigée Le Brun herself. Furthermore, a 12-year-old European girl in 1792 would have been considered on the cusp of adulthood. (The Duchess de Guiche, who sat for Vigée Le Brun several times, was married at 12.) And maybe the sexuality of the portrait isn’t so coy after all. Maybe what we have is a mother lovingly observing the emergence of her child into a young womanhood of beauty and sensuality. That the daughter seems more or less stunned by this emergence might make the picture more rather than less tender and solicitous. Julie has no idea what’s about to hit her; Louise had already been there.

In her Memoirs, Vigée Le Brun claimed that as a teenager she was stared at in streets, theaters, and other public places. That’s easy to believe, if her youthful self-portraits are any indication. The velvety complexion, the retroussé nose, the shining, intelligent eyes: Louise was a knock-out, but her beauty brought with it unwelcome complications. As a teenage prodigy, she was sometimes commissioned for portraits by successful and powerful men with designs other than aesthetic. And yet like the femme du monde that she was, or like the wise wife Elmire in Molière’s Tartuffe (“to be proficient / In keeping men at bay is quite sufficient”), she knew how to take care of herself. Nor did it hurt to have her mother in the room:

As soon as I observed any intention on their part of making sheep’s eyes at me, I would paint them looking in another direction than mine, and then, at the least movement of the pupilla, would say, “I am doing the eyes now.” This vexed them a little, of course, but my mother, who was also present, and whom I had taken into my confidence, was secretly amused.

According to her biographer, Angelica Goodden, Vigée Le Brun “felt that she lived in a society which women governed, subtly but absolutely, and governed through both mental and physical seductiveness.” She certainly governed her own household. Her feckless husband, the art dealer Jean Baptiste Pierre Le Brun, sponged off her earnings, spending much of the profits on his mistresses. Even before their divorce in 1794, she was essentially a single mother, overseeing the education of her daughter, supervising the servants, taking in (grudgingly) a few pupils, and rarely refusing a commission. She also found time to preside over one of the most exclusive salons in Paris. Goodden believes that Vigée Le Brun was a disastrous mother, at once over-protective and neglectful and that her intimate paintings of Julie wrapped in her mother’s arms were designed to promulgate an image of Vigée Le Brun as “more than a man-artist: she was a mother as well as a painter.”

Even discounting for the strain of paranoia that colors her late Memoirs, Vigée Le Brun was subject to vicious gossip all her life. An upstart, a harlot, a decadent, a lackey to the rich and powerful, an unfit mother: she was called all of these things, with no allowance made for the incredible effort and discipline it took for a woman from an undistinguished middle-class family who was denied by her sex the advantages of formal training to end up as the court painter (for which she might easily have been guillotined) to Marie Antoinette. Is it any wonder she might have loaded her daughter with more emotional freight than the girl could ever quite support? And though she might have had a point to prove with such pictures as Self Portrait with Her Daughter Julie (mother and daughter locked in a compositional spiral, each looking outward with expressions of rapturous sweetness), there’s no reason to consider the picture a fake. There’s such a thing as a special intimacy between mother and daughter; this is what it looks like.

Or what it looked like in 1786 for a conspicuously successful and attractive young mother of the upper classes and her obedient daughter. It wouldn’t have looked quite so cozy a few years later, when the adolescent Julie was beginning to chafe against her mother’s possessiveness. But before the inevitable breach, which never healed and which left Louise feeling that “the whole charm of my life seemed to be irretrievably destroyed,” mother and daughter had a lot of down time together in the studio. My favorite depiction of Julie is as a wide-eyed, solemn seven-year-old gazing into a mirror that she holds before her (“Julie Le Brun Looking in a Mirror”). Could anyone but a mother have painted this reverent double-portrait of radiant girlhood? Yes, given that Jean-Jacques Rousseau’s cult of childhood innocence was then at its peak and had gripped virtually the whole of French society, fathers no less than mothers. Nevertheless, that combination of highly wrought surface and unaffected feeling seems peculiar to the portraiture of Vigée Le Brun. The mirrored perspective of Julie in frontal gaze, for example, in contrast to the profile image, is deliberately and playfully impossible. But if ever a portrait seemed painted con amore, this is that portrait. Although the light beautifully heightens the emerald green of Julie’s dress, it’s the heart-stopping vulnerability of the little girl inside the dress that makes the picture.

Rousseau neglected to mention that children can be perfectly horrid; within a few years, according to the biographer Geneviève Haroche-Bouzinac, the reins of power had switched from mother to daughter. (“C’est une enfant choyée, trop choyée,” she laments. Haroche-Bouzinac is on mom’s side.) However fraught this mother-daughter relationship might have been, “Julie Le Brun Looking in a Mirror” viscerally evokes our deepest and most instinctive feelings about children: that they merit all the love and protectiveness we can possibly bestow on them; that they are not merely miniature adults but beings with achieved souls and personhood; and that little kids are unbelievably cute.

Actually, Louise did think that Julie was perfectly horrid. At any rate, when the 19-year-old girl married against her mother’s wishes the financially and socially unsuitable secretary of a theater director, Vigée Le Brun felt that “the cruel child showed not the least gratitude at what I had done for her in immolating all my wishes, hopes and dislikes.” While this drama was playing out (in Petersburg, one of many stops on the European tour undertaken by the Vigée Le Brun entourage after — just barely — escaping the Revolution), Julie posed for her mother one more time. It must have been a tense sitting. In the catalog entry for the 2016 Vigée Le Brun exhibition at the Metropolitan Museum, Paul Lang wrote that the pose of Julie as the goddess Flora (flower basket, laurel wreath, Greek tunic) would have evoked associations with the idea of a courtesan: “the artist may have been discreetly expressing all the hostility she felt toward a marriage with this Petersburg Zephyr.” In “Julie Le Brun as Flora” the model certainly displays a lot of skin, but her décolletage and naked arms are just as likely signs of an uncorseted, unashamed womanhood as of anything more sinister. Vigée Le Brun took pride in posing her female sitters, not least of all the Queen, in more natural costume and less affected toilette. And with the elegant folds of her simple tunic and frank three-quarter gaze (not to mention the fantastic still-life she balances on her head), Julie looks exactly like the kind of attractive, self-possessed young noble that Vigée Le Brun had rendered so many times in Paris and Rome and Naples and Vienna. (“No painter ever surpassed her in rendering the glow of happy young women,” wrote Germaine Greer.) What she does not look like is anyone’s daughter. No such formality or mythological trappings encumbered Louise’s portraits of the younger Julie. The little girl was, before any symbology of Purity or Devotion could be weighed upon her, a little girl. “The docile child,” wrote Haroche-Bouzinac, “had given place to a young woman of strong, peremptory character, so that Mme. Le Brun’s entourage had to warn her of what might happen with her continuing lack of authority: ‘You love your daughter so much that it’s you who obey her,’ they told her.”

Notwithstanding the maternal tenderness that Vigée Le Brun lived and painted, there wasn’t much of that left when Louise died, divorced and in poverty, in Paris at the age of 39. In the Memoirs she wrote in her 70s, Vigée Le Brun spent more time dwelling on her grief than imagining the difficulties of her daughter’s life, which she might have eased with financial support if nothing else. She seems to have transferred her motherly affections to her niece, who from 1809 tended to her aunt at the estate the latter had bought at Louveciennes. Whoever was primarily to blame, mother and daughter had done a pretty thorough job of breaking each other’s hearts.

By the time Julie died in 1819, something had died in her mother’s art. She had resettled in France ten years earlier, one of the extremely select handful of women to have gained admittance to the French Royal Academy, but her moment had passed. Only two of the works in the Metropolitan’s comprehensive retrospective dated from her last three decades. Declining to read The Hunchback of Notre Dame, the literary sensation of 1831, she said simply, “I’m not of this century.” So let’s go back to an earlier century and take a look at one more maternité, “Self Portrait with her Daughter Julie” (a` l’Antique) from 1789. It’s a` l’Antique because this time Louise has costumed herself in the customary Greek tunic, while Julie wears a more modern frock of indigo blue. Compositionally, it’s a simple pyramid, with no foreground details or fake landscape background to distract from the touchingly clumsy embrace of the mother and her nine-year-old daughter. It’s not her most complex or most bravura or most ambitious picture, but it has been beguiling the crowds at the Louvre for almost two hundred years. According to the art historian Mary D. Sheriff, this celebrated double portrait “undermines the ideal of a good mother not only by intertwining biological and cultural production, but also by showing in [its] very making and exhibition that [its] author was a working artist who could not have had the leisure to devote herself entirely to raising and educating — or even simply to bearing — her children.” Maybe. But it also shows a lot of love. •

All images courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.