It’s a bit specialized, admittedly. Nonetheless, Ben Davis’s Repertory Movie Theaters of New York City: Havens for Revivals, Indies and the Avant-Garde, 1960-1994 delivers exactly what the title promises. If you were ever dying to know what sort of programming choices distinguished the Carnegie Hall Cinema from the Bleecker Street Cinema in the 1970s, this is the book for you. But it might also be the book for you if you ever fell in love with movies and had a favorite theater or two, whether in New York or any small city or college town, to nourish that love. When I moved to New York in 1978, I fell so hard for movies that Davis’s book (hereafter RMTNYC) reads more like a lost diary from my youth than the erudite, exhaustively researched study that it is. Accordingly, what follows is less a review of the book than of my life. How can I talk about the Thalia without mentioning the movie-mad debates I had with the girl I loved and my best friend on our way to and from the screenings there? At the time, we were all grad students at Columbia, but the real education we got was in the theaters and the streets.

Davis divides his study into two sections, the “First Wave,” from 1960 to 1974, and the overlapping “Second Wave,” from 1968 to 1994. I wasn’t around for the First Wave, and even some of the Second Wave theaters (notably the Elgin, which I had heard about from older friends) had shut down by the time I arrived on the scene. Still, there were half a dozen major repertory theaters beckoning me to cut my boring classes at Columbia’s School of Library Service (later supplanted by rather less boring classes in the English Department). The nearest to hand was the Thalia, a brisk walk away on 95th Street, just off Broadway. According to Davis, the Thalia was “influential in popularizing the postwar film genre, film noir, and resurrecting the work of non-Disney cartoonists,” but what I remember most about it is not so much its “reputation for adventurous, one-of-a-kind programming” as the theater’s bizarre configuration, which sloped down and then up, so that I always felt as if I was in the long and narrow stateroom of a peculiarly listing ship. Davis reports that Molly, the dog of the owner, an “eccentric, obsessive film nerd” (the owner, not the dog), “saw every movie, and if she liked you, she sat next to you.” I remember seeing for the first time at the Thalia Cary Grant and James Mason in North by Northwest exchanging debonair insults over the suffering head of Eva Marie Saint, whose beauty had unwittingly provoked the fury of their fragile male egos; I do not remember Molly.

The Regency (1966-1987) was a few blocks further down on Broadway, on 67th Street. Larger and better-appointed than most of the other rep theaters, it exuded no picturesque squalor, and its chief programmer, Frank Rowley, had enough clout to demand the best prints from the MGM vaults, his principal source for films. In my high-minded quest for Art (or disreputably squalid entertainments), I generally avoided the Regency, which tended to musicals and Hollywood star vehicles. Prodded by the Village Voice film critic Andrew Sarris, Rowley experimented with the occasional Rossellini or Godard retrospective, but as he told Davis, “that kind of stuff . . . cleared the house.” What the regulars at the Regency really wanted, I always suspected, was to see Singin’ in the Rain for the 68th time. In those days, I disdained such gross philistinism. Now I want to see Singin’ in the Rain for the 68th time.

It was Fred Astaire and Ginger Rogers who removed the scales from my eyes. On a whim, I decided to give Top Hat & Swing Time a try one summer day. They were playing on a double bill at Carnegie Hall Cinema, but they could just as easily have screened at the Regency or the Thalia, not to mention the ever-reliable Museum of Modern Art, an institution outside the scope of RMTNYC. I therefore owe to Carnegie Hall Cinema (1973-1986) the discovery of what my parents and millions of ordinary movie-goers had always known: that if great Hollywood musicals like Top Hat & Swing Time weren’t art, nothing was. I did more than fall in love with Astaire and Rogers; I fell in love with Carnegie Hall Cinema. Apart from its studiedly French sophistication (it was, after all, housed in the Carnegie Hall building, and cappuccinos and brioches were served in the attached Café Mille Yeux), it seemed to me to combine the best of the left-of-center programming of the Thalia with the best of the right-of-center programming of the Regency. A typical program from the summer of 1975, writes Davis, consisted of:

a Jean-Luc Godard retrospective on Mondays from June 16 through August 25; a festival of Charlie Chaplin and Harry Langdon films, “Comedy Kings: Chaplin and Harry Langdon”, on Wednesdays in July; and a Yasujiro Ozu special, “Yasujiro Ozu: Selected Features,” on Wednesdays in August.

Long after I had moved to Brooklyn and had matured cinematically as well as, I hope, emotionally, I continued to frequent Carnegie Hall Cinema and delight in its eclectic mix of international cinema, old and new, silent film (with live musical accompaniment on the splendid house organ), and American genre movies. Its demise in 1986 (done in, as usual in this story, by Manhattan real estate prices) felt like a body blow.

Carnegie Hall Cinema had a sister theater in Greenwich Village run by Jackie Raynal, a filmmaker herself and one of the few women to make a sustained appearance in the generally male-dominated world of RMTNYC. (She was married to Sid Geffen, who ran Carnegie Hall Cinema, and her connection to the French Film industry informed and enriched the programming at both theaters.) The Bleecker Street Cinema was smaller and altogether more raffish than its uptown counterpart. Fortunately, Jackie Raynal liked rock and roll almost as much as I did, and one of her specialties was rock and roll movies. I have a photo of my girlfriend and me standing underneath the marquee announcing a double bill of Peter Brook’s Marat Sade and King Lear with a midnight show of Jimi Hendrix – a fairly representative sampling of the offerings at that ever-surprising venue. If the Thalia was the neighborhood theater for Columbia students, Bleecker Street was the same for the NYU crowd: a lot of Godard in both places. The last time I walked by that stretch of Bleecker Street, a chain pharmacy stood where I had once discovered Luis Buñuel and Agnès Varda. It’s probably a taquería now.

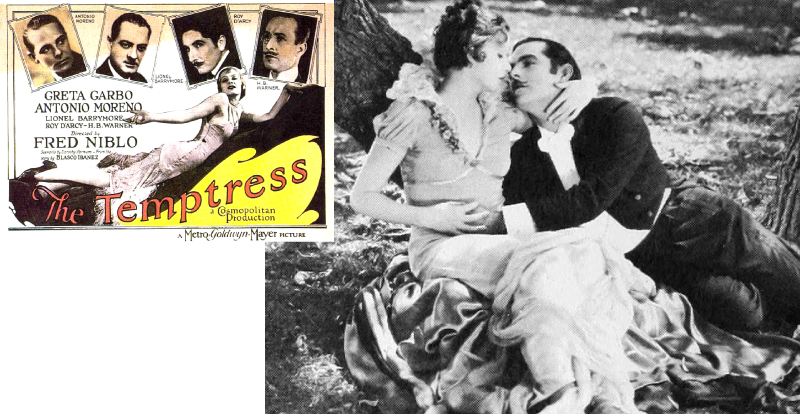

The remaining repertory theater of the Second Wave considered at some length in RMTNYC is Theater 80 St. Marks. Theater 80 was, even by the standards of bygone New York cinematic subcultures, a notably eccentric operation. In the first place, it eschewed the thematic or curatorial programming favored by its competitors and more sophisticated cineastes. At Theater 80 it was strictly a random collection of daily double features selected according to the personal taste of the owner and manager, Howard Otway. (His rationale, writes Davis, “was that he did not think one should have to wait through six weeks of mysteries if they [sic] wanted to see a comedy.”) Secondly, because there was no room in the cramped theater for a projection booth in the back, Theater 80 used rear projection from behind the screen and through a mirror, which, Davis notes, made “even a pristine print look fuzzy.” That was enough to keep me away most of the time. (Even after all these years my art house compulsiveness persists: I won’t watch a serious movie on a television or computer screen.) Furthermore, the programming at Theater 80 made the relatively staid Regency look like the last outpost of the avant-garde. At Theater 80 it was all Bette Davis (and Gloria Swanson and Ruby Keeler and Joan Crawford) all the time. The great poet W. H. Auden, who lived across the street at 77 St. Marks Place, occasionally dropped by for a Greta Garbo weepy. “My dear,” he explained, “one is not always rational.” Davis fails to mention what was obvious to me on my few forays to Theater 80: It was a very gay crowd. So aside from its importance in screening an enormous variety of Hollywood genre films, Theater 80 also played an honorable role in the gay cultural history of New York. I wish I had paid a little more attention.

For a time in the 1990s, I and other art house regulars in New York (and the whole country) were on the verge of despair. Not only had rising real estate prices shut down nearly all of the revival houses, but no one but us and Susan Sontag seemed to care. In 1996 Sontag wrote a cri de coeur for the New York Times Magazine called “The Decay of Cinema.” Well, cinema is always in a state of decay — and always managing somehow to renew itself. She did, however, put her finger on a disturbing trend:

But you hardly find anymore, at least among the young, the distinctive cinephilic love of movies that is not simply love but a certain taste in films (grounded in a vast appetite for seeing and reseeing as much as possible of Cinema’s glorious past). Cinephilia itself has come under attack, as something quaint, outmoded, snobbish.

Since then the situation has stabilized. Funky, quirky, shabby art houses with changing daily schedules of Mizoguchi and Laurel and Hardy movies are long gone, but at least in New York semi-public institutions like the Museum of Modern Art, the Film Society of Lincoln Center, and Film Forum (plus a few classy outliers like the Metrograph and the Brooklyn Academy of Music) continue to screen movies from “cinema’s glorious past” as well as showcasing new filmmakers from parts of the world previously unrepresented on American movie screens. Moreover, this cinema can be experienced in near to state-of-the-art conditions that challenge the nostalgia for the canine mascot that once roamed the isles of the Thalia. Am I the last person alive to care about Ingmar Bergman? Sometimes it feels that way, and don’t get me started on what Quentin Tarantino, who cites him as a key influence, doesn’t know about Jean-Luc Godard. At the end of RMTNYC Ben Davis places his bets on emerging “microcinemas” in Brooklyn and the Bronx. To me, they seem too esoteric and rootless to last, but I could be wrong. Anyway, I no longer despair about the “decay of cinema.” In spite of all the odds, great, life-altering films continue to be made, and they get shown in New York and Philadelphia and Los Angeles and wherever there’s a sufficient audience to support them. The life-altering film may have been made by Martin Scorsese on a budget of millions and millions of dollars or it may have been made in Senegal on a shoestring by a director I’ve never heard of. But if it hadn’t been for the late, lamented repertory movie theaters of New York City, I never would have known that a movie could alter my life. •

Feature Image by Emily Anderson, all other images courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.