From spearheads to skeletons, mummies to mastodons, caskets to ritual masks, the North’s soil has yielded thousands of clues to bygone lives. But only once have motile shadows returned from this underground realm. In 1978, during construction of a new rec center in the town of Dawson City in Canada’s Yukon, a backhoe unearthed 533 newsreels and feature films dating from 1903 to 1929, many of them thought to have been lost to time’s ravages, others previously unknown. Stored initially in the town library’s basement, they had been interred in an old gym pool that double-functioned as an ice rink. There they rested like Snow White in her crystal coffin. The pool site was part of the Dawson Amateur Athletic Association’s building, which opened in 1902 and soon after began screening films. Some of the cache’s contents played again in the rebuilt Palace Grand Theatre 15 months after their discovery, almost 50 years after their disappearance.

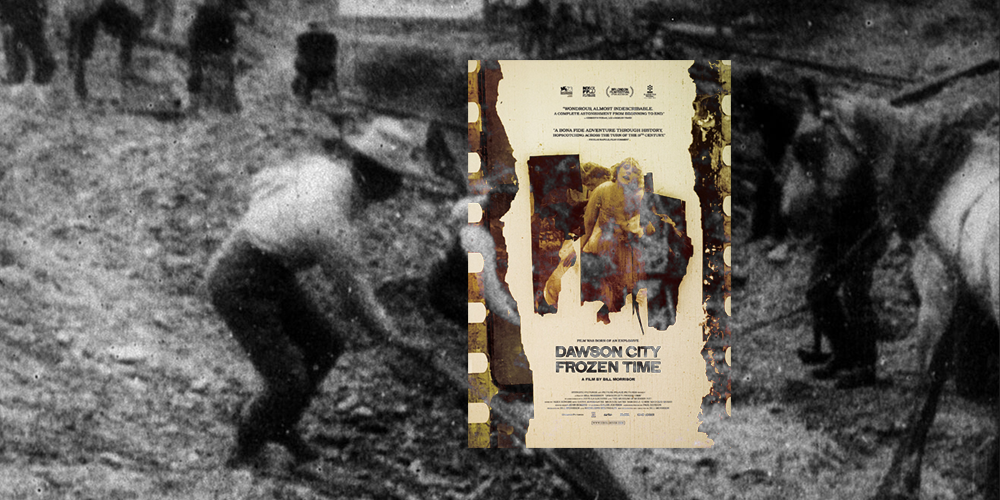

The reels, spanning the heydays of silent, black-and-white moving pictures recently, now have been given a new lease on life. The New York film director Bill Morrison — a fan of things out of fashion — artfully reassembled snippets of cinematic treasure snatched from the debris. His two-hour, largely narration-free meditation Dawson City: Frozen Time launched in 2017 to acclaim. (It is only showing in few, select theaters; it can be downloaded from iTunes.)

A subtitle five minutes in, “Film was born of an explosive,” refers to the martial origins of celluloid. The plasticized base of early films, cellulose nitrate, was used as “guncotton” in warheads and was extremely flammable. Patented in 1889, coated, light-sensitive Kodak stock not only revolutionized entertainment but in Dawson and elsewhere fed conflagrations. The business district of the timber-built Yukon hub burned every single year of its first nine. Worldwide, firestorms consumed film collections in warehouses, studios, laboratories, and theaters, including the very movie houses that screened such films in Dawson City. Sic transit Gloria Swanson!

Under sustained continental summer temperatures, cellulose nitrate releases gases prone to spontaneous combustion, turning sealed film cans into pressure cookers. Edison’s film manufacturing plant blew up in 1914; Robert J. Flaherty ignited 30,000 feet of Nanook of the North by smoking a cigarette.

Because movers and the railroad refused to ship the fickle stock which has been dredged from the permafrost and temporarily stacked in a root cellar, the Armed Forces flew the crates to Ottawa in a Hercules plane. At the capital, Library and Archives Canada preserved the unstable images. With help from the U.S. Library of Congress, staff then cataloged the entire collection, printed it onto 35mm safety film stock, and entombed it in climate-controlled vaults for the past 38 years. Morrison, who visited Whitehorse and Dawson while making his movie, obtained scans of any reel he wanted to watch.

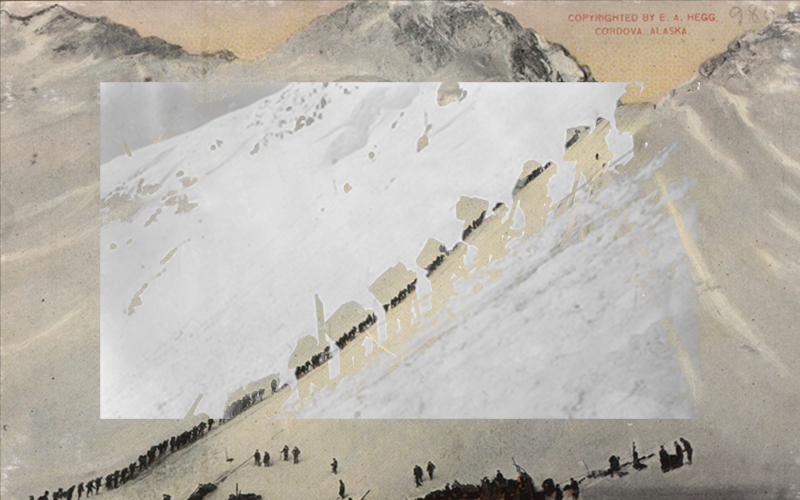

Another surprise trove added perspective to Morrison’s sprawling canvas: almost 200 photo negatives by the Swedish emigrant Eric A. Hegg. Considered valueless, they’d been insulating the walls of a Dawson City cabin until 1947, when the glass plates barely escaped becoming greenhouse panels. The prospecting Swede had followed the shifting human tide from Skagway to Dawson to Nome. His shots of men loaded like mules and stair-stepping up a 45-degree slope to the snow-choked U.S.-Canada border were copied in Chaplin’s The Gold Rush (1925) and onto Alaskan license plates. Hegg’s output also included the only surviving pictures of the infamous 1898 Palm Sunday Avalanche’s aftermath. First exhibited in a New York gallery in 1901, they caused crowds vying for a peek to riot.

Splicing in period newsreels and newspaper headlines as well as post-WWII home movies, Dawson City: Frozen Time among other things charts the transformation of the peaceful indigenous fishing camp Tr’ochëk to a boomtown surrounded by denuded land to a respectable, film-obsessed backwater — a tale partly familiar to readers of Pierre Berton’s The Klondike Fever. The highlights are all there in grainy detail: sternwheelers; dead horses; scows hammered together at Bennett Lake; seething Miles Canyon Rapids; George and Kate Shaaw Tláa Carmack; Skookum Jim, Chief Isaac, leather-faced; prostitutes’ cribs lining Paradise Alley; claims on Bonanza Creek; a dancer-turned-entrepreneur; and latecomer Robert W. Service of “Sam McGee” fame.

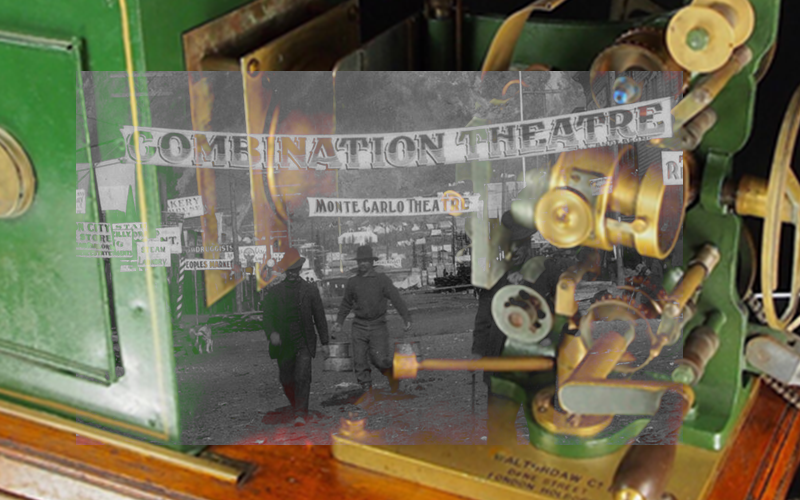

Dawson was perfectly situated to grow as a hotbed of the fledgling film industry. Founded in 1896, the same year that large-scale, commercial projection took off, it hummed with audiences eager to be entertained. Theaters such as the Orpheum or Monte Carlo distracted townspeople on long winter nights, and miners who’d never strike it rich. As the light beams from projectors pierced smoke-scented halls, men and women marveled at luminous ghosts, glimpsing worlds they’d temporarily renounced. When the Spanish-American war broke out, throngs gathered and paid to hear the newspaper articles read. Theaters such as the Orpheum or Monte Carlo distracted townspeople on long winter nights and miners who’d never strike it rich. “Good Time Girls” and impresarios walked the city’s muddy streets. Future Hollywood moguls Sid Grauman (a sometime boxing promoter) and Alexander Pantages worked in Dawson hotels. Any fortune-hunter quitting his bank job to follow the siren call north was kindred to those headed west to chase wealth or fame in the Dream Factory.

The ballooning subarctic settlement lay at the end of film distribution lines, where motion pictures often were screened only years after they had premiered. Dodging the high cost of return shipping, distribution companies charged a bank manager with keeping the films at the local library. When that ran out of storage space, cartloads of reels that could not compete with the new “talkies” were dumped among the Yukon’s grinding ice floes, cremated at the waterfront, or buried as landfill.

Hegg’s and Chaplin’s iconic depictions of miners scaling the Chilkoot Pass, antlike, mythologized Dawson and the Klondike rush. By the late 1920s, the town had developed a modest tourist industry, which cashed in on and kept alive the mystique.

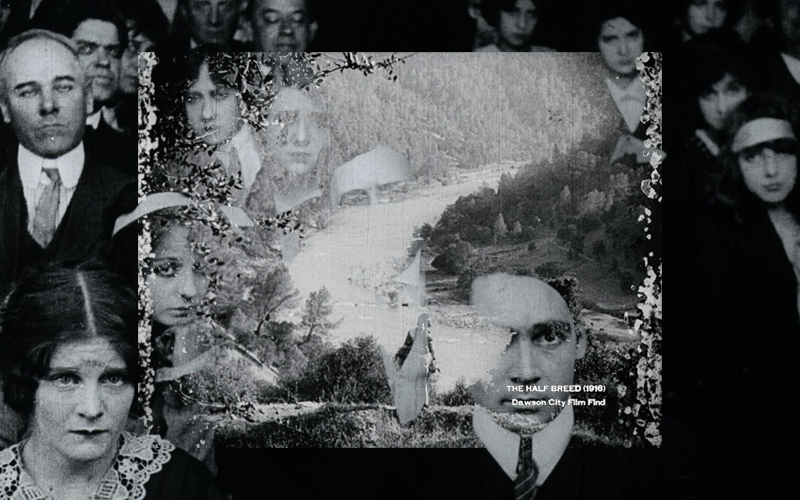

Morrison sends up equally popular tropes shared by silent films from that era with his clever edits, loops of gestures and plot devices — such as reading a letter, listening at a door, or barging unexpectedly into a room — that, followed by text cards, advanced those films’ narratives.

Used to swooping cameras, IMAX projections, and layered sound effects, modern filmmakers and audiences are much more sophisticated than their counterparts 100 years ago. We experience an immersive cinema, a kaleidoscope of fast-paced edits and minimal exposition, which can even baffle our parents’ generation. Morrison, who eschews video games, feels that they dominate today’s market, communicating to younger viewers in ways completely beyond his comprehension.

Unsurprisingly, a sense of loss and recovery informs Morrison’s approach. For the filmmaker, the history of oblivion and the obliteration of history march in lockstep. Both nourish his fascination with found, silent, black-and-white footage. Clips of Colorado miners on strike being killed by National Guardsmen and of anarchist leaders deported to Russia ensure that the labor movement’s feats, like the corporate consolidation of Yukon mines, still flicker brightly in the public’s conscience.

Trying to explain his new film’s success with audiences and critics, Morrison points out that it is, first of all, a great story, one that captivates different types of viewers, even those who are not necessarily fans of old silent flicks or of his filmmaking style. Underlying that, like some panoptic memento mori, the work speaks to a larger, universal condition: the fleeting nature of cultural memory, which resonates in these short-attention-span, blockbuster times.

“When we lose filmic record, we lose the memory that these things occurred,” this award-winning auteur insists. Film, however, has an uncanny power to resurface, which allows reexamination and re-contextualization. When Morrison first learned about the find in the late 1980s (he can’t recall exactly when), knowledge of it circulated among people interested in the medium. Now, decades later, nobody younger than him seems to have heard of this story, and most of those who have are older cinephiles connected to archival film or to Dawson.

It has been said that Americans regard good movies like Europeans regard classical music. But the shelf life of movies at best is measured in decades, not centuries. “It appears that the former swimming tank had been used in the distant past as a depository for discarded movie film,” a newspaper account from 1939 claimed. At that time, the films, after only ten years, already had slipped people’s minds. Then they started to leech from the ground after a fire destroyed the building on top.

A cut from The Salamander (1916) precedes Dawson City: Frozen Time’s final, extended scene, a potent metaphor for transience and resurrection. In it, a veiled actress gyrates ecstatically, engulfed by “flames” — lesions on film stock from water damage that occurred while these reels lay dormant. According to ancient folklore, the salamander, like the restored films, survives fire.

Morrison shunned the voiceover typical of documentaries, seeking to encourage the reflection that comes from reading factual text rather than telling audiences what these images represent. A narrator for him would break the timeworn images’ spell, distancing viewers who look with hindsight at “quaint old pictures” of characters long dead. Sigur Rós collaborator Alex Somers’ hauntingly beautiful score instead serves as a guide on this journey, providing musical backup to an unforgettable trip into a largely forgotten past. •

Feature image is Still from The Trail of ’98 (1928). Courtesy of Madeleine Molyneaux, Picture Palace Pictures with film poster for Dawson City: Frozen Time.

All images courtesy of Kino Lorber, National Archives, Vancouver Public Library, Sjur Dagestad, Dawson City Museum and Dawson City Collection, Library And Archives of Canada. Image collage and manipulation by Isabella Akhtarshenas.