I think about shame a lot. I wonder when and why I began to care so much about stuff — my body, my face, my intellectual ability. Did it start when I was bullied on the bus in kindergarten? Was it some sort of pseudo-consciousness mind trick passed down from my parents? Was it because I picked up a Seventeen magazine when I was 11? For whatever reason, I remember a lot of low and high-key shame moments from my younger years. I didn’t want to wear shorts as a preteen, because I was starting to sprout leg hair and was too embarrassed I hadn’t started to shave. Clothes shopping in high school was never fun because I couldn’t find anything to adequately fit my body. I’d enter a dressing room with a pile and leave with nothing, because (what I imagined to be) my grotesque body wouldn’t cooperate. And while I was feeling so dejected and ashamed, I rarely vocalized. For years, I assumed everybody else had figured the body out.

More than likely, these insecurities were the result of “all of the above.” These ideas as to what the body should and shouldn’t be, how I should comport myself, and the anxiety over having no knowledge as to how to manage either were no doubt filtered through the various ecosystems I existed within throughout my adolescence. It wasn’t really until graduate school in my 20s, that I began trying to re-train my brain to ignore the compulsion to care and instead think more about what worked on my terms. Whereas I once had romantic notions about the body and its possibilities, I began to realize how gross it all was, and in turn, how ridiculous it was to care so much about how it looked.

My roommate and I would frequently trade stories about body grossness. “You want to hear something gross?” she asked while transitioning into warrior pose in the living room. “Of course,” was always the answer. Typically, these sessions would be period-based, a new hair found on the chin, a bump or bruise appearing where (at least we thought) it didn’t exist before. We were fascinated by these bodies that simultaneously allowed us to hold a plank pose for a minute while also oozing, popping, and smelling. Every day of living in this body presented a new adventure. Has my period always been this way? Why do the clothes that fit yesterday feel like constraints today? Why do I find so much joy in peeling dead skin? It was also refreshing to find and talk with others who felt just as conflicted about their bodies as myself.

Author Mara Altman can’t explain everything, but her book Gross Anatomy seeks to resolve these tensions that exist about the body, our bodies. While much of the book is concerned with women’s bodies, I think the overall purpose of the text is to explore how we can live in these bodies, but understand so little about why and how they operate. And additionally, the anxiety we feel about our bodies. Anxiety over belly buttons, body odor, and buttholes, after all, are part of the human condition.

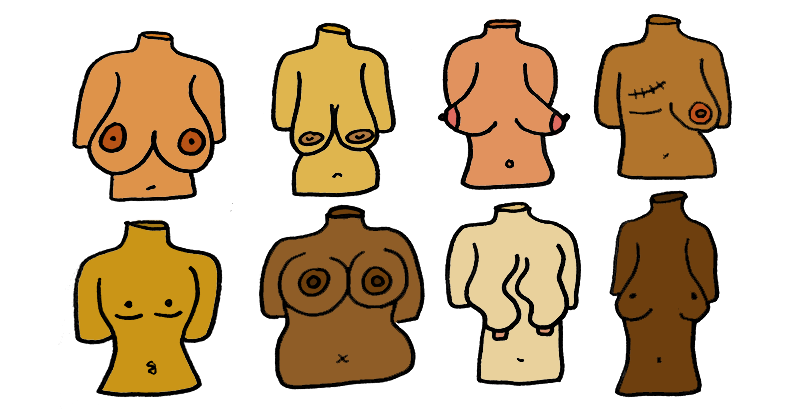

The book is dissected by “Top Half” and “Bottom Half,” with each chapter punctuated with absurd illustrations of the body, it’s functions, and tools to accentuate our anxieties about particular body business. Altman oscillates between curiosity, intellectualism, and humor. It’s this revolving perspective that opens up space for the reader to engage with topics that might be uncomfortable or weird: body hair, lice, boobs, orgasms, butts, and vaginal odors (just to name a handful). But Altman has so much fun exploring her own anxieties that it’s hard not to join the party and explore ours.

Each chapter is an exploration and a celebration of filth. In her chapter about boobs, she excitedly shares her story about going on her first naked bike ride to (protest? bring awareness) to double standards of toplessness. She is excited and distracted. There are a lot of boobs — ones that droop, others that remain perky despite the lack of support, a range of areolas. Despite how much time and money is spent agonizing over the perfect pair of breasts, Altman has fun recounting all the types she comes across on the ride, as well as putting her own into perspective. If everybody’s body is different, how can we hold ourselves to a standard of normal? In the immortal words of Mean Girls, the limit does not exist.

Read It

Gross Anatomy by Mara Altman

Altman articulates her experience and then explores. The refrain “I wanted to know” appears frequently, almost obnoxiously so. With this repetition, Altman relays the urgency of understanding. Why wait, when we have a wealth of information at our fingertips and can access experts in nearly everything (which is another standout about the book, there really is an expert on everything)? The pattern of articulation and exploration accomplished two things, primarily by building an empathetic bridge between reader and writer and secondly, by providing at least a partial answer to either the bodily issue or our response to it. There’s not really a need to explore how pubic hair happens, but there is a need to address why so many people are consumed by annihilating it from their bodies, why so many thought pieces are written about keeping it natural, and why I have to watch so many razor commercials using visual bush metaphors during a Real Housewives marathon. It’s a relief to know that others exist, who also spend time pondering these questions, and even more exciting that somebody has taken the “I wanted to know” to the next level and has done the hard work of finding and interviewing experts. And by experts, Altman doesn’t necessarily go to scientists, though much of her research leads back to academics. She does rely on the expertise of those working within the industries like celebrity bikini waxers, medical professionals, and Altman’s own parents and husband (who frequently acts as a sounding board).

I’ve wondered quite a bit about chin hairs. Way more than I did in my adolescence (when zits were taking up much more of my time), because they didn’t exist. My first chin hairs sprouted in my 20s, remarkably with a mole. If chin hairs are bad enough, the addition of moles, seemed a bit cruel. Now in my 30s, more chin hairs have sprouted. There is now a rotation of chins hairs that must be plucked. My friends and I have talked about our routines and our frustrations. Being, for example, away from your tweezers while stroking what feels like a Rapunzel-like chin hair. To read this struggle brings a new sense of encouragement and empowerment. It just feels good to know that somebody, a stranger, is working through what you’re working through. It’s ridiculous to be consumed about a hair not many, if anybody, will notice. But what Altman points out continually, is that the sense of panic women have over their bodies and all their grossness feeds into a larger cycle of socialization and comportment. There are plenty of sugar waxers, face threaders, and razors we can purchase to put us out of our anxiety (at least until it grows back).

Academic research and expertise are thrown in as a backbone to Altman’s experience within her own body. As she comes into her own body, we’re invited to consider and check in with ours. Walking to work, I told my friend (and former roommate mentioned above) all about lice and the science behind sex sounds. The science led us into conversations regarding our experiences and when and where we came to understand our own bodies. The academic underpinnings didn’t stifle the musing, providing the answers to all of our qualms, as much as it provided the license to muse further. Altman’s curiosity is infectious.

So often, it seems that to “honor” the body we must indulge in all these rhetorical strategies that make us overstate the body’s power and greatness. It is a temple. Altman frames this privileging as absurd. The body is an incredible entity. Its mechanisms and design full of complexities, but efficient. At the same time, it is chock full of the abject – of blood and puss, vomit and bile, snot and hair. We leave traces of our body everywhere. Instead of feeling continually disgusted or anxious, Altman encourages us to stop worrying and embrace our filthiness and “problem” areas. By embracing ourselves, she argues, we can devote our time and energy to other things and be richer both in mind and pockets.

But the point of the book is not to completely change ourselves either, as much as it is about raising consciousness for Altman to say “hey, me too.” There are many parts of herself that she doesn’t change even after talking with experts. She doesn’t discontinue shaving or start moaning during sex (she tries and fails) to amplify her orgasms. Instead, Altman offers a middle road. She offers a path of self-discovery, where people can step back and consider their own practices. She encourages the reader to want to know.

Shame can be good. Shame can remind us to be decent and kind to others. To feel shame or be shamed, forces us to reckon with ourselves. It’s the ultimate “shush” and nobody, regardless of how wrong they are, enjoys a “shush.” But as much as having a pointed moment can be a good reminder, we shouldn’t live in a constant state of shame. Gross Anatomy can’t do all of the work in helping us rethink and change our perception of the body, but it’s a heck of a springboard for diving into our own reasons for doing and thinking about the hows and whys of living in our own bodies. •

All images by Isabella Akhtarshenas.