While at the Small Press Expo in Bethesda, Md., earlier this month, I attended a panel entitled “Trans Memoir.” During the program, a small group of transgender cartoonists talked about how comics provided them with a mode of self-expression in which they could delineate their best, ideal selves and talk about issues and emotions — often difficult to articulate — that come with being trans.

Two recent books from the small press publisher Secret Acres — Flocks by L. Nichols and Little Stranger by Edie Fake — underscore what those cartoonists were saying. Both books examine the struggles of being transgender and dealing with dysphoria, albeit from very different perspectives and sense of aesthetics.

Flocks is a relatively straightforward memoir of Nichols’s life growing up in rural Louisiana, with one notable exception: While all the other characters are portrayed in a relatively realistic fashion, Nichols draws himself as a button-eyed rag doll. This has the effect of instantly engendering the reader’s sympathies — he looks so vulnerable — and also visually signifying that the protagonist feels like an outsider.

Assigned female at birth, Nichols grew up in a deeply religious and conservative community and thus was constantly plagued by feelings of shame and confusion about his sexuality and gender. These feelings of anxiety and self-loathing are frequently depicted by arrows or lightning bolts labeled words like “queer” or ”pressure” that point both inward and outward (but usually inward).

Much of the book is concerned with Nichols’s journey towards self-acceptance and self-care as he grows to maturity and eventually transitions to male. But what’s interesting about Flocks is that Nichols refuses to provide any one-sided condemnation of either his family or religious community. While he makes starkly clear the anguish and fear he felt at being “different”, he also praises his parents for giving him the confidence to excel at school and eventually attend M.I.T. And he also refuses to spurn religion, instead, finding a church that espouses a spirituality sans condemnation.

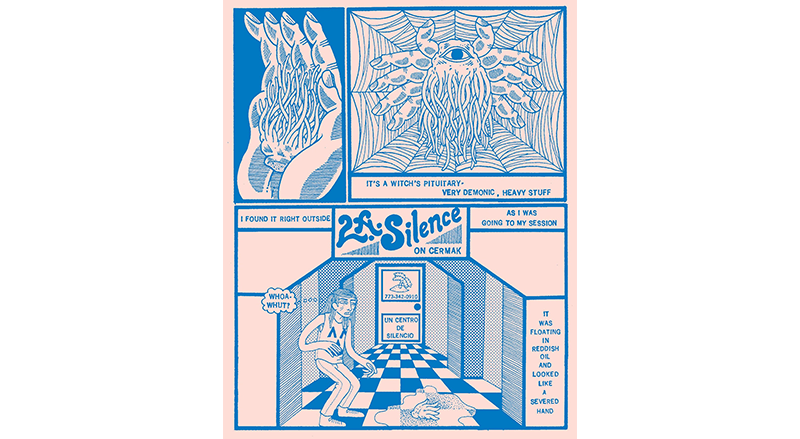

Edie Fake, meanwhile, takes a more surreal and at times, a horrific route to articulate his concerns over gender and sexuality. The short stories and drawings that make up Little Stranger often take contorted paths, but the emotions underlying them are very real and raw.

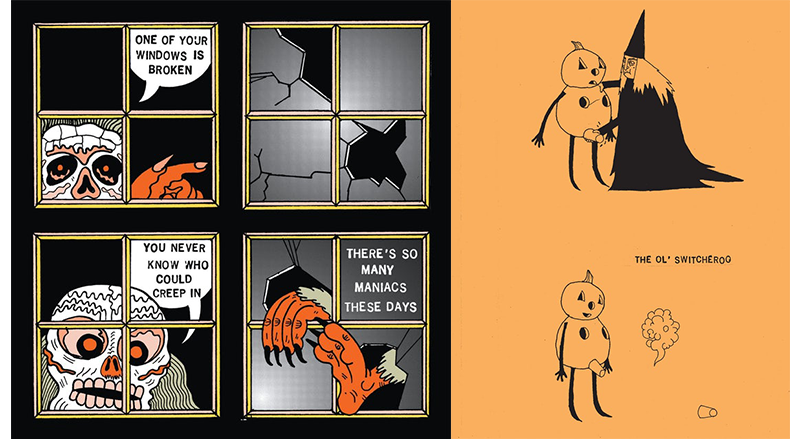

Not one for subtlety, Fake’s comics are filled with makeshift genitalia and other body parts that transmogrify with alarming rapidity. A cow’s udders become spurting phalluses, a group of leeches become sex toys. In “Foie Gras,” images of preparing a turkey or cutting a fish become strangely sexual when juxtaposed with text that reads “fuck me like this”. In one cartoonish sequence, a witch removes two cup-shaped breasts from a pumpkin-headed creature, placing one at the crotch instead. “The old switcheroo” the witch exclaims as she disappears in a puff of smoke.

Many of these sequences are funny despite (or perhaps because of) their explicit nature. But there is also an air of menace throughout Fake’s work. In “Night Taps,” a demon appears at a window and cryptically warns that “your house is like a cracked egg . . . what could ever protect your fragile shell?” A hand holds a card that reads “This card has been chemically treated. In 3 days your prick will fall off.” In “L.A. Silence” Fake visits a clinic where he suddenly grows breasts and almost drowns in a sea of milk.

Fake’s work can often be cryptic and disturbing, but his attempts to articulate his anxiety, desire and even happiness about being transgender rings through loud and clear and is not so far afield from the message of acceptance and love that Nichols emphasizes in Flocks. In both these books, people in the LGBTQIA community and beyond can find empathy, recognition, and solace. •

All images courtesy of the author.