In his fictional account of Sir John Franklin’s Arctic exploits, the German novelist Sten Nadolny saddles his hero with a condition that explains his successes and subsequent death in the ice. Franklin’s staid, systematic approach, instead of being a handicap, in The Discovery of Slowness, sets him apart from the Industrial Revolution’s hurried masses and perfectly qualifies him for expedition planning. While that twist serves as literary conceit and civilization critique, it points to a vital truth: a deliberate pace can be beneficial where new worlds beckon and adversity rushes in.

Slowness in 15th to early 20th-century exploration was not necessarily a matter of personal disposition or choice. Walking, sailing, and riding were the main forms of locomotion before the advent of steam or combustion engines. Cumbersome gear and logistics combined with sickness, seasonal vagaries, and diplomatic negotiations delayed many explorers. Francis Drake’s circumnavigation of the globe took three years and his compatriot Darwin’s on Beagle almost five. Wintering on ships frozen fast in pack ice, captains struggled to keep crews busy with impromptu entertainments and domestic routines. For feverish, tent-bound convalescents in the tropics as well sketching and journaling were productive means to bridge enforced layovers while maintaining sanity in the long-term sojourner.

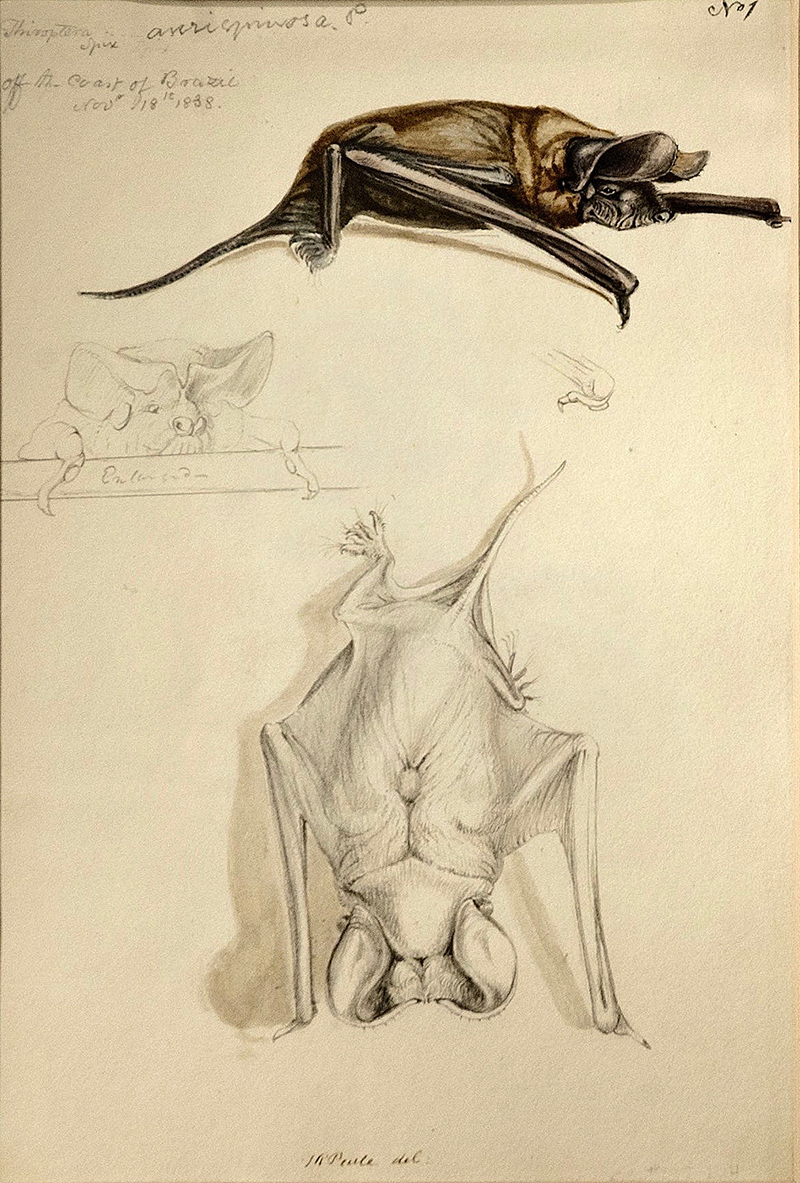

Data gathering, of course, was the foremost purpose of inquisitive travelers’ notebooks. The informative context alongside the artifacts or natural objects expanded humankind’s trove of knowledge by providing material for further study upon the diarists’ return.

The heydays of Europe’s exploring overlapped with the invention of photography, not by coincidence. Politically ambitious nation states prospered through scientific curiosity that furthered technology, which in turn advanced science. While the camera was a new tool for documenting reality, its use in exploring remained limited. Early, 19th-century daguerreotype cameras weighed a whopping 110 pounds and before tripods, had to be put on portable tables. Tintypes were too heavy and bulky to transport without a packhorse or an oxcart. Glass plates broke easily. A wall tent could do double duty as a darkroom in the field, but curing solutions and paper had to be stocked if pictures were to be developed there. Lastly, photographic equipment was expensive.

Color veracity posed problems also. Invented in 1861, color photographs blunted the natural spectrum. Daguerreotypes hand-tinted by miniaturists had become popular in the 1850s but, arbitrary and costly, could not match a landscape’s palette either. The first practical, commercially successful design — the autochrome — arrived only in 1907. For these reasons, the thousands-of-years-old practice of illuminating manuscripts and commenting in their margins still flourished in the Age of Discovery. Adela Breton’s nuanced copies of Yucatán Mayan frescoes, painted before the days of color photography, are the only polychrome record of works whose vibrancy quickly dimmed or eroded once they were exposed to the elements.

Honoring that tradition, Explorers’ Sketchbooks, if titled prosaically, takes readers on a sublime 70-chapters trip around the world and through time. The showcased samples — drawings and facsimiles of journal pages — range from the era of caravels to that of space ships. Nutshell biographies accompany each entry, and the book’s pictorial smorgasbord and alphabetical organization invite nibbling rather than cover-to-cover consumption. Each morsel should be savored. Interludes by modern-day author-explorers like Wade Davis or Huw Lewis-Jones add contemplative angles and relevance. “The work you do is just a lens through which to view and experience the world,” muses Davis, an ethnobotanist and National Geographic Society Explorer in Residence who has probed Amazonia. His credo rings true for artists and scientists both.

Explorers’ Sketchbooks features celebrities such as Amundsen, Speke, or Shackleton while introducing enough faces fresh even for readers well versed in the history of exploration. Wayfaring Caucasians dominate this roster, as they long did the planet. In part, this results from the dearth of non-Western reports available to the book’s Anglophone editors. Chinese sailors had invented the compass by AD 1111, and Arabs navigated by stars before Marco Polo embarked for Shangdu. Siberian hunters crossed into the New World anonymously via Beringia at least 13 millennia before one Cristoforo Colombo. And two million years before that, bands of Homo erectus had walked out of Africa. In short, while discoverers crowed their accomplishments, the discovered largely stayed voiceless.

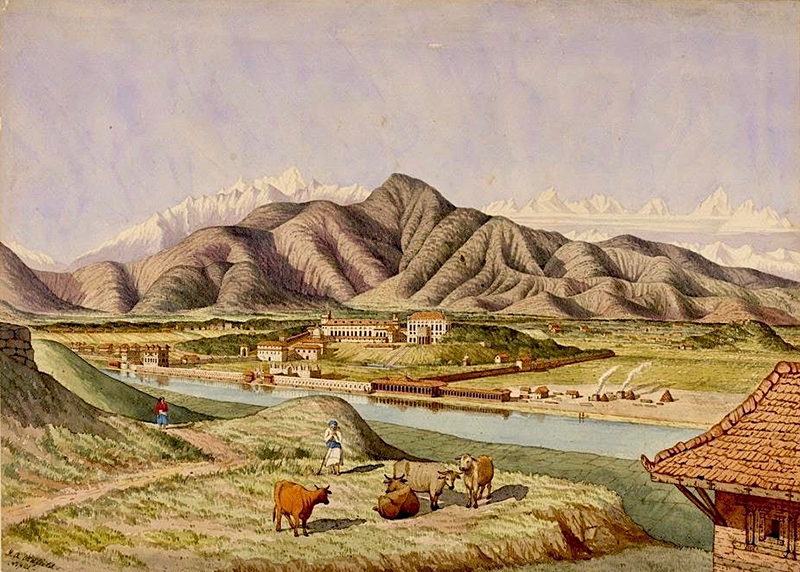

Women voyagers, still less famous today than the men, likewise are outnumbered, a reflection of patriarchy, just as the lack of black dog sledders was of racism, colonialism, and unequally distributed wealth. Luckily, nine chapters of Explorers’ Sketchbooks brim with female finesse and wild feats. Kudos to the editors for including Margaret Mee who bedded down with jaguars, her namesake Margaret Fountaine, who jumped off a derailing train once, and Gertrude Bell, an army intelligence colleague of Lawrence of Arabia who spoke eight languages, set out on horseback provisioned with carpets, china, and silverware, and whose fearless dignity impressed short-fused Bedouins.

Not just the breadth but also the depth of this splendidly curated potpourri of personalities and techniques is remarkable. Flashes of cartoonish humor, distress, homesickness, and doubt show scientists letting their hair down — very unlike the self-image they presented, if they did at all, in monographs or official reports. “I have never known any man to be placed in such a diametrically opposite position to the goal of his desires,” Amundsen scribbled at the South Pole. Hearing of Cook and Peary’s alleged reaching of the North Pole, Amundsen’s locus of longing since childhood, he’d spontaneously rerouted his sloop Gjøa, heading south instead. Like Claude Lévi-Strauss’s opening to Tristes Tropiques “I hate traveling and explorers” such glimpses easily undermine narratives of single-minded, heroic (con)quests. Taken at face value, John Auldjo’s scene of alpinists glissading with walking-staff rudders toward a crevasse allows but one response: What were they thinking? Yet it can also be read as painterly self-aggrandizement, as a proof of having lived dangerously that lured city dwellers with dreams and money to spend.

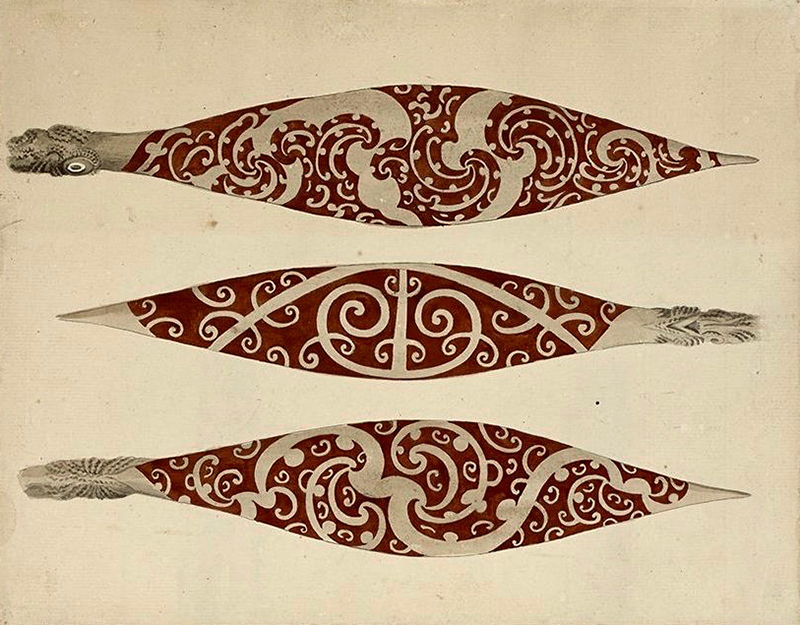

The notebooks’ intimacy, diverse handwritings, and reportage-style illustrations telescope distance and time, making these women and men familiar, kin to the curious reader. Plants, animals, and indigenous people leap from the page in a vividness that raises them above the status of mere specimens. Human individuals, often befriended, likewise were remembered: Kipahalgwa’, Bengulu, Tatanka-Kta, Abdul Samud . . .

Read It

Explorers’ Sketchbooks by Kari Herbert and Huw Lewis-Jones

Howard Carter’s watercolor of Horus on the wall of Queen Hatshepsut’s mortuary temple resurrects the falcon-winged god in all its emerald glory, complete with the mural’s flaked paint and gaps between stone blocks. William Beebe’s nightmarish deep-sea fishes hauled up in nets and painted by Else Bostelman could have been creatures from Mars. When they were displayed, the public at first mistook them for figments of the imagination. The book’s illustrations question viewing habits, sensibilities shaped by textbooks, video clips, Google Earth, and glossy nature photography; they spur dragons of fancy not just through the maps’ empty spaces. Some, in their roughness, stress event over exhibit, subjectivity over accuracy, and process over a polished end product. A bushman plays his goráh, the tune transcribed underneath without the help of recording devices. Paired on another page, with a packrat’s aesthetic, the Karachi toad and a pearl-studded nose ring equally matter. This book, itself an exploration (of obscure archives and private collections), is no print cabinet of curiosities, no hipster antiquarianism or large-format box of madeleines. Instead, to quote Robert Mcfarlane’s fine foreword, Explorers’ Sketchbooks preserves “textures of feeling and imagination.”

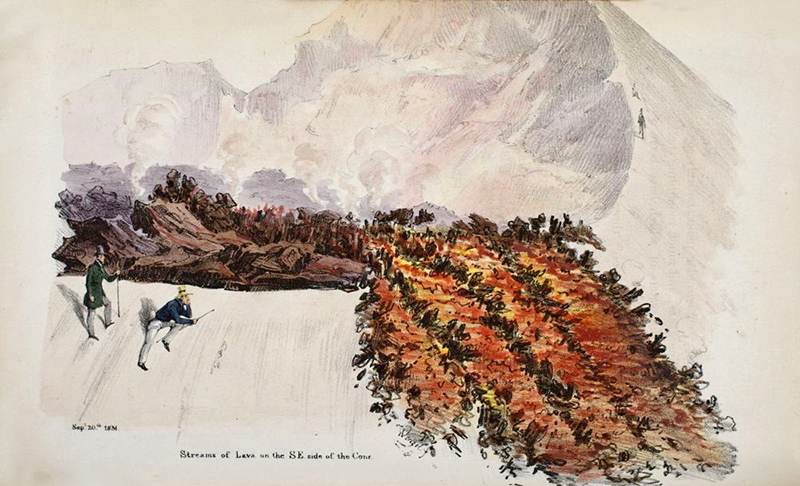

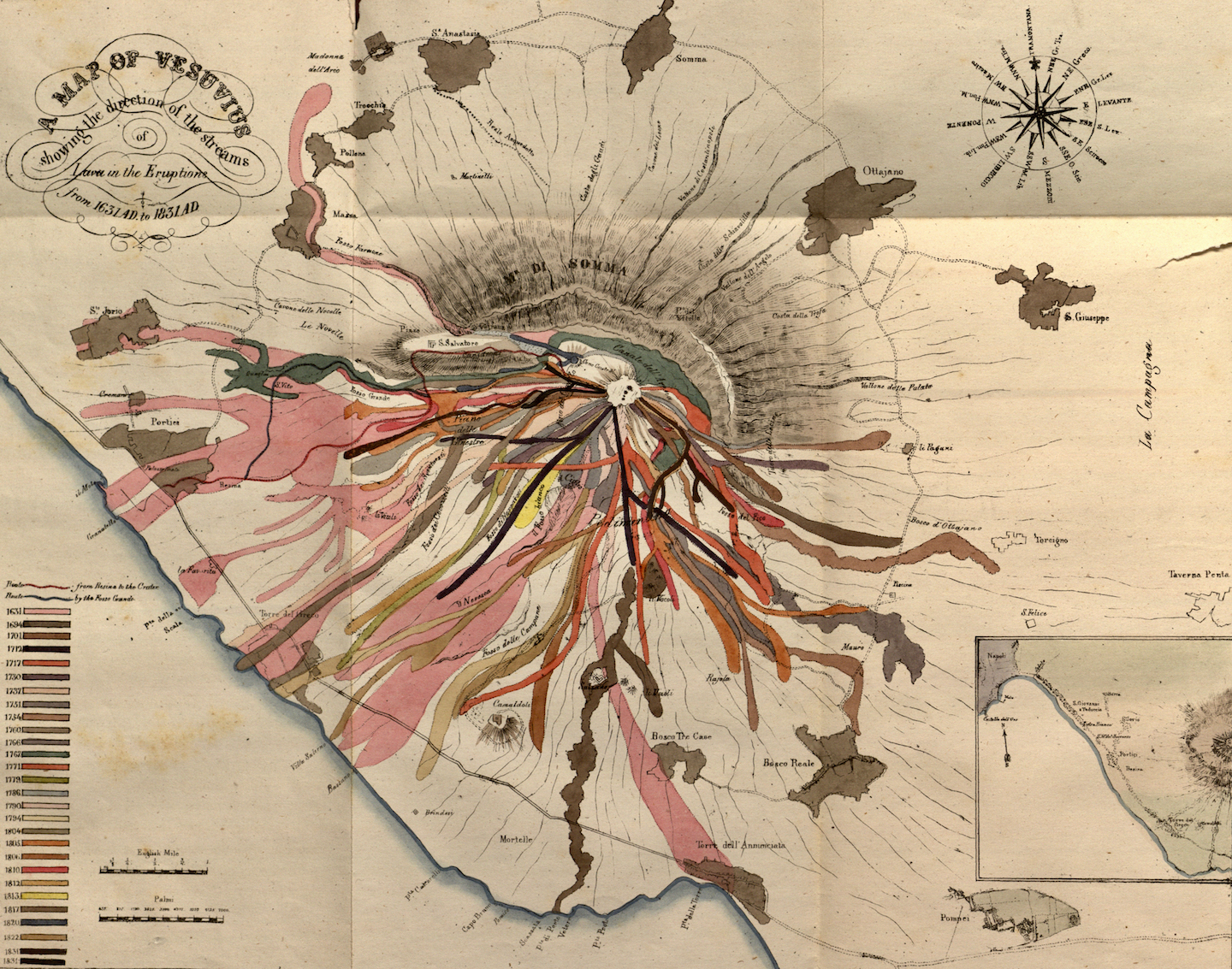

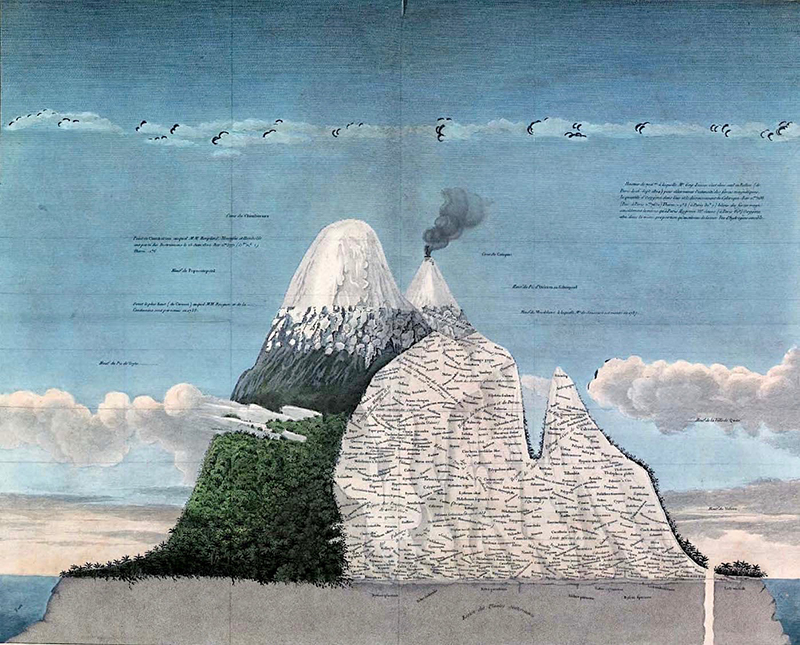

The many hand-drawn maps, with ornate compass roses, aquarelle shadings, and stylish calligraphy — regardless of errors or distortions — tower above their software-generated, mass-produced counterparts as far as artistic merits go. Several anticipate composite or time-lapse photography. In his bird’s eye view of Vesuvius, the mountaineering cartographer John Auldjo color-coded successive lava flows in a way that suggests tentacles on a jellyfish or ribbons streaming from a maypole.

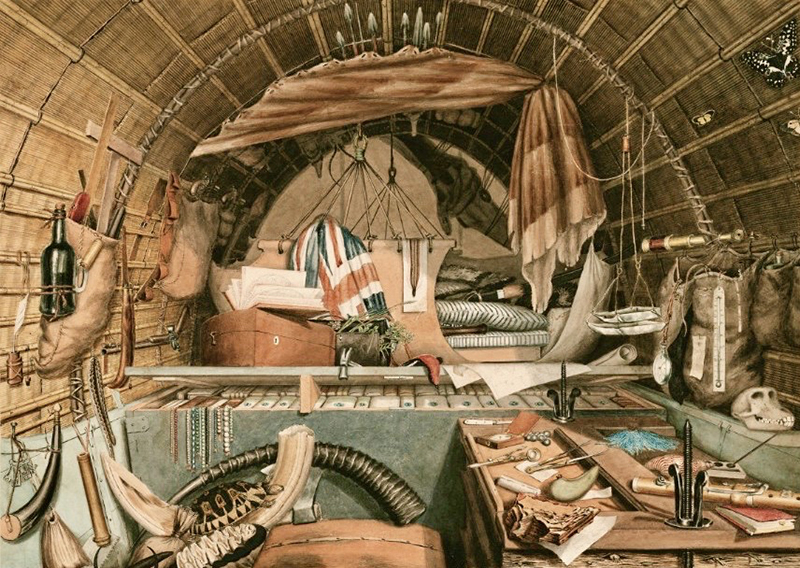

With exposures of minutes or days rather than photography’s seconds, these slices of lives in foreign lands delve deeper into a world so much more beautiful than it needs to be — it took William Burchell 120 hours spread out over a month to sketch and paint a still life of his collecting wagon in South Africa’s Cape Province. Observers in the thick of things honed their observation skills. The more they looked the more they saw and committed to paper or memory. “The vitality of a landscape or journey is in its detail,” the globetrotting Colin Thubron writes. With their noses in guidebooks, tourists touch the skin of a place; travelers want its meat and bones, the mundane miracles not listed in Fodor’s. This brand of attentiveness seems even more important in an age when penguin colonies can be spotted with satellite imagery. (Their krill diet leaves pink excrement stains on the snow.) Compared to drawing or painting, snapping pictures leaves the brain unchallenged. Just as we no longer recall phone numbers because we store them on phones, vision digitized atrophies.

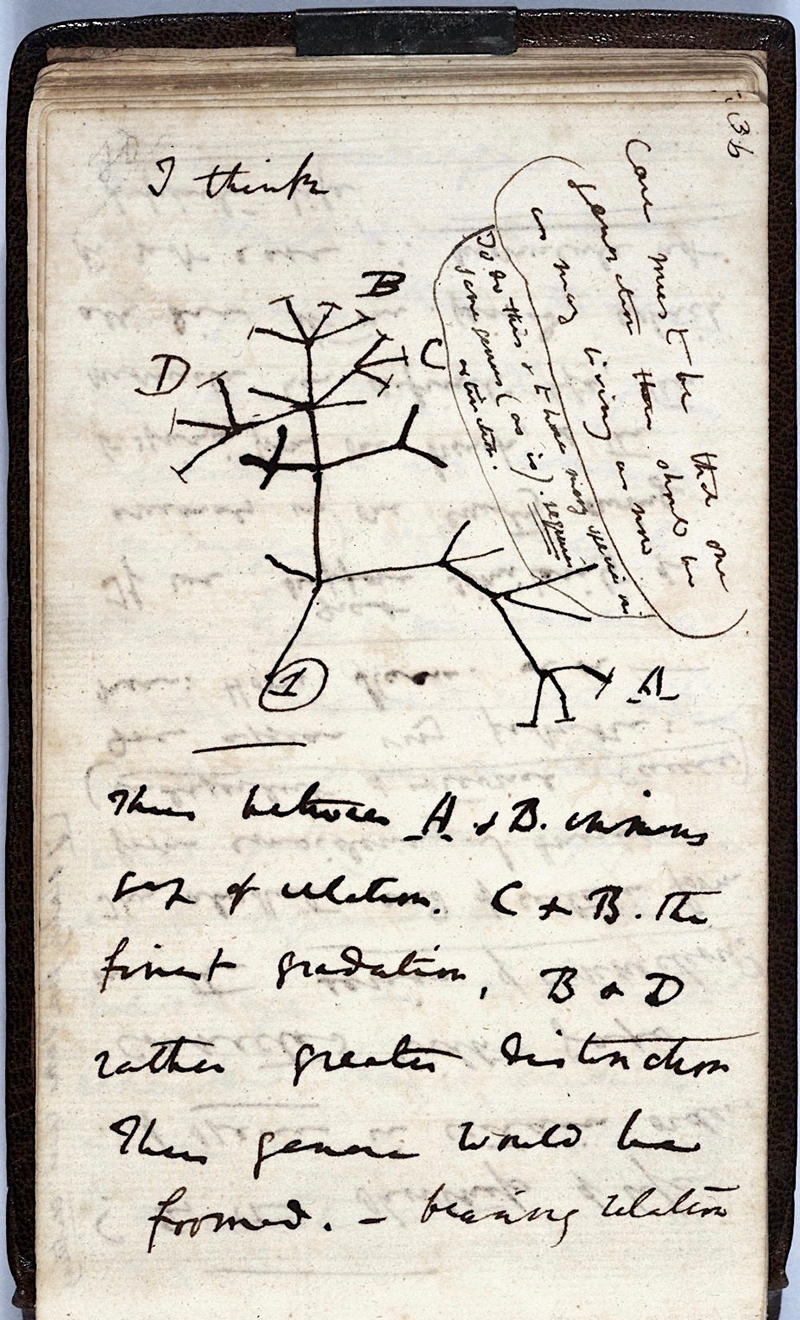

Unlike photos, visual diaries enabled adventurers to think on paper, to conceive ideas and develop schemata that later could be disproved or fine-tuned. Darwin, who admitted being a very slow thinker, first conceived the evolutionary relatedness of species as a corral-like “tree of life” doodled in his 1837 notebook months after his grand tour, that “hurricane of delight & astonishment.” Organizing his notes aboard Beagle on the way home, he’d started questioning the immutability of species.

A few annotated sketches contain question marks of uncertainty or follow-up queries. Attention sharpens perception, especially with regards to patterns the neutral camera lens cannot detect. A good example is Alexander von Humboldt’s altitudinal map of vegetation zones on Ecuador’s Chimborazo volcano. Its holistic perspective, later refined into the concept of “life zones,” is a graphic reminder of Humboldt’s standing as the father of ecological thought.

“A skillful painter is also to be carried . . . to bring the descriptions of all beasts, birds, fishes, townes, etc.,” John White advised financial backers after his stint on Virginia’s shores. An expedition’s leader often was not its designated artist — other chores and responsibilities weighed too heavily. Occasionally, expedition artists, though rarely famous then or now, already had tested their mettle and were enlisted for that very reason. The landscape painter Frederick Dellenbaugh who in 1899 steamed from Seattle to Siberia with John Muir (and another writer, the eminent John Burroughs) had been among the first people to row the entire Grand Canyon, as a member of John Wesley Powell’s 1871 expedition. Not all chroniclers always strove to capture details photo-realistically, and few rivaled in talent John James Audubon or Adela Breton, to begin with. Sometimes they were in a hurry, or their fingers became “all thumbs” from the cold. The wet paint attracted hordes of flies. Elsewhere, it froze as soon as the painter put it on paper. “Twice before I got that rough sketch,” Charles Turnbull Harrisson wrote in the Antarctic, “I had to run around to get some warmth.”

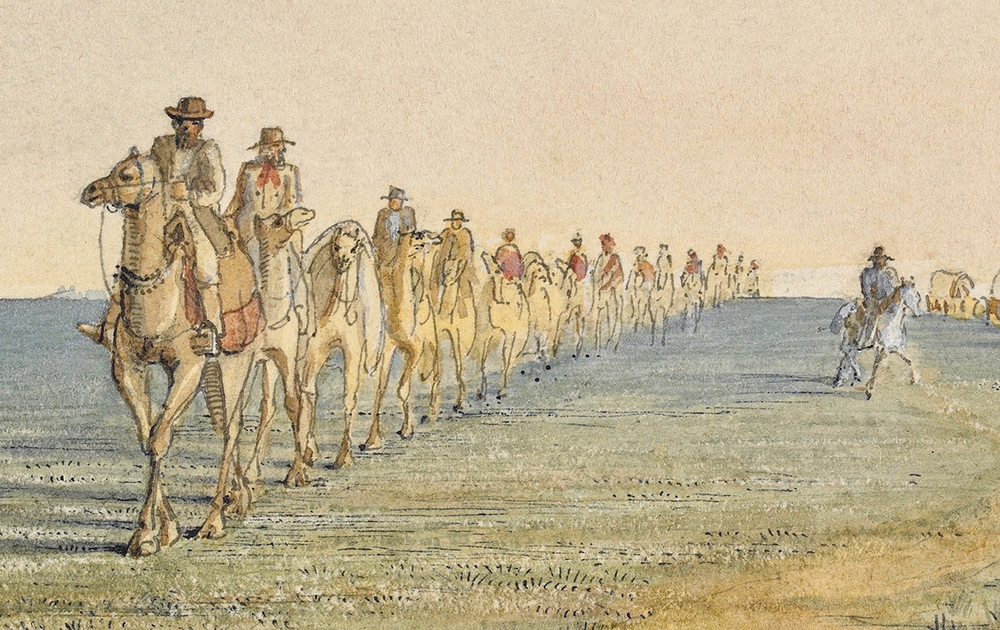

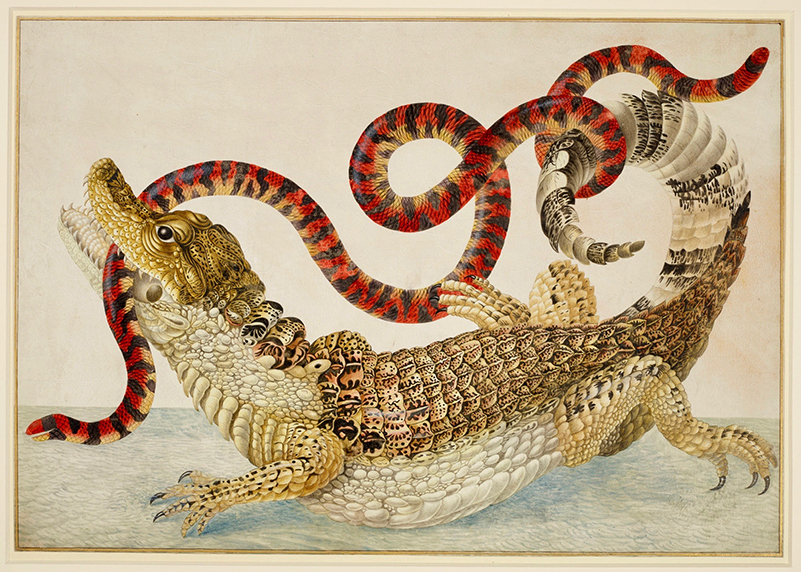

Despite not normally traveling light, weight and volume were a concern, and crucial items could be missing. “Having no books with me, in reference to birds, I do not know its [the Curali’s] scientific name,” Ludwig Becker wrote during Burke and Wills’ 1860 coast-to-coast transect of Australia. Yet his watercolor of the caravan shows pack camels and a train of horse-drawn wagons. William Burchell, supplementing his kit, carted trade goods, a brandy barrel, sextant, and telescope, and 50 natural history tomes in his custom-designed, mobile home. Everything Carl Linnaeus needed for five months of botanizing in Lapland fit into a leather bag slung over his shoulder. Being an adaptable and inventive species, explorers overcame material shortages. When David Livingston witnessed slave-traders massacring Congolese villagers, he found himself out of paper or ink to record the atrocity. After tearing pages from a copy of the London Evening Standard he crushed berries, using their juice as ink. His words over time faded to near-invisibility and only recently have been recovered with spectral imaging technology. Others, like the 17th-century German naturalist Maria Sibylla Merian, meticulously planned their art supplies. Awed by exotic insects in the Wunderkammern of Dutch natural history collectors in 1699, the printmaker’s daughter and her own daughter, Dorothea, sailed to South America. She carried skins of unborn lambs from Amsterdam to Surinam, delicate canvases for her brilliant vignettes.

Robert Flaherty, the director of the classic film Nanook of the North and like its protagonist an old Arctic hand himself, aptly summed up the relation between creativity and discovery: “All art is, I suppose, a kind of exploring.” Conversely, all exploration, at least the rewarding kind, is journeying elevated to an art form.

Handsomely designed and produced, Explorers’ Sketchbooks will appeal to artists, armchair travelers, bibliophiles, and history buffs. No compendium better conveys arctic cold and desert heat, the sounds, scents, and sights, grit and grandeur, or the frustrations, excitements, and breakthroughs of what can be considered humanity’s greatest and oldest endeavor. •

Images provided by the author. Feature image is a detail from Ludwig Becker’s Crossing the Terrick-Terrick Plains, 1860.