I just came from a performance of Giselle, the classic ballet in which the heroine, a peasant girl, falls in love with a prince and then dies when she discovers that he is betrothed to a noblewoman. I love this ballet and watched it with rapt attention, but I was struck, in the context of our #MeToo moment, of its problematic appeal and that of other ballets that I love like Sleeping Beauty, Romeo and Juliet, and Swan Lake.

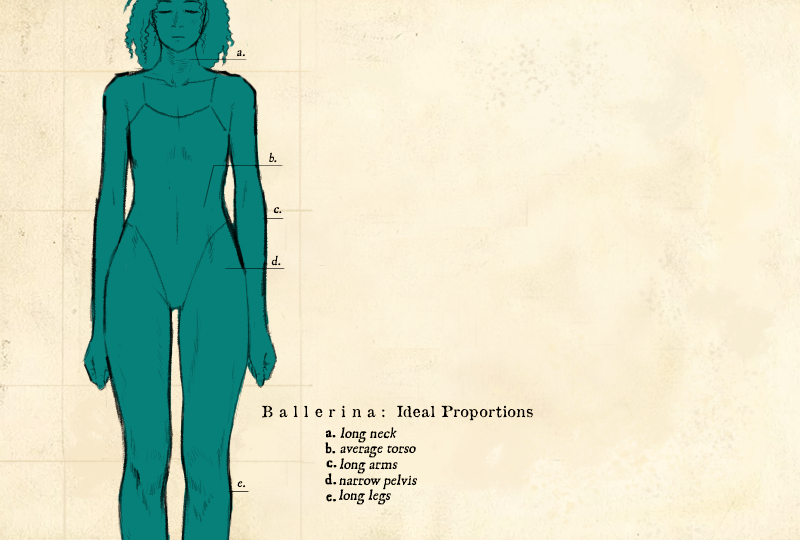

Not for the first time, but more strongly, I was brought up short by the contradictions inherent in what I was seeing. One cannot separate a classical ballet of this kind from its reliance on extreme, stereotypical gender representation. The tutu is a frilly exaggeration of a woman’s hips and the longer skirt is its more romanticized extension, not to mention the diaphanous nightgowns that figure in sleep-walking scenes and bedroom encounters. The male dancer is the support, the prop and pander, to this gauzy female caricature. Often the ballerina dies — in Kenneth MacMillan’s Romeo and Juliet there is a duet, if it can be called that, with Juliet’s lifeless body. Ballet also demands rigorous physical conformity from the female dancer. She must be of a certain height and weight, must have a certain leg length, and must possess good turn-out and feet. (My teacher informed me that I had none of these at age 12.) The male dancer, by contrast, is mostly defined by his bulging codpiece and delineated buttocks. So long as male dancers can jump and support their partners, they can be more variable in their physique.

But what strikes me the most as dramatically regressive, while also being the locus of my fascination, are the pointe shoes that ballerinas wear. (Male dancers don’t wear them, except in the most unconventional circumstances.) I have always been besotted by them. Despite having been told early on that I had no future as a ballerina, I somehow managed to acquire a pair and take a few lessons in them in my late teens. Just looking at those pink satin contraptions, or if you will, cages, for the feet still gives me a jolt of pleasure.

We excoriate the ancient practice of Chinese foot-binding, but the toe shoe binds the female dancer’s foot and in a particular way that involves more than the reduction of movement. There is that — the incremental forward movement on the toes that, if prolonged for any length of time, always elicits ecstatic applause from the audience. But there is the added image, central to ballet, of the female dancer posed on her toes with the support of the male consort who is then turned, fast or slow, in pirouette — a perfect doll-like figure displayed dramatically for the male gaze (To appropriate the phrase used most commonly in critique of classic narrative film). But what would I have given as a girl to be spun that way, like a gauzy top.

The appearance of sylph-like weightlessness that the toe shoe, combined with the diaphanous ballet skirt, projects is contrasted by what the shoe does to the feet. They are invariably bloodied and gnarled, with unsightly smashed toenails. The feet, along with the emaciated ballet body, as eating disorders in the ballet community are all too common, reflect the trade-off behind the ethereal image of the ballerina.

And yet for me, even knowing how crippling the shoes are, they seem to be the very distillation of a certain kind of beauty. I love the pink satin shank. (Girlie pink is the presiding color for the ballerina: her shoes, her exercise tights, and her leg warmers, as well as her tutus, are generally pink.) I love the ribbons floating from the sides, stitched by the ballerina’s own hand, and the hard toe box that gets dabbed in resin before practice or performance. I think of that hard toe as the complement to the satin shank, the place that announces that hardness and wear underlie the delicate, sleek exterior. Indeed, the very idea that these slippers must be continually replaced, that the work of dancing wears them out almost as soon as they are acquired (sometimes mid-performance), despite costing above $100 a pair, gives them an additional mystique. They, like the feet of those who wear them, must endure pounding abuse but give the impression of an unblemished delicacy.

Having just seen Giselle, one of the ballets with extended pointe work in the second act, I also considered the optics of the ballerina dancing on her toes. What is so alluring is not only the constraint of the feet into a satin projectile but also, of course, the elevation of the foot — making it longer than it naturally is (fashion illustrators grasp this point in their sketches; their female figures are always 9 or 10 rather than the realistic 7 heads in length). Moreover, ballet continually emphasizes the difference between the flat and elevated foot. The flat foot is mundane, awkward, even clownish. (Charlie Chaplin had that kind of flat turn-out in his films, though he wore oversized shoes rather than pink slippers.) One can identify a ballerina on the street by that duck walk. But on stage, the flat foot is used to contrast the elevated one, underlining the moment when the ballerina rises to her toes and becomes magical. This contrast between the flat-footed everyday and the elevated etherial is built into the aesthetics of classical dance.

I am not alone in my fascination for the toe shoe. You will find a slew of sites on the internet exploring their construction and use. Dancers, interestingly, only began to dance on pointe in the late 19th century. For a short period in the 18th century, they were elevated by wires called flying machines. The first ballerina to dance on her toes was the Italian ballerina, Marie Taglioni, whose shoes were perfected in the early 20th by the great Anna Pavlova, who pioneered the boxed toe. (Her feet were highly arched and needed additional support.)

Dancers develop rituals around their toe shoes. They can spend an hour or more getting their shoes ready before a performance: sewing on the ribbons, breaking in the shank by knocking or even hammering, sometimes coating the satin with shellac to make them sturdier, and inserting padding of various kinds. Breaking in is important because the shoes, despite their hard toe, should not make too much noise on the stage — loud landings are decried as contrary to the ballerina aesthetic.

New materials for shoes crop up now and then, but satin, cardboard, and glue, with leather for the sole, remain the norm as dancers tend to gravitate toward what was used historically. Indeed, the reverence for the toe shoes of great dancers is legendary. One story has it that a group of fanatical acolytes, known formally as balletomanes, gathered and ate the shoes of Marie Taglioni. (Though her shoes did not have the hard box at the front that would have made digestion difficult.) A worn pointe shoe that once belonged to Anna Pavlova is now selling on the internet for $25,000. Only recently have ballet shoes, generally pink though sometimes white or red, been manufactured in brown to complement the skin tones of people of color. Occasionally, male dancers are given roles on pointe, but this is unusual.

Ballet, like so much else in our current society, is infused with sexist elements that are also elements of beauty. To tease these apart is impossible and should give us pause to contemplate the mixed nature of art and how hard it is to condemn past inequity and abuse when its codification persists in so much of our cultural expression. If one is a social justice purist, one would never go to a ballet or allow one’s child, male or female, to take ballet lessons. Ironically, the only instance where I’ve felt the spectacle surmounted gender convention was when I saw a 1977 tape of Nureyev in Romeo and Juliet. His exceptional stylishness and the height and drama of his jumps were such a riveting complement to the delicate, if older, British ballerina, Margot Fonteyn, that the very extremes of their performance seemed to explode convention making it both compelling and ironic, especially when their stage pairing was placed alongside their ambiguous relationship to each other in real life.

I suppose a more conventional revision of the objectification of the woman in ballet is Matthew Bourne’s all-male Swan Lake, first performed in 1995 and recently revived. Yet I am unsure of whether this is actually revising the stereotypes of classical ballet or merely effecting a transfer of the male stereotype into another register. In one review, the corps of the Bourne Swan Lake was described as “thuggish.” Be that as it may, it’s unlikely that Bourne’s innovation will entice yearly pilgrimages by crinolined little girls and their mothers. No amount of #MeToo will supplant the popularity of The Nutcracker every December, a ballet that enforces all the conventional gender stereotypes, not to mention providing a hint of pedophilia in the creepy Drosselmeyer at the young girl’s bedside and, monstrously, seated atop the grandfather clock.

It is no wonder that sexual scandal has engulfed the ballet world. Everything about it is designed to represent the female dancer as conventional prey and complement to male muscle. George Balanchine, the great choreographer and teacher, was a notorious predator, grooming his prima ballerinas for his repertoire and for his bed. Peter Martins, who succeeded him at New York City Ballet, can hardly be expected to have been different — he learned at the feet of the master.

It’s interesting to think, however, that classical ballet is a kind of paradox with respect to female empowerment. On the one hand, it supports an exaggeratedly feminine image — frilly, frail, ethereal, doomed. On the other, it places this figure center stage and puts the entire burden of the production on her small shoulders or, more correctly, on her mangled feet.

I should add in closing that the toe shoe and the high heel are partners in paradox, versions of each other. High heels are the workaday version of the elevated leg that ballet turns into a performance spectacle of the highest order. Thinking in these terms can make ballet seem even more regressive, or it can make those impossibly high heels that some of us wear (or would like to wear) seem more artful and expressive than we would normally think of them. Take your pick, so long as you don’t break your neck. •

Images illustrated by Barbara Chernyavsky.