As the years pass I find myself wondering more and more if what I remember about my childhood are the events themselves or merely a memory of those events. There is a half-awake feel about these memories, a sense of being twice-removed, as if somewhere along the way the direct chain of cause and effect had broken, replaced by a more vaporous connection. Still, I am aware of something deeper that is just beyond my grasp. Events don’t seem only distant in time, they seem more like scenes from a movie that keep flashing through my mind that I struggle to place because I’m no longer sure I’ve even seen the film. Yet I am aware of myself as a player in those scenes. The more I try to wring meaning from these memories the more I realize that the way to do it is to unveil the universals that lie beneath them. Only then will they reveal themselves as more than a collection of unrelated episodes grown hoary with time.

I was born in the Point Breeze section of Philadelphia in a two-story brick rowhouse. It was the first house my parents bought after they were married and where my father was about to begin his medical career. From Colonial times through to the early twentieth century homes in Philadelphia were commonly built of brick, and Point Breeze was a classic example of the type. Standing on the sidewalk in that first neighborhood in the first years of my life, whichever direction I looked revealed long rows of red brick homes, usually two stories high, some with three and, less frequently, four. Grass, except in tiny back yards that butted against even tinier alleyways, was almost nonexistent in those canyons of brick. On cloudy days the neighborhood seemed to huddle beneath a grayish shroud; on cold rainy days it seemed to draw inward on itself and was downright depressing. Despite the dearth of greenery those block-long brick walls formed by the rows of identical houses were boundaries of my youth. I felt a strong sense of place and time and that it was right for me to be there. By the time I was ready to begin grade school my parents had moved a few blocks west to the Stephen Girard Estate, originally the home of the wealthy Colonial-era philanthropist and banker. It was there that I spent the next 12 years of my life.

Over 50 years have passed since my youth in South Philly. In all the times I have gone back I have never returned without the sensation of putting on an old comfortable piece of clothing, a shirt, maybe, where the sleeves are just the right length and the shape and size of the shirt conform perfectly to my body. No matter how long I’ve been away coming back always seems the most natural thing to do. I become aware all over again that, even though I no longer live there, South Philly continues to live in me. My youth is traced in the crisscrossing of a hundred side streets, in the paved pathways through Stephen Girard Park near my house, in the building — and store — fronts that have worn the same faces for decades. It is a story written in brick and stone, asphalt and grass.

Just as time announces itself to me in the lines that appear in my face so the old neighborhood announces the passing years through disappearance: the Broadway movie theater that was my Saturday afternoon haunt now a drug store chain; the Robert Hall clothing store where my parents bought my brothers and me new clothes each Easter now a bank; the G.C. Murphy’s on Oregon Avenue now an emporium where everything sells for a dollar. But these are only small differences. And yet, so much is gone forever:

. . .the old Italian women scrubbing the three marble steps outside

the front door of the houses until they sparkled. . . the horse-drawn

white Abbott’s milk truck with the big red A on its side panels. . .

the bright red Philadelphia police cars. . .

But even the lack of these familiar sights isn’t enough to destroy the sense of permanence and belonging that rises up around me as I walk the streets. It was well into the 21st century after more than 40 years at the same location that Kerrigan’s Typewriter Store stopped displaying typewriters in the window. Did Mr. Kerrigan own the building and not have to worry about actually selling typewriters to pay a mortgage? If he didn’t own it how did he possibly make a living selling typewriters in an era of personal computers? The store is gone now, replaced by a private home.

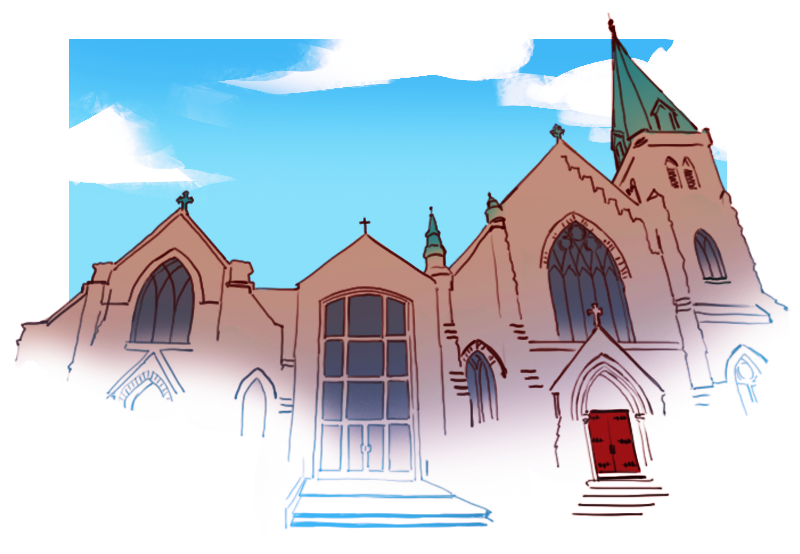

A block farther east from Kerrigan’s was the Trinity Lutheran church, a solid medieval-looking building of gray fieldstone that had stood on that corner for over one hundred years. One day a large sign appeared announcing the coming construction of 12 luxury townhomes on the site. Two years passed with no evidence of construction or demolition. The church just sat there in grim defiance of its planned demise, an indestructible monument to its own longevity. Ultimately, the wheels of progress creaked into motion and another piece of my history gave way to the wrecker’s ball. Now modern townhomes sit where children eat and sleep and laugh and do their homework and adults worry about bills and argue and make love where others once worshipped. Does the fact that this was once holy ground exert a secret influence that shapes the lives of the homeowners without them knowing it? I wonder. The church itself was for me always a symbol of “the other.” What did Lutherans believe and what rites took place behind those gaudy red doors that stood in such stark contrast to the more respectable brown ones of St. Monica Church a few blocks east? In eight years of walking past the church each day on my way to and from school I don’t remember ever seeing anyone go in or out of the building, either on a weekday or a Sunday. To this day I wonder what lurked in the silence on the other side of those doors that have now either been splintered into a million fragments and scattered to the winds or lean quietly intact against the walls of some warehouse, waiting. . . waiting. . . for what?

I turn off Porter Street, head down 19th, then back toward the public library at 20th and Shunk. It now wears a different front door and a new iron railing that weren’t there when I was growing up a half a block away. Now that I see the railing I recognize it as the one thing that had been missing all those years. Libraries are moments of stillness in the movement of life, and they should be marked as such. The railing is a visible sign that the library is a place apart, a place for learning, for study, a place to converse with famous people from history, read about distant times, walk in different places.

Not much has changed on the outside of the library but, inside, I see that a great deal has changed. Although the ornate coffered ceiling remains, gone is the soft yellow lighting of the numerous large chandeliers overhead. Gone too is the musty smell of old books on wooden shelves and the hushed atmosphere where anything above a whisper drew disdainful looks from other patrons or, worse, a stern admonition from the librarian. Now the library is a place of children’s story-telling groups, book-club discussions and computer training sessions. While digital text on computer screens is a mark of the instantaneous gratification of our technological age, it’s a poor alternative to holding in your hand a clothbound description of Caesar’s army wintering in Gaul or Machiavelli’s reportage of cutthroat Medici politics in Renaissance Florence or Darwin’s first-hand observations of what he saw in the Galapagos Islands that sparked the idea for natural selection. Lucky the person today who can lift down a copy of Melville’s Typee from the shelves or Bacon’s Novum Organum. On the other hand, there are four shelves with multiple copies of multiple novels by Danielle Steele, if you are so inclined. Libraries have become information resources, efficient, powerful, relevant, but coldly impersonal. Scents and aromas are strong bridges to my past:

. . . soft pretzels from the local pretzel man pushing his two-wheeled

cart down the street. . . cinnamon buns, rich and gooey, from

Buccella’s Bakery on Sunday mornings after church. . .

tomato gravy simmering for hours on the kitchen stove. . .

And so are people: Miss Pappas, my first kindergarten teacher who was short and had long, curly, dark hair. Are you ready? she’d call with a broad smile as we sat on pillows on the floor in front of the piano. Yes! we’d shout in unison. Are you ready? she’d repeat even louder before suddenly swirling the large purple cover off the piano like a matador before a charging bull and tossing it on top our heads amid our joyous shouts. I like to think that seeing us at the very beginning of life’s journey, Miss Pappas was helping us build a storehouse of laughter to draw upon in later years when laughter would not always be so easy to come by.

When Miss Pappas left in the middle of our school year, for what reason I have long forgotten, Miss Paine took her place. She was a tall, thin, older woman whose straight silver hair should have warned us that she was made of sternness and that her main concern was to impose order and discipline on us. Miss Pappas wanted to hear us laugh; Miss Paine wanted us to obey.

And there was our neighbor, Mrs. van Rankin, the elderly woman who refused to give back our baseballs and footballs and anything else her ivy-covered yard swallowed up, as if by collecting things from our lives she could fill the voids in her own. As much as we resented her keeping our things we knew she was a widow who lived alone and so our resentment was softened with a degree of sympathy.

60 years later the smell of pancakes on the griddle takes me right back to the pancakes my mother would have waiting for my brother and me when we came home from school for lunch on a winter day. Rose-colored tiles in the mosaic of my youth.

•

Harry’s candy store sat at the corner of Opal and Porter Streets. I had to pass it every day on my walk to and from St. Monica School. Harry Wolf was a small man with a bushy gray mustache and salt-and-pepper hair combed straight back from his forehead. Edith, his wife, was even smaller with thin dark hair that came to just below her ears and parted in the middle like the photos of women in the late 1870s. Both dressed in dark clothes, Harry in dark flannel shirts over which he wore a gray sweater that buttoned up the front and Edith in a long dark skirt that stopped just short enough of the floor to reveal her black brogans. With their austere clothes and perennially suspicious nature they seemed the visual manifestation of some dark east-European past full of haunting ghosts and nameless fears carried with them across the ocean like heavy suitcases. In my memory, neither one of them ever smiled or asked me about school as other storekeepers often did.

Only now as I look back the thought comes that as Jewish people they might very well have been refugees from the rising terror that was beginning to take hold in the Europe they left behind and that this fear and suspicion were chains that bound them everywhere they went. Whenever friends and I went in the cave-like store either Harry or Edith would appear out from behind large display cases, sliding silently into view like cardboard figures in a shooting gallery to watch every move we made. I could feel their eyes following me as I lingered in front of the candy displays trying to decide what I wanted, their faces growing harder and more impatient the longer I took. It was probably no more than what any prudent store owner would do, particularly when the majority of your customers are school children just released from seven hours in the iron grip of the nuns. But I never felt comfortable or at ease in their store. They were willing to sell you the candy or bubble gum you came in for, but I always had the feeling that they were just as happy to see you leave. Still, in the eight years I passed Harry’s four times each day, I braved their suspicious gaze to trade hundreds of nickels for Milky Ways, Three Musketeers, Snickers and packs of five baseball or football cards that came with two rectangles of stiff paper-thin bubble gum.

South Philly. . . a furtive candy seller and his equally furtive wife. . . summer nights on corners with friends. . . freedom and joy and lack of responsibility…and death.

The first dead person I ever saw was Mr. Brody, the father of one of my classmates. I remember the nun leading the entire class to the funeral parlor across the street from the school to view the body and the uneasiness I felt realizing what we were going to see. My experience of death up to that point had been limited to television westerns where men were always getting shot and killed. . . maybe that’s how it would look. I could handle that. Then we entered the room with its subdued lighting, its heavy draperies all around and the almost choking smell of flowers and there was Mr. Brody in his coffin, his wife and my classmate standing by it crying, and it was nothing like the TV deaths I had seen. Here was undeniable proof of the enormous gap between make-believe and what I saw lying there in front of me. No TV actor was talented enough to portray that difference. Something huge and vast and deep and real was missing from Mr. Brody’s face, some spark that was the difference between a human face and a wax mask. There was a stillness and an absence unlike anything I had ever seen. I had never known Mr. Brody alive and to this day he remains for me that gray body lying there, more motionless than anything I had ever imagined, amidst a suffocating odor of chrysanthemums.

But I did know Jerry. He was three or four years older than me, one of the “big guys” in the neighborhood. Unlike the other guys his age who made a practice of either torturing us younger kids or ignoring us completely Jerry always treated me as his equal. He was never too important or too cool to throw a football or baseball with me, shoot baskets or just talk. The story we heard was that he had been sitting in the front seat of a car while another guy in the back seat had been playing with a gun. It discharged accidentally and the bullet entered Jerry’s head behind his ear killing him. I remember him too in his coffin, and I became aware for the second time of the vast chasm that separated the living from the dead. It was Jerry’s face, that much I could see, but the difference was staggering. Even more than Mr. Mindy, the finality of what was in front of me was terrifying. There was nothing in the body that lay there in that red velvet casket of the strong athlete who tossed 30-yard passes to me on the street or drove powerfully toward the basket for a lay-up. There was only a suit of clothes laying there that looked as if it had been stuffed with tissue paper. With Mr. Mindy death had seemed, if not expected, at least not inappropriate because of his age. Jerry wasn’t even 20 years old. If I hadn’t known it before I learned that day that death paid no attention to age. •

Images created by Barbara Chernyavsky.