I park my scooter and enter the office of the collective taxi station at Pointe Simon. The smiling black receptionist with the straight hairdo and metropolitan French accent tells me, politely but insistently, that she prefers I actually meet with one of the social workers before being issued the application form. She gives me a number, and I take a seat — among the host of black single mothers.

Interminably, I wait for my number to come up on the screen above. At first, I calculate that I can safely absent myself for 30 minutes, given the delay between numbers called and my own 124. But the numbers seem to jump erratically — in no time at all, 125 flashes across the screen. There is nothing to do but eavesdrop on the two women speaking Creole behind me. They are in agreement about the bad behavior of some nine-year-old kid — “he’s almost ten already, he should know better.” Complaining — be it in the tongue of Molière or the abbreviations of Creole – is de rigueur in the Antilles.

Thus, have I entered one of the sacrosanct institutions of the French overseas departments: the Caisse d’Allocations Familiales, familiarly known as the CAF, part of the ubiquitous welfare system of la République. Just for having children, the French state gives you money. My children are French; we are entitled to apply. But even to pick up an application form, you need to wait 45 minutes.

Never mind that I am not French. In the overseas departments, unlike in metropolitan France, the man is automatically, officially, the head of the family. Even though it is my wife who is French (and Martinican), and it is she whose bank account will be fattened by the child payments, I, the man, must apply as head of household. “Oh, there are many differences with France,” the social worker explains to me. “It is 7,000 kilometers away.”

At first, Jenny Bouton (they need to wear identification badges, these days) is skeptical of this new client. On this all-so race-conscious island, after I tell her that my wife is from Martinique, she seeks precision. Pointing to her left forearm with her right hand, she asks, with just a tad of discretion, “Elle est brune?” Now, for a civil servant performing official business to ask about the skin color of one’s spouse is, by American norms, scandalous. It may even be legally “actionable.” But to limit one’s reaction to outrage would be to miss the more important point. For Madame Bouton did not ask if my wife was black: that might have been offensive. As long as I hadn’t taken a béké (that is, an indigenous member of the white aristocracy) as my wife — a fact that would have certainly stiffened my rapport with Mrs. Button — then the socially correct assumption was that my wife’s color would, like her own, be brown. Not black, like the majority of the women in the waiting room with whom she ordinarily would be dealing.

We then spend the next 45 minutes chatting about New York, with which she is very familiar. A sister of hers has lived in Queens for many years, and Jenny has gone to see her many times. (Perhaps because Jenny’s own husband died 17 years before, a fact that the social worker revealed in passing. When I express my condolences, she replies philosophically: “We have to lead our lives. What can one do?”)

And so she nostalgically invokes the subways, Flushing Avenue, the cleanliness (compared to Paris – no pooper-scooper dog walkers there), even the discipline of the pedestrians (must have been during Rudy Giuliani’s pre-Trumpian crackdown). She waxes rhapsodically about the freedom, about the opportunity, about the work ethic. By way of the downing of the Twin Towers, the conversation turns to Middle Eastern politics: “Here, people like to put the Palestinians on a pedestal. They, too, are also an undisciplined people. We even had a social worker here, a Syrian. He was so undisciplined they finally had to let him go.”

Every so often our conversation is interrupted — with apologies — by the metropolitan French-accented receptionist. Clients have returned with documents that were either superfluous or incorrect. The receptionist is obviously new. “Elles racontent n’importe quoi,” Madame Bouton pronounces dismissively.“They’ll tell you anything.”

“But what do I do with the document,” the earnest receptionist persists. “Oh, just accept it and put it aside,” her supervisor replies vaguely, wearily. This is the daily stuff of the Family Allocation Fund of Martinique. Dealing with a New Yorker is not. She is eager to continue our conversation.

“Ils sont fainéants ici. Martinicans are lazy. They don’t want to work. They just prefer to live off of the Family Allocation Fund.” She doesn’t share the ironies that I acutely feel: that I, an American professor of comfortable means, am also applying for a piece of the FAF pie; and that she, the servant of the state, is now spending her morning bantering about the world and criticizing the laziness of her compatriots.

“Ce n’est pas le paradis ici,” she sighs. “Maybe it once was a paradise. No longer. There was a time people would leave their homes wide open. Now, the thieves are everywhere. My own mother went to mass one Sunday at eight and by the time she returned at ten, her home had been turned inside out.”

“Who does such a thing?” I ask in mock shock. “Martinicans?”

“Of course! What do you expect? There are gangs of delinquents that you can do nothing about. They shoot crack. I had a boy come in here to complain about his mother. His own mother! He says he is HIV-positive. I tell him he needs to go to the hospital. Such a person should not be walking about, in the streets with everyone else.”

Having spent half my morning at the FAF, already, I don’t know how to extract myself. But it’s getting close to noon: sacrosanct quitting time. Sensing the need to conclude our “business,” my technicienne sociale reviews the documents I need to submit with my application. She throws a curve: “You need a photocopy of your titre de séjour.”

“What is that?” I ask in all innocence.

Now it is her turn to show surprise. “How is it that you are here? What papers did you show to enter Martinique?”

“Mon passeport.”

“Surely, you know about titre de séjour at school.” I remind her that I never went to school in France.

“You need to go to the prefecture. There, you apply for your residence permit. Only then can you process all your administrative formalities.”

I take my leave, expressing my happiness that we have had the opportunity to meet. We shake hands, and I remount my motor scooter, feeling foolish in my quest for French state family allocations. But the phrase that sticks most in my mind, as I plunge into the traffic jam of Fort-de-France, is the one that Madame Jenny Bouton, in summarizing the state of her native country did not finish. “Il fait chaud, oui mais . . . We have warm weather all the time, all right, but . . .”

Paradoxical Polities

In the post-World War II exuberance of decolonization and Third World independence, many corners of the colonized world were overlooked. Small, insignificant, and anomalous, it was assumed that these societies too, one day, would constitute their own governments and join the United Nations. True, there were the exceptions of holdover colonies — the Angolas and Rhodesias of Africa, the Anguillas and Antiguas of the Caribbean, the Samoas and East Timors of the Pacific — but these anachronistic polities were also to prove the rule and ultimately achieve independence. History so dictated.

In the case of the French Empire, however, there are exceptions that continue to be overlooked. Is it because they insist on defying an otherwise ineluctable historical process? Is it because France has long refused to even imagine weaning them? It is not for lack of attention or publicity that these islands are so misunderstood; over the years, tens of thousands of Americans and Europeans have traveled to them, staying at Club Meds and other resorts and regaling their friends about visiting a French “colony” (which, technically, they are not) or having seen the home of the island’s “President” (a position which does not exist). These societies are misunderstood not because they are unknown but because they do not fit any familiar or normal pattern: their inhabitants, descendants of slaves and indentured laborers, decry colonization but eschew independence. They are tropical anomalies, paradoxical polities.

Take the island of Martinique. More than seven decades have elapsed since France passed in 1946 the “law of assimilation,” transforming this French Caribbean island overnight from the colony into — presto! — a département, a state, an integral part of the French Republic. A quarter of a century later, the surrounding islands — Barbados, Dominica, Saint Lucia, Saint Vincent — began to take their sovereign seats in the community of nations. Yet Martinique (together with mainland cousin, Guiana), has (even if she has technically changed her status from “department” to “territorial collectivity”) remained “an integral part of the French Republic.” Whether she is considered an Overseas State or Territorial Collectivity or Disguised Colony, one thing is certain — she is an island whose mostly Black population still “belongs,” in one sense or another, to the Republic of France.

Skin Color and Race

Yves hosts a late-night radio call-in program called “Partners.” Singles (usually middle-aged or elderly seniors) in search of a mate call in to describe themselves, their interests, their ideal partner. Skin color is a major factor, and there is no beating around the bush about it. “Not too dark,” is the common refrain, describing both the caller and the epidermis of his or her preferred partner. Yves remarks at my surprise about the openness of the color question.

“Skin color has always preoccupied the West Indian,” he says. “There’s no hesitation about expressing it.” Less important than the consciousness of color is the difficulty of connecting.

“There is a common expression in Paris,” says Yves, summarizing the frenetic lifestyle there.

‘Métro, boulot, dodo” — subway, job, sleep.’ Well, there’s no subway in Martinique, that’s true, but the rest is the same — work and the stress that goes with it is all-consuming here. You get home at the end of the day, all you want to do is crash. There’s really not much difference anymore between Martinique and the Metropole. That’s why my program responds to a need. It’s so much harder for Martinicans to meet each other these days.

Personal ads give an even wider choice of the racial, physical, and cultural preferences of men and women searching for mates. “Beautiful mulattresse, 38 years old, 1 son, seeks West Indian man, 30/46 years, 1.79 meters tall, slim, serious, affectionate, honest.” Or: “Martinican Man, Catholic, single, 39 years old, 1.66 metres, slim, salaried, seeks beautiful, slim, Martinican, Metropolitan or Indian woman, free, salaried, without children.” Some deviate from conventional color stereotypes: One “very light-skinned” man (but, one reads between the lines, not exactly white, either) advertises his preferences for a “rather slim and very brown woman.”

Female islanders are not shy about connecting with white men: “Woman seeks Metropolitan man — single, well-off, not fat . . .” Others express more sophisticated tastes: “Big, young, 48 year-old mixed-race woman, with charm and class, smiling, very well educated, professional, wishes to meet Metropolitan man, 45-52 years, free, big, nice, sharing with her a desire to share a beautiful story in which each one will freely give, will be tolerant and sincere.” Another “charming young West Indian woman of 30 years, big, without children, dynamic, head on her shoulders” has her mind set on a “Metropolitan man of 35-40 years, big, mature and responsible, to share tolerance, frankness, dialogue, and tenderness.” Older women are not shy, either: “West Indian WOMAN, retired, having lived thirty years in Paris, seeks Metropolitan companion 60/65 years, to share fun times, outings and more, if affinities.” If you are an educated and non-violent “European or North American type” of guy, you might wish to contact that special “big, 32-year-old West Indian young woman” who is “dynamic, very friendly, respectful and tolerant” with a wonderful “personality and sense of humor” who is at the same time “sensible and sentimental.”

White men from France are not shy about reaching across the color line, either: “50-year-old Metropolitan seeking young, slim, sexy woman to make a good couple.” Another Metropolitan man (of indeterminate age but “physically agreeable and with a good job”) — describing himself as “elegant, cultivated, sweet, sentimental, balanced” — explicitly seeks a “West Indian woman between 30-40 years old possessing charm and personality to share humor, fidelity, complicity.”

Occasionally, a white French woman will advertise her openness to dating a West Indian man. (One 52-year-old “dynamic civil servant,” for example, will not exclude any color if the man is “free, serious, and with a good general culture.”) Nowadays, one even can see a “bisexual young mulatto woman” advertising for a female mate; or a “cool, pleasure-loving” Metropolitan man looking on the island for another man (18-22 years) . . . But never does one see a West Indian man advertising for a Metropolitan woman: it is the one ad guaranteed to fail.

Despite the spatial distance, cultural distinctiveness, ethnic separateness, and relative impoverishment, the nation’s government insists that its black islanders are no different than the rest of the country. In the face of sociological absurdity, it insists that her faraway black citizens, scattered on islands in distant seas, are in law and soul essentially the same as residents of that country’s capital. Bombs occasionally explode, people sometimes die, independence is periodically demanded. But the Metropolis insists that the islands are no different from the Mainland.

Martinicans working in the hotel business (waiters, barmen and women, beach attendants, etc.) have had an unfortunate – but in too many instances justified — reputation for surliness. The attitude is less one of helpful service than sullen, reluctant, duty. The typical explanation invokes the familiar colonial slave complex: “Surliness to white tourists is a reaction-formation to a plantation mentality.” But take a vacation in nearby Barbados, where slavery had been as firmly institutionalized, and which was a colony 20 years longer than Martinique (until 1966), and your meals will be brought with a smile, not a scowl. No, the attitude in the Antillean hotels is of more contemporary origin. Throughout the service industry, one is not thought to be paid for performing a service – one is just paid. And paid well (at least by Caribbean standards). Service is a favor rendered by the employee (ditto for civil servant) whose salary is guaranteed, no matter the spirit in which the deed is performed. If a patron or client doesn’t like it, tant pis — employees cannot be easily fired.

This is France, after all, regardless of tropical location. Strikes are recurrent, unions are quick to cry “exploitation.” A hotel is no different from a post office or an airport bar. Nobody tells a worker what to do — Metro or Martinican, tourist or resident. Any such insistence or complaint on the part of a white will invariably be rejected as another example of neo-colonialism and racism. “I am not your slave!” a Martinican bus driver haughtily rebukes a white pedestrian he refuses to pick up. A hotel guest expecting his bags to be carried to his room may be similarly rebuffed. Whether the reaction is suppressed racial mutterings or horrified liberal guilt, the outcome is the same: the suitcases remain in the lobby, and the pedestrian is left on the road.

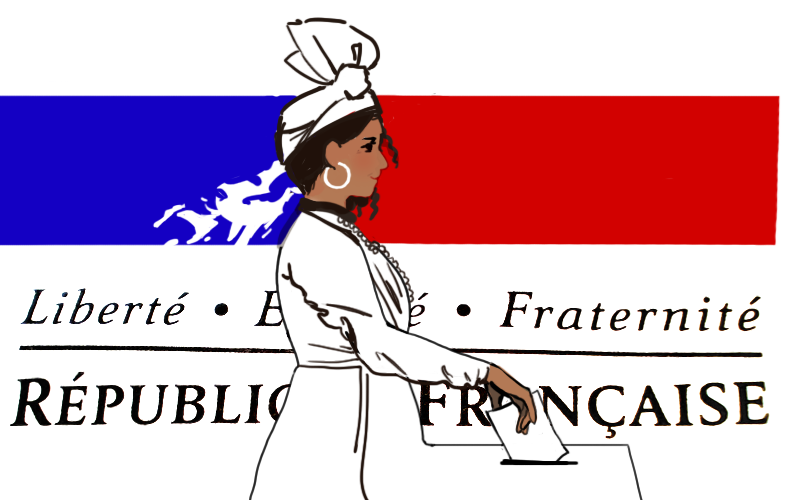

Voting in Paradise

You don’t usually associate jaunts to the Caribbean with voting. But if you drop in at the local precinct when the islands go to the polls, you might be in for a pleasant surprise.

Every fifth springtime, France elects her president. This electoral calendar applies no less to her far-flung tropical outposts, from Tahiti in the South Pacific to Guiana in Latin America. Lolling on Martinique in April and May when la Constitution called for les présidentielles, I was still basking in the Antillean sun when les législatives rolled around in June. Since choosing both president and legislator is a two-round affair in France, I was privileged to view Martinicans cast ballots no fewer than four times. Unexpectedly, and with great pleasure, I came to play an official role.

Voting is both a solemn and festive occasion for French West Indians. Women, especially older Creole ladies, put on their finest dresses and don their most fashionable hats. Men, too, dress up to vote, often wearing their Sunday best. Indeed, a good many Martinicans go directly to their polling station from church. Since islanders are generally camera shy, the voting day offers an unusual opportunity to capture them on film in their sartorial best.

As the polls closed at six o’clock on Sunday evening in the town hall of the sultry capital of Fort-de-France, the elegantly dressed and exquisitely perfumed head of the voting station sauntered up to me and asked if I would serve as scrutateur, an official vote counter. “Bien sûr,” I replied, out of politeness, “only I am not a citizen of France.” She smiled, and wordlessly gestured for me to take my place alongside the other scrutateurs.

The process is straightforward and not subject to a possible dispute. All the dignified townsfolk had, in the privacy of a curtained voting booth, placed a preprinted ballot in an envelope. Then, at a table manned by local electoral officials, they then dropped the envelopes into a voting box. The head electoral officer declared aloud in French, “Has voted!” Our task as scrutateurs was to make piles of the envelopes, one per candidate, and count them. We did so seriously and scrupulously but also with banter and bonhomie.

There was no room for confusion, doubt, or discretion. No chads, hanging or pregnant, as in the Bush-Gore fiasco in Florida. No finger-sensitive computer screens, slow to boot up or quick to screw up. We counted, double-checked, and reported the results in writing. The entire process took us only about an hour. When we were done it was even appropriate (this is France, after all) to kiss the pretty president of the polling station — on both of her cheeks, of course.

I spent one of the other voting rounds in Vauclin, a seaside village on the southeast coast. A slim, elderly man of café-au-lait color, wearing starched white shirt and tie, saw my camera and requested, in Creole, that I snap his portrait. Good citizen that he is, Monsieur Gaujon had descended from his hilltop home on Mount Vauclin to cast his ballot. Several weeks later, when I track down his whereabouts to give him his photo print, I see from his own framed pictures that he is a war veteran.

Monsieur Goujon’s wood-framed house is small but tidy, cordoned on the outside by a chicken coup. Given the mid-day hour and serpentine road I had cautiously driven to find him, I demur from the ‘ti punch rum shot and accept a glass of wine instead. He lives alone. Making his way down from his island summit to vote in France’s elections would have been a major social break from Monsieur Goujon’s day-to-day country life.

As I reflect on America’s compromised elections — selective voting suppression of our African slave descendants, Russian hacking on a national level — I think back to the ballot-casting in Martinique. America’s electoral problems are not merely mathematical (“Why can’t we count straight?”). It is also existential. As Americans, we focus on ever-more technological solutions, forgetting that human interaction has also been part of our national civic exercise. During my brief bout as guest scrutateur, I learned that counting ballots by hand is a bonding experience. It can also be merry. In low-tech voting, we do not merely physically recreate democracy. We reconnect as citizens. Even though it was not my election and not my country, as an American I felt in my bones the buzz of democracy.

Call it “election tourism.” In any event, it is a great way to peak behind the scripted façade of island life. And if you’re lucky, it can even net you a soothing glass of noontime rouge, or a civic-minded (but no less head-spinning) French Caribbean kiss. It certainly provided me some well-appreciated positive French West Indian vibes.

Ivory Tower on the Island Paradise

Perched on the heights of the commune of Schoelcher, overlooking the Caribbean Sea, beckoning with a giant statue of metallic faces (are these the “White Masks” of Frantz Fanon fame?) lies the University. A hotbed of radicalism, social leftism, and political independentism, the University of Schoelcher — named after France’s preeminent abolitionist — is entirely funded by the French Government. Students pay a nominal fee for registration and are entitled to cheap rent dormitory accommodations. There is a cafeteria, an amphitheater, tennis courts (lighted, for night play). The library houses a respectable collection of books and journals but in its daily operation demonstrates how little seriously academia is really taken here — the doors close firmly at 6:00 p.m. Studying, it would seem, is a daytime activity; the evening is too important for mere book learning. (In its favor, at least the University library doesn’t close for the mid-day siesta — as does the public library in the capital).

Lovely young Creole women arrive for classes dressed as American coeds would for a school prom — flowing (or slinky) dresses, high heels, make-up. The men may be slightly more cool as the French say (the French don’t let their America-borrowed slang fade into obsolescence so easily), but even in their tee-shirts and jeans tend to stay à la mode. Nobody pays attention to the cows which graze on the campus lawns. University walls are graffitied with slogans denouncing colonialism (French), imperialism (American), and fascism (international), as well as calls for a boycott of all elections. But there is no damper to the rambunctious zouks (Creole-style mixers) that may blast from the dormitory at night.

A few paces from the campus is a prairie, now claimed by the university, on which a few cattle graze. An elderly Martinican man holds court there, wearing a khaki outfit and an old, colonial-style pith helmet. He is milking his cows, lulling them in the secret language of the herder. With the leathery thumbs and forefinger of his right hand he pulls and strokes an udder; with the left hand he fills a glass bottle, squirt by jerky squirt. Now filled with warm, milk the bottle incarnates the ultimate Antillean syncretism: “NOILLY PRAT,” reads the worn label on the herder’s bottle. “Extra-Dry Vermouth (Made in France).”

In Creole, the old man recounts to me how he spent most of World War II in a prisoner of war camp in Germany. (As with many in the French army, he was taken prisoner early on in the War). It was cold, he said, too cold; but he did see some very large, and very fat, cows while he was in Europe. University firebrands cannot relate to him as a former P.O.W. in war-torn Europe, even if he represents the authentic Martinique they pretend to ardently defend

For the old Creole herder, the university represents grazing land that is no longer. He knows not what transpires in those air-conditioned buildings, what polemics are raised, what radical chic (in a Creole he is trying to transcend) is proclaimed. He does know, though, that he won’t get any more milk from this college site.

In the end, though, I do manage to navigate the French welfare system and, as a parent of French citizen children, milk it for all it is legally, post-colonially, worth.

Postcolonial Bellwether?

Multiple postcolonial paradoxes permeate the French West Indies. Together with the South American jungle of French Guiana and the Indian Ocean outpost of Réunion Island, Martinique, and Guadeloupe constitute vestiges of an empire that, on the eve of the Second World War, reached four continents, spawned over 12 and one-half million square kilometers, and numbered 69 million subjects. Once known as the “Old Colonies,” Frenchmen now whimsically refer to them as the “confetti of the Empire” or the “dancers of France.” Even Charles de Gaulle once (in)famously called them “a few specks of dust in the ocean.” Once an experiment in liberal decolonization, more radical leftists have come to see them as “the crowning point of French colonialism” — colonies that are not even conscious of being colonies. Navigating for centuries between the shoals of resignation and rebellion, between assimilation and liberation, has turned Martinicans into French-speaking masters of Caribbean ambiguity. In an era of reactionary nationalism and hostility to the racial and ethnic “Other,” how these islanders adapt may be a bellwether for minorities even on mainlands, in the Europe where they are citizens as well as the Americas where they live.

Images illustrated by Barbara Chernyavsky.