40 years ago, The Clash released their third studio album, London Calling. A masterpiece in experimentation, London Calling is one of the most ambitious, musically sprawling albums of all time. The album comprises 19 tracks, featuring punk, garage rock, rockabilly, reggae, ska, R&B, and even jazz. Upon its release, it exploded the conventions of punk, defied categorization, and deftly blended musical genres along with politics and irreverence. In the Rolling Stone review of London Calling, the album is referred to as “so rich and far-reaching that it leaves you not just exhilarated but exalted and triumphantly alive.” I can say, without exaggeration, that these were exactly the feelings elicited when I first discovered The Clash in high school. I had survived my early teenage years, and I was working the Seattle-fueled angst out of my system, moving my musical preferences a bit further down the coastline to explore Bay area punk. I was hooked by the frenetic energy of bands like Rancid, Green Day, and Operation Ivy, but it wasn’t until I saw the John Cusack movie Grosse Pointe Blank that I encountered the Clash. I saw that movie four or maybe five times in the theater, and each time I was completely transfixed by the backing soundtrack, and particularly the song “Rudie Can’t Fail.” There was something about the boisterousness — and maybe even a little bit of dangerousness — of the song that was infectious, and it was the gateway to the exhilaration I would come to feel for the entire album.

London Calling became the soundtrack to my commute in high school, a mainstay in my college-years musical rotation, and the inspiration for me to study political theory in grad school. Given the sonic breadth of the album, it has always found a way to reflect my mood: for righteous political indignation, switch on “Clampdown, “Spanish Bombs,” and “Death or Glory;” for the gloom of suburban alienation, take comfort in “Lost in the Supermarket” or “The Card Cheat;” for when I am just feeling amped, crank up the title track, “The Guns of Brixton,” and “Wrong ‘em Boyo;” for when I just got dumped, turn on “Train in Vain” (on repeat); and, of course, “Rudie Can’t Fail” unfailingly pulls me out of whatever bad mood I might be in. The album has been an anchor for me, and as 2019 unfolded, I wanted to find a way to commemorate it and think about its relevance to a more contemporary audience.

Fortunately, I found a way to do this through the Pennoni Honors College by teaching a Great Works course. The purpose of such a course is to celebrate, explore, contextualize, and gain a deeper understanding of a singular work that is considered to be of unique significance in its genre — for me, this was London Calling. Throughout the term, we explored the historical context — in terms of music, politics, and society — in which the Clash formed and created London Calling. We learned about its origin story, and compared it to other punk staples of the time. We dissected the album track by track. We discussed the aesthetics of its famous cover art. And, we considered how the album was received at the time of its release, as well as how it has aged over the course of 40 years.

When it came to thinking about how the album has aged, and how we assess it as a great work, the students in the class were tasked with writing a 40th anniversary review of London Calling. This was certainly no small task given the amount of praise that has been heaped upon the album over those 40 years. Saying something new or having a fresh take might have proven difficult, but in some ways these students had the advantage of bringing a distinctive perspective precisely because this was a fairly unknown album to them (although many did note that they took the class because their parents are big fans of The Clash). My hope was that the album would spark the same exhilaration that I felt; that it would leave them feeling “triumphantly alive.” But, what follows demonstrates some of the unique insights they developed along the way. It is clear to me that London Calling still resonates today with a new audience, and I think its ability to endure over time, often in unpredictable ways, is what makes it a great work. I think that my Oldsmobile tape deck would agree.

Dr. Kevin Egan, Director of Academic Programs, Drexel University

Sofia Tanvir (BS/MS medical engineering,’21) – “Between Blurs”

Joe Strummer, the lead singer of The Clash, was frustrated with the crowd’s lack of rage at The Palladium in New York City on September 20, 1979. Despite the band’s incredible energy, Paul Simonon, the lead bassist, was caught raising his guitar and smashing it to pieces when he saw stage security pushing the fans to sit down. His body is fully immersed in smashing: legs splayed in a makeshift squat, hands gripping the neck like a battle-ax, and his head down. His face obscured, he stands in for rage-filled youth — the embodiment of “I’m mad as hell and I’m not going to take it anymore.” This image then became the iconic cover of London Calling, an album that would alter the landscape of popular music forever.

The blurry picture captured by accident demonstrates the band’s desire to make an impact. The literal visual of a guitar’s imminent destruction symbolically represented the destruction of norms they set out to smash as punks with a lot to dismantle. They weren’t the type of band that actively sought money, fame, or groupies. Instead, they were a band whose core values were rooted in consciousness-raising and social change. Joe Strummer, a committed socialist, protested against monarchy and aristocracy, which resonates throughout the album as the band decries fascism, racism, and capitalism. The band did so without relying on overtones or sly winks and nods; their politics were explicit. Even 40 years after its release, London Calling has kept its electricity.

In “Death or Glory,” Strummer bellows, “Death or Glory, just another story.” Both blasé and critical, the refrain is repeated as both warning and curse. The song opens like a Rolling Stones track, a bit of a meandering thump and beat, before adapting into the brash reality of The Clash’s rhythmic thrashes. The style is reminiscent of the content itself — of former hellions becoming saints once given access to the comfort of capitalism. The choice, that of death or glory, is provided to artists — record contracts, Hollywood film parts, museum acquisitions. The Clash, however, prioritized creative freedom, agency, and independence above all. The Clash provided perspective to those using punk as an aesthetic or trend. “In every gimmick hungry yob diggin’ gold from rock ‘n’ roll.” Lambasting those who treat punk as a gimmick, The Clash, began to define punk not as a fashion or simply an art form, but as a movement. A movement concerned with actual issues like poverty and racism. Bands not identifying their politics, became shills, regardless of whether they looked or sounded the part. The Clash wanted unity, even if rioting and destruction was the way of getting there. Paul smashed his guitar not to cause mayhem, but to bring people together.

Even after an amazing show at the Palladium in New York City, Paul still needed to add some sort of rage. He became a symbol for speaking your mind and protesting against things that you don’t agree with. The Clash was trying to warn people that no action will result in unhappiness. Their consumption with idealism and failure is repeated in their song, “Clampdown.” Living as philosophically punk was difficult. It requires, as illustrated above, a refusal of the pleasures associated with capitalism. Doing what is expected, going through the motions, dedicating oneself to societal norms, to The Clash, was the easy way – to stand for something higher that went against “the clampdown,” was a challenge. Punk was a status earned not purchased. The Clash wanted people to live a life worth living especially during their younger years. They were a wakeup call, not only to the musical industry, but to people as a whole.

Their legacy lives on and as different interpretations arise, the underlying message remains the same. Enjoy your youth and fight for what you believe in.

Niayla-dia Murray (BA philosophy, BA political science ’20) –

“The Clash’s Sound Cloud”

It is not daring at this point to call London Calling influential. It has been listed multiple times on critical “best of” lists. Songs from the album have been frequently cited and sampled. Bands continually include the band and Calling as inspiration. The band’s influence is far-reaching, but we typically only consider the aesthetic — the visual reference of Billy Joel Armstrong as a modern-day Joe Strummer or the sampling of “Train in Vain”’s drum beats and Garbage’s “Stupid Girl.” But the band’s dedication to punk’s DIY sensibilities and willingness to play, open up more paths to explore their far-reaching influence. Their use of reggae, dancehall, rockabilly was just as political as their content, articulating music’s potential to cross borders and inspire change.

Lil Yachty, Machine Gun Kelly, and xxxTentacion are probably not names you hear alongside The Clash or perhaps at all. They are, however, artists who have deviated from what is considered to be “standard” hip hop by adding other elements into their music styles and doing so outside of the constraints of the recording industry. Their hip-hop is punk. They are playful in their lyrics and sound, started producing and distributing their own content, and cultivating their music and image outside of the industry.

When punk was born in the ’70s, punk bands self-produced their albums and distributed them through small independent record labels. Sometimes they would create their own music label to distribute their music. While technology may have changed, the tactics of making and distributing albums outside of the exclusive mainstream music industry have remained. Many have access to computers or cellphones that allow musicians to record, produce, and distribute music. Newer hip-hop artists will tell you they began their music career by creating music and distributing it through social media platforms. There are have been numerous artists who have all found success on sites like SoundCloud and Bandcamp. Their music sharing capability via the internet has allowed artists like Post Malone, Lil Uzi Vert, and Travis Scott to reap success. Self-production and self-distribution on the internet mirror the pre-Internet punk music scene.

Punk was a force to be reckoned with when it first emerged, but everyone knew punk when London Calling emerged in December 1979. It was obvious that The Clash had made an instant masterpiece that stands the test the time and would influence future music. London Calling is a punk album in its own league. It did not adhere to the strict “punk sounds” that had been continually copied and institutionalized, but for that very reason its message and impact stood out. The songs on the record were all categorized as being punk, but they easily did not fit into one genre. They incorporated sounds typical of R&B, rock, reggae, jazz, and pop. It’s a genre-merging album, unafraid to incorporate aspects of other genres into its songs.

Hip-hop has followed in The Clash’s footsteps. The early ’90s were full of lawsuits against artists sampling music from The Turtles, Gilbert O’Sullivan, and Roy Orbison (amongst others). Considering how both hip and punk have been characterized as aggressive genres, the infusion of easy listening, jazz, and folk seem to go against the grain of what is expected. Such contrasts have been further amplified with rappers who grew up in the digital enclosure have had access to content without context, where all content seems up to grabs to make into memes, like, and circulate images or videos without spending too much thought about who to credit at a more rapid pace. Whereas artists of the past were noting their influences and usually harkening to a different era, history for contemporary artists has become even shorter. On his 2010 mixtape, I am Just a Rapper, Childish Gambino incorporated a guitar sample into “New Prince” from Sleigh Bell’s “Crown the Ground,” a track that had been released the same year.

We can see the politics of the controversy played out in the recent think pieces produced debating the legitimacy of Lil’ Nas X’s “Old Town Road” as a country song. The track, which includes samples from YoungKio and Nine Inch Nails, and features Billy Ray Cyrus on the remix, indicates the politics of genre, particularly when it comes to industry practices and sales. What constitutes a genre, and music for that matter has been a constant source of tension for critics and listeners.

The Clash’s London Calling did not singlehandedly create modern hip-hop. London Calling set precedent for modern hip-hop. Both genres originated in a similar fashion, and have chosen to borrow from other genres in order to emphasize their own. When you listen to modern rappers and their incorporation of other genres into their own music, you’ll notice many of their lyrics echo general discontentment. The generic mixing exemplified by The Clash is utilized by their successors. By echoing the past in generic play, DIY production methods, and self-distribution, contemporary hip hop artists continue to circumvent and redefine what is possible – countering popular narratives about what it means to be an artist and, more often than not, a citizen. Both genres are also tied together politically. Like many hip-hop artists, The Clash was also remarking on and criticizing police brutality, challenging racism, and holding accountable those in power.

Society is being called out through different generations. The Clash set the precedent for its descendent modern hip-hop. Punk and Hip-Hop echo similar messages. Though Punk has faded from the mainstream audience, this modern hip-hop that has incorporated its stylistic queues and reiterated its social and political discontent. The next time you are listening to a modern-day hip-hop song, do not just disregard it to words you cannot hear, but listen to the lyrics and intermixed music incorporations from other genres. You’ll realize how similar it is stylistically to punk music, London Calling especially.

Stephen Hansen (Provisional BS/MS, computer science ’22) —

“Historical Legacies”

Towards the end of the 1960s, the rock industry experienced a massive musical shift. Heavy metal, progressive rock, funk, glam rock, and country rock all hit the radio waves and became successful. Despite the popularity of rock music rushing through the airwaves of American radios, ushering in a period of challenging boundaries and societal expectations, two subgenres that relied on culture critique, never quite made it popular in the States. Reggae and Punk did, however, gained momentum in Britain. Despite having limited success at the time, the combination of these two genres would have a profound impact on future musical styles, most notably influencing the genres of new wave and hip-hop/rap. London Calling, the third album by the UK punk band The Clash, is the definitive album of the punk movement. Through the lyrics, London Calling illustrates the growing tensions of the British class hierarchy and illustrates a level of political compassion that most other records lacked at the time. Musically, the album weaves together genres that on the surface look like unlikely bedfellows, developing a sound that would become synonymous with the punk movement.

Punk rock initially began as a response to the growing popularity of progressive rock and disdain towards the heavily popular, prolific playing of artists and bands such as Frank Zappa; Emerson, Lake & Palmer; and The Who. To punks, these artists represented the elite millionaires of the music industry, creating overly produced music no fan could ever create on their own. Early punk was defined by a DIY approach to making music. It centered on simple beats, basic chords, and fast rhythms ’ without the promise of being “good.” To be punk, you didn’t have to be a savant, just willing to play at all. Punk was noise. The music, unlistenable in comparison to top radio hits, was played in underground clubs as opposed to theaters, for maybe six people instead of thousands. The goal was to build solidarity, not a fanbase.

Part of punk’s success in Britain has to do with the politics of the time, but also the rapid evolution of the punk genre. Perhaps the most famous punk band of all time is The Sex Pistols, a band compromised of members who could not sing or play their instruments well. A band created and organized by brooding manager, Malcolm McLaren, and questionably more manufactured than authentic rockers, The Sex Pistols should have never been successful. The Sex Pistols’s source of success came from criticizing the political climate of the United Kingdom. Songs such as “God Save the Queen” and “Anarchy in the UK” took the anger of British teens towards the British class system and the rise of unemployment and put it in the music. Lead singer John Lydon’s snark and the band’s rebellious attitude provided something working-class British teens could cling to when faced with an uncertain future. Additionally, The Sex Pistols leveraged controversy to gain media attention with arrests, chaotic interviews, and bad attitudes. While rock music had its run-ins with controversy — shaking hips and potential links with Satan — The Sex Pistols represented chaos. It was in this disorder that The Clash could build.

After seeing The Pistols live, Mick Jones saw the writing on the wall and the opening the Pistols were opening for new sounds and approaches to music. He sought to create his own punk band. Jones recruited singer Joe Strummer from another band, and then later hired bassist Paul Simonon, not because of his playing but because of his sense of fashion. Terry Chimes rounded out the quartet on drums. The group initially began as a heavy punk band.

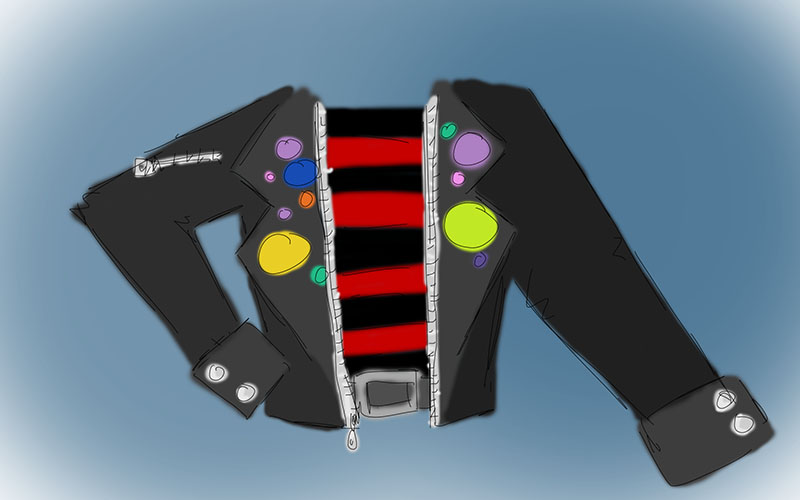

The Clash’s debut album is raw, violent, unproduced punk. At times, the band seems to play against each other as opposed to with each other, at times disorienting. Songs such as “White Riot” highlight the band’s discontent with economic classes and racism, both themes that would prevail through many of the band’s later songs. Although not yet revolutionary, the band furthered the notion of the “punk look.” Simonon’s fashion inspired the bandmates to each design their own outfits, complete with leather jackets, crude painting, and controversial patterns. The band established a “do-it-yourself” attitude that many other punk bands had at the time.

After a somewhat disappointing sophomore album, The Clash’s third album, “London Calling,” would prove itself to be the band’s magnum opus; an album which is both definitively punk in nature but also deviates away heavily from the genre. While American punk bands like Talking Heads, Blondie, and The Ramones would abandon the punk genre and message in exchange for mainstream success, The Clash dove back into the nitty-gritty nature of punk.

The success of London Calling is mainly due to its refusal to stay within a certain genre. At 19 tracks, the album consistently reflects punk themes but also jumps around genres such as reggae, ska, funk, pop, and rockabilly. This collection of diverse tracks would not be possible without the band’s second drummer, Topper Headon. Hired after the band’s first album, Headon was an excellent player and could drum a beat for any genre. Headon’s artistic flexibility gave the band room to experiment and deviate away from traditional punk beats. In that sense, Headon’s hiring is somewhat surprising; the punk bands were trying to avoid the complexity of progressive rock, and bands like The Sex Pistols hired bad players (such as Sid Vicious) because they fit the punk ethos. Headon’s hire illustrates the desires of The Clash to be bigger than punk and try new musical genres, ultimately to create their own unique musical identity.

The fusion between reggae, dub, ska, and punk on London Calling is surprising, but not unexpected. Members of The Clash like Simonon and Strummer took up an interest in reggae early in the band’s career, and the band did a cover of the reggae song “Police and Thieves” prior to London Calling. Despite being generally slower and offbeat compared to punk, reggae’s social critique helped dictate punk’s political trajectory. The Clash straddles the delicate line between appropriation and appreciation, opting to align themselves politically with anti-racist, during a period in Britain marked with racial and economic tensions. They went beyond just attending shows, as narrated “In Hammersmith Palais,” and played shows like 1978’s Rock Against Racism, to protest the surge of the National Front and racism, and explicitly critiqued racist practiced in their songs, utilizing the not only the sounds of reggae, but using the music to further amplify and critique social problems. The reggae songs like “Revolution Rock” and “Rudie Can’t Fail” on London Calling give The Clash room to experiment, but also in the political nature of The Clash, indicate solidarity between the band and the working-class African and African-Caribbean immigrants and their British born children.

In addition to reggae titans, The Clash took inspiration from previous rock artists; the punk genre itself grew from the styles of The Velvet Underground and The Stooges. The London Calling cover depicts Simonon smashing a bass (in the same vein of violence as The Who), with “London Calling” printed over in the same font used by Elvis on his self-titled album’s cover. On the track “The Card Cheat,” The Clash recreate Phil Spector’s “Wall of Sound” production technique. Additionally, during the recording process, Mick Jones used unconventional techniques such as using a bathroom as an echo chamber and recording sounds of Velcro ripping for “The Guns of Brixton.” This unconventional production calls back to the unique instrumentalization on The Beach Boys’ Pet Sounds. Although The Clash would bash bands such as The Beatles (“Beatlemania has bitten the dust” – “London Calling”) and The Who (“he’ll die before he’s sold” – “Death or Glory”), it has to be said that the band took some form of inspiration from all of these artists. For The Clash, the band set themselves to be just as revolutionary as Elvis, but also distinguish themselves from the popular bands of the ’60s. London Calling captures this evolution perfectly, showcasing both inspirations but also a unique blending of musical styles, giving The Clash their own unique sound.

The Clash and London Calling’s legacy are probably most explicitly seen in the grunge and poppier punk that emerged in the late ’90s, early ’00s. But the impact the band had on hip hop is probably the most poignant. Elements of reggae had certainly helped influence early hip hop. As was The Clash’s iteration of punk, hip hop was DIY and was geared around borrowing from the past to elaborate on contemporary problems. Notable, for example, is Grandmaster Flash and the Furious Five’s “The Message” and its depiction of New York City as an economically desolate place with little hope for working-class black families. Such hip hop commentary would continue with groups like Public Enemy. Chuck D even described the group as “the rap version of The Clash,” and even hosted Spotify’s podcast Stay Free: The Story of the Clash. Despite the media’s focus on hip hop as a genre rife with materialism and misogyny, such criticism often ignores the diversity within the genre — the choice of record companies, for example, to lean into stereotypes, as opposed to independent artists actively working to counter those narratives and speak to larger issues. Such differences echo the trajectory of rock’s shifts in the 1970s, with bands opting for the “clampdown” as opposed to working outside of the system without as much glory and fanfare.

While the punk movement was never destined for success, The Clash, through London Calling, successfully took an aesthetic and provided meaning. The ability of the band to take influence from previous artists but at the same time do their own thing and experiment with a multitude of genres highlights significant artistic growth and gives influence for other artists to do the same. With so many genres now widely available, it’s hard for any other band to have nearly the same impact that The Clash did with London Calling.

For Olivia Eife’s (BS environmental engineering ’22) breakdown of London Calling‘s tracks, check out our Instagram stories @thesmartsetmag. •