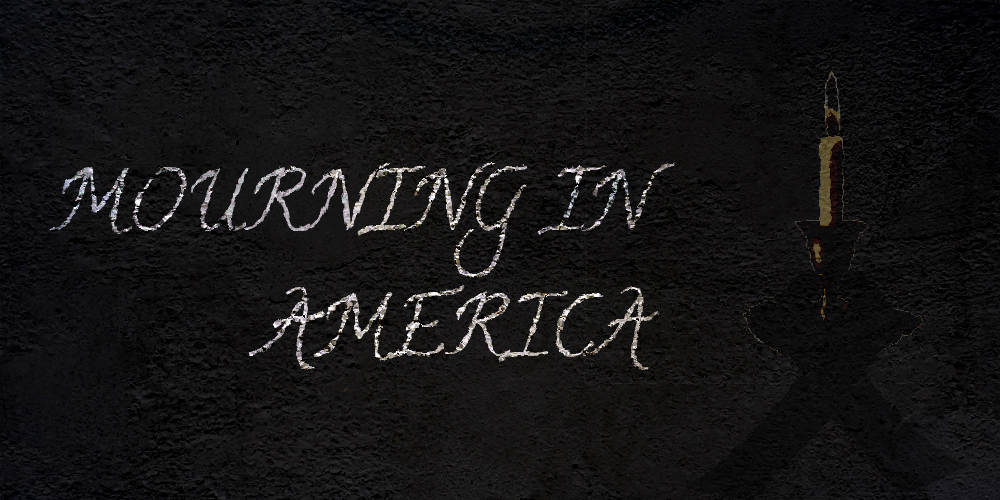

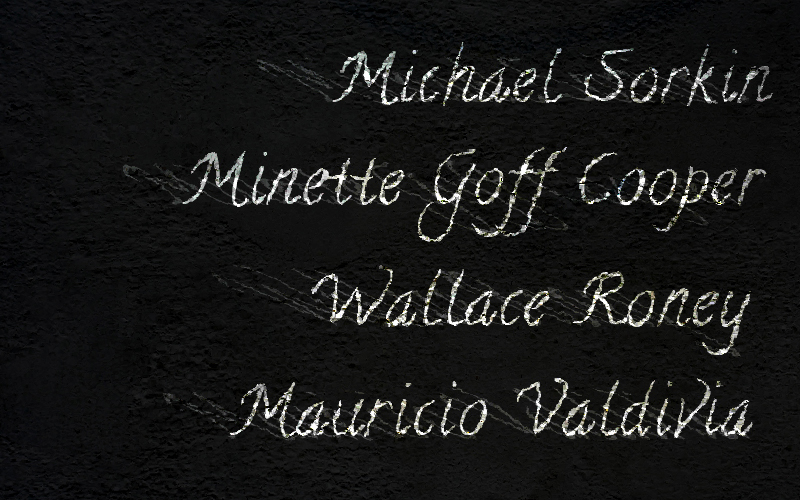

Michael Sorkin, 71, New York City, Champion of social justice through architecture

Minette Goff Cooper, 79, Louisiana, Loved big and told people she loved them all the time

Wallace Roney, 59, Paterson NJ, Jazz trumpet virtuoso

Mauricio Valdivia, 52, Chicago, Wanted everyone to feel welcome

On May 24, 2020 — Memorial Day weekend — The New York Times printed the names of 1,000 of the more than 100,000 people dead of Covid-19. They wrote: “Memories, gathered from obituaries across the country, help us to reckon with what was lost.” Within a three-month timeframe, more than 100,000 Americans had died of Covid-19 — losses greater than decades of war, from Vietnam to Iraq. In print and in a multimedia project, they printed the names of one percent of the dead and gathered information from local obituaries, creating a stunning archive of loss. It took a significant amount of time to read through all the names, which filled the entire front page. Printing all the names would have filled the entire paper.

On Memorial Day weekend, President Trump did not mention, on Twitter or otherwise, the lives lost to the global pandemic. Instead, he flouted the advice of his health advisors and walked maskless through Arlington Cemetery, tweeted about perceived enemies, lied about cases and deaths happening all over the country, and golfed. And in the weeks since Memorial Day, as coronavirus cases and deaths have continued to rise in many states, Trump continues to downplay the virus and mock anyone who tries to protect themselves and others from its wrath. On June 20, 2020, a New York Times article about his campaign rally in Tulsa, Oklahoma, said that he “claimed that Covid-19 testing was overrated and suggested that Americans were wearing masks not for their own protection, but to demonstrate that they do not support him.”

But whether or not the Trump administration accepts it, Covid-19 has killed the equivalent of a mid-size city. This absence is tangible. This absence makes its presence known not only in the usual loss of those individual people and their stories but in the act of mourning itself. In the essay fragments that accompanied the 1,000 names, the authors wrote,

This highly contagious virus has forced us to suppress our nature as social creatures, for fear that we might infect or be infected. Among the many indignities, it has denied us the grace of being present for a loved one’s last moments. Age-old customs that lend meaning to existence have been upended, including the sacred rituals of how we mourn.

The lack of proper mourning rituals during this pandemic has long-lasting effects on the shape of grief. It stymies the already-complicated grieving process and leads to more loneliness and depression for the bereaved. It is an extreme version of Meghan O’Rourke’s lament about the privatization of grief leading to pervasive loneliness. In The Long Goodbye, her memoir about her mother’s death and its aftermath, she says,

For centuries, private grief and public mourning were allied in most cultures . . . As Darian Leader, a British psychoanalyst, argues in The New Black: Mourning, Melancholia, and Depression, mourning — to truly be mourning — ‘requires other people.’

Even rituals that only last a few moments can hold tremendous meaning — both personally and collectively, they give us a space to celebrate humanness and connection, as well as create tangible landscapes of memory. They create places to sit and reflect and allow us to move forward. Rituals, like maps, museums, and history books, show us what society values.

In its Memorial Day archive of mourning, the New York Times declared that we cannot look away from this immense loss. It implored us to feel its size and scope. It also asked us to do something about it — act in the interest of the greater good, protect the most vulnerable. This archive reminded us that “They were not simply names on a list. They were us.”

•

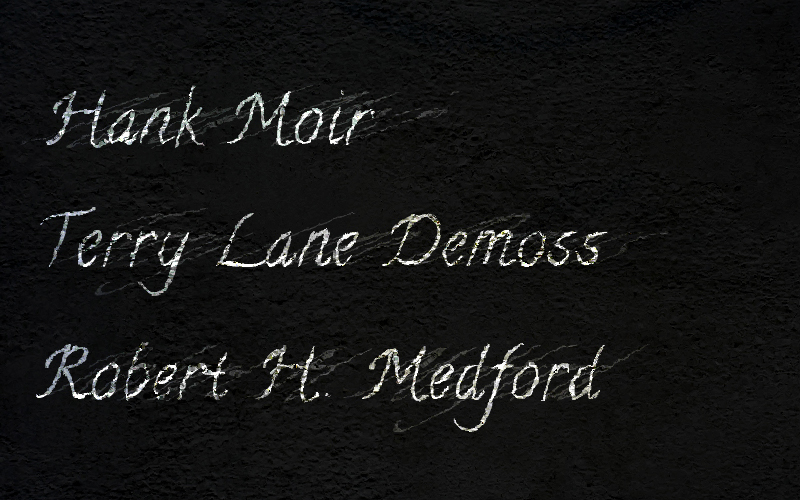

Hank Moir, 41, Unforgettable

Terry Lane Demoss, 34, Ode to Joy

Robert H. Medford, 56, Bob devotes his life to helping others

After reading the New York Times memorial, Peter Staley, an early member of AIDS Coalition to Unleash Power (ACT-UP), wryly noted that “On January 25, 1991, this is how the New York Times reported that 100,000 people died from AIDS. They didn’t bother writing their own story. They ran an Associated Press story instead. On page 18. Below the fold. No pictures. No names.”

When I read the physical list of names of what amounted to just a small percentage of those lost so far, it felt overwhelming, incredibly sad, and eerily familiar. Any LGBTQ person in the United States, particularly those of a certain age, was transported back in time to another physical archive of loss and mourning created in response to government inaction and indifference — the Names Project AIDS Memorial Quilt. The AIDS quilt was conceived in 1985 and first displayed in 1987 in the National Mall in Washington, DC. 1987 was six years into the epidemic but the first time that President Reagan actively addressed HIV/AIDS. Up until then, the press and the federal administration didn’t seem to care about AIDS; they laughed and joked about it at the press conference when the journalist Lester Kinsolving asked the first question about HIV/AIDS. In the infamous episode, Kinsolving asked Deputy Press Secretary Larry Speakes whether or not Reagan was aware of AIDS, known then colloquially as “gay plague,” Speakes laughed at him, said he didn’t have it and asked if Kinsolving did. While Speakes and the press corps laughed, Kinsolving asked, “Does the President . . . in other words, the White House looks on this as a great joke?”

Hidden in the press secretary and the press corps’ laughter was disdain, fear of contagion, and fear of being othered. As Susan Sontag wrote in Illness as Metaphor, “Any disease that is treated as a mystery and acutely enough feared will be felt to be morally, if not literally, contagious.”

In the early days of AIDS, stigma and fear surrounded not only those dying from the disease but the bodies of those who died. Unclaimed bodies in New York City were sent to potter’s field in Hart Island, an island off the Bronx. Hundreds of AIDS patients were buried there during the 1980s and 1990s, particularly those who were estranged from their families of origin and without funds for a proper burial. Some funeral homes refused to handle AIDS corpses, because of homophobia, transphobia, and ignorance of post-death disease transmission. It is difficult to determine the number of the deceased on Hart Island because of the stigma that surrounded the burial practices there — nameless mass graves make people reckon with how people deserve to be memorialized and remembered. In “Dead of AIDS and Forgotten in Potter’s Field,” a 2018 New York Times article, Corey Kilgannon said city officials refused to speak with him and insisted that no data was available on AIDS burials. However,

piecing together an estimate is possible by surveying the many hospitals that treated AIDS patients during the epidemic and sent bodies to potter’s field. By that accounting, the number of AIDS burials on Hart Island could reach into the thousands, making it perhaps the single largest burial ground in the country for people with AIDS.

The government, the medical establishment, and many of the victims’ families of origin stigmatized AIDS victims both pre- and post-death, blocking and shaming their mourning rituals. The Names Quilt, however, created a different space of mourning, celebration, and activism, by demanding that the viewer recognize that these humans were here and that their lives mattered.

Each panel is 3 feet by 6 feet, the size of a typical grave. The quilt now has approximately 48,000 panels and is physically too large to be displayed in the Mall in Washington. In 2012, a joint project between Microsoft, the University of Iowa, University of Southern California and the Names Quilt Foundation digitized the AIDS quilt. In an article in Open Culture detailing this new form of the quilt, Kate Rix writes, “Like any good archive — and the quilt is an archive of life and loss — the AIDS Memorial Quilt serves as a historical repository, a storehouse of sentimental information for scores of people. But beyond that the quilt is a piece of political folk art.” How we memorialize people has not just personal but political significance.

•

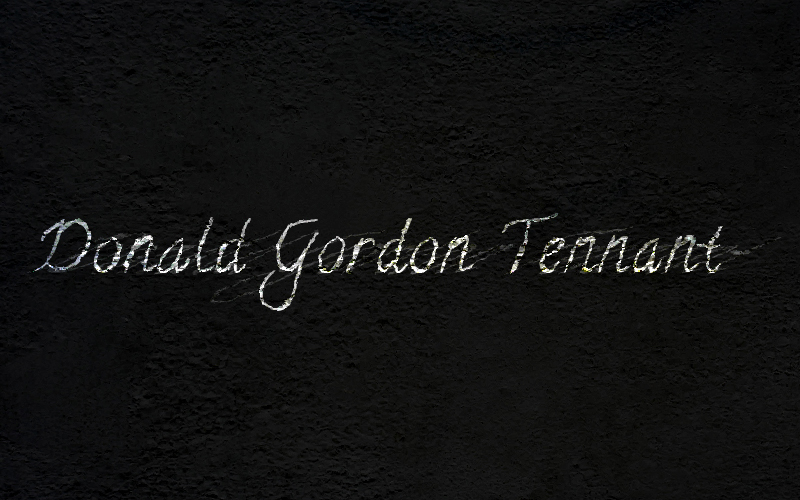

Donald Gordon Tennant, 35, Loving father, son, and brother. Had the sweetest smile.

On June 1, 2020, a week after the Memorial Day New York Times Covid-19 archive, I revisited one of my own archives of loss, on the 36th anniversary of my dad’s death from suicide. My daughters turned eight a few days later — the same age I was when he died. Eight is such an interesting age because eight-year-olds are so big and so small at the same time. Articulate and wildly intelligent, my girls still have so many visceral and absolute needs. At this age, I didn’t know that my father had taken his own life — that he was John Doe 62, body found in the waters of the San Francisco Bay. My mom knew that I shouldn’t have to deal with that reality for many years. All I knew at that age was that he was gone and that I needed him.

The days between June 1st and the funeral were a bit of a blur for me. Things I remember: sleeping on the floor for one night in my mom and stepmom’s room; going with my mom the next day to buy a blue photo album (his favorite color) and starting to put the photos in; having our family friend, a Presbyterian minister and LGBT activist, perform his memorial. Going with my dad’s ex-girlfriend and her son after the funeral reception to see Star Trek 3: The Search for Spock. Perhaps this is the reason I don’t like the Star Trek movies. Writing in my second-grade journal after I returned to school, “I was gone for a few days,” because I couldn’t write anything else.

Burial was later, a different day than the memorial, and it was in Colma, a town near the San Francisco airport where there are literally more dead people than living. There are many cemeteries there and one contains members of both sides of my family. My mom’s family is in the mausoleum and my dad’s side are in graves — my Uncle John, my dad, and later my grandpa and grandma. We didn’t have to go to the burial, my mom didn’t force us, and when she asked I said that I didn’t want to and she didn’t push it. About a year later, I was at my grandparents’ house and they said that we were going to visit his grave and I just couldn’t. I was a very good, yet very sensitive child, always wanting to go along with things so that people would still love me and not leave me. But I just couldn’t do this and had a meltdown that didn’t abate until they agreed not to go. I couldn’t face the absolute fact that his body was there in the ground in Colma and that I would never see and be held by that body again. If I didn’t go to the cemetery, there was a chance that he was just gone for a while. Over the years, I realized that I carry him in my own memories, in my family’s stories, in the physical mementos, and photos that remain. When my grandpa died 15 years later, we went to his burial and I was able to go a few stones over and really look at the one with my father’s name. I could touch it with my fingers and say, “Hi Daddy, I miss you and I love you and I wish I knew you.” I’ve only gone back a few times for other family funerals, but I do this every time as a new kind of ritual. That was also around the time when I could tell people outside a very close circle that my father had taken his own life. I let go of the “hiking accident” story that my mom had used to protect us. I carried the way that he died as a shameful secret for so long as if his suicide would make him look selfish and us unwanted and unloved. But with the help of therapy, talking with loved ones about his mental illness, and the various rituals I have to remember and celebrate him, I can be honest with myself and others. I wasn’t able to handle the mourning rituals when I was a child and a teenager — at that time, his loss was too recent and society was still so judgmental of mental illness and suicide. But talk therapy — itself a ritual — and the creation of private and family moments have helped me heal, remember the beautiful man he was, and move forward.

Even in 2020, there is still a persistent assumption that it is better to have a physical ailment than a mental illness. Moral judgment still surrounds mental illness and survivors of suicide. Writing about cancer in Illness as Metaphor, Susan Sontag said, “But no one thinks of concealing the truth from a cardiac patient: there is nothing shameful about a heart attack. Cancer patients are lied to, not just because the disease is (or is thought to be) a death sentence, but because it is felt to be obscene — in the original meaning of that word: ill-omened, abominable, repugnant to the senses. Cardiac disease implies a weakness, trouble, failure that is mechanical; there is no disgrace, nothing taboo that once surrounded people afflicted with TB and still surrounds those who have cancer.” This quote is comforting to me because in 2020, it seems almost comical to think that cancer would be treated as shameful. This gives me hope that with more advocacy, more treatments, and more people sharing their own experiences as a person with a mental illness or as a family member, in the not-so-distant future society’s views about this will change.

•

Silences enter the process of historical production at four crucial moments: the moment of fact creation (the making of sources); the moment of fact assembly (the making of archives); the moment of fact retrieval (the making of narratives); and the moment of retrospective significance (the making of history in the final instance).

Michel-Rolf Trouillot, Silencing the Past

The inability to properly mourn because of contagion fears, shame, or moral judgment of illness inhibits the necessary work of personal and collective mourning. Silences get embedded in the sources, the archives, the narratives, and the history and affect not only the direct mourners but also how future generations reckon with these losses. How do we construct archives of loss (the New York Times memorial, the AIDS quilt, the photo album) and what do those archives mean, especially in the absence of conventional rituals of mourning? My own process of learning what and how to mourn has been a patchwork one, breaking through silences, and giving myself space, permission, and compassion to do so. We as individuals and as a culture have a right to mourning, to ritual, to togetherness, to celebration both in grief and in joy. It helps us move forward and grow stronger, and just as Jose Muñoz reminded us about melancholia in Disidentifications, these rituals of loss and remembering are “a mechanism that helps us (re)construct identity and take our dead with us to the various battles we must wage in their names — and in our names.”