Norman Rockwell must have inspired the designers of the Massachusetts VA (Veterans Affairs) Hospital I worked at during grad school, as the campus they created reproduced many of the trappings of the tidy American suburb. Clusters of small, house-like buildings sat scattered amongst acres of once lush lawn. A network of concrete footpaths connected the clusters, cutting a series of tree-lined curves that would be carpeted in a leafy shag by fall. But there were no rosy-faced kids pedaling bikes and filling the air with laugher, no bright-eyed dogs chasing drool-drenched balls. Instead, the vibe was unmistakably institutional, a community populated largely by men, most fundamentally broken and at odds with the specific kind of belonging embodied in the quaint neighborhoods the hospital labored so hard to replicate.

I was pursuing a master’s degree in psychology when I found myself working at the VA, assisting one of my professors while serving as project coordinator for a large study funded by the National Institute of Mental Health. The professor was a favorite of mine. He taught me plenty, but we also laughed a lot, often over the musings of Saturday Night Live’s Stuart Smalley, whose line because I’m good enough, I’m smart enough, and doggone it, people like me never failed to crack us up.

Smalley’s book might have been the only element of contemporary pop culture in the small basement office the professor and I shared, furnished as it was with relics from decades past. My hulking metal desk bore traces of the art deco designs that inspired it, with bombshell curves and strong-man drawers. The black resin telephone with its big glowing buttons hailed from the mid-century, while the Reagan era gave us the tiny clock radio tuned permanently to NPR. I did have a gigantic, then state-of-the-art computer equipped with a dial-up modem, which at the time seemed like some kind of miracle, but I was hemmed in on all sides by aging data sets printed on reams of dot-matrix paper that had to be moved up off the floor with every approaching storm lest the basement flood and destroy them. This was how federally funded research got done at our site in the early 1990s.

I have never felt more Californian than when I worked at the VA. I was in my early 20s at the time, some might say a full-fledged adult, but I found myself longing for my childhood however imperfect and the freethinking artists, spiritually inclined surfers, and nurturing family who populated it. The demographic at the VA, by contrast, skewed more reclusive and sedated, nervy and serious. The inter-departmental mail carrier who handed me letters every day did so without making eye contact or uttering a word, while the librarian — another participant in the hospital’s occupational therapy program — asked too many questions too loudly, fueled as he was by barely restrained mania. A shaky cluster of chain-smokers greeted me on the steps of the main building, and once inside I was surrounded by straight-faced doctors and administrators clad in status-minded scrubs and suits. The gravity of the problems, the permanence of the damage, and the lingering smell of disinfectant — all of it conspired to make the VA’s idyllic environment more of a threat than a solace. I clung to my billowing palazzo pants and woven tote bags as reminders of California’s optimism and glamor, my brightly printed scarves flapping in the wind as I steered the impractical convertible I couldn’t afford up the hospital drive.

Our study focused on first-degree relatives of diagnosed schizophrenics. We compared interviews with them against those from a control group to determine if the relatives were more or less likely to have what is known as schizotypal personality disorder. This could help establish a genetic link between the two conditions. On its website, the Mayo Clinic says that people with schizotypal personality disorder are often described as “odd or eccentric.” Eccentricity was considered a compliment where I came from — the people back home generally more interested in standing out than fitting in — but I started to question this assessment at the VA. To be fair, many other criteria must be met to be diagnosed as schizotypal, but the one that confounded me most was magical thinking, a way of interpreting harmless, inconsequential events as having special significance or power. Our interview included questions like “when listening to the radio, have you ever heard any messages just for you?” or “when driving, do road signs feel like they were put out just so you could see them?” It seemed like what we were really asking was “do you see life as rich in significance or full of random coincidence?” The former, please, and many times over. How else was meaning to be made and art to be created?

Our team of four interviewers included two people from California and two from Massachusetts. In order to generate reliable data, we had to agree as a group on which beliefs and behaviors were normal and which were pathological, ranking them on a scale of one to six, where one is completely normal, six completely pathological, and four the point at which things start to spin away from sane. To calibrate our assessments, we conducted the first round of interviews together, then compared notes to see where our views aligned and where they diverged.

One of our earliest interviews was with a woman who was especially enthusiastic about magical thinking.

“Yes!” she exclaimed. “The world is full of signs that guide me!”

Later, as we sat parsing the data, the professor looked up from the table, leaned back in his chair with his hands folded behind his head, gave a wry little smile, and said, “So how did you guys rank that answer?”

“I gave it a two,” I said.

“Are you kidding me?” one of my east coast colleagues railed. “That was a four at least. I marked it a five.”

The professor just chuckled, the influence of California’s liberal-minded approach by then clear to us all. What was also clear: While some of us would have to be less rigid in their thinking, I would have to be more conservative in mine.

That psychiatrists considered magical thinking a clinical symptom in the first place came as a shock. To me, it was just the everyday behavior of the average participant in the annual psychic fair, a harmless affliction rather than a problem that needed fixing, maybe even something worth cultivating depending upon the relative creativity of one’s occupation. Magical thinking helped children celebrate lost teeth along their journey to adulthood, made the experience of a butterfly landing on the lip of a teacup more than just a happy accident, was the cornerstone of much ritualistic and religious belief. I had grown up with plenty of it, from my mother’s long-burning candles and ever-changing altars to my grandmother’s staunch belief in the healing power of positive thought to the way I was encouraged to seek the divine in the spiritual signs of the natural world. These things were common currency in the California of my youth and to my mind made the world merrier, a feeling I recognized as being in extremely short supply at the VA. My family’s familiar way was far too warm to give up on, but the authority of the professor I looked up to was tough to contradict. The discrepancies made me nervous.

“So why is magical thinking pathologized,” I asked the professor one morning, adopting the nonchalant tone of the intellectually curious as a way to disguise my personal concern. “It seems harmless.”

“Because it’s not real,” he said, as if it could not be more obvious.

This was a man who had been at Woodstock and who presumably had at least a few remnants of counterculture tucked away somewhere, but in the cool precision of his academic persona, magical thinking lay on the spectrum of madness. What would he see in my mother’s altars but molten wax and a mishmash of pictures and found objects? And what would he make of the silver bracelet I had worn that day specifically to give me strength? I doubt the professor considered me anywhere close to mad, but his easy answer to my question made my stomach drop. Admittedly, real psychosis, the kind where all grip on reality is lost, was both a huge ways down the road and something no one in my family had ever suffered, but to be on that road at all seemed to be a perilous venture. I took a deep breath to steady myself.

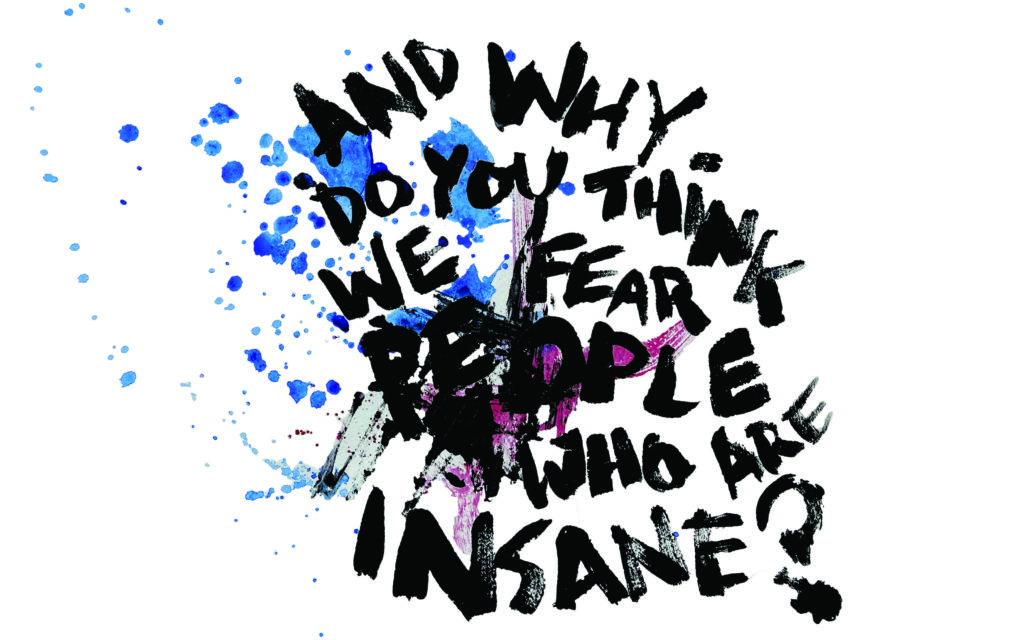

“And why do you think we fear people who are insane?” I continued tentatively.

“Because they lack a consistent personality and thus make it impossible for us to really connect with them,” he said plainly as he continued to type.

“That’s sad,” I replied.

I hung up my jacket with jittery hands, the silver strands of my bracelet slipping down my arm, and taking my sense of self down with them. I thought about the librarian and mail carrier again. I didn’t fear them because they lacked a consistent personality, but I did fear the way they seemed to struggle to connect and the scarce compassion they received from the culture at large. And there was a way in which the hospital’s stylized straightness magnified their accidental otherness, pushed them away rather than gathering them up even though they seemed to me like those most in need of real care. I didn’t want anything to do with either side of this equation. Though I couldn’t articulate all this back then I did feel it, my whole body by now atremble.

“But not all psychotics are unhappy,” a clinical psychologist who worked on our study countered as she came through our door, having heard our conversation from down the hall and seemingly read my thoughts. “I was walking with a patient the other day when he started laughing, telling me that the trees around us were cracking all kinds of great jokes.”

Whether she meant to defend psychotics or reassure me I don’t know, but either way, I was left unsettled. As the minutes ticked by the demands of work grew more pressing and I managed to pause my thoughts long enough to get on with it, but I sensed I wouldn’t be able to muster that kind of strength much longer.

Winter arrived abruptly that year in New England. The trees went dormant and we were bombarded with blizzard after blizzard, the weather becoming the main news on NPR. I left work early one afternoon with the hopes of missing the latest storm bearing down upon us but found myself stuck in traffic instead, limping along the highway until we all came to a complete stop, at which point I got out of the car, stumbled about in the powdery drifts stacked up along the roadside, and tried to clear my window with an ice scraper in the evening dark. I made it home after hours of dodgy travel, and by the time I finally went to bed the next day’s work had already been canceled, stores shuttered and highways closed. The following morning I woke to my first ever snow day, something California girls fantasize about on warm February afternoons in the classroom but which I found a little more unnerving at home alone in my tiny Massachusetts apartment.

On that particular day, everything was very hushed in the way I came to recognize about major northeastern storms, the air thick, somber, and padded with the weight of snow. I was sitting at the flimsy table by the window that doubled as dining table and desk, reading through a paper on personality disorders and recognizing pieces of myself in yet another helter-skelter diagnosis, when I became so filled with self-doubt as to be completely consumed by it. Swirls of white whipped at the window, the paper in my hands shaking in time as the word disorder ran laps around my brain. I watched the world grow increasingly unreal as my heart pounded wildly and my body floated weightless and dizzy. I pressed my face closer to the glass but my clammy breath only clouded the view. I was sobbing, my respiration ragged and my chest tight. Time seemed to drip by, each second vivid and loaded and long, my body hit with a surge of heat that retreated as swiftly as it struck, leaving me to shiver in the cold. I was floundering yet motionless, the too-familiar chair at that moment like the helm of a boat caught out in the Atlantic, heading too slow up the face of an icy wave about to break down and rip my vessel in two. The feeling was one of sheer terror, the sensations so all-encompassing, so utterly convincing, and so completely out of sync with the unremarkable apartment. I considered calling 911 but couldn’t imagine how I’d explain my particular emergency. This, I thought, must be what it’s like to go crazy. In fact, I’m going crazy, right here, right now, and I’m so afraid of myself, so horrified by my own mind and body, cannot trust myself now and clearly never will again. These thoughts buried me down, down into the deepest recesses where all light was obscured.

And then from somewhere inside me there came out of nowhere a tiny impulse. I moved at last dashing to the closet and wrenching open the door so hard it banged against the plaster wall, and fished out the strangest of life vests: a table-top ironing board with three-inch legs I had gotten when I first left home. I found my flimsy Black & Decker iron, plugged it in, sat down on the floor, and proceeded to press almost everything I owned. Later I stood for a long time in a scalding hot shower, feeling my muscles slowly release. And then, days after that, I found myself sitting across from a psychiatrist of my own, having been referred there by the university health service.

“You had a massive panic attack and that’s something I can help with,” the doctor assured me as she scribbled on her prescription pad. And then she stopped and looked up at me. “But really I think you’re just extremely lonely.”

I could only nod in approval, my lips trembling while tears pooled near my nose.

Although today’s psychiatrists might prescribe an SSRI like Paxil to treat panic, those drugs were used mainly for depression when I was seeking treatment and so I was given Klonopin instead, a benzodiazepine related to Valium.

The first time I picked up my prescription, the pharmacist took me aside and gently explained the drug’s danger of addiction and other possible side effects, taking care to show me each of the many warning labels covering the small brown bottle, speaking slowly and softly as if I were a frightened animal about to bolt into the woods. CAUSES DROWSINESS. TAKE ONLY AS PRESCRIBED. DO NOT OPERATE HEAVY MACHINERY. MAY INCREASE THE EFFECT OF ALCOHOL. My already hyperactive fight-or-flight response went into overdrive, and all I could see were a dozen red stickers screaming DANGER DANGER RUN FOR YOUR LIFE.

I spent the remainder of the day studying the microscopic print on the medication information sheet, unfolding and refolding the tissue-thin paper until all the creases went slack. I worried about the glass of wine I enjoyed in the evenings, wondered if my car counted as heavy machinery, and most of all dreaded the moment I’d actually have to take the pill and cede my rickety self-control to its slippery pharmaceutical effects. Once I did, I fell quickly into a deep, dreamless sleep, as if someone had dragged a heavy blanket up the length of my body, its weight slowly numbing my toes, my legs, my torso, until my head powered down and I slept. I woke late the next morning, but it didn’t take long for the anxiety to wake up too, snaking its way through my body with every bite of breakfast. I had more panic attacks, some more intense and others less so, but somehow I lumbered through the days, a magazine clipping I had taped over my bed becoming a kind of talisman. It featured a languid figure rendered in watercolor walking through a warm haze beside a quote from Albert Camus: In the midst of winter, I found there was, within me, an invincible summer.

Back at work, we continued the process of calibrating our rankings by collectively interviewing patients who had been diagnosed with full-blown schizophrenia. These patients had lots of magical material to draw upon when answering our questions, and that gave us lots of chances to tease out the difference between pathological and not.

One day I found myself interviewing a man in his mid-30s. He was wearing clean clothes and answered most of the establishing questions — what’s your name, where do you live—coherently. It was going well, his medication clearly working. And then I started to question him about magical thinking.

“Have you ever received messages specifically for you from sources outside your body?” He just rolled his eyes at me in exasperation like I should know better.

“Of course I have. They communicate with me using the cybernetic structure they implanted in my brain,” he said, reaching around himself to point at the base of his skull. “They tell me I’m a bad person and threaten me, and I can’t trust anybody. Worst of all, I can’t ever get rid of the structure or turn it off.”

I had expected him to answer yes but was blindsided by the details, which I recognized instantaneously as something far different from my mother’s altars and grandmother’s prescription for positive thought. My eyes were glued to his face, my pen hovering above the page, my feelings equal parts fellowship and fear.

Then he leaned toward me and whispered, “You wouldn’t want a cybernetic structure in your head.”

Here, I thought, was the most unreliable of narrators, and yet never had something more true been spoken. I absolutely did not want a cybernetic structure in my head. Nor did I want the milder schizotypy, or the panic I’d recently acquired, or any disorder or diagnosis. Had someone asked me just then if I had ever received messages specifically for me from sources outside my body, I would have answered with an emphatic yes.

“Is it OK if I ask the next question now?’ I finally said. I looked over and saw the professor nod his head at me in approval.

It felt cruel to move on, another abandonment in this man’s world. But I was just an interviewer, after all, a student still, far from home and not particularly reliable myself, and despite the profundity of his statement, we had gotten what we came for: an undeniable six, as assessed by each and every one of us.

I graduated in June with a master’s degree but by then I had given up on psychology as a career, knowing it would be, instead, my personal vocation. I sold or gave away almost everything from that pivotal apartment, glad to be rid of it, then packed up what was left and made my way home. I found California as golden as ever upon my return but I shined less brightly than before, my plate tectonics as shifty now as those upon which the state was built, and trailing as I was the weighty residue of a winter in Massachusetts from which I have never quite dug out. •