The ultimate American Christmas novel for an age needing it the most.

As we descend lower into what I think of as the inveigle age — and we must be down around the catacombs by now — I increasingly esteem qualities that I used to take for granted, even if they were never easy to come by. Consistency for one, candor sans artifice, for another; the courage to be one’s self on account of the richness inherent in that endeavor, rather than to curry favor. Each of these qualities falls under the auspices of self-determination, which has become a throwback virtue. I think on these themes throughout the year, but more so at Christmas, a time that for me remains one of remaking who we are — if we wish to.

Arkham House, a press specializing in weird fiction, encapsulates this ethos, and with one Christmas-related book in particular, which we shall come to.

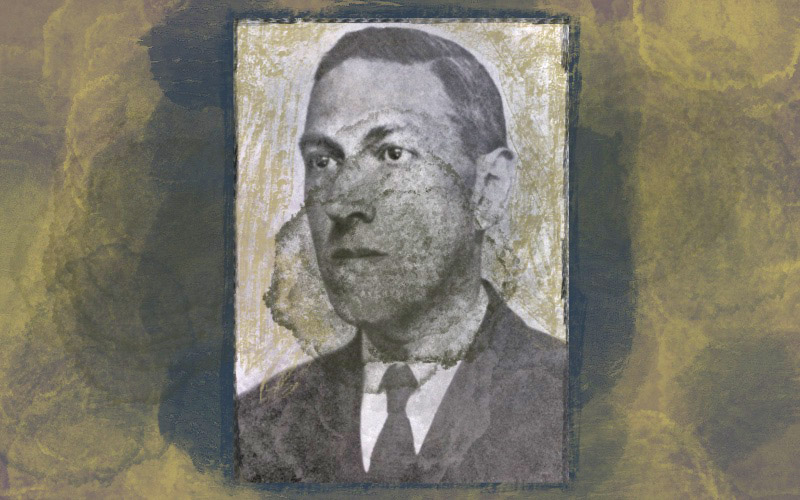

Founded in 1939, Arkham House, in its eldritch heyday, specialized in some of the darkest pockets of American fiction. Based in Sauk City, Wisconsin, the press was established up by two friends of H.P Lovecraft — August Derleth and Donald Wandrei — with the aim of providing a Lovecraftian stable for that epoch-rattling — and epoch-traversing — manner of strange fiction, while safeguarding some might say spearheading Lovecraft’s own legacy. Derleth wrote 100 books in his lifetime, and you wouldn’t want to even try to guess how many he must have read. The man was the reading experience in walking form. Wandrei was a writer of weird fiction, which at the time meant that you likely had a beef with the world for overlooking the Lovecraft, who inspired great loyalty in his acolytes. When publishers had no interest in the Lovecraftian wares that Wandrei and Derleth were hawking, they set up shop in business, and Arkham was born.

Arkham titles were issued in low print runs of random numbers which also conjured a spectral feel at the book-keeping/counting level — blink, and a title was like to be out-of-print, as if it had barely existed in the first place. Spooky math. Lovecraft had died two years prior, but conceivably no other American writer has spawned so many acolytes, believers, and expanders of a fictional universe functioning like psychical amanuenses.

Some of that has to do with Lovecraft being a man who would correspond with just about anyone. You could say that Arkham was built from the correspondence that men like Derleth and Wandrei had with Lovecraft. They shared ideas with a passion — ideas that the reading world at large didn’t normally dabble in.

When Lovecraft’s name comes up now, it’s usually in connection with the putridity of his thoughts on race, which were given ample airing in those letters. At the same time, the better parts of his imagination benefited from far less ugly brand of tearaway spirit. Lovecraft’s horror stood on no ceremony, and it wasn’t indebted to the horror mores that he’d grown up with, and on which he wrote about so well in a long essay on the best of the best of terror and weird fiction. For Lovecraft — and so, too, many of the best writers of Arkham — one must depart from traditional planes, those that are congruous with everyday experience, and serve up a penumbra world instead. This involves formal risk, within the construction of these narratives, plus a willingness to inhabit terror zones such that stories might be imbued with something of the same stuff. You’re kind of like a Marine in the unmapped territory of the human psyche’s shadow realm. Hence, I think, a degree of flocking together, black-plumed birds of the night.

Arkham restored to print classics that might not have become classics without Arkham assistance, from the likes of Algernon Blackwood, William Hope Hodgson, Sheridan Le Fanu, Derleth himself was a fascinating writer, who created the ultimate Sherlock Holmes pastiche with his Solar Pons detective character, while being a veritable one-man-library, shelves buckling under his prodigious output. He composed stories in Lovecraft’s Cthulhu Mythos cycle, innumerable works of what was then termed — in another wonderful coinage — Cosmic Horror, plus biography, locked room mysteries, science fiction, poetry, historical fiction, naturalism, and sheaths of letters.

Arkham writers, as a trend, went out and got things, debated, argued, created, all but sweated strange and macabre prose, lived well weirdly, we might say, if by “lived” we mean composed, which was essentially life to an Arkhamian. The books from that vintage run, as you might imagine, command huge dollar figures among collectors. They are beautiful living artifacts, too, solid—no other press’s books feel so much to me like formidable clay bricks you can transport in a pocket — and with evocative covers art-directed, it would seem, for the purpose of tingling brain crannies where fear and delight find fruitful union.

But what if one were to suggest that what might be the greatest work of Christmas fiction produced in this country stemmed from this small press, with its tiny print runs? Would that be grounds for incredulity? Because we would have to assume that this would not be a happy Christmas tale of corrective spirits, or a corpulent elf descending down a chimney with toy train set rarin’ to go. And yet, we do have a tale of the origins of Santa Claus, with Seabury Quinn’s Roads, a certifiable Arkham doozy, America’s literary answer to Dickens tale of Scrooge, via a tale of a centurion.

We might say that Quinn was a Christmas person from birth, until death. He was born — we are not sure the date — in December 1889, and died on Christmas Eve, 1969. Upon serving in WWI, he became a government lawyer who also wrote for the pulps. As with Derleth, he went the detective route, creating the sleuthing Jules de Grandin — the surname coming from Quinn’s own middle name — and penned horror work suggestive of Maupassant. These early efforts immediately following from the Great War were vertiginous, disorienting, what might be termed, several decades later, the reading version of a bad trip, man. There was no shortage of Quinn material, as he composed more than 500 short stories while launching trade magazines and disseminating his legal advice.

We have to keep in mind that for quite a while, weird fiction, as well as science fiction, was viewed as the remit of the plebian, the knuckle dragger, the sort of adult who still rode a bike with baseball cards stuck in the spokes.

The irony is that the best of this material, from this era, numbers among the most imaginative literature ever produced in this country. Arkham House was tough to beat for straight-up invention. Reading the best of Quinn and the Arkham writers, you have the feeling that anyone could do so-called social realism — yawn — but the siring of worlds, which in effect is what this form of writing was—not that it was limited to a single or prevailing form — was where the rubber of genius met the sweet, sun-glazed asphalt of, well, the road. Which brings us to Roads, Quinn’s first full-scale book.

It was also Arkham House’s first illustrated title, Virgil Finlay’s pen and ink drawings reminiscent, with their fine-grain filigree and cross-hatching, of the sketches Van Gogh would make in the margins of his letters to brother Theo. Roads had already appeared in Weird Tales Magazine way back in January 1938, albeit in rougher form before Quinn turned to some refining revisions. The decade-long gap was such, and magazines disposable enough — there were, of course, no digital records — that Quinn’s origin tale for Santa Claus would have been new to any prospective reader at the tail end of the 1940s.

Weird fiction, as the Arkham masters like Quinn delivered it, didn’t need to feature ghosts or the otherworldly. The invention quota had to be high, but perhaps the key tenant is that there would be no disclaimers that you needed to accept a certain set of rules divorced from the reality we know, as these disclaimers undercut potency.

The prose tends to be very plummy. Plummy trending to purple. And yet, it’s seldom pretentious. You might call it spectral, but entirely of our world. In a weird way.

Roads (printed in an initial run of 2,137 copies) begins as though it is going to be a sword-and-sandal epic, a tale of gladiatorial might set in and around Bethlehem.

Claudius is what the narrative terms a Northman, originating from land by the sea, perhaps Scandinavia. He is something of a freelance soldier, who also fights in the circus to make some extra money.

“He was brawny and wide-shouldered, his hair was braided in two long fair plaits that fell on either side of his face beneath his iron skullcap. Like his hair his beard was golden as the ripening wheat, and hung well down upon his breastplate,” we are told.

Quinn soaks up this language and soaks us in it. He relishes the deployment of his terms, his loan words, his invented words; this is quite the argot salad, but the terms become familiar, become our terms, like a weird fiction version of the language used by Burgess in A Clockwork Orange. The story starts with Claudius on the road between gigs. He is, as you might expect, on the road a lot. This is the time of Herod, and Herod, threatened by the coming of the Christ child, has issued a decree to have boy children slaughtered.

Quinn instills this idea that Claudius here is a man of self-determination, who is going to act based upon his internal dialogues, informed though they may be by the valuable counsel of others. To put it another way, this soldier, this walker of roads, is no follower. He is inchoate, but we realize this will be a story of how one man — a person — comes together.

But first, he must come together with a wailing woman whose boy has been killed by Herod’s men, which takes some effort for Claudius to process, accustomed as he is to following orders. The woman has no money for a burial, so he gives her some coins, sets out again on his road, until he hears a different cry — a scream for help this time. Soldiers have set upon a family comprising a man around the age of fifty, a girl whom Claudius estimates to be fifteen, and the swaddled child of this girl. The soldiers — Herod’s men — are not only dispatched, but they are also dealt with by “Claus the Smiter” with the additional fury he acquired from having seen what was done to the babe of the woman he recently left.

“And on the bodies of his fallen foes, he kicked the gray road dust, and spat on them and named them churls and nidderings and unfit wearers of the mail of men of war.” It’s a bit Conan the Barbarian — but it’s pretty awesome.

This is the manner of dichotomy we’ll see Claus grapple with within the novel. His past and what he knows takes him one way; his growth as an individual, another. What will facilitate the latter is a decision of self-actualization. To buck trends. Expectations. To discover what he can know, rather than revisit the patterns he’s known for so long.

His deed complete, he prepares to move on, but the swaddled child beckons him. Nobody hears anything. Claus hears nothing, yet he approaches the infant. There will be a number of these exchanges in the book, and their power is remarkable.

Quinn knew what he was doing. He enfolds a dialogue in silence, a sort of mental communion, between babe and man — and another layer of silence as well, with us, the reader, as this is the nature of reading. We are listening in on someone listening in, as if Claus, too, was reading, with character and reader instead of hearing. A trinity is established: Claus, child, reader. The moment feels holy, the witnessing of a compact. Think of it as a form of secular holiness, because Claus is certainly no man of the cloth, he’s no pro-mystic, but he also understands purpose.

“’Claus, Claus,’ the softly modulated voice proclaimed, ‘because thou hast done this for me and risked thy life and freedom for a little child, I say that never shalt thou taste of death until thy work for me is finished.”

Note the last word — it’s a play on Christ’s final words, upon the cross, “It is finished,” which we will encounter later. Time has been thwacked here, it’s not in the order we associate with time. The infant is wise, the infant knows of its death as an adult, the infant understands how change may occur in a human and that it is the individual human, ultimately, no matter the prompt, that is the agent of change.

Everything is before its time, and also of its time — which is to say, it’s not too late. Not too late for Claus, who is no maker of excuses. A time will come when Claus outlives the old gods, who will be forgotten — the Christ infant is a confident speaker — and live “so long as gleeful children praise thy name at the season of the winter solstice.” Shorter days, longer life.

Claus ends up in the employ of Pontius Pilate, an ineffective, hen-pecked bureaucrat with his own set of problems and rivals with which to deal. Christ is nailed to the cross and it is Claudius who delivers him his mortal blow when he deems that he can no longer allow the suffering to continue. His spear pierces the heart, but once more, a voice speaks, one which no one can hear, save Claus within the bones of his skull. The same tone, the same cadence. “Thy work is not yet started, Claus,” says the voice. And then occurs one of the most remarkable moments I know of in literature in which the sacred and the secular are fused.

“The soldiers of the guard and crowd of hang-jawed watchers at the execution ground were thunderstruck to see the Procurator’s chief centurion draw himself up and salute the body on the gallows as though it were a tribune, or the Governor himself.”

Again, to the road. Hastening “through the Street of David” to report back to Pilate, the world starts going way, way wrong, like it often does in a Charley Patton blues. There is an earthquake, Claus ends up saving a prostitute.

Deed completed, and having ascertained the woman’s current occupation, he wants nothing to do with her, until, again, the voice sounds in his head. You understand where this is heading. This is the future Ms. Claus, and together with Claudius she will journey many roads, stand by his side in many battles, narrowly avert execution with him by returning to the road under cover of darkness after having performed a small gesture of kindness — the handing out of toys, in one instance — deemed to violate the local religious decree.

Time, meanwhile, travels another road. “Emperors came and went.” Both man and woman live on. They certainly live by their own code. Despite what he has witnessed, Claus does not stop soldiering. He views — correctly — his conduct even as a solider as autonomous, the fruit of his purpose. He is a taker of responsibility. This inspires some, terrifies others. His progress never ceases, and as such the road — the journeying — is a metaphor. Constant movement is equated with perpetual growth. The destination is the payoff, but the destination is temporary; the next destination is central. And so on.

Claus is determinism unto himself, that is, self-determinism. Traveling in the north, along Baltic shores, the duo encounters the aelf people — elf, that is — down on their luck, slandered throughout the land as agents of evil, imps as disembowels of decency, who nonetheless wish only to help humankind.

One might remember the spirits gathered around the ghost of Jacob Marley outside of Scrooge’s window, unable to help the poor and thus ululating in the wind, their chains playing a keening song of impotence and lament. These aelf people have a similar issue, which Claus and his wife solve by offering them a job, for these aelves are most useful. They have magic reindeer, which can fly, and they are master craftsmen, and fast at it, too.

Following the first of the worldwide deliveries of Christmas presents, everyone “drank and drank again to childhood’s happiness,” and our origin tale is complete. As an Arkham novel, Roads is both atypical — you usually have more of a horror component — but entirely representative of what I view as the undergirding of the press, its mission statement: to plumb the protean imagination that often belongs solely to the child, which the adult forsakes in the years after childhood is laid to rest.

It is childhood we return to in Roads, the Arkham title of the purest heart because that is the flux time, but it need not be the only flux time. The adult often does not, but the adult might grow, adapt, as much in later years as the child does in his or her first few. Culpability is nearly torrential in this story, a riposte to shirking, puling. And yet it remains an exegesis of faith. But even in the moments that flirt with religiosity, the faith comes from within, from the individual. That he turns out to be Santa Claus — or a metaphor for him — puts that figure squarely in our imagination, where the best parts of us, like this, the best fiction, can travel its own road and find a way into the world. •