Watching the films of Michael Powell and Emeric Pressburger — the movie production team who dubbed themselves the Archers — it’s likely the viewer will find themselves suffused with a feeling they don’t expect to experience from watching a movie. We come to cinema to escape, relate, be entertained, learn what may be beyond our ken up until that moment, or better understand the world of our remit. What we generally do is take. Which is fine — that’s the nature of the transaction. But the films of Powell and Pressburger stir a different emotion — they cause us to wish to give thanks for what we’ve experienced, and act so that others may be similarly inspired by us, as Powell and Pressburger touch the lives of their audience.

When Disney is mentioned now, it’s often thought of as “big media,” the place that shapes and bankrolls the likes of the Star Wars universe. But Disney used to be a magic factory, a studio that took you away and, in doing so, imparted some knowledge about where you’d been and would be returning to come the close of Fantasia or Snow White. And yet, for all of that Disney wonder, I would suggest that no filmmakers have ever purveyed magic to the degree of Powell and Pressburger. Theirs is a bounty cinema, as I think of it, a vast harvest of transcendent human experience, and this duo — an Englishman and a German — made perhaps cinema’s purest work of the act of giving thanks, with us then thanking them in return, for their celluloid proof — and assertion — of the existence of daily miracles.

One will be entranced by any Powell and Pressburger film, for entrancement is the nature of their art. Their ardent admirers are devoted with admirable passion to the film that stirs them the most. But whether it is A Matter of Life and Death, I Know Where I’m Going!, Black Narcissus, The Life and Death of Colonel Blimp, what the Archers do is surprise you. In surprising you, they remind you — or maybe help make you aware for the first time, or the first time since you were a child — that there are actual surprises in this often rote-feeling, paint-by-numbers world of ours. I don’t mean the surprise of death, or the shocking phone call from the doctor for the test that was supposed to be a formality. I am talking about the surprises that regenerate us within the warp and weft of our daily existence. The surprises that tumble us out into the next day something of a new person, with an opened mind and a gladdened heart that accompanies the epiphany of, “You do never know how something will go,” which can be a very uplifting realization.

I spar in my mind with myself over which film by the Archers reigns as the personal favorite, but I give the most thanks for 1944’s A Canterbury Tale, and it is the film above all others that I recommend to people as something they must-see. This movie of unofficial Thanksgiving is a Valentine’s from Michael Powell to his boyhood land of Kent, and the Old Road taken by the pilgrims so indelibly immortalized — with their archetypes fictionalized — by Chaucer in his The Canterbury Tales. It’s a time of war and uncertainty, but the film is a work gravid with peace and possibility — the favorable variety.

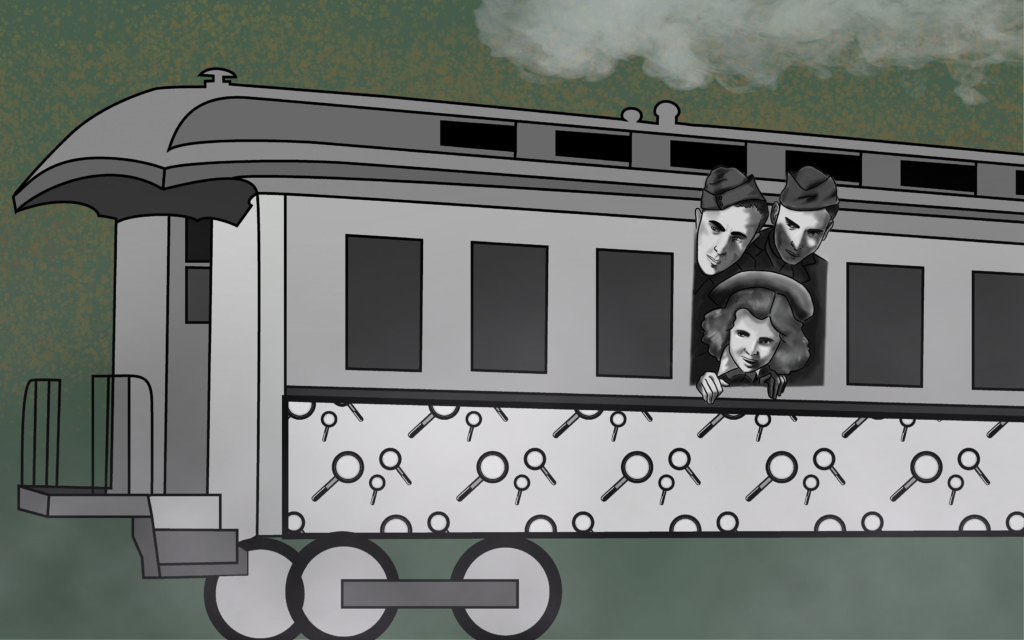

Three then-modern day pilgrims arrive not by cart or caravan to this fictitious Kent town of Chillingbourne, but rather via train. One is Alison Smith (Sheila Sim) who has come to Kent aiming to find a job as a sort of errand-girl of the land on behalf of a farm, as she feels connected to this spot where she once spent a week in a caravan with her late fiancé, a pilot believed to have been killed in the war. Sgt. Peter Gibbs (Dennis Price) is with the English army and is joining his squadron for maneuvers in the countryside before shipping out to combat. Finally, we have American Sgt. Bob Johnson (Sgt. John Sweet) who is on a three-day furlough and traveling to Canterbury to meet a soldier buddy presently boozing it up in London.

The train sequence has everything you want, full of darkness, lights shafts, the mystery of the night, but it’s a cozy mystery. Mid-century English films — and on up until 1964’s A Hard Day’s Night — excel at train-based work. It’s as if the English understand something about that mode of transportation that Americans at the time did not. The romance of a train, for instance, when one settles into one’s self, and visions of what awaits dance like shadows coming to life in the mind. Buster Keaton, I suspect, would nod empathetically, having made The General, but for all of its wistful qualities, Keaton is often outside of his beloved engine, riding atop her. The train in A Canterbury Tale is womb-like. These characters are about to be born — or born again. Which doesn’t mean religiously. There is no overt religion in most Powell and Pressburger productions, excepting Black Narcissus, and if you’ve seen that, you understand the asterisk we must apply to that movie’s concept of formal religion, given its sensuality. This “wombing” of us all — audience included — is crucial to A Canterbury Tale, putting us in a tabula rasa state, from which we’re open to anything that might follow — or more open than we otherwise would have been. We wish to sit in a compartment, engage in robust back-and-forth with a conductor. This is the day’s final train, and it feels like it. People say that Saturday has a feel, and a regular rider of the rails will tell you that the last train has a feel, too. The sensation is of being in a classic English mystery along the lines of Joseph Jefferson Farjeon’s 1938 novel, Mystery in White, but sans snow with humidity instead.

Cinematographer Erwin Hillier had a background in German Expressionism, and that background tells and tells well with this opening sequence. That movement served up a black-and-white lesson — literally in the color-contrast sense — of planar fields and the hard lines that separated one from another. It’s the art of juxtaposition, with two principle colors, but endless shades. Normally, this Expressionism is harsh; the style is not made for pleasant films that will have happy outcomes. Usually, that is. But Hiller’s tweaked/evolved German Expressionism is remarkable in that it allows room for English bonhomie, which you wouldn’t expect, given that medium’s standard austerity, but he makes sure we have the feeling of that aforementioned coziness. A child in the backseat of a car looks forward to the final stop of the journey, but then again, all is peace, safety, and comfort, and it’s so easy to doze with mom and dad up front.

We’re also a touch scared — on alert, the way one is on a train in an unfamiliar setting. You don’t wish to miss your stop, which is what Bob does when he accidentally gets off for Canterbury a stop early and ends up in Chillingbourne. The three friends who are not friends yet — though we detect the prefatory portion of friendship — are poised to say goodbye on the platform, with Bob now needing to locate lodgings, when a man in military dress bursts in out of nowhere, a fleet-of-foot shadow, and dumps glue on Alison’s head. This is the criminal of the village, the notorious Glue Man. His attacks are not infrequent and always centered on young ladies.

The idea of the Glue Man — who at once emerges as a shock, and yet blends into the night — tells us that big-time artists are at work. I recently watched an interview with an elderly John Sweet, from the turn of this century, taped in Canterbury in a simple, homey café resembling the one his character ends his journey at in the film — or starts his journey, I guess you could say.

John Sweet was a beautiful man, who spoke eloquently about art and what it could do for a person; the utility of art in improving lives. The practical application of art, let us say, which I think Powell and Pressburger were more interested in than other filmmakers. He talks about the film’s strangeness, especially the Glue Man business. He doesn’t mean strange as in, “this is bizarre, it couldn’t work” or “this strangeness makes for limited audience appeal.” He’s speaking to a kind of daring on behalf of the filmmakers. Life is strange. How often do we say, “You can’t make it up?” Well, what if you can? And what if in doing so, that unique creation, situation, character, narrative strand, segues with the seeming caprices of the fates that shape our respective life journeys? Our interludes? “Weird” or “strange” in great art does not mean “limited,” as those terms can imply elsewhere. Limited insofar as who might partake of them. Sweet meant “weird” as in true to life. And thus real, and thus believable.

Bob decides to stay in the town for an afternoon, which becomes a day, and in turn stretches to all of his leave, ostensibly working with Alison and then Peter on cracking the mystery of who the Glue Man is and putting a stop to his sticky madness. After all, it takes a lot of hot water to wash out the residue of his crimes.

The film is a mystery movie, but it is also not a mystery movie. There’s no stinting on the ratiocination, but the problem-solving aspect isn’t a case of life and death, blackmail, or the abducted child. It’s silly mystery. But also one that the three feel a duty to solve, which is also an excuse — or “reason” might be the better word — for each character to give themselves over to something larger than who they are, which they might not have otherwise. And therein come the surprises for which one ought to be thankful, and thankful that we position ourselves to partake of that surprise.

The imposed stop-over is a potent technique in the movie realm of Powell and Pressburger and potent metaphor. A halted journey is another’s start. Rare is the individual who knows this. Rarer still is the person who does something about it and commits to the second journey by understanding it is every bit the journey as the first, only more so, because it is the further leg, or it comes after a larger quantity of roads already traveled. There may be something invaluable to discover along this latest road, which itself is made more explicit in A Canterbury Tale by references to the Old Road made by Thomas Colpeper (Eric Portman), a gentleman farmer who loves learning and wishes to convey his knowledge on the area and its history to the soldiers passing through — men who, presumably, would have no interest in these lessons back in their lives, and also in their war. What I’m really talking about is a romantic. A romantic is open to the possibility that comes with change. They even think there is possibly magic to be had, if they adapt on the fly, if they open themselves up — if they “go there,” to put it a different way.

Pressburger wrote the treatment, and Powell the director largely brought it to life, or maybe I should say, put the film’s characters in a place to do so. The scenes with children playing at war — conscripted by Bob to gather intel in his efforts to identify the Glue Man — have a buoyancy to them that you’ll rarely experience in cinema. They evince charm, delight, humor, safety, and innocence in a world that has always lacked for both, and definitely did just then as WWII raged.

We are in John Knowles’s sanctuary land of a separate, cleaved-away peace, but Bob — the character who grows the most — becomes increasingly aware that the enclave of respite and restoration perpetually exists. The challenge is to find it and max out one’s life within it. And sometimes, the larger challenge is to know when one is already stationed inside of it, because, without that cognizance, the hamlet means little. In truth, it’s missed. Hidden in the plain view of despair, perhaps, or ennui.

Bob does not wish to depart the hamlet, but when he goes, he knows he will be better off. He gives thanks, though in the end, the unmasking of the Glue Man is bittersweet. Then again, the reveal helps to build to the movie’s extended climax/coda in Canterbury itself, as the three friends — and the unmasked Glue Man — all have business there.

There isn’t a more ingratiating performance — or I’m not versed in one — than that given by Sgt. John Sweet as Bob. You’ll fall for his voice and manner of speaking. He’s curious and invested in his curiosity. It’s a powerful way to live a life. What you won’t see is Sgt. Sweet in any other film, unless you want to count that documentary I mentioned in which he gives his thoughts much later on in life. It’s as if he came to Canterbury by way of Chillingbourne as Sgt. Bob Johnson and this was the one pilgrimage he absolutely had to take, that couldn’t be topped. Johnson became a teacher instead. For his role in A Canterbury Tale, he was paid $2000, the whole of which — and it stirs me to know this, knowing what I know of the character he played — he gave to the NAACP, no ordinary gesture for a white American man in the 1940s.

Powell and Pressburger are peerless in realizing what Orson Welles would term plotless scenes — extra bits that ostensibly do not advance the story, but are a story unto themselves, and aggregate such that they’re vital to how we understand the characters who are living the story. And that is what they’re doing — they’re not a part of a story, they’re not types in a story. They’re the story. Their natural lives and how they cogitate and choose orchestrates the story. The drama is compelling, and it passes for magical — there can be actual magic in a Powell and Pressburger film — but it also registers as natural. “Could have happened.” “Did happen.”

Alison stores her disused caravan for a decent fee at a garage in Canterbury. The boy’s father did not approve of the union that never came to be. They were well-off, she was a London shop girl. But she cannot let this vehicle go, and when she enters the caravan on the day when Bob and Peter and also Mr. Colpeper have also come to Canterbury — Peter to join his unit which is leaving for war, Bob to meet up with his outfit, and Colpeper to sit on the bench as a magistrate — and discovers moths have eaten the bulk of the contents, you want to cry for her.

But then the miracle occurs, which I’ll not spoil. If you know the film, we can debate whether it’s a true miracle, because after all, it does make a certain amount of practical sense, but this young woman’s expectations have transported her to a spot in her own heart where the news she receives — and where she is while receiving it — takes on the role of the miraculous.

Bob meets with his partying army buddy, and his miracle is quieter, but he’s a man more open to miracles in general now than before. We watch a bright guy acquire wisdom. The difference is sizable and singular. He’s further afield than the plane that his buddy occupies, though the latter has become something of an Anglophile himself, with his purview widened. These people are all changed, and we have observed them change.

The change developed out of a stopover, a mystery that could fit inside a shoebox. We don’t all have a Glue Man per se in our lives, but we do have the shoebox mysteries, and we do have opportunities to recognize the would-be miracle otherwise hidden in plain view. A Canterbury Tale is the movie that gives thanks to those miracles. And equal thanks to those willing to see them. •