As a burgeoning, avid collector of Beatles bootlegs, there was one record at the top of my wish list that I couldn’t wait to lay my teenage mitts upon. Rounding up unreleased music was no small effort at the time. One did not enter the name of whatever one wished to hear into the YouTube search field, for there was no YouTube, nor Google either. There was work to be done, a kind of industrious search, as if for the right partner in one’s life. This involved hours spent in used record stores — after finding a way to get there — and patience in flipping through the racks, or long chats with veteran collectors who always had a tall tale of some tape they had “heard of” but had not heard, and who laid the breadcrumbs which you could not wait to follow.

We had moved to a suburb of Chicago. I was a new driver, and I asked my father if he could chart a route for me to this one place in the city that he and I had visited together, where there was a row of record stores and, manna of manna, Beatles bootlegs that came from I knew where not. A wondrous warehouse. Japan. The other side of the rainbow. It did not matter, save that the mystery made the treasure all the sweeter, as did the certainty: that in the near future I would be sitting down and hearing music I loved, that challenged me, inspired me, brought me alive in ways seemingly beyond the ways of most earthly things. If that is not what all music does, it’s what this music did for me. Directly, and passionately.

To see a CD of the Beatles’ Stars of ’63 — an entry on the Swingin’ Pig label featuring the band’s finest concert from Sweden in October of that year — staring back in the display rack over the shelves was to know love, at least for me. The feeling was the same as when the girl ostensibly out of reach agreed to go to the homecoming dance. You lay up at night thinking about how it all went down, trying to get as close as you can to that feeling that you just had.

I have similar experiences now. Recently I came upon a recording from the BBC of the Who covering Marvin Gaye’s “Baby Don’t You Do It” days before the release of their first album in early December 1965. The BBC had wiped the tape. The song was recorded off-air by a fan holding up his or her tape recorder to the radio. It shouldn’t have existed, but it did. I sometimes feel that love is that way — a miracle which we see as something that happens or that we deserve or offer, and not out of the ordinary at all, though it always is, when it is real.

But these current experiences — taking place at a computer rather than in a shop — are connected to the ones from before. Perhaps love is also this way. We meet the person we will spend our lives with, but we know how to meet them — how to come to them — as a full infusion of everything we are, how to be with them, in part because of a journey of knowledge that began with the girl on the playground in third grade, and the high school sweetheart, who, in the words of F. Scott Fitzgerald, “may be dead or some man’s mother.” Or the ex-wife.

This is how I have listened to and known music in my life, and all art. It’s how I’ve made it as well. But I mentioned there was one bootleg I was especially keen to track down, and that was the Beatles’ complete appearances on The Ed Sullivan Show. The reason might not be what one would think.

The Ed Sullivan performances are underrated. They’re typically discussed in the context of what those first appearances from February 1964 — when a nation effectively met these young men — meant as a seismic event in American pop culture, and culture itself, in following from the Kennedy assassination of November 1963.

But they also hold up as dynamic art — you can listen to them repeatedly, the same way you would A Hard Day’s Night or Mop Top-phase Beatles singles such as “I Want to Hold Your Hand” and “She Loves You” that contain as much energy — the Beatles’ purest strength as artists — as any existing work. For while genius may be comprised of an infinite number of component parts, energy is deeded as much space as anything. It’s the life force of human witnessing, growth, and connection, and it makes all great art move like only all great art can.

The bootleg I acquired on my treasure hunts was called Conquer America, an apt title and a manner of conquest one welcomes. What I wanted to lock in on, though, was an Ed Sullivan Beatles performance taped August 14, 1965, the day before their first appearance at Shea Stadium. The Beatles had arrived at the Help! portion of their career, with songs of overt introspection first hinted at on the second side of A Hard Day’s Night, and then developed further with the pop-burnished confessionals of “No Reply” and “I’m a Loser” — and its lived-in country twang — on Beatles for Sale.

Paul McCartney, who always sang “Yesterday” like he meant it, even later when the rest of the band went through the motions in Tokyo in 1966, seemed to do so on this day with a level of emotion that was practically tactile. You feel like you could blot up the residual sincerity that must have manifested on the stage underfoot. Having finished, his partner John Lennon, both suppressing and showing a touch of his urge to quip, remarked, “Thank you, Paul, that was just like him.”

This statement, which I had read about before I heard it expressed, fascinated me. Lennon was speaking to “Macca” and to us simultaneously, but as if betraying no confidences — everyone was being let in on a secret just for them, which others could experience. This was intimacy, out in the open. Naked friendship, and one person — who was no casual dispenser of kind words, compliments, or feelings — letting the world in on what it was they loved about their friend, in a clever, shaded way, so that not only could you understand it, but it’d resonate even more.

Lennon speaks the words, but they might as well be sung — it’s the Beatles’ brand of Liverpudlian recitative. There are Lennon zingers, and there are Lennon truths. Sometimes they were the same thing. He was one of those rare people and artists whose oblique statements somehow found their way faster to the human heart. The elliptical Lennon could fire his arrow to make Robin Hood wonder what he was doing out there on the same field, failing to hit the target with similar accuracy.

That was a special trip for me to the used record store, and I have never stopped thinking about this entrenched rapport of love — expressed pithily and completely — between two men who also wrote some of our finest love songs, and two in particular, that we might say are just like both of them.

We don’t talk about love songs like we used to. The concept of what the love song could be once represented an apex in songwriting — to write a high-level love song was to be a remarkable songwriter. A love song of a certain caliber was viewed as possessing universality, but without a common cheapness; that feeling of specificity that a listener believes speaks directly to their own experiences, more than anyone else’s, while also knowing that others — millions — feel the same way, which in no way undermines the personal element.

There was also the idea that a love song conveyed universal truths, regarding the fundamental universal concern, or that which comes closest to one — the desire to be loved. The American songsmiths — Irving Berlin, the Gershwins, Cole Porter — could be clever, they could cover all forms of subject matter — but when we speak of their genius, we speak of their love songs. If their music is timeless — and it is — it’s because the desire to be loved is as well.

Simultaneously, the love song was a challenge: Can you write one of these? Not a soppy one, but a love song with a holiness-on-earth, that found a new way to describe, capture, and make a listener feel a component that is in all of us. Love songs raised the bar of the possibilities of songwriting. They were the songs, potentially, of forever.

Lennon and McCartney came of age as songwriters with this ideal in mind, which was first out of their grasp — “Love of the Loved” and “Thinking of Linking” weren’t going to get them there — and then attainable, as their talents progressed. They were as much fans of Tin Pan Alley songwriting as were Chuck Berry and Elvis Presley, both of whose early recordings owed much to Tin Pan Alley — the actual writers from Tin Pan Alley in Elvis’s case, who gifted him material, and the emphasis on poetized, short story-type lyrics that told stories in Berry’s.

McCartney satirized just how resolutely he’d become associated with this form of writing on 1976’s “Silly Love Songs,” a number which has seldomly been understood as satirically intended. Like “Wonderful Christmastime,” it’s a McCartney tune people make fun of, in part because these efforts from the 1970s aren’t of a piece with what McCartney did so regularly in the 1960s. Despite being in his 30s, the connotation was that this was “old” McCartney — the fuddy-duddy, not the bird of artistic prey.

Beatles fans in 1977 would have had an interesting year, rather like Beatles fans in 2021, with the release of the Get Back docu-series. A portion of the December 1962 Star Club recordings from Germany was issued as a gray-market release — that is, the legality was dubious. The Live at the Hollywood Bowl set also came out in 1977, which must have been thrilling, as most Beatles fans had never heard the Beatles live, unless they had been around to watch them on The Ed Sullivan Show or gone to a gig themselves. And then there was a double album called Love Songs, a sort of thematic follow-up — albeit in a different mode — to Rock ‘n Roll Music, a compilation of the band’s barn-burners from the year before, which is quite a solid set that most Beatles people are unaware of. But it was Love Songs that was adamant in putting forward a Beatles-based case that these guys could reach that same apogee as Berlin, the Gershwins, and Porter; nay, that they could even extend it.

I love this compilation, partially because it’s so weird. It ought not to work, but it does work. I say it shouldn’t, because it leaps all over the place, and it’s quirky. Regarding the latter, “I’ll Be Back” from A Hard Day’s Night is here (as is George Harrison’s naïve, sweaty-palmed “I Need You” from Help!), despite being a veiled threat, and not a very veiled one at that. It’s a comeuppance song like Led Zeppelin’s “Your Time Is Gonna Come,” but one that also allows for romantic possibility. There’s nothing to say, Lennon also seems to say, that these reunited lovers can’t put problems — or distance — behind them and make a happy go of it.

Again, it’s that elliptical Lennon, and this is an elliptical double album, concluding with “P.S. I Love You” — a decent enough McCartney composition, which shone more with promise than payoff — from the band’s first LP, Please Please Me, having followed “I Will” from 1968’s The White Album. Crazy juxtaposition, moving from that end-of-career period back to the fecund beginning. Somehow, it coheres, much like the Ultra Rare Trax bootleg series of pristine studio outtakes that emerged in 1988. The jumps in temporality prove weirdly winning. The Beatles had a hard time screwing up, even years after they had ceased to be. Or maybe I should say it was hard for anyone — record company executives included — to screw them up.

On Love Songs, tracks that don’t appear to belong together as workable fits, reach across the years and styles to become bedmates. Odd couples — but couples that work well together. This is Beatles alchemy, extended past the end of their own career, finding new form on a compilation that attempted to resurrect the love song. Remember, this was a time period of disco and punk, and while those styles were linked in no musical manner, save that the latter would have liked to garrote and gut the former, love song did not spring forth from either genre. The Beatles of ten years before, as love song fashioners and purveyors, would have been seen as distant but present — Bardic, and embossed with presumed wisdom, but also in the room, because the Beatles had never truly gone away.

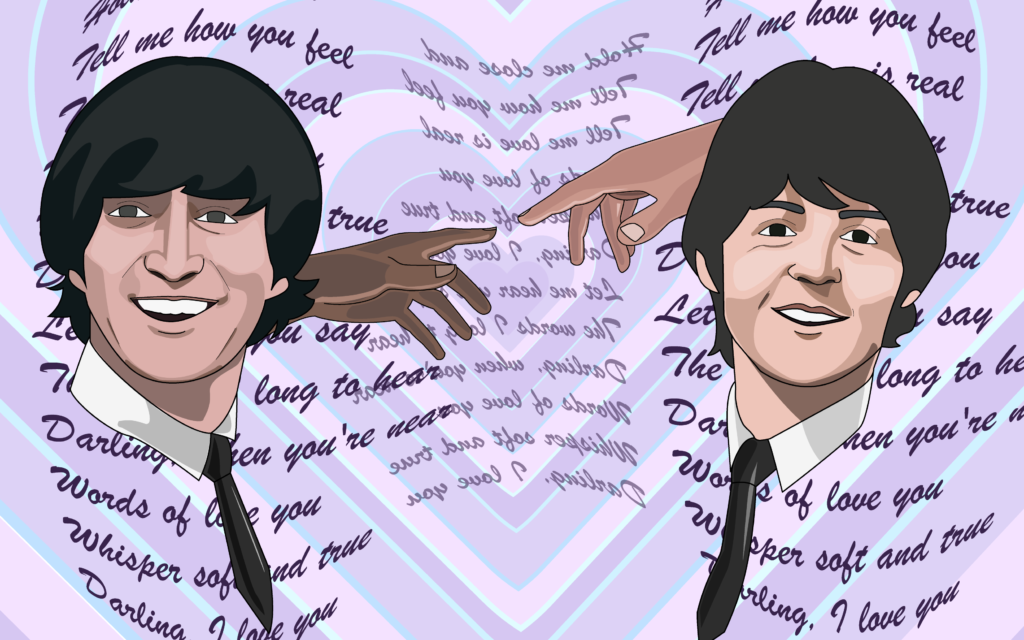

On the first side of the compilation, there are two lovers trying to touch, as I like to think of them, with the single best love song ever written by John Lennon, separated by but one track — a matchmaking cover of Buddy Holly’s “Words of Love” — from the best love song ever written by Paul McCartney. They are dissimilar, as the composers themselves were as composers, but they function along similar songwriting ideals, which is different than techniques.

The Lennon song is “In My Life,” a number he struggled to compose, at a time of his own life when he peaked as a songwriter. We all know accounts of “Gee, this idea hit me and boom, out it came.” McCartney spoke of the melody to “Yesterday” this way, and was incredulous that he had invented it. But there may also be power in struggle, in the challenging birth. The journey to a fully-formed work of art. Rubber Soul is the peak of Lennon’s artistry. I have always thought of it as his album. The record also marked a coming change in the dominant songwriting force within the Beatles. After Rubber Soul’s release, in December 1965, McCartney will be leading the writing way for the band. Lennon has been the main guy over these crucial early years, and now to the mid-point. That’s one reason why I esteem the early Beatles as I do. As a force of artistic energy, I don’t believe there is anything that rivals their music of the period 1963-1965. A lot of that is Lennon.

He was in elliptical mode, as he wrote the song, which is tantamount to an early version of a “Penny Lane” or a “Strawberry Fields Forever,” from 1967. Those were numbers that looked back for the purpose of growing forward. They inhaled and breathed the air that is the circulating stuff of pure childhood freedom and invention. You can feel that air in the lungs of those songs, and in the outward expression of the lead vocals, which, too, have their apogee aspect. Lennon was already there in 1965. “In My Life” is the dry run for “Strawberry Fields Forever,” but as a piece of cod-Baroque music, with Edwardian inflection, rather than outright psychedelia and the dream calliope of a Lewis Carroll character awakening to a second chance at the possibilities of childhood, and the magic contained therein, and the magic that period may lead to.

Lennon began to write “In My Life” with a veer towards maximalism (“In My Life” was on the road to becoming a proto-“I Am the Walrus”), creating a hodgepodge of a song checkered with Liverpool landmarks, people he’d known, a who’s who and a what’s what. But I mentioned that this was Lennon at his best, and Lennon at his best realized that a little bit of Lennon would beat anyone else’s “more” of anything else.

Robert Johnson called this, “the stuff I got.” That’s a crucial discovery for the finest artists, and I believe that every last one of them has this epiphany. Art becomes not about reaching and straining, but trusting in the gift, and, simply, showing up, and being one’s self. Can be harder than it sounds, for this is a faith-based endeavor. You have to know what you got. You have to trust that it will always be there. You have to know that simply being you is going to carry the hell out of the day.

I think we can say that relationships are not dissimilar. Conceivably, what I’ve said about making art is also what makes love work, in all of its guises, and allows people to connect with each other sans barriers, or manufactured selves that add degrees of separation. Again, harder than it sounds.

Lennon jettisoned the references, culled his word salad, and found his feast, inviting us all to his banquet table with a love song that seemed to love us more, just as the singer loved the subject of the song. Who is she? Who is he? Who is it? I ask, because I think the love is that idea of love, of the total connection. An ideal that may be made actual. That is actual. How do you give that actual ideal name and voice? You write and sing a song of this nature. Let us be elliptical, but true: She is love, and that love out in the world — a human — that one might also be writing about, is contained within her, where she is also free. I am moved to say, “Thank you, John. That was just like you.”

As Rubber Soul was for Lennon, so would the following year’s Revolver be for McCartney. It’s amusing that George Harrison would confuse the two records, saying that what was on one could be on the other, as if they were Radiohead’s Kid A and Amnesiac. Rubber Soul was English folk crossed with American soul, with rustic ballads or ballads suggestive of an oak-paneled downtown London apartment whose occupant has nipped off to the Royal Albert Hall for a Sunday classical matinee after smoking a joint. Revolver was the alien album, beamed in from another world, or launched from this one into another, but with distinct overtones of a certain Englishness. If any Beatles record has the whiff of afternoon tea — and rocket fuel — it is Revolver.

McCartney was that culture vulture, the man-about-town just back from the Berlioz performance at the Royal Albert Hall, and the Beatles’ resident intellectual sponge as Lennon dosed himself on repeat in his LSD-addled days, culminating sonically in the cyber-electro brainstorm of “Tomorrow Never Knows,” an ancient and future sound of infinite synapses firing. If we want to be as basic as possible about it, on Revolver, Lennon was loud and McCartney was soft. One man was in rippling motion, the other was actively thinking, which is itself a form of action, or can be, if one is Paul McCartney in 1966.

“Eleanor Rigby” is an existential love song for the lonely, and “For No One” is the love song Schubert would have composed if he’d been born in the north of England in the late 1940s, but if McCartney is the perfect rock and roll writer of love songs, then “Here, There and Everywhere” is his creation of perfection. Love Songs itself moves from “In My Life,” to the Buddy Holly cover, and then to this piece, which shares Lennon’s approach, but not his technique. That approach is one of directness, but Lennon took a while to locate his route, paring away what he did, whereas McCartney began and ended with that directness and faith in his own ability.

“Here, There and Everywhere” never becomes repetitive, no matter how often one listens to it, and yet it seems to be made from so little. There aren’t a lot of words in the thing, and the lines are similar, tweaked by a word in most cases, and that is all. The man’s confidence was outstanding. He knew exactly how good he was, and had the faith to trust his ability and let it do the work. Lennon was as good in his manner, but he didn’t trust himself like McCartney did.

The melody rises upwards — that’s its directional flow — as the song builds. I think of it as tantamount to Thomas Weelkes’ “As Vesta Was Descending” in reverse, altitudinously speaking. We also get George Harrison making contributions on guitar that are never discussed. A solo wouldn’t work here — which is generally a truism about love songs; George Martin’s chamber music piano on “In My Life” feels like an additional voicing, rather than an isolated one — but the lightly percussive touch to the guitar provides both crucial rhythm and certain lipstick traces.

McCartney’s vocal is a wonder, too. It sounds like a falsetto, but it’s not, when you listen closer. It sounds like he’s singing-whispering, but he’s not doing that either. Listen to the first take of 1965’s “Yes It Is” in which Lennon, forgetting the words, or not caring about the words — as the band was really just trying to learn the song at that point — starts doing this form of mumble-singing, singing via humming, the way we do when we’re embroiled in a task during our day and a tune comes to us. It’s a touching, naked moment — it’s really just missing a showerhead and some steam — and one of those unreleased Beatles cuts I treasure on account of the intimacy and how easy it is to identify with it, and hum-sing along as well, if one wishes.

This is how McCartney sings “Here, There and Everywhere,” but with the hum-sing — which resonates as a sacred, informed whisper of love — as a vocal proper. It’s wild. And it’s still rock and roll, but a quiet kind that is emotionally loud. When we have desires, those desires are telescopic. They have parts. A first wish produces an understanding that leads to an extension — the second part of the wish. I don’t just want to be with her, for instance, I want us to have this kind of life. A child to make us a family. Another. Children who are happy, who increase our happiness. And so forth.

The telescoping of love. That’s exactly what “Here, There and Everywhere” is in musical form. The verses progress; the singer wants his beloved first here, then there, and finally omnipresent. The song is the ultimate work of “less” from McCartney, and as a result, “Here, There and Everywhere” feels like it is everything its composer was capable of or any genius composer.

I have always liked the idea of these two Beatles love songs being so close to each other on Love Songs, like they’ve been set up for a date and are now approaching the café where the coffee will be consumed from different ends of the same block. I root for them. The movement they need — and ply — is in their large-heartedness. They are, themselves, just like what love can be. •