Charles E. Merrill, founder (with his friend Edmund C. Lynch) of the famous brokerage firm, probably never read this comment by President John Adams: “I must study Politicks and War that my sons may have liberty to study Mathematicks and Philosophy. My sons ought to study Mathematicks and Philosophy, Geography, natural History, Naval Architecture, navigation, Commerce and Agriculture, in order to give their Children a right to study Painting, Poetry, Musick, Architecture, Statuary, Tapestry and Porcelaine.” Engaged in “Commerce,” Charles Merrill might have expected his son to follow suit, but, when young Jamie said he wanted to be a poet, his father, according to sound investment practice, sent a sheaf of poems to literary experts for an opinion. Assured that this aspirant had talent, the senior Merrill, in good John Adams fashion, abandoned any opposition and supported his son’s artistic ambitions. With that talent and a very large fortune in hand, James Merrill went on to become one of the most famous poets of his time. He briefly held a desk job in the Army, and several times accepted to teach college poetry-writing courses, but otherwise never took any salaried work. His bank account gave him unlimited access to things that can feed literary composition: education, travel, theatre, books, music, art, porcelain, and the company of other established artists. Someone could write a Ph.D. thesis on the role that inherited wealth has played in the history of American poetry. James Russell Lowell, Amy Lowell, Robert Lowell, Elizabeth Bishop, James Laughlin, Isabella Gardner, Frederick Seidel, and Harry Matthews all, with varying artistic results, benefited from it. As did James Merrill. Not only does money talk, it also sometimes writes poetry.

Merrill was gay and could be fairly certain that there would always be young men interested in him — but in varying degrees and with differing motives. A high percentage of his work is love poetry, the aching uncertainties and reversals of love providing requisite dramatic interest, since most other problems could be solved by signing a check. But like all rich people Merrill suffered from a nagging anxiety: “Are they interested in me or what I can do for them?” That anxiety could also be expanded into the question of whether poets and critics who professed interest in his work did so because of its intrinsic value or because they hoped to gain some sort of advantage. On the other hand, leftwing critics could be expected to attack him simply on the basis of his inherited privilege, whether or not his books happened to be good. Hammer’s exhaustive biography makes it clear that Merrill’s fortune, though it gave him the means to succeed, was also the source of several kinds of doubt and frustration.

Read It

James Merrill: Life and Art by Langdon Hammer. Available now from Alfred A. Knopf.

I should state that I appear fleetingly in the final chapters of this biography as someone who knew Merrill well. Further, the author Langdon Hammer was in a class I taught at Yale in 1977, and we have been intermittently in touch since that time. In fact, he interviewed me as part of his research, though little of what I recalled has been used. So I will just comment on what is (or isn’t) in the biography rather than trying to arrive at an estimate of its value. Anyone can see, though, that a book running to more than 900 pages and containing dozens of photographs, excerpts from Merrill’s journal and personal correspondence, plus extensive end-notes, obviously qualifies as a staggering work of research, indispensable for scholars and critics of Merrill’s poetry.

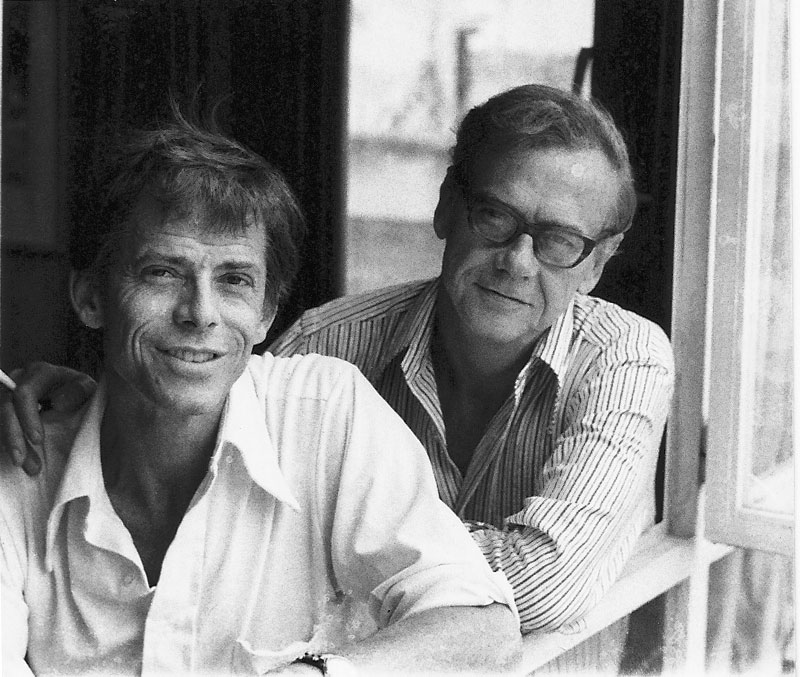

Exactly what will interest the “common reader” is less certain, though expensive place-names like New York, Southampton, Venice, and various European capital cities usually excite curiosity. Not to mention the parade of celebrities who make cameo appearances or come for longer stays: Robert Frost, Tennessee Williams, W.H. Auden, Truman Capote, Mary McCarthy, Leonard Bernstein, and practically every notable poet of the era. Not particularly star-struck himself, Merrill tended to prefer his less famous friends — or lovers, as some of the former often began as the latter. David Jackson, who was his partner from the early 1950s until Merrill’s death in 1995, dabbled in several artistic pursuits, but never excelled in any and would have no claim on our attention except for his relationship to Merrill. What began as a romantic affair soon evolved into comfortable domesticity when the two left New York and settled in Stonington, Connecticut in 1955. Jackson had no family money, though, and after settling down with Merrill only twice held brief salaried positions as a teacher of writing. We have to assume he was subsidized by his partner, and it would be interesting to know whether that involved a monthly stipend or a sizable fortune settled on Jackson early in their relationship. If he received a lump sum, then Jackson clearly stayed with Merrill because he wanted to, not because of the meal ticket. It doesn’t appear that he owned any of the residences they shared except for a Key West house he bought late in life. Another reason for his decision not leave would be for the pleasure of social life with literary and artistic friends Merrill could always depend on having. But at the peak of Merrill’s fame, when large numbers of fans and wannabes poured in, you sense that it all became too much for Jackson, who was relegated to the uncomfortable position of being a celebrity “wife,” of no special interest to the newcomers.

Early in their relationship, both men began, with mutual consent, to look for sexual encounters outside their unconsecrated union. That won’t shock gay readers, who are aware that it is a common practice for gay couples who have been together longer than, say, five years. In most cases the couples are childless, so possible damage caused by “infidelity” and the risk of eventual splitting up is limited to the two directly involved. Less common is what developed with Merrill and Jackson. No longer attracted to each other physically, they began making annual visits to Greece in the early 1960s, mainly because of the availability of young Greek men. Though not gay-identified, these penniless soldiers and workmen were willing to exchange sexual favors for presents, wine-saturated dinners, weekend trips, and occasional cash donations. Sexual tourism is in our time frowned on, but there are many precedents, for example, Flaubert in Egypt, Gauguin in Tahiti, Gide in North Africa, Jane and Paul Bowles in Morocco, to mention a few.

But then Merrill fell in love with one of his pick-ups, a young, straight-identified man named Strato Mouflouzélis. Love hadn’t entered the picture before, and it alarmed Jackson, who feared it might be the end of the couple. Seeing eventually that there was nothing to fear, he calmed down enough to form a steady relationship with one of his own boyfriends. The Merrill-Jackson long-term double date worked for nearly a decade before the force of circumstance swept their Greek partners away. This development was followed on Merrill’s side by a series of love affairs, consummated or unconsummated, whereas Jackson contented himself with temporary partners. Merrill could always find brief encounters in Greece. The unconsummated counterparts involved Americans in two categories: one young painter, who, though gay, felt no attraction to the much older poet, and one young scholar-critic who was straight and unlikely to be attracted to a man of any age. Both the consummated passing fancies in Greece and the unconsummated American prospects resulted in new Merrill poems. Love might not always be returned, but the ability to transform it into lines of verse remained constant with him. Happy ending or no, a new love affair provided usable dramatic ingredients, at least for an author who had the means to set the stage. A later poem “Matinées” remarks:

The point thereafter was to arrange for one’s

Own chills and fevers, passions and betrayals,

Chiefly in order to make song of them.

The biography reports the feelings of some of Merrill’s subjects, but not all. By a speculative leap, it’s possible to imagine that the American subjects were flattered to be immortalized, despite some infringement on their privacy. As for the Greeks, they didn’t speak or read English, so there’s little chance they were aware of being written up. The one possible exception is a man whom Merrill brought to live on a lower floor of his Connecticut house, along with the man’s wife and children. Having served as both handyman and sex partner, the hardworking immigrant learned English and became an American citizen. He or at least his children might later on have read Merrill’s poem about what he called his “Holy Family,” but their reaction isn’t reported.

Hammer provides astute new interpretations of some of Merrill’s fiction (he published two novels) and poems, showing how life impinged on art in the oeuvre. There are a couple of purely factual questions I would like to have seen resolved. There were two privately printed volumes of Merrill’s verse that appeared in the 1940s, but he did not have a regular publisher until Knopf brought out the 1953 First Poems. It was printed in a numbered edition, something trade-book houses almost never did, even in that era. The story current during his lifetime was that Merrill had subsidized the publication. It would have been helpful if the biographer had confirmed or disproved the rumor. In any case, this debut launched a long and successful publishing career that included more than a dozen books of poetry, two novels, and a collection of critical essays. Merrill also wrote two plays, both of which, with financial assistance from the author, were mounted in New York. He also produced a film version of his Ouija epic (at a cost, Hammer estimates, of $800,000). It’s hard to think of any American author who produced so much work in so many different genres, though of course there may have been writers equally productive and diversified, yet without access to venues for their work.

There was considerable critical resistance to Merrill’s early books, but in 1968 Merrill was awarded the National Book Award for Nights and Days. Judges were W.H. Auden, James Dickey, and Howard Nemerov. Both Auden and Dickey were acquaintances, if not close friends; and Nemerov had favorably reviewed an earlier Merrill volume. At that time, a panel more favorable to him could hardly have been assembled. We might be surprised at the judges’ indifference to the charge of favoritism, but that sort of decision was quite common in the decades before 1990. Randall Jarrell had been one of the judges awarding the Pulitzer to his close friend Robert Lowell’s first book, for example, and Lowell was instrumental in awarding the same prize to Elizabeth Bishop’s second. Prizes have a way of snowballing. If you win the NBA, it’s fairly certain a subsequent work will get the Pulitzer and other awards, just as Merrill’s did. With some of the later honors, again, the judges were close associates of his. That doesn’t prove the books were undeserving, but it does make you wonder why his friends didn’t avoid the risk to his reputation (and their own) by giving the prize to a poet they didn’t know personally. You could of course argue that the poetry world in those years was rather small, more like a little moon than a world, and that, in varying degrees, nearly everybody knew everybody else. When poets weren’t friends that was usually because they were enemies, and an enemy’s judgment doesn’t qualify as impartial, either. Writers choose their close associates carefully, avoiding alliances with people whose work they consider inferior. What might look like mere cronyism could be accounted for more benignly: the judges chose the book they sincerely admired, unhindered by their friendly association with the author.

Hammer sketches in the establishment and operation of the Ingram Merrill Foundation, which annually distributed grants to individuals and groups that might have been overlooked by older funding institutions. He says that very poor records were kept, so that a complete list of grantees can’t now be assembled and certainly not a tally of applicants who were turned down. It seems that Merrill didn’t endow the Foundation outright; instead, grants were paid for out of his own annual income. I was aware that the board making decisions was composed of Merrill himself and his friends; and Hammer acknowledges that the poet’s preferences were always honored by the other panelists. The Foundation was Merrill’s way of dealing with constant requests for money. He could simply tell requesters—those he liked and those he didn’t—to apply for a grant. Then, if the application didn’t succeed, blame could be referred to the other judges. As a former successful applicant myself, I can state that the process wasn’t laborious, and the award only confirmed my sense that Merrill approved of what I was writing. In my professional life, if I’d only received one grant, it would have been no great surprise. But in fact there were two, a decade apart, which now seems to me excessive. Some applicants received even a larger number. There’s no question that the Foundation assisted many deserving artists, organizations and critics. In the absence of an endowment, though, it was dismantled after Merrill’s death, a serious loss in a period when public funding for the arts is drying up.

Hammer mentions in passing but doesn’t investigate in detail another factor that has a bearing on Merrill’s public life. In the early 1960s he was approached by Barbara and Jason Epstein as a potential investor (along with other affluent friends of theirs like Robert Lowell) for a new publishing venture. This was what became The New York Review of Books, the most prestigious literary-political journal of the following decades. More than 10 years of publication passed before a book of Merrill’s was reviewed there. But after the National Book Award, all were, and he was invited to publish poems and articles in the magazine as well. Editors must have felt that since he had earned his stripes elsewhere, no nepotism was involved in favoring his career in the pages of a magazine he owned a percentage of.

There is more. His friend Howard Moss, poetry editor of The New Yorker, sincerely admired and accepted many of his best poems for it, some of the poems very long. And then Daryl Hine (whom Merrill had helped on his way to becoming editor of Chicago’s Poetry) was always eager to publish him and assign his books for review. For poets, these were three of the most influential magazines of that era. The New York Times, favorable to Merrill early on, became unfavorable during Harvey Shapiro’s editorship but, as time passed, began to support him again. All of which helps explain how this author, who did not have the earmarks for popular success, ended up extraordinarily famous. There were veiled or open objections to the fact that he was a rich, gay author of poems that depended on rarefied cultural references. Further, he could be ironic to the point of cynicism and sometimes mocking toward a poem’s cast of characters when they were not as well-educated or well-fixed in life as himself. Features like those do not win over the largest percentage of the contemporary audience. The ideal American author is a heterosexual male, a two-fisted outdoorsman who doesn’t put up with crap from any Aunt Sally who wants to “sivilize” him. That these qualities weren’t mentioned by John Adams in his list of desirable artistic goals points up a shift in American culture that began in the late 19th century and became permanent thereafter—at least until feminist perspectives began calling it into question.

Actually, when Merrill received the Bollingen Prize (administered by the Yale Library), an Op-Ed appeared in The New York Times protesting the award—unsigned but later identified as the work of Thomas Lynch:

Mr. Merrill is a poet of solid accomplishment and sure craftsmanship. The quarrel is not with him but with the Library’s insistence down the years that poetry is a hermetic cultivation of one’s sensibility and a fastidious manipulation of received forms. The Bollingen people flinch from poetry that is raucous in character or that has an abrasive public sound, from poetry in the Whitman tradition or poetry that is experimental, from the poetry of black writers, much of it now very visible and vocal.

The editorial acknowledges that Merrill is a solid craftsman, and certainly that aspect of his work accounts for his appeal to a cultivated readership. Yet it has always struck me as an error when Merrill is described as a defender of high culture and tradition, given how often he makes fun of those things, even apart from the default subversion of normative sexual behavior. In his poem “The Thousand and Second Night” he says:

The day I went up to the Parthenon

Its humane splendor made me think So what?

The same poem includes ironic digs at Yeats, Valéry and Eliot, plus this:

You’d let go

Learning and faith as well, you too had wrecked

Your precious sensibility. What else did you expect?

It wouldn’t be easy to find even in the work of the Beat Generation dismissals so crushing, and the poem tells that his friends have come to regard him as a “vain, flippant monster.” It’s clearly time for critics to reconsider his reputation as a pious traditionalist, on his knees before Western Civ’s “monuments of unageing intellect.”

One aspect of his work I would single out as helping to explain his popularity is Merrill’s comic flair. It began to surface in the anthology piece “Charles on Fire” from Nights and Days, as well as in lines and phrases from other poems in the same volume. Throughout Merrill’s writing, you discover the same sort of satiric wit associated with writers like Byron, Wilde, Vidal, and Capote, and few things are more crowd-pleasing than a well-phrased putdown. By the time Merrill began writing his Ouija board epic, it was a dependable resource in his poetry, confirmed by the character Ephraim, the familiar Ouija spirit who guided Merrill and David Jackson through the labyrinth of the Other World. Ephraim makes witty and deflationary jokes about almost every topic that arises. I’m hard put to think of anyone in the real world as witty, except for Merrill himself.

When “The Book of Ephraim” appeared along with other longish lyrics in Divine Comedies (1976), Merrill hadn’t planned for it to be the first installment in a three-part epic running to more than 17,000 lines. But then reviews praised the poem in ecstatic terms, one result of which was the Pulitzer Prize. After all that, no one should be surprised that Merrill decided to obey instructions from the board and push the Ouija project further. The result is The Changing Light at Sandover, one of the strangest poetry volumes ever published. It’s an endeavor that still divides critical opinion. Advocates consider it the breakthrough book that allowed Merrill to deal with issues of burning importance to the modern world like nuclear destruction, overpopulation, and the environmental crisis. For readers of a New Age bent, it also provides material for cosmological or mystical speculation. For those who believe in an afterlife and/or reincarnation, the board’s Other World offers evidence that they are right — so long as no one doubts the messages entrusted to Merrill are a reliable source, reproduced exactly he received them.

Detractors have said that, despite lyrical passages drafted in Merrill’s voice and despite the book’s comic appeal, it is longwinded, not to say boring; that the spirit voices recorded don’t write as well as he; and that much of what they say is demonstrable nonsense. Some have objected to the board’s depiction of deceased figures like W.H. Auden, remarking that the afterlife seems to have transformed them into flea-circus versions of themselves. Not consciously in control of what the board says, Merrill himself probably couldn’t be blamed (though perhaps his fellow-medium David Jackson might be) for remarks presenting historical figures like Hitler and Stalin as somehow necessary in a universe where there is “no accident.” It would also be hard to locate responsibility for the racial bias that occasionally crops up during the Ouija seances. Another writer might have cut these remarks, but Merrill left them there in a “dictated” work of which he was the sole editor. The epic is either profound and entertaining or a ghastly, over-the-top mistake, depending on the reader’s taste. Hammer clearly supports the epic, but in my estimate Merrill’s best work is found among the shorter poems.

It’s not possible to cover every issue raised in a biography of 900 pages, and good reviewers focus on those points where they have some authority. I would like to clear up one misapprehension in which I was directly involved. On page 734, this is said about Alfred Corn: “He was heard declaring (in Merrill’s annoyed version of Corn’s comments at a prize ceremony). ‘In these terrible times poetry has to be more than a mere Mandarin manipulation of language.’” Those terms aren’t in my critical vocabulary; nor is this an accurate description of my views of Merrill’s poetry. The word “manipulation” appears in the Op-Ed piece cited above, which had a searing impact on Merrill and obviously stayed in his memory. I am and was then certainly aware that serious topics like the nuclear threat and environmental destruction had been a notable part of the Ouija epic’s thematic content as well as in several shorter poems. As for “Mandarin,” if it means a concern for the kind of cultural continuity discussed in Eliot’s essay “Tradition and the Individual Talent,” then my work is equally “mandarin.” Using a word with pejorative connotations to designate this aspect of literary texts strikes me as unthinking.

What actually happened is this. The prize ceremony mentioned was sponsored by the Academy of American Poets and scheduled for late winter, 1990, at the Guggenheim Museum in New York. I, along with Marvin Bell and Sandra McPherson were judges that year for the Lamont Prize, which we agreed should go to a book by Minnie Bruce Pratt titled Crime Against Nature. The other award being presented on the same occasion was the Whitman Prize for a first book, judged by W.S. Merwin and given to Martha Hollander. Her father John Hollander and Merrill, who were both Chancellors of the Academy, were present for the ceremony. Pratt took the occasion of the award to make a political speech, its progressive, perhaps radical content welcomed by some members of the audience and despised by others. Clearly both Hollander and Merrill disliked it because they began passing notes to each other as the speech continued past the five-minute mark. Hollander understandably didn’t want the occasion spoiled for his daughter, and Merrill may have thought the political speech was aimed at himself. Because I was the only Lamont judge to attend that night, the burden of responsibility seems to have been placed on my shoulders. Quite possibly Merrill assumed that awarding the prize to Pratt’s book amounted to a veiled attack—hence his misattribution of those negative judgments. He had decided the previous year to end our friendship, so on this occasion the only encounter between us occurred during an accidental meeting on the stairs leading down to the Guggenheim auditorium. Face to face, he could hardly avoid speaking, but all he said was “Hello, Alfred,” as he smiled ironically, reached out a hand and took a fold of my cheek between knuckle and thumb, to give my face a shake. Otherwise we did not come within earshot of each other during the entire evening; and in fact never spoke again.

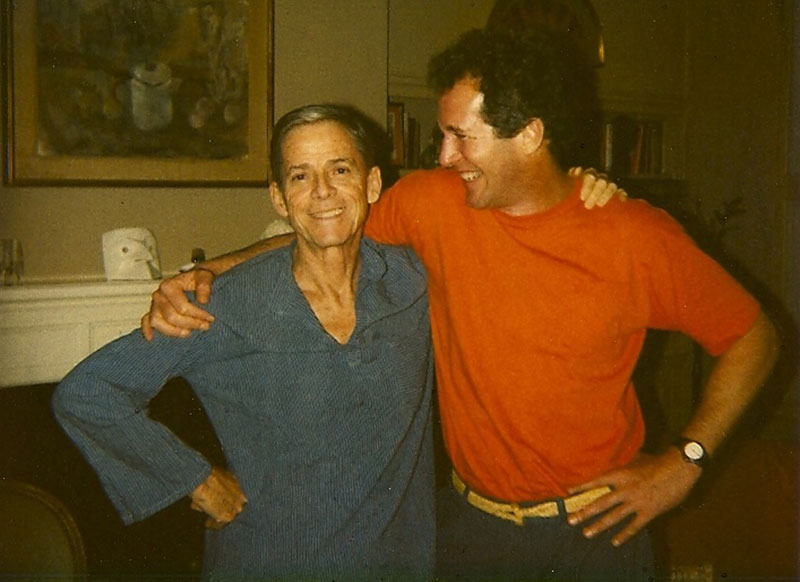

Various “pathographies” published over the past several decades have accustomed us not to expect pristine behavior from artists, and Merrill is no exception. I think some of his best behavior, though, came late in life, after he tested positive for HIV. In the 1980s, that usually amounted to a death sentence, to be carried out within a year or two of the diagnosis. As things developed, his life continued without major medical problems for nearly ten years. He didn’t simply collapse in a heap of self-pity, stop writing, or commit suicide. He continued on and was very helpful to one or two other friends in the same predicament. He has been criticized for refusing to make a public statement about his diagnosis, which would have been received by other people with HIV as a form of support. But Hammer sees his decision as a considerate gesture toward his elderly mother, and also toward the partner attached to him during those final years. The acting career of this young man, though he was HIV-negative, might have been hindered had there been any doubts concerning his own health. It should be noted, too, that public figures in Merrill’s generation always tried to avoid the stigma associated with medical problems, above all sexually transmitted illness. Enlightened individuals might not regard it as morally compromising, but the general public was a different proposition. Only Merrill’s closest associates were told, and then sworn to secrecy. He died in 1995, a month short of his 69th birthday. I can’t help wondering if content from his poem “The Broken Home” occurred to him after admission to that final hospital in Arizona. Early lines of the poem had, apropos of his father Charles E. Merrill, alluded to the proverb, “Time is money” and then summed up the latter’s death this way:

We’d felt him warming up for a green bride.

He could afford it. He was “in his prime”

At three score ten. But money was not time.

Nor was it a guarantee of long life for James Merrill himself. There’s every chance that this poem and many others of his will continue to be valued as long as we have a well-educated reading public. Yet, as his Ouija epic warned, there are major threats to our planet and the culture it shelters. For us, too, time is running out. •

Photos by Judith Moffett via Wikimedia Commons (1 | 2) (Creative Commons).