Picture it — the year is 1998. You are 16. You’ve just bought your first car, a gold/bronze 1986 Honda Accord EX. The A/C is broken; the power steering doesn’t work, the result of a permanent, occult leak in steering fluid, reminiscent of Lyle’s ‘23 Farmall tractor in James Galvin’s The Meadow (“It leaks exactly one coffee can of water a day whether you drive it or not.”). Its saving grace, the stereo — the previous owner had the good sense to upgrade to a Kenwood deck with a six-CD changer. And it’s yours, all yours, paid for in cash with a summer’s worth of earnings from your first “real job”: working as a research assistant in a neuroimaging lab at the local university, manually tracing cerebral gyri on thousands of MRI images in a dark basement.

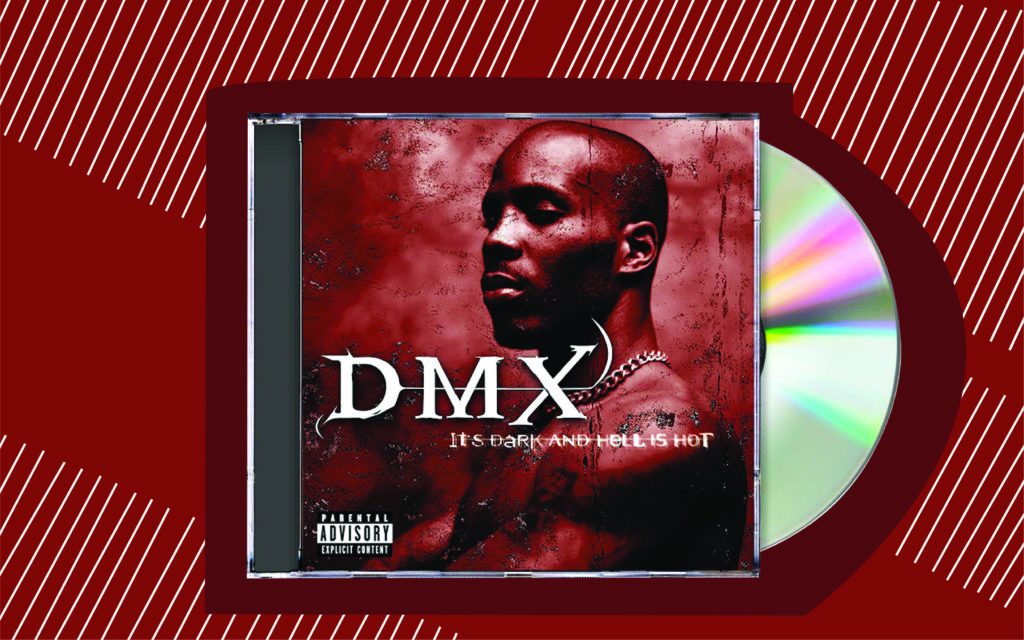

What’s the first album you buy, the one you’ll make sure to play with all the windows down, pulled up at every stoplight? That summer, the summer of 1998, of hormones and adolescent sturm und drang and taking surreptitious sips from your friend’s dad’s bottle of blueberry schnapps, the summer of France’s 3-nil World Cup defeat of Brazil, of embassy bombings in Africa, the intimations of a dark preamble to a post-9/11 world from which we’d never leave, there was only one correct answer: DMX’s It’s Dark and Hell is Hot.

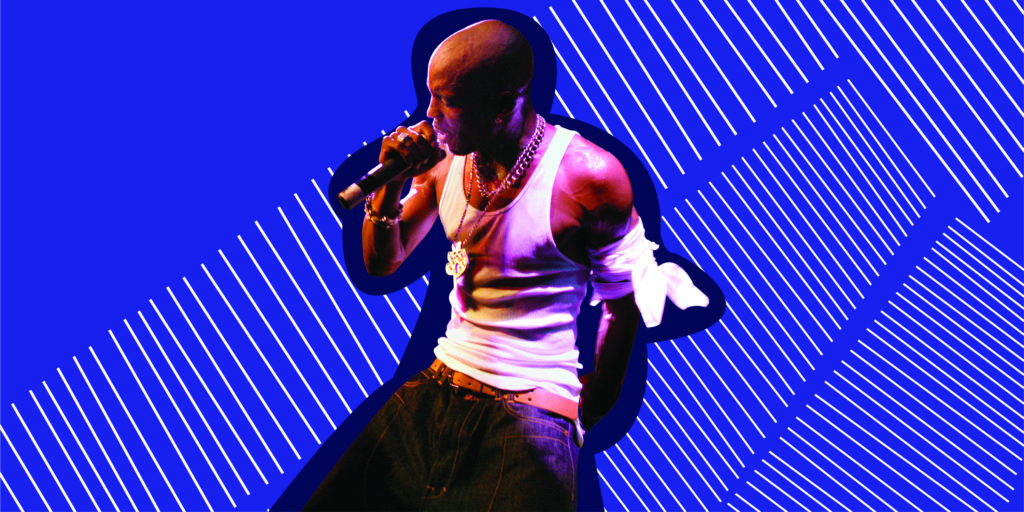

That summer, it was everywhere, pouring out of every storefront, pumped into every mall Foot Locker. DMX, X, Dark Man X, née Earl Simmons, provided the de facto soundtrack to those languid days, with his drill sergeant bars, his characteristic voice (words fail, but I’ll attempt a description: brown liquor filtered through a handful of gravel in a sweat-stained bandana — how’s that?), and, especially, his staccato, feral ad-libs — every X track containing a song-within-a-song of barks, growls, and grunts (has anyone every isolated the ad-libbed vocals off of a DMX track? I’d listen to the hell out of that).

Highlights from the tracklist: “The Ruff Ryderz Anthem”: a banger, top to bottom, an object lesson in what can be achieved with only a pentatonic scale and a metronome stuck at 91 bpm. “Get At Me Dog,” the single, which licensed us, for the rest of the summer, to ask aloud at any moment where our dogs were at. These were not 50 Cent’s champagne-drenched, feel-good club anthems. These were something else. Listening to X, even a song like “How’s It Goin Down,” the requisite rap album ballad with a de rigeur ’70s funk sample, one got the sense that, had he not been in the studio; had he been, say, a mechanic or the guy that cut your hair, he would have been just as apt to tell you about his romantic entanglements in exactly the same cadence, with exactly the same sandpaper-like timbre.

And then there were the music videos. For a scrawny kid who, in high school, managed to opt out of P.E. in order to stack his schedule with AP classes, they were a revelation, at once inscrutable and alluring: a pastiche of dirt bikes, women, pit bulls, chains, six-pack abs, and scowls. When X, the pack leader, shirtless and in a front-knotted bandana, stood on top of a bombed-out school bus and spat into the camera “all I know is pain,” for a brief moment, you, while watching BET’s 106th and Park in your parents’ living room, could convince yourself that you, too, knew that pain; that the metaphysical chasm between suburban North Carolina, with all of its bourgeois comforts (which you’d never left), and Yonkers, New York (a place you’d never heard of) maybe wasn’t that vast.

It is here, customarily, where the critic will talk about the “impact” that a particular album has had on his evolution as a moral and political creature; how, even decades later, in his darkest moments, he’ll cue up said album as a sort of balm for the troubled soul. I will adopt no such pretenses. I am a practicing doctor. I still live in North Carolina, and I still drive a Honda (now a hybrid). My day-to-day concerns are, somehow, even more quotidian than they were when I was a sheltered teenager: Paw Patrol and fruit snacks. If DMX had any immediate relevance for me at the age of 16 — realistically, he has even less now. Music, in other words, has taught me a lot of things over the years, but I can’t say, with any reasonable claim to honesty, that I’ve internalized any “lessons” from X’s verses.

And the fact is, over the years, as my music tastes changed (I hesitate to use the word “evolved,” especially considering my now-regrettable punk phase), X himself became relegated to the sidelines of pop-cultural prominence. His flow — often criticized as simplistic, more bark than bite — began to stand out even more, especially compared to, say, the lexical legerdemain of someone like Eminem or the melodic, intoxicated mumblecore of Future. It wouldn’t be long before he would enter the realm of caricature, and, eventually, cultural amnesia. When his name came up (less and less often, it seemed), it wasn’t because of his music. There was the time when he didn’t know who Barack Obama was (“Where he from, Africa?”); or when he made headlines for impersonating a federal agent (“I make moves. I make people disappear.”).

Why, then, the immense outpouring of grief, the countless essay tributes (this one being no exception)? I have to think it’s something more than mere millennial nostalgia for the halcyon days of MTV and TRL. One idea: As rap became a genre increasingly comfortable with willful artifice (see: Rick Ross’ transition from correctional officer to faux cocaine kingpin), DMX, somehow, through it all, remained guileless. A resurfaced interview with his producer, Dame Grease, reveals that DMX, when he wasn’t in the studio, listened to disco. He wore his heart on his sleeve. A mere 3214 unique words per first 35,000 lyrics (placing him dead last in terms of verbal complexity among hip-hop artists, a fact which garnered no small amount of scoffing from internet commentators in the early 2010s) belied a raw honesty that, as postmodernity hurtled along and everything became an exhausting competition in ironic detachment, made him easy to parody — or, worse yet, overlook altogether.

Lester Spence, in his book Knocking the Hustle: Against the Neoliberal Turn in Black Politics, writes about the rise of entrepreneurial, self-made “hustle” culture among young black men, celebrated in the lyrics of artists like Jay-Z (“I’m not a businessman, I’m a business, man”). Excluded from the labor market due to structural shifts in the global economy, the lumpen victims of over-policing, and welfare retrenchment, this is a demographic that has seen declining prospects for decades. And in hip-hop, it seems, the cultural response has often taken the form of hyperbolic consumption (consider Jay-Z’s references to copping a Basquiat) or paeans to the drug trade (à la Freddie Gibbs).

But with X, this anomie always seemed to manifest as something else: he wasn’t bragging about investing in Picassos or cooking white in the trap; his struggles resided in the psychological depths plumbed by Nietzsche, not in the economic determinism of Marx. Consider the song “Slippin’,” off of his sophomore album Flesh Of My Flesh, Blood of My Blood, released, remarkably, the very same year as his debut. “Wasn’t long before I hit rock bottom,” he raps plaintively, “n****s talkin’ sh*t, like, ‘Damn, look how that rock got him’.” This sort of naked, confessional hip-hop placed him, in 1998, squarely at odds with the bombastic wordplay of his contemporaries. But now? In an age of widening inequality, a viral pandemic floating atop a submerged epidemic of loneliness, a country racked by “deaths of despair” — DMX seems less like an anachronism and more like an oracle, right at home alongside someone like the late rapper Mac Miller, whose highly visible struggles with addiction were the source material for some of the best hip-hop in recent memory. Looking back, I can’t help but feel that, more than two decades ago, X knew something that the rest of us didn’t.

When the news broke that DMX had died, I, like a lot of people, cued up his entire discography on Spotify and, after having not listened to him in ages, played it on repeat. My wife was patient, if not completely understanding; my son was, more than anything else, irritated that we weren’t listening to Raffi. But somehow, it didn’t feel like enough. So while writing this essay, I went back to my parent’s house and fished out my old nylon CD binders, which my mom, to her great credit, kept after all these years. Thumbing through the polypropylene pages, past the usual suspects in alphabetical order — Atmosphere, Biggie — I noticed that the sleeve that would have contained DMX’s first album was empty. I felt a twinge of sadness, though I suspect I know where it ended up: still in its customary position in slot one of the Accord’s CD players. The car, which stopped running only a few months after I bought it, has long since been scrapped for parts. I can only hope X’s album made it out alive. •