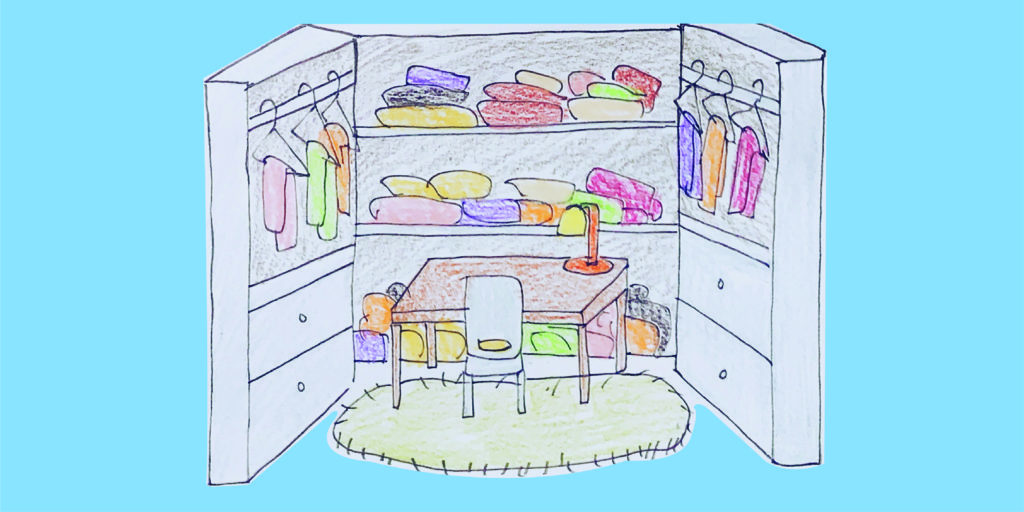

Have you heard of the new blend word “cloffice”? It’s a room that you create by turning a large closet into an office, usually in a house that doesn’t have such a room for solitary work. If your work is writing, I suggest that you keep some of the clothes hanging in there when you “clofficize” the space. Because if you ever run up against writer’s block, you could follow the example of the many authors who have been inspired to write stories about clothing — both their own and others’.

Just think of the clothing classics, like The Overcoat, The Woman in White, and The Illiad. (You think that epic is about the Trojan War? Sure, but remember that it concludes with a fight to the death between Achilles and Hector, who both wore a suit of armor fashioned by the god Hephaestus.) Yet as one who delights in peeling back the layers of facades, fads and vanity in fashion to reveal its comedy, I’m drawn to the funny stories in this sartorial genre.

In the first such story that most of us come across, “The Emperor’s New Clothes, ” by Hans Christian Anderson, the eponymous clothes don’t even exist. If it is read to us before we are literate, we can still giggle at the illustrations of an unsightly, naked body. And the emperor’s subjects also laugh as he parades in his birthday suit. But the emperor could have the last laugh: what if he had been in cahoots with the crooked weavers and had them make an invisible outfit so he could finally indulge his long-repressed exhibitionism?

Close in time to Anderson’s era, a poet and philosopher both wrote amusing appreciations of their dressing gowns. In “Dressing Gown Farewell,” Russian poet Piotr Andreevich Viazemsky fondly recalls how the garment transformed him:

So I, removing worldly livery

Together with the yoke of vanity,

Revived when I put on my dressing gown,

And reconciled once again with my abandoned home. |

When I was with you, vanity avoided me

And dreams and reveries caressed me.

In “Regrets on Parting with My Old Dressing Gown,” Denis Diderot compares his old, discarded gown with his new one: “Why didn’t I keep it it? It was used to me and I was used to it. It moulded all the folds of my body without inhibiting it; I was picturesque and handsome. The other one is stiff, and starchy, makes me look stodgy. There was no need to which its kindness didn’t loan itself . . . If a book was covered in dust, one of its panels was there to wipe it off. If thickened ink refused to flow in my quill, it presented its flank.”

I found these remembrances of dressing gowns past on the website of the journal Vestoj “The platform for critical thinking about fashion.” I didn’t expect to find a lot of laughs in a publication named for the Esperanto word for “clothing” and dedicated to a 10-point “Manifesto” (Number 3 begins “Fashion must always be taken seriously.”) Yet along with the quaintly witty dressing-gown pieces there was also a more broadly funny one by a famous artist. An excerpt from The Philosophy of Andy Warhol From A to B and Back Again, is about the artist shopping for underwear with a friend. “This saleslady was pleasantly plump in her neat navy-blue shirtwaist dress with a red-and-white scarf tied around her double chin,” Warhol writes. “She had a nice smile and eyeglasses with rhinestones sprayed around the frames. She looked like the type you could feel comfortable talking about underwear with.”

Worn Stories, a book by Emily Spivack in which she collected memories from over 60 “cultural figures and talented storytellers” about items of clothing that have been significant to them, sounds like a book that would be right up my alley. So after I read it, I wondered why I wasn’t really taken with it. To be honest, I probably was miffed because I didn’t think of writing such a book before Spivack did. Yet I also missed the humor in clothing that I’ve been writing about here. That’s why I wrote a speaking part for fashion entrepreneur Andy Spade’s old leather jacket.

Spade tells us that he bought the jacket, stiff and dusty, at a flea market, where he learned it had been hanging in an attic for 15 years. In fact, it “bleeds” green dust every time Spade wears it. But he doesn’t mind. He likes clothes with real “history,” while he hates new, “fake old” clothes splattered with paint or acid washed. Even the musty smell acquired in the attic appeals to Spade, who calls it “my cologne.” That’s all well and good for him, but consider the jacket’s point of view. I imagine its story about hanging for so long in the attic would sound something like the plaintive, stream-of-consciousness tales from one of Samuel Beckett’s characters:

Find myself in a dark room with other jackets other coats none as old and wretched as I. Little clump of green dust below me the only proof of my existence. Ah, for the old times with my first owner before the stiffness set in. Manly leather smell on me then not this musty stench making passers-by hold their noses can’t blame them. The great outdoorsman (Ha!) dragging me along through no end of ungodly weather. Rain the ruination of my supple leather. Then he was gone where to I wonder probably the void that awaits us all.

If I would have been famous enough for Spivack to ask me to contribute a story to her collection, I would have offered her one about a jacket of mine that’s both cushy and mythical: what I call the Golden Fleece. It’s made of the soft, plush fleece of that color, with a thick pile that you can sink your hands into. Several women have done exactly that; even total strangers. But when I wore it while visiting my sister, Diane, in Davis, California, she had to tell me its “Nanook of the North” look was out of place in that mild, Golden State climate. I’ll show her this, me, the younger brother, thought. “Just watch,” I told her as we stood on the corner of one of the main streets downtown. “I bet that as we walk down the street, at least one woman will ask to touch it.” When one woman did pop the question, I smiled at my sister and hurled myself at the hands-on woman so she could rub my arm. She must have thought I had just come out of solitary confinement.

I always assumed that any story about one’s clothes, funny or serious, would be more interesting to the teller than the listener. Yet a full-length play comprised of five seated women talking about the memories triggered by certain outfits from their past is absorbing from beginning to end. That’s probably because “Love, Loss and What I Wore” was written by the always entertaining sisters Nora and Delia Ephron, based on a book of the same title by Ilene Beckerman, with the addition of stories from the Ephrons’ friends. The professional actors relating the stories helped, too.

The mix of comic and poignant stories helped the play move along briskly. We hear about a shirt that feels and looks so good that “you have to make yourself not wear it” every day. How a woman found relief from the foot pain caused by wearing heels when she discovered Birkenstock sandals and outfits that went with them, only to have her husband say, “You look like a troll from Middle Earth.” And strong opinions like, “I just want to say when you start wearing Eileen Fischer, you might as well say, ‘I give up.’” We also empathize with the woman who recalls the shock of seeing her stepmother wear the exact same robe that her own mother wore years ago, and another one who is thrilled by the gift of a white, lacy bra when she had breast reconstructive surgery after a double mastectomy. If typical men supplied the stories for “Love, Loss and What I Wore,” the play would be pretty boring. Think about it: probably the only outfits they could remember would be the uniforms they wore while playing sports on a team. Then the book could be called “Won, Lost and What I Wore.”

But “Love, Loss and What I Wore” resonated with me because I, too, can recall what I was wearing on certain days — both good and bad ones. In fact, just looking into my closet and dresser drawers is like a walk down memory lane. So the only way I can wear an item that triggers bad memories is to wear it with one that evokes good memories, which must be vivid enough to override the ones I’d rather forget. Take these examples of competing clothing:

| Bad Memory Item | Dominant Good Memory Item |

| Multi-color, striped t-shirt worn when I had a heart attack | Stretchy tan shorts worn at many music concerts and family hikes |

| Navy blue blazer worn to several interviews for jobs I didn’t get | Curved, pink-and-white tie, tailor-made in the shape of one section of the blueprint for the MASS MoCA Museum, where I purchased it. |

| Purple, hooded raincoat worn during storm that flooded my Saab | Classic waterproof fisherman’s rain hat worn to fireworks on the 4th of July when rain was threatening. |

Speaking of bad memories, what may be the most damning words ever addressed to an item of clothing come from a writer we don’t usually associate with clothing: Herman Melville. His early, autobiographical novel, White-Jacket, is titled after a white jacket that the narrator wore at sea and the nickname his shipmates gave him. The eponymous jacket was originally a white duck shirt, but its owner needed warmer protection from the “boisterous weather” the ship would encounter when rounding Cape Horn. So White-Jacket “bedarned and bequilted” the inside of his jacket with old socks and scraps of clothing. Yet it was hardly waterproof, so the rain made it soaked and heavy — an unsafe burden when he was “sent up” the ropes to tend to the sails.

But the white jacket proved to expose our hero to more dangers than getting wet. One night when he was reclining peacefully among the canvases in the main top, the sailors on the deck below took him for a ghost and, to check its “corporality,” lowered the halyard, sending White-Jacket on a frightful descent to the deck.

On another night when White-Jacket was high aloft, this time threading new ropes through the sails’ blocks, the ship took a sudden dive and plunged him into the sea. He tried to swim, but his heavy, wet jacket prevented him from doing so. Since he couldn’t untie its binding strings in his precarious position, he fished out his knife and slashed the jacket to free himself.

“‘Sink! sink! oh shroud! thought I; sink forever! accursed jacket thou art!’’’ White-Jacket shouted. Then thinking the offending jacket was a white shark, his shipmates on deck made sure the garment followed White-Jacket’s command by striking the white garment with their harpoons.

Perhaps the best-known outfit of any American writer was also white: Mark Twain’s suit. I don’t know if he ever wrote about the outfit, but on his last visit to Washington, D. C. he made an outlandish comment about it, according to a Chicago Tribune from 1906. When asked why he was wearing the summery suit on that cold December day, he said, “This is not a suit; it is a uniform. It is the uniform of the American Association of Purity and Perfection, of which I am President, Secretary, and Treasurer, and the only man in the United States eligible for membership.”

Would Twain’s character Huckleberry Finn call that remark a “stretcher” or a “whopper”? Or was Twain mocking the hyperbole that seems to be endemic to Washington? •