There are two Gettysburgs. One is the battlefield, today preserved as the Gettysburg National Military Park. More than a million visitors come here each year to see the fields and forests where Union and Confederate troops met 150 years ago this July 1. Many will come this summer to celebrate the anniversary of the pivotal battle, the deadliest in North American history.

I first experienced this Gettysburg last year, when I took my dad — a budding Civil War buff — there for Father’s Day. We started at the new visitors center, where we watched “A New Birth of Freedom,” narrated by Morgan Freeman. We looked at the famous Gettysburg Cyclorama: a 130-year old, 360-degree painting that depicts Pickett’s Charge. Then we bought a CD guide in the gift shop and drove the 24-mile auto tour, zigging and zagging across the park as we followed the story of those three important days in the Civil War.

The other Gettysburg is the town that gave the battle its name. I explored this Gettysburg just last month with my partner — a fellow fan of all the stuff surrounding notable places and important things. Rob and I like solemnity in small doses, but we have infinite enthusiasm for its opposite. For us, any town with a Victorian photography studio, Civil War wax museum, multiple ghost tours, a fireworks superstore, and the General Pickett’s All-You-Can-Eat Buffet is a town worth exploring.

The explicit and often goofy commercialism of Gettysburg offers a stark contrast to the sobriety of Gettysburg the battlefield. Visitors who spend enough time in both may even pick up on a tension between the two. On the surface, the National Park wants to honor and interpret the battle, whereas the town just wants to make a buck off of it.

The work of the National Park Service over the past decade seems to reinforce this distinction. Much of the landscape here has changed in the years since the battle. Farms turned into forests, and invasive species appeared. Trees and fences disappeared. But in 2000, the Service began trying to restore the site to its 1863 appearance. This was not simply an aesthetic decision: Both the natural landscape and man-made elements on it influenced the battle. Removing “non-historic” trees and discovering long-lost farm roads would help the park and its visitors understand how generals organized and moved their troops. Restoring small features — such as fences and orchards — would offer insight into the experiences of small units and individual soldiers, for whom a split rail fence could mean the difference between life and death.

The Park Service removed selected man-made features along with the non-historic trees. Most famously, it demolished the former home of the Cyclorama: a modernist structure designed by architect Richard Neutra for the 100th anniversary of the battle. That building was just one of many such structures to appear in National Parks around that time as part of a federally funded construction program known as Mission 66. As part of this program, the government built modern visitors centers at Yellowstone, Zion, Grand Teton, and Mount Rushmore, among other sites.

When it opened in 1962, Neutra’s Cyclorama Center was a celebration. But by the 1990s, the National Park Service thought it an eyesore. Preservationists fought to save the building but the Service triumphed. It demolished the structure earlier this year. The Pittsburgh Post-Gazette covered the event, and interviewed a witness on-site to watch the process. “I’m not happy about this demolition at all. I was against it from the beginning,” he told the newspaper. For him, the Park was focusing on the wrong eyesores. “I understand that federal officials want to restore the battlefield,” he said, “but then why don’t they get rid of the McDonald’s fast-food place, and the Friendly’s, and the Kentucky Fried Chicken?”

A park volunteer, however, captured most people’s feelings toward the Cyclorama Center. “It’s a nice piece of 1960s pop art,” she said, “but it doesn’t belong on a battlefield.”

Neither, apparently, did the Home Sweet Home Motel. The one-story, mid-century motel was built on the site where the left flank of Pickett’s Charge crossed on July 3, 1863. The Park Service acquired and demolished the motel in 2003, but nobody shed a tear. No one found in the Home Sweet Home the kind of historical value that they did in the Cyclorama Center. In its magazine, The Sentinel, the Park uses before-and-after shots of the site as a demonstration of the Park’s changes, which are framed here as progress.

I like the Home Sweet Home Motel. In describing Gettysburg’s transformations, a reporter for the Associated Press suggested the motel “just didn’t provide the right feel.” But I’m drawn to the feel the Home Sweet Home Motel suggests. I like its neon “vacancy” sign, and thinking about all the summer family vacations it saw and all the Civil War-buff fathers it hosted. I understand that it wasn’t part of the 1863 landscape, but then again, neither was the asphalt road that the Park Service keeps there.

•

Not everyone shares our enthusiasm for Gettysburg the town. This spring, in Smithsonian magazine, historian Tony Horwitz asked, “Has Gettysburg kicked its kitsch factor?” My question: Why does it have to?

Horwitz finds the new Gettysburg offers a “richer” experience than the one he had as a boy visiting in the ’60s and ’70s. But he still finds it fun. He is especially taken with the number of costumed reenactors he finds in Gettysburg; these enthusiasts are so common, in fact, that they blend right in. “It’s the banality of weirdness,” a local history professor tells Horwitz.

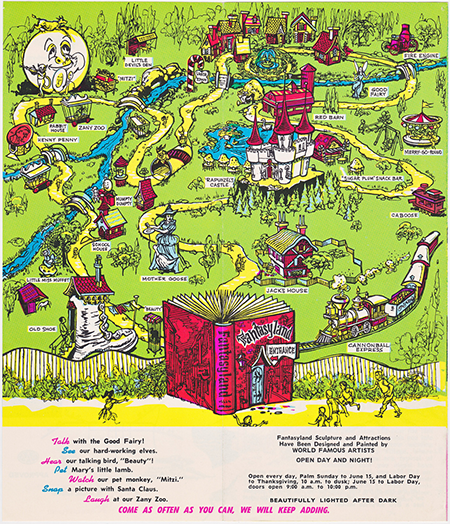

Gettysburg the Park has been trying to kick the kitsch factor of Gettysburg the town long before it developed a new master plan in 1999. In 1959, Kenneth and Thelma Dick opened a children’s amusement park named Fantasyland Storybook Park one mile south of Gettysburg’s downtown and close to the site of General Meade’s headquarters. Fantasyland offered attractions based on fairy tales, plus puppet theaters, live animal shows, and Indian “attacks.” The site boasted that presidents’ children and grandchildren made repeated visits; it described itself as “truly a ‘must’ for discerning families.”

The Park Service disagreed. It would decide what discerning families truly must see and experience at Gettysburg. In 1974, it bought Fantasyland but allowed the Dicks to continue operating the site. Fantasyland finally closed in 1980. The Park Service also allowed the Dicks to stay in the house they owned there. Thelma did until last year, when she died at 93 . Then the Park Service demolished the house.

•

Before we left Gettysburg, Rob and I parked by the site of the old Cyclorama Center. We climbed to the hill where it once stood. Nearby, Union troops pushed back against the 12,000-troops in Pickett’s Charge on July 3, 1863 — the climax of the battle. The Cyclorama Center had been completely demolished. Wire fencing with “AREA CLOSED” signs surrounded the site. A mixture of straw and young grass covered the area. To the southwest, fields spread down from this hilltop, and it was indeed easy to imagine both the battle that was fought there and the carnage it left behind.

I don’t doubt that the National Park Service’s recent work at Gettysburg helps visitors envision the landscape as it looked in 1863. I don’t question that this a certain kind of educational value. But I do reject the implied notion that there is one best way to remember and interpret the past. At Gettysburg, I wanted to push back against the idea that there is any such thing as a “right feeling” or an objective idea of what “belongs.” Fantasyland, the Home Sweet Home Motel, and the Cyclorama Center have a history, too: that of the Battle of Gettysburg’s centennial, when the Park and the town prepared for the visitors who came to celebrate the 100th anniversary.

Standing by the fence at the site of the former Cyclorama Center on the eve of Gettysburg’s 150th anniversary, I turned to the west and saw the Kentucky Fried Chicken that the witness for the Post-Gazette derided in his defense of the Neutra building. This was possibly the most curious spot in all of Gettysburg, a place from which a visitor could see both Gettysburgs’ past, present, and future. He could see here signs of the country’s debates over how it will remember itself, and the stark reminders of what, in large part, it actually is — the weirdness of banality, I suppose.

Of course not everyone will have this experience. Soon the grass will grow in, the fence will come down, and only the parking lot will remain. Visitors will drive to this site, climb the paved trail to the top of the hill, and try to ignore the KFC on their right as they imagine what this place looked like in 1863. • 28 June 2013