Maggie Haberman, the Pulitzer Prize-winning New York Times political reporter, CNN commentator, and now biographer of former president Donald Trump, is one of those figures who inspire anger and hatred from different people on different sides of the political spectrum.

While Haberman has been an active journalist since the mid-1990s, it was her Trump-era work that made her a divisive figure. She’s been a CNN contributor since 2014 and joined the Times after a five-year stint at Politico in early 2015. She was first hired as a presidential campaign correspondent months before Trump announced he was running.

To the right, and per the social media musings of Trump himself, Haberman is merely one of the most prominent of the evil, biased mainstream media who are out to get Trump at every turn. “Third-rate reporter” is a favorite Trump insult.

But to many on the left, Haberman is something very different. She is an “access journalist,” a “Trump whisperer,” and an unquestioning stenographer and shill for the 45th president.

In even nastier terms, she’s even been compared to Leni Riefenstahl, the notorious Nazi propagandist filmmaker who filmed Adolf Hitler as a golden god in Triumph of the Will. Those making this argument have occasionally gotten some ammo, such as the recent release of January 6 Committee testimony that a White House attorney had once reacted to an incoming phone call from the reporter by stating “Don’t worry, Maggie’s friendly to us.”

The former critique is unfair, albeit not particularly different from the usual MAGA world attitude towards the press. But the latter is even worse — nothing less than sustained character assassination. Those launching such charges, at best, show little understanding of how reporting works, and at worst, come from people who do not appear to have read the majority of Haberman’s reporting over the past eight years.

This debate has been revived with the late 2022 arrival of Haberman’s book Confidence Man: The Making of Donald Trump and the Breaking of America. The book, an exhaustive and illuminating examination of Trump’s life before, during, and after his presidency, is many things. But it is very much not the work of someone making the case that Donald Trump has ever been a good person or a good president.

•

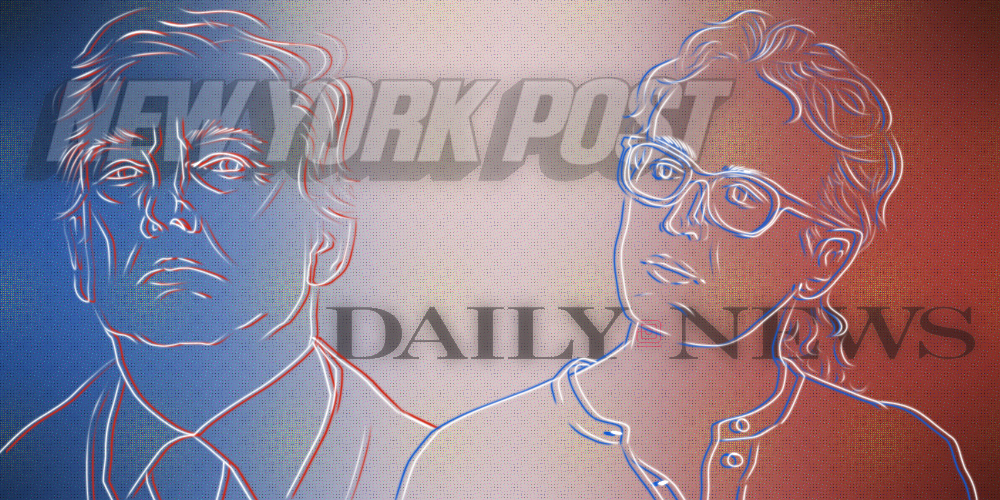

It is true that Maggie Haberman has a different relationship with Trump than most reporters, mostly because she has covered him for longer than most of them have. A graduate of the New York tabloid world who worked for both The New York Post and Daily News, Haberman sometimes covered Trump in his New York real estate mogul days, and later wrote some pieces for Politico about the possibility of Trump making a presidential run. Therefore, Trump takes Haberman’s calls and appears to crave the approval of the Times at large, and Haberman in particular, even if he goes on to trash both on social media as soon as her stories appear.

The result of this? Throughout his campaign and presidency, Trump frequently sat with Haberman, and sometimes other Times reporters at the same time, for lengthy, on-the-record interviews, which often made huge news. And more often than not, they made Trump look bad.

That’s because Haberman is clearly aware of a certain fact: If you’re a reporter, and you get Trump talking on the record for a long time, he’s going to say something incriminating.

•

Because of the dynamics of their relationship, as well as Haberman’s style — Trump once compared Haberman to his “psychiatrist” — it’s very possible that Trump’s people think Haberman is “friendly” or “fair.” When you read the transcripts of their interviews, they don’t feature Haberman interrupting or shouting “how dare you, sir!” That type of journalism isn’t her style.

But . . . that’s okay. If Maggie Haberman were the only political reporter in the world, or even the only one who had covered the Trump White House for The New York Times, the way she does things might be a problem. But she’s not.

The Times, in fact, employs a couple of dozen political reporters at any given time. Some ask questions in the White House briefing room. Others cover specific beats. Still others, at least during the Trump presidency, published faithful tick tocks of closed-door White House meetings, sometimes minutes after they took place, thanks to the prodigious leaking habits of just about every high-level aide who worked in the Trump White House.

Others rummage through documents. An entire Times team spent years trying to get a hold of Trump’s tax returns. They all have a part to play, and while the Times did not succeed in dragging Trump out of office early — as if that were the specific job description of a political reporter — they broke tons of stories during the Trump era, with Haberman leading the charge.

One gets the sense that a lot of anti-Trump media consumers like to imagine what they themselves would do if they had the opportunity to sit across from Donald Trump — a scenario that would likely involve yelling, name-calling, or an attempt to catch Trump in a lie or an inconsistency. Haberman doesn’t approach her reporting on Trump that way, which I believe causes such consumers to resent her.

Haberman has the bearing of an old-school reporter, one that’s far from the standard these days, especially at a time when traditional standards of journalistic objectivity are seriously fraying — a shift very much accelerated by the Trump era. Her prolific Twitter feed doesn’t call Trump “Cheeto” or “Drumpf.” She’s much more likely to include detached, reportorial observations about something Trump said or did — which, because Trump is Trump, are very often things that make Trump look very bad.

Haberman has continually broken stories about Trump, most of them negative. It wouldn’t be overstating things to say that Haberman has published damning information about Trump hundreds of times, quite possibly the most of any single media figure. Haberman was cited more times in the Mueller Report — the one that spent hundreds of pages laying out wrongdoing by Trump in the Russia affair — than any other journalist. This gets lost for a few reasons, both because most news consumers don’t pay attention to particular bylines, and also because many with strong opinions about Haberman are locked into their personal biases.

Longtime blogger Daniel Drezner wrote a long-running Twitter thread called “Toddler in Chief,” later adapted into a book of the same name, listing hundreds of examples of Trump acting like a small child, or his staffers describing him as such. He noted later that he had cited Haberman’s reporting frequently throughout the thread.

There’s a huge misunderstanding, especially among Haberman’s critics, of the overall relationship between Trump and the press. Yes, he called them names, stuck them in pens at rallies, and denounced them as the “enemy of the people.” But Trump also played the press at every turn and has been obsessed, for his entire public career, with how he comes across in the newspapers and on TV. This dynamic certainly helped Trump rise to the presidency, as he was given virtually unlimited free media in the 2016 race, while at the same time gaining votes from the right by ginning up anger at the press. Every time the media called Trump a liar or a unique threat, he could then turn around and accuse them of bias.

Post-Trump Republican candidates, like the odious Doug Mastriano, have misunderstood this, simply cutting off the press altogether and not gaining any of the advantages that Trump got from playing the media the way he did.

The book itself is exhaustively researched, painting a picture of Trump as a sleazy and dishonest businessman, a philanderer, and ultimately as a scandal-plagued president, representing reportorial insights gleaned by Haberman both over the years, and in new reporting for the book. Confidence Man details Trump’s various brushes with organized crime figures, with Russians, and with world-historical villains like Jeffrey Epstein and Roy Cohn.

Uncovered are numerous instances of Trump, at least, being racially insensitive, such as the episode when he appeared to confuse a racially diverse group of Congressional staffers with waiters, and when he implied he didn’t want to use the same White House toilet that Barack Obama had used (as it turns out, the Secret Service customarily installs a new toilet seat for each new president). Speaking of toilets, the book also uncovered that Trump may have flushed classified documents down one. And it’s clearly shown that Trump has not been known to treat the women in his life particularly well.

No, there’s not as much editorializing, as has been the case in many of the numerous books published in the last 18 months about the Trump years. But there are revelations, from the part about Trump flushing documents to Trump considering firing his daughter and son-in-law from the White House to Trump telling an aide that he would not leave the White House after the election. The book’s reporting included three separate sit-down interviews with Trump, and there’s also one page in which Haberman sent the ex-president a list of questions, and we’re treated to his handwritten responses.

Trump, naturally, denounced Confidence Man on Truth Social as “Another Fake book,” and alleged of Haberman that “she tells many made up stories, with zero fact-checking or confirmation by anyone who would know, like me.”

•

In addition to the bogus idea that Haberman is a shill for Trump, the other big critique directed at her is that she held news items for the book, as opposed to publishing them in the Times right away. But this, also, makes little sense.

First of all, Haberman did continue to break stories about Trump even while working on the book. The first revelations from the book — the part about Trump supposedly flushing documents — were revealed last February, eight months before the book was published. That’s just about the exact opposite of “holding it for the book.”

This was similar to the controversy, back in 2020, when Bob Woodward was found to have held a scoop about Trump’s COVID-19 comments for his book that fall, Rage, rather than immediately publish it months earlier. Those complaining about that always seem to be under the impression that one more revelation will mean the end of Trump, which has never, at any point in his political career, been the case.

That has never been especially true. All sorts of revelations over the years, from the Access Hollywood tape to the Mueller investigation to the circumstances of both impeachments to different aspects of Trump’s handling of COVID, have looked like the end of Trump’s time in politics. But while the cumulative effect of all those things almost certainly contributed to his defeat in 2020, no one Trump scandal has ever been a smoking gun- and even after all of that, he may very well become president again.

And perhaps more importantly, Haberman’s book was mostly reported after Trump left the office, so not “reporting it when it mattered” is less of a concern. If facts come to light two years after the end of Trump’s presidency, as opposed to after one year, what difference does it ultimately make?

•

If the purpose of a reporter is to get the story out of her subject by badgering them, yelling at them, or asking them point-blank why they’re such a terrible criminal, then Maggie Haberman is a failure. But that’s not what the job actually entails.

We know what it looks like when someone in the media is a shill for Donald Trump. Entire websites and books are dedicated to exactly that. But the “reporting” there looks absolutely nothing like Haberman’s. True Trump sycophants in the media like Sean Hannity, Kimberly Strassel, Sean Davis, or Mollie Hemingway wouldn’t even dream of writing a book whose title implies that Trump is a con man.

The other key difference is that Haberman’s reporting does not attempt to defend, excuse, or give a pass to Donald Trump.•