I approach this city with a spiraling movement, whose beginning and end I can’t determine. I conquer the town on foot, often on the move for so long that I feel nothing but muscle, bone, and heartbeat. Once I am past a certain stage, I am no longer thirsty, let alone hungry. Heat like this would normally slow me down, but my body reveals strengths that I didn’t know it had. I have a personalized map with spots marked on it wherever there is some association for me. These markings become gradually denser until they spread across the city like a spider’s web.

Everything feels different. And sounds different too. Early in the morning, I’m awoken from a deep sleep by the chanting. Some voices rumbling from the city’s belly are louder than others, and the singing comes from different directions, out of step. But perhaps each voice is aware of the others? I’m promptly wide awake, and rise to lean out of the window to hear them better, my eyes still closed. There are moments when I can’t tell if the ezan from the next-door mosque is echoing off the walls on my block or if I can hear the calls to prayers from other mosques.

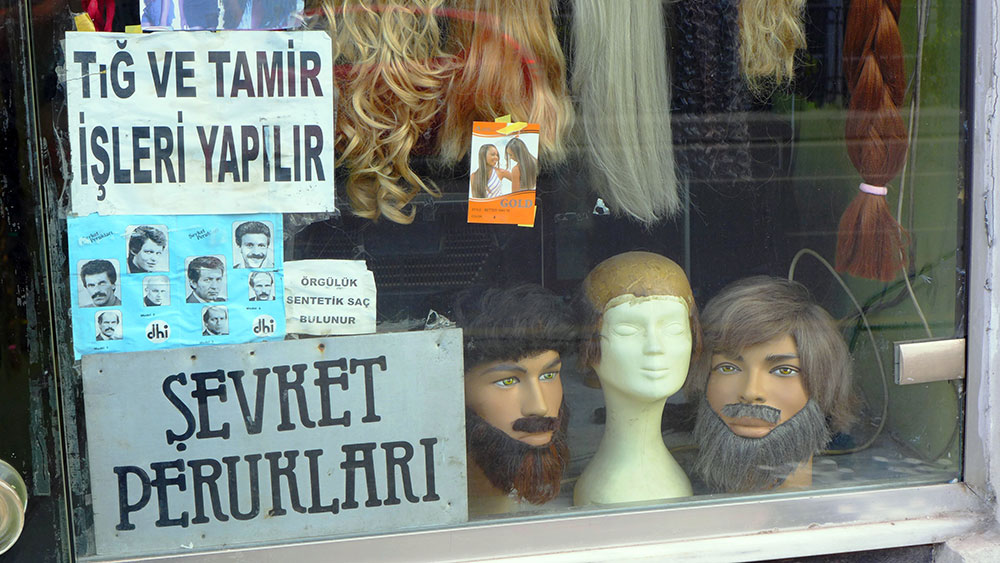

Before I came here I had all these images in my mind: mustachioed Mustafas, water-pipe smokers, traders in fezzes. Ottoman harems, shrouded women, characters with gold teeth who would try and lure you into dingy bars and hustle you. Pictures from Midnight Express starring Brad Davis as a tourist, arrested for attempting to smuggle drugs out of the country, who then undergoes an ordeal in prison. A guide to the city tried to make me believe that Turks are born holding scimitars.

From the roof of my apartment, I have a view across the all-but-ruined buildings in my neighborhood, the next-door mosque and the new Kasımpaşa football stadium. This is the district where President Erdoğan spent his teen years. The apartments in the neighboring buildings seem cut off from the outside world. A face rarely appears and I can seldom make out the movements of the people inside. I have been warned that this area isn’t safe, and when I come home, I walk in the middle of the street, not looking left or right.

Some say there is a particular kind of melancholy to be found in Istanbul, known as hüzün; but the city is so bustling that I can’t feel it, not by any stretch of the imagination. I watch workers slaving away on dusty construction sites, using their bare hands to carry piles of rubble, welding scraps of metal without protective masks, and exposing their face to flying sparks. When I see them scrambling about on precarious scaffolding, I feel as though I’ve been transported to a far-off, almost pre-industrial era. In the structural shell of a building, an elevator shaft gapes into an abyss and a handful of people plunge down it to their deaths. It’s reported on television; workers demand their rights. Then there are the garbage collectors, who can be spotted with handcarts even in the densest of traffic and who rake through containers with big hooks, looking for plastic parts and metal innards. Although it’s officially forbidden, this labor is said to put food on the table for thousands of families.

An inventory of small and great catastrophes: Out of the blue, a falling tree kills two women in a café. Someone steals the gravestones from Istanbul’s Karacaahmet cemetery, smuggles them out of the country, and puts them up for sale on a London website. A man throws his amputated leg in a dumpster and is later sued. The Turkish advisory board for television fines a private station more than 50,000 Turkish lira for broadcasting an episode of The Simpsons in which a Bible is burnt, God and the Devil are depicted in human form, and God serves the Devil coffee. The wall of the ruined building next door caves in without warning, making me first think there is an earthquake going on; it collapses in a cloud of dust and rubble that robs the neighbors on the ground floor of their view. Voices call out of nowhere, shop shutters rattle, mysterious shots ring out. On some nights, the cats cry like little babies. And the stray dogs bark incessantly. In the beginning, the noise overwhelms me, but soon it just figures in the background. Sometimes I can even detect a hidden beauty in it. It proves there is something going on, I tell myself, something that moves people.

I walk up and down Tarlabașı Bulvarı, along the sidewalks that are strangely out of sync with the buildings. I have to watch out not to step into shafts filled with water and garbage. Some of the front steps are in such derelict condition that I wonder how people even find the entrances to their buildings. In the small grocery shops you can find essentials round the clock. Soon the little nocturnal creatures come out: young boys getting high on yellow glue and the blind man who sells small, ultra-bright torches.

The people in my neighborhood don’t ask themselves who they are, where they belong, or how they should be. They know. And they’re indifferent to the great plans other people have laid. What counts is where and how you are right now. Whether you are happy. Herșey yolunda mı? Is everything all right? They’re not interested in me. Not even in the money I don’t have. They wouldn’t feel comfortable about taking anything from me anyway. They couldn’t square it with their pride. They’re poor, but they share food with their neighbors.

They believe that outside influences can threaten the order of things. A piece of cloth is tied to a branch to make a wish come true. Some people are said to have the nazar, or evil eye, when bad things happen. It is even powerful enough even to shatter the boncuk, a pretty blue glass amulet that hangs on doors for protection. The nazar embodies envy and evil wishes, but nothing happens to those who have it. They aren’t persecuted and their lives aren’t made difficult. It is accepted like a force of nature. However, people don’t like talking about it, or only in a whisper. Anything else is scandalous, even tempting fate.

There’s nobody here who associates any kind of story with my face. They don’t seem curious about me, but I don’t want to imply that they’re indifferent. Perhaps they simply don’t want to acquaint a stranger who, in their world and views, has no place — the gevur, or infidel. And they have every right to feel this. Yet they don’t dispute my place among them, and for that, I think highly of them.

The foreigners, the expats. We spot each other easily, especially when we’re new to the city. Acquaintances can be kindled by a passing comment. I soon notice that there is a kind of consensus on how we are supposed to regard this country. No, everything is not better in the West, it’s just different, and the people over there have their issues, I’m often tempted to answer. Some pet subjects of conversation are: all the things that don’t work, the supposedly ruthless taxi drivers, the same old stories about the chaos on the roads that you can easily avoid just by not traveling at certain times of day. Sometimes I just escape with the most barefaced lie.

Are there more crazy people here than in other big cities? The one-legged wheelchair guy, sunk in his monologues, claims his regular spot at the side of the road with a can of beer, and makes passers-by nervous with incomprehensible gestures, occasionally even throwing an empty can after them. The disheveled, ageless woman who clambers about on the crash barrier on the Bulvarı in the middle of heavy traffic — where’s she trying to get to? No matter how hard I try, I can’t work out the purpose of her exertions. One time, I watch a lame old man on crutches as he crosses a busy street at a red light, as if the traffic doesn’t exist, as if he is negotiating some dusty, barely used country road on the Anatolian plain. No one seems interested; no one gets upset. I don’t even think he’s aware of what’s going on around him. I wonder what book the long-legged Russian girl is reading in the Simit Saray coffee shop on Taksim Square, and what, apart from her lipstick, she is hiding in her black tote bag with the I hate Berlin insignia.

I want to behave respectfully and control outbursts of emotion, but I don’t always manage. How can those three men simply stand around doing nothing when an innocent skirmish between young Roma children turns into a quarrel with sharp sticks? This is too much for me. I step in, break them up, shouting: Yeterli! Enough! At this moment, the smallest boy falls over, and is evidently so taken by surprise that he hardly defends himself when I quickly snatch both sticks from his hands. Abi, abi, big brother, he says in a whimper. The men just stay where they are, a gesture that seems to say that this foreigner is a fool to get involved. I walk on, still flustered by my uprush of feeling, and slip on a paving slab. I fall over onto my thigh with full force in a movement that strikes me as completely illogical. For a second, I struggle to regain my composure. Thank God nothing’s broken, I think, as the pain quickly rushes in. One of the men comes over and helps me up.

I start to worry less about myself. I become less self-conscious in a way that I’ve never experienced before. People warn me about the small clubs. You can easily end up with a hefty check for a bottle of champagne that you never ordered, and things can turn nasty if you refuse to pay. They can take you to the cash machine. Having said that, things are much more innocent than I’d imagined. Perhaps I took William Fitzpatrick’s Istanbul After Dark from 1970 a little too literally when he says he couldn’t get enough of its “bizarre thrills.” I give into the urge to have another vodka and tonic. In a Muslim city, of all places, I’ve developed a taste for stiff liquor. Alcohol is not sold in stores after 10 p.m., yet this country seems to have few problems with something that causes tens of thousands of deaths a year elsewhere. According to the statistics, much more than half the population has never touched a drop of alcohol. I don’t doubt that this is true.

I leave the bar and feel the warm, damp, windless night on my skin. All the humidity is rising up from the ground. There is a smell of urine, mold, and beer. On my way home, I pass through İstiklâl Caddesi, where at this time — 3 o’clock in the morning — a small group of demonstrators is clashing with the police. Tear gas is the last thing I was expecting. Later, there are no reports of this incident to be found anywhere in the press. The gaggle of international journalists has long moved on. As I reach my apartment, I hear the drummers for Ramadan coming around the corner; soon after, the calls for prayer begin. A few evenings later, I think I hear gunshots, which alarms me. But it turns out it was only the demonstrators letting off fireworks.

It is Ramadan. I want to surprise you, says Emrah, the Kurdish waiter from Hakkari in the far Southeast of the country, who works in a restaurant that I frequent every few weeks. Emrah is a featherweight, and fasting doesn’t come easily to him, but he would never dream of giving it up. His faith gives him strength and self-control. He suffers on these summer days because he’s forbidden to consume anything from sunrise to sunset, even a sip of water. Nevertheless, he’s content. We arrange to meet in front of a hotel near my apartment. What is he planning? We go to Eyüp. Nowhere around the mosque is a trace of devoutness to be felt. Quite the opposite. A fairground! A big wheel! Brightly cultured candy sticks twisted from a metal trough! Near the big mosques, which are adorned with bright letters on strings from minaret to minaret, the faithful have gathered. Visitors have their photos taken in Ottoman costumes. The celebrations go on until after midnight. We take a taxi back.

In strict secrecy, I subject myself to the stringent regime of the fast on its final days. I try hard to limit my movements to the absolute minimum, and renounce the tablets that promise to make my belly feel full during the day and suppress my gnawing hunger. I would only too gladly take part in a public iftar at sunset, where people break their fast together, but I feel bad because there are people who are dependent on this free food. I don’t want to pretend to be a Muslim; it’s about developing a feeling for what happens to me — if anything at all — and whether it creates a connection to the people who believe. I feel nothing.

In the meantime, Emrah has left Istanbul. At first he went to Erbil for a few days, the Kurdish region of Iraq, where he helped out in the pharmacy of a relative. Then he came back to Istanbul, already working on new plans. At our last chance meeting, he tells me that he wants to go Baku in Azerbaijan to do a study program as a sign-language interpreter. The last sign I receive from him is a friendship request on Facebook. He looks different in the photographs. He’s sporting a full beard and seems burlier. Under his profile photo, the location reads Kobane.

Istanbul lies between the Mediterranean and the Black Sea, but it is often just the seagulls that make you realize how close the ocean is. Why do they start up their awful screeching on early summer mornings and why do they fall quiet later on? Is it down to mysterious air movements, changes in temperature, or just competition with fellow birds? Supposedly there are people who have spent their whole lives here without ever having seen the sea. Life in the city is closely connected to the ocean, but you have to travel very far from the city even to be able to swim. Here and there on concrete promenades along the shore, daredevil boys and men fling themselves headfirst into the water, but even in the outlying areas of Istanbul, there is no safe access to the sea, not to mention the quality of the water.

I don’t care for more sophisticated cuisine. I like the roast chestnuts, grilled cobs of corn, and rice with chickpeas. I eat kokoreç, sheeps’ intestines filled with unidentifiable meat and spices, the aroma of which invariably fills me with curiosity and disgust as I rush past the metal skewers they are roasted on. And I sometimes starve myself on purpose so that I can gulp down the oysters filled with rice and a dash of lemon juice that are hawked at the roadside. I don’t feel like eating pork at all. I could even buy it here in one of the bigger supermarkets, or at a butcher’s that only has pork on offer. But when you haven’t eaten it for a long time, you lose the appetite for it.

Tourists mostly only stay for a few days. Many of them are Iranian, but most of them are from the Gulf States. The Arab man cuts a sporty figure despite being frequently portly; his wife is swathed in black and a niqab that only has slits for her eyes. A pair of sunglasses sometimes completes her anonymity. She raises her veil a little to sip on a straw. Families storm the restaurants and order around the waiters; back home, they are surrounded by people who are much like serfs. Next to them sit tourists in loose outfits that attract men’s eyes, but they get upset by the unwanted attention. These visitors haven’t understood that they should look away unless they want to invite contact. I am astonished when, at sunset, a group of Saudi tourists on the entrance steps to Gezi Park asks me where Mecca is. It takes me a few seconds to figure out. When I indicate it with my hand, they kneel down to pray.

The warmest weeks of the year arrive, and the temperatures remain constantly high. For all the filth that has accumulated on the streets — in the mountains of plastic bags stuffed to bursting with garbage, or the containers overflowing with milk cartons, chicken bones, and melon peel — the people are scrupulous about keeping their apartments clean. The heat is a drug; it brings me back down to my basic needs. The air burns into the soft tissues of my body. I wander down a street. A moped startles me. These little vehicles can appear out of nowhere at any moment. Not even the sidewalk is a haven.

A hot, dry wind arrives, known as the lodos. It blows from the southwest, from the Aegean and Marmara Sea, and it’s said to carry sand from the Sahara. In the afternoons most of all, it makes me feel as if the world has been turned upside down. Nothing seems to go right. The wind prevents any concentration. The landing stages for ships along the Bosporus are closed, and ferry services are stopped.

The mosquitoes here are smaller and more devious; their movements are swifter and more unpredictable. I only stand a chance of killing them when they’ve already sucked themselves full of blood. Sometimes I toss and turn for half the night in bed, only to have them win after all. On another evening, a whole swarm of large, black flies buzzes in through the window and circles the ceiling lamp as if governed by a faulty remote control. It’s an ambush. I manage to suck up many of them up with the vacuum cleaner. A few hours later, I find those who escaped the nozzle lying dead on the floor.

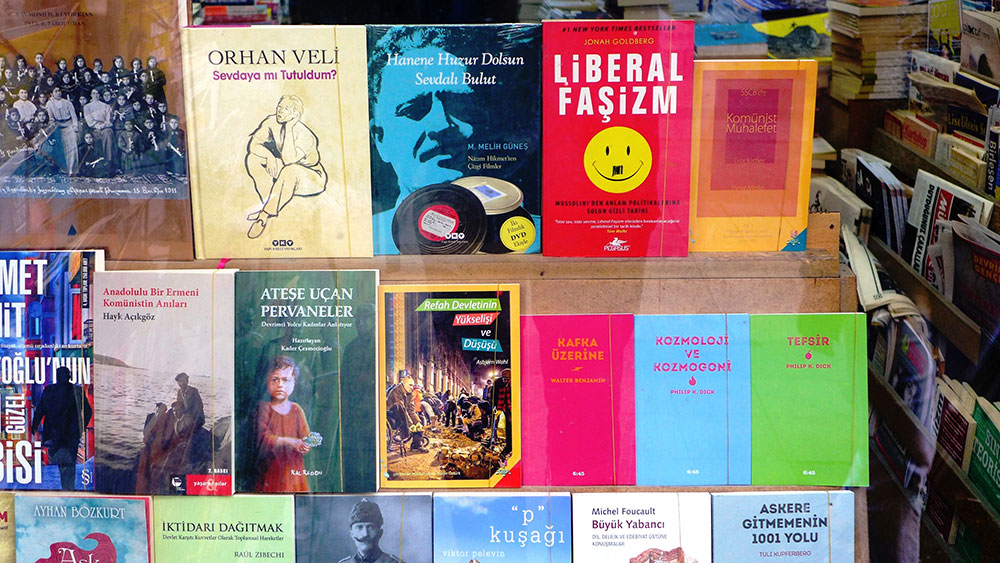

In one of the small second-hand bookshops, known as șahaf, I make a very special discovery among a jumble of photos and documents: city maps of Marseilles, Lisbon, and Rio de Janeiro. I wonder how many hands they have already gone through. Even after half a century, they are still in mint condition. I unfold them in front of me. How are the lives of the people in these ports connected to this city? Did a skipper collect them on his travels? Who did he meet? When did he return to Istanbul or how else did they come to be here? It appeals to me to live with the mystery of these maps for a couple of weeks before I put them back where I found them.

Everywhere I go I am surrounded by music. I especially like the kanun, or Oriental zither. I catch myself playing a tune in my head that I’ve picked up. Sometimes I wish I’d come here earlier, as I would have liked to see with my own eyes something of the Turkey of the past — the singer Barış Manço, for example, with his magical voice.

What to make of Harun Yahya, better known as Adnan Oktar, who is supposedly connected to the cemaat religious movement, and is considered a creationist? Oktar is around 60, sports a fastidiously trimmed beard and follows his own, very individual form of Muslim faith. Among his trigger words are Darwinism, the Holocaust, and Zionism. His female followers are not even obliged to wear headscarves. On a private TV channel, he appears with full-breasted, very blonde ladies doing obscure movements to electro beats. He calls them “pussies.”

When I meet people, they stay a while. To an eavesdropper, the simple conversations we have might sound banal. But for me, despite all our communication problems, they have an unusual significance and depth. They tell me about the places they have come from, and take me on a journey back to Anatolia:

A world of underground springs, where water is supplied by mountain snow and collected in large containers above the village, then channeled into the çesme (well), and never ceases to flow, in accordance with Muslim law. Where dogs are not allowed into the house because it is haram, and where they are given collars covered with spikes to protect them from wolves. Where people like cats but do not give them names. Where buğday (wheat), arpa (barley), mercimek (lentils), pancar (sugar beet), kavun (honey melon) and karpuz (watermelon) grow. Where fruit trees are planted across vast areas: kıraz (sweet cherry), vişne (sour cherry), kayısı (apricot), erik (plum), şeftalı (peach), elma (apple), armut (pear), dut (mulberry), muşmula (medlar), iğde (wild olive), and zerdali (wild apricot). Where people work in the summer and sleep in the winter. Where even the dead children in the cemetery belong to the family as if they were still alive.

Where entertainment mostly consists of visiting others and spending time together. Where the lives of men and women run on separate tracks, and where some, incredibly, still have reservations about sending girls to school. As distant as Istanbul might seem from this world, my two best Turkish friends bring me the best their country has to offer from home: honey and olive oil.

I like the people who live in my neighborhood. I feel drawn to the mixture of anonymity and intimacy in which we live alongside each other. There is a kind of commonality between us that I’ve never experienced before, and which I can’t quite describe. I take in their looks, gestures, dark eyes, bushy eyebrows and long lashes, the short, black, neatly trimmed hair on the backs of their necks, their features marked by hardship and exhaustion. Their coarse hands that stir tiny spoons in their tea glasses. Their low-set ears that often stick out. I hold back; I don’t ask questions. Bazı şeyler hakkında konuşulmaz — some things cannot be spoken about.

And there is a kind of acquaintance that I never knew existed before. After an inconspicuous beginning, it’s suddenly about all or nothing. No subtle gestures are required, no furtive, sidelong glances, no pretense. All at once, a pair of eyes fixes unwaveringly on mine. The person sitting across from me doesn’t ask himself if he’s crowding my space. All at once, I’m no longer simply the ağabey, the abi, the big brother; I’m the kanka, the kan kardeş, the blood brother. All at once, he is there and won’t leave my side. Do you live alone? he asks. Soon I am envious of my guest’s sound sleep, his peaceful breathing, and relaxed posture. Nothing, not a breath of air or a noise, disturbs him.

The men show me a different way of behaving in this world. With unshakable self-confidence, a lack of self-consciousness, pride. Only a man who has produced children counts. He’s a çoçuk sahibi, an owner of children. He must have done his military service. It’s a rite of passage. A man who has neither a wife nor children is to be pitied. Who will look after him when he’s old? they ask.

People here grasp situations intuitively, quickly form their conclusions, and once they’ve formed them, they don’t easily change their minds. They separate the real and the imaginary in a way that I’m not used to. You can’t tell when they’re selling you a white lie as a fact. On the other hand, they have an infallible sense of when you’re taking liberties with the truth. They’re impatient when they want to know something. They don’t forget easily but they don’t bear grudges either. “Let the snake that doesn’t bite you live for a thousand years,” they say.

One of my favorite places in the city is the Grand Hotel de Londres, the Büyük Londra Oteli. The name exudes an air of cosmopolitanism and luxury, chilled champagne and Agatha Christie, but in fact it’s just a shabby hotel where time has stood still for the past fifty years. The richly ornamented six-story façade that houses 52 bedrooms, designed by the Italian architect Guglielmo Semprini in historicist style, was once considered one of finest on Pera Hill, the European quarter of Constantinople. Birdcages, some of which contain live inmates, as well as a piano, chandeliers, heavy armchairs, gramophones, Ottoman sculptures, and silk curtains lend the lobby a strange appearance. An ageless woman sits there with an over-powdered face. Or is it just a mannequin? An entire spectrum of reds is on display, representing every shade: Egyptian red, sienna, a rather faded Bordeaux. It’s almost one hundred years since Ernest Hemingway alighted here and wrote about Turkish independence.

The friendly employee shows me the way. Best not to think too hard about a sign that says: “In case of earthquakes and fires, don’t use the elevator.” If there is an earthquake in Istanbul in the near future, and the voices predicting this have recently become shriller, you would certainly be better off sheltering someplace other than in these dilapidated walls. Once I get to the top, one of the three waiters is busy watering the abundant plant life. The view from the terrace on two levels, connected by a gently winding staircase, is breathtaking. Embedded in a niche in the wall is a cage with a pretty mynah bird. Sitting in the middle of this small paradise, I am strangely disconnected from the city’s goings-on. Spread before me is a view of the Golden Horn. Some think that the smog-covered city provides a rather ugly sight and recommend coming at sunset, all the more because the worst of the heat is then over.

For many months, my life has taken place within a radius of two kilometers. I have to move further afield until I reach the city limits, which are constantly expanding. Where there are people on endless motorways who are coming from someplace and heading someplace else. Where Istanbul has nothing to do with the city that Orhan Pamuk sermonizes in his books, the city that he once loved, and nowadays seems to almost despise. To Sultanbeyli, say, in the depths of the Asian side of the city. I am warned about this quarter, told I should keep away; allegedly there are more mosques with metal minarets there than schools.

In the late evening I return home and cannot believe my eyes: the light is on in my apartment and the door is wide open. Mustafa Bey, my landlord, is talking to two workmen. No apology for having simply broken into my apartment. I scan the room, checking to see if everything is in its place. There is a puddle on the floor. In the apartment above mine, a pipe has burst. The pipes are worth nothing these days, he grumbles. I have to put up with a smell of mold for the following week.

The cold days arrive late in the second half of November. The days are still light and even spread a touch of warmth, but as soon as the sun disappears, it turns abruptly cold. On Ömer Hayyam, I see three pigeons picking about for tiny, shriveled grapes in the withered branches of a vine. The market now sells the best pomegranates. One seller doesn’t just cry his wares, he sings. A truck stands nearby with a load of ripe, dark-yellow quinces. The market takes place on a street that continues deep into my neighborhood. It jolts me to see a leprous beggar woman. Her hands, when she reaches them up to me, are virtually no longer recognizable as such. On Taksim Square, a gigantic concrete expanse where puddles collect because the water drainage was forgotten when it was built at lightning speed, children squat on the floor, abandoned by their uncaring parents to inspire pity in passers-by. Some of them play on plastic harmonicas and beg for ekmek parası, or bread money. Prostitutes meander aimlessly across the square; their beauty has something angular about it, especially around the jaw. Sometimes they abandon all reserve and speak directly to a few of the men hurrying past in all directions, who nevertheless throw them brief, appraising looks. •

Translation from the German by Lucy Renner-Jones. Photos by the author.