Have you ever wondered what the secretaries are writing on their notepads? Have you ever seen the markings of the stenographers? Look over the reporter’s shoulder and you will see a strange, ancient-looking code. It could be Hebrew or Arabic or hieroglyphs. It could hold a secret message that only the transcribers know.

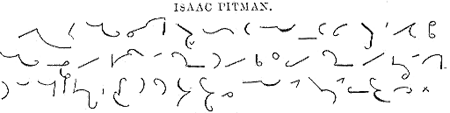

If the transcribers are speakers of the English language, they are likely writing in Pitman’s shorthand. Sir Isaac Pitman didn’t invent shorthand, but his system is the most widely used among English speakers today. Pitman published his first shorthand treatise in 1837, entitled Phonography, or Writing by Sound, being also a New and Natural System of Shorthand. Isaac Pitman spent every moment of 1837 perfecting his shorthand. Such are the obsessions of the single-minded. He didn’t even pause on the 20th of June, to celebrate the accession of Queen Victoria. “Not,” Isaac Pitman told his biographer, “that I loved Her Majesty less than other people, but that just at that time I loved Phonography more.”

Pitman called his shorthand “Phonography,” because his system was the literally the writing of sound. To create a system where words could be written exactly as they are pronounced — this was Pitman’s dream. Pitman’s shorthand consists of characters, with each character representing — not a word — but a sound in human speech. Emphasizing how words sound, how they are spoken, is the fundamental difference between writing with Pitman characters and writing with the Roman alphabet. For instance, the sound at the beginning of the word “cheese”, represented by the letters ‘c’ and ‘h’ in the Roman alphabet, is represented by / in shorthand. When you see the symbol, you don’t have to guess if it is pronounced ‘ch’ or ‘sh’ or ‘zh’ or ‘k’. It is exactly as the speaker said: /. Isaac Pitman thought that writing with the Roman alphabet was clumsy and inefficient, especially when it came to transcribing. Phonography linked writers directly to the spoken word. For this reason, some people call Pitman’s shorthand “the alphabet of nature”.

Pitman believed improving shorthand would be a great service to humanity. It wasn’t just a professional and educational tool but a timesaver for anyone who wrote. Pitman anticipated the day when shorthand would be “the common hand.” His motto was “time saved is life gained.” Phonography — which he sometimes called ‘Sound-hand’ — could have universal applications, since sound is universal even if specific sounds in languages aren’t. Pitman imagined a Bible “no larger than a watch,” to be “used for the discovery and regulation of man’s spiritual state with reference to eternity, as the pocket chronometer is for the discovery and regulation of time with reference to the present life.” Pitman invited all Englishmen to become Phonographers, and reap the rewards that would follow.

After the publication of his treatise, Isaac Pitman became a tireless promoter of Phonography. (Pitman was a bit of a social reformer. He was a great supporter of Postal Reform as well as, most significantly, Spelling Reform. He would also become first vice president of the Vegetarian Society). Pitman established a Phonetic Institute, arranged social gatherings of Phonographers, and lectured across Great Britain. He set up his own printing house and published The Phonographic Journal, written entirely in shorthand. He published shorthand transcriptions of the Psalms and Milton and Swedenborg’s Rules of Life — anything, Pitman said, could be transcribed into shorthand. Stenographers, secretaries, and newspaper reporters converted to Pitman’s method. A Phonographic Corresponding Society emerged. Pitman soon had hundreds and then thousands of enthusiastic disciples who sang the praises of shorthand. Eventually, Pitman’s shorthand would travel to the United States, and be used everywhere English was spoken. Pitman’s shorthand was not a system but a movement.

As any movement, shorthand had its opponents. The Reverend Edward Bickersteth denounced Pitman’s shorthand in a work called The Promised Glory. “Mesmerism, Phrenology, Phonography, Chartism, and Socialism,” he wrote, “are the stalking-horses behind which the most Satanic lies and the most absurd blasphemies are sent forth against the Word of God.” The Quaker poet Bernard Barton wrote a poem ridiculing Phonography, the Spelling Reform, and the “modern babblers” who advocated them. But these denouncements only increased Phonography’s popularity.

The famous reporter John Harland was a passionate defender of Pitman’s shorthand and wrote of its merits in the Guardian: “In these days of general acceleration, its universal use would be a great benefit to the civilized world… It is, in fact, a vivid picture and transcript of any and every language spoken on the earth; having as universal an application as the notation of musical signs, with this superiority — that it represents not only sounds like musical notation but,” wrote Harland, quoting the poet Thomas Gray, “sounds which are the images and signs of thoughts that breathe, and words that burn.” In the dreams of Phonographers, written language could be more like an instrument, recalling ancient days when all stories were songs.

The Preface to George Bernard Shaw’s Pygmalion is a long defense of phonetics. Actually, it is a defense of the phonetician himself. But why Shaw chose a phonetician to be the hero of his play was as curious to his first audience as it is today. We wonder, for instance: Why is Henry Higgins such a bastard? Why is he so obsessed with a matter so trifling as accents? In the play, the pettiness of his obsession is milked for comic value. The real justification for Higgins is to be found in the un-performed Preface, which Shaw wrote for his readers, rather than his audience:

The English have no respect for their language, and will not teach their children to speak it. They spell it so abominably that no man can teach himself what it sounds like. It is impossible for an Englishman to open his mouth without making some other Englishman hate or despise him…. The reformer England needs today is an energetic phonetic enthusiast: that is why I have made such a one the hero of a popular play…

Finally, and for the encouragement of people troubled with accents that cut them off from all high employment, I may add that the change wrought by Professor Higgins in the flower girl is neither impossible nor uncommon.

For Shaw — and Pitman — Victorian England was a degenerate Babel of accents, the result of an England fragmented by the modern Industrial Age. For the Henry Higgins-Shaw-Pitmans of England, the key to uniting English society was to be found inside its language. An England that could better communicate with itself would be a fairer, more rational, more enlightened society. “Remember,” Henry Higgins tells Eliza Doolittle, “that you are a human being with a soul and the divine gift of articulate speech: that your native language is the language of Shakespeare and Milton and The Bible; and don’t sit there crooning like a bilious pigeon.”

It’s no surprise that the phoneticians of 19th century England were almost all supporters of the contentious Spelling Reform movement, which sought to make English spelling more phonetic. Anyone who has ever tried to write in English knows how baffling English spelling can be. Pitman and his fellow language reformers thought English had the weirdest spelling system of any language using the Roman alphabet (the use of the Roman alphabet was itself considered weird but we’ll get to that soon). This was largely the result of conquests and international trade during the Renaissance. English spelling, they protested, took no account of the actual people who had to use the language, whether speaking it or writing it. Why, wrote Shaw, should we spell ‘debt’ with a silent ‘b’ just because this is how Julius Caesar liked to spell it?

Take an absurd word like ‘though’ (the reformers would say) which has six letters but only two sounds, not to mention all the over-lettered French words brought with the Norman invasions. “English orthography,” declared W.R. Evans in A Plea For Spelling Reform (published and edited by Pitman) “is utterly inconsistent, ineffective, misleading and irrational.” The reliance on the alphabet ‘borrowed’ from Roman conquerors had outlasted its usefulness. Why not write “though” as “tho?” “Debt” as “det?” Shorthand took this abbreviation even further. A symbol could replace ‘th’ for the sound made at the beginning of ‘the,’ and another for the ‘th’ sound that starts ‘thick.’ The pointless letter ‘C’ would need no replacing; it could be discarded altogether.

Written language so divorced from spoken sound, W.R. Evans wrote, has no vigor, no life. Writing becomes mechanical, even arbitrary. For Isaac Pitman, the consequences were grave. The word, as written, had started to lose its meaning.

The decision to translate Emmanuel Swedenborg’s Rules into shorthand was not a random choice. Isaac Pitman was a devout member of the controversial Swedenborgian New Church, and was fired from his teaching post because of it, two years after the publication of Phonography. The loss of his job and religious discrimination were the real impetus behind the establishment of Pitman’s independent publishing house and school.

Emmanuel Swedenborg had a good career as an all-around, 18th-century scientist/philosopher/inventor. That is, until one Easter weekend in 1744, when he started having visions. Swedenborg wrote many books about this spiritual awakening. He wrote that the Church was in man and not outside of him. He wrote that if man lived in love and charity he would understand the Word — and not the other way around. He claimed that he spoke with demons and angels, that he spoke with spirits on other planets, that he had visited both heaven and hell. Emmanuel Swedenborg was a scientist-turned-mystic whose extraordinary accounts went on to fascinate many artists and intellectuals. Not just Isaac Pitman but Ralph Waldo Emerson, William Blake, Immanuel Kant, Carl Jung, August Strindberg, Jorge Luis Borges, George Inness, Honoré de Balzac, Helen Keller, Czesław Miłosz, August Strindberg, W. B. Yeats.

Emmanuel Swedenborg spoke to the angels, but more than that, he listened. The angels told him about their language and how it differed from the language of men. In Heaven and its Wonders and Hell, Emmanuel Swedenborg described the speech of the angels. Angelic speech, wrote Swedenborg, has words and is audible, like the speech of men. Angels, like men, discuss a variety of subjects: moral and spiritual as well as domestic and civil. But this is where the connection ends. In heaven, everyone has the same language, so everyone in heaven is understood and understands. This is because language in heaven is not learned but instinctive. In heaven, speech corresponds directly to pure thought and feeling. When an angel expresses thoughts, it is wisdom; when an angel expresses feeling it is love. When people speak, their words are not analogous to their ideas and feelings — speech is mediated thought and feeling for people. When angels speak they can express in one word what people cannot express in a thousand. Therefore the books of angels are smaller than the books of men.

This purity makes the speech of angels more like pure tones. Angelic speech, wrote Swedenborg, is like a symphony; thought and speech are in complete harmony. “The tone of the voice in speaking,” wrote Swedenborg, “separate from the discourse of the speaking, and grounded in the affection of love, is what gives life to speech.” The angels told Swedenborg that man’s first language was an angelic language because it came right from heaven. Swedenborg decided that there was a spiritual or angelic speech still inherent in every person — only people didn’t know it. But Swedenborg knew it because he, among men, had spoken with the angels.

Most of us don’t get a chance meet angels. If we did, we wouldn’t know what to say. Isaac Pitman was trying to bridge this gap — perhaps he thought he had found an answer in Swedenborg. Human speech could never directly express thoughts and feelings, because this would make human words divine. But human speech was a lot closer to thought and feeling than writing, which was just another mediation. If written language could be streamlined to directly express speech, writing could be a more immediate expression of people’s thoughts and feelings. To achieve this, writing could focus more on tones than letters, like the angels. The spoken word could flow easily from one person to another. When that word was written down, the writing could express the word’s richness, without losing its meaning. Writing could be closer to wisdom and love.

Isaac Pitman absolutely believed in a universal shorthand that could be used one day as a tool for the discovery and regulation of man’s spiritual state, “as the pocket chronometer is for the discovery and regulation of time with reference to the present life.” Remember Pitman’s motto was ‘time saved is life gained.’ But Isaac Pitman was not interested in saving time. He was looking — in language — for a more direct connection to meaning. In an 1835 letter written to the Bible Society, Isaac Pitman signed, “yours in Him by whom the prophets wrote and spoke,” a signature that proclaimed the gospel of shorthand.

Isaac Pitman was a serious child. He had a delicate constitution and was prone to fits of fainting. Because of this, he dropped out of school at age 13. But he was an eager student. Young Isaac read Pope and the Psalms; his favorite book was Paradise Lost. He didn’t know other people who read these books, so he could never discuss them. Once, Isaac discovered an extremely interesting book called the Iliad, which he was sure no one had read. Young Isaac grew frustrated — there were so many words that he understood but did not know how to pronounce, because he had never heard them spoken. The mispronunciation of words became, for Isaac, symbolic of his isolation. Isaac could not know that that one day he would be knighted for his confusion.

Sir Isaac Pitman’s shorthand is the most widely used shorthand in the English-speaking world — but the contemporary application of Pitman’s shorthand is a far cry from the universal shorthand Pitman thought mankind so desperately needed. Phoneticians could not themselves agree upon a universal system. In 1893, a man named John Robert Gregg introduced his shorthand in the United States. Gregg shorthand was thought to be faster and easier to learn. In the Americas, the Gregg system soon became the shorthand of choice. In 1897, the year that Isaac Pitman died, a machine called the shorthand typewriter — an early stenotype — made headlines when it was used to transcribe President McKinley’s inaugural address. Faster machines followed, and faster machines will come. It can no longer be said that Pitman’s shorthand is the most efficient shorthand system. It is probably not even the best. But the secretaries and reporters who use Pitman’s shorthand today might be writing in the language of angels. • 1 May 2013