If you had any lingering suspicion that Dark Knight III: The Master Race — the second sequel to Frank Miller’s hugely popular and widely influential comic Batman: The Dark Knight Returns — was little more than a cynical cash grab on the part of publisher DC Comics, just direct your eyes to the credits on the inside front cover (they’re difficult to miss).

In addition to informing you that the story is by Frank Miller and Brian Azzarello and that Andy Kubert did the penciling, etc., there’s a sizable list of people that provided the art for what are known as “variant covers” — basically alternate exterior art slapped on the same comic that retailers can get only by ordering a ludicrous number of copies. It’s a cheap ploy designed to artificially goose sales by appealing to collectors’ mania and desperation. In this particular instance, I counted about 47 names on the list (more if you include collaborations). Even by industry standards it’s excessive.

Well, so what? This is just another Batman comic, right? Just one more franchise character in an endless line of franchise characters owned by major conglomerates that we are expected to express some sort of emotional attachment towards because of a base-level emotional concept that encapsulates the character’s motivations. Dark Knight III: The Master Race (ugh, that title) is just a placeholder until the Superman/Batman film comes along, after which something else will be there to divert our attention, ad infinitum. Why get upset?

But there’s something especially disappointing and depressing about Dark Knight III, in so much as it’s hard to not regard it as a nadir of sorts for Miller’s career. Often controversial, sometimes grating and childish, occasionally brilliant, Miller’s work has transformed both the landscape of mainstream comics and the world of American pop culture in general. But his star has faded considerably in recent years, in part due to the vagaries of comics fandom and the hazards of following his own, increasingly politicized, muse. And now his presence seems to have all but vanished entirely from the comics that bear his name, which is ironic, considering how large his shadow once loomed in the industry.

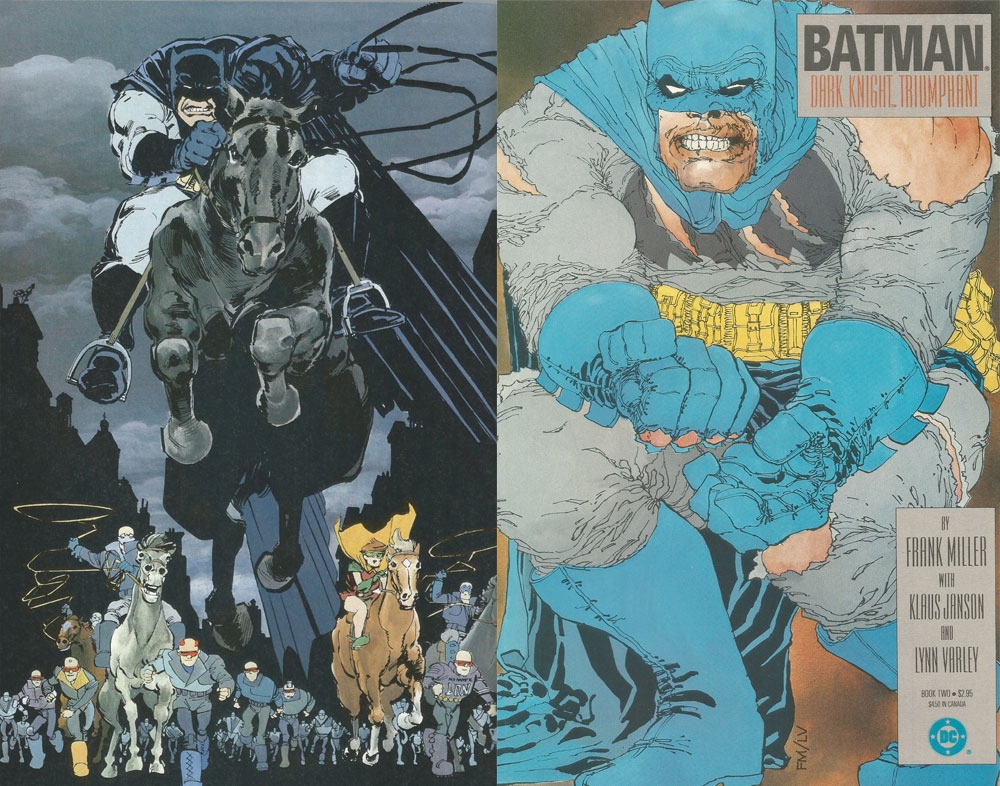

If you were around in 1986 or thereabouts, there were three comics that comics nerds would trumpet to the sky, screeching, “See, comics can be for grown-ups tooooooo,” before going back to reading New Mutants. They were, in no particular order: Maus by Art Spiegelman, Watchmen by Alan Moore and Dave Gibbons, and Dark Knight Returns by Frank Miller (ably assisted by Klaus Janson on inks and Lynn Varley, Miller’s ex-wife, on colors).

Miller was already a star in the comics firmament by that time. He had made a name for himself on Daredevil in the early ‘80s, taking a decidedly C-list Marvel hero, and infusing it with a healthy dose of noir stylishness, brooding sensibility and Catholic guilt to make it one of the company’s most popular titles. Just about every rendition of the character since, including the popular Netflix show, has in one fashion or another been a response to that run.

But Dark Knight Returns, that was something else entirely. The four-issue, prestige miniseries (squarebound and printed on heavy-stock paper so you knew it was special) pushed the violent, psychotic overtones of the caped crusader to the fore. Here we had a middle-aged, retired Bruce Wayne, who finds he simply can’t keep himself away from the cape and cowl, not just to keep an increasingly decrepit and unstable Gotham City from falling into utter chaos, but also to slate his own bloodlust. Gone is the campy Adam West attitude or the sophisticated “dark detective” from the 1970s. In their stead was an brutish, aging warrior that loved the battle a little too much. And while Miller’s ambivalence towards such a character might have been curtailed a bit by declaring him “too big” to be judged by average moral standards, he had no trouble creating a Batman you felt a little uneasy about getting behind.

Returns was formally daring as well. Miller adhered to a tight 16-panel grid throughout all four issues (eventually collected into a trade paperback, one of the first DC comics to be afforded such a treatment), adopting a sharp, staccato rhythm of small panels (often resembling tiny television screens) that would wind up the tension only to release it in burst out into high melodrama or violence. Sometimes both.

As with Daredevil, Dark Knight Returns became a template, not just for Batman (whose “canon” comics became meaner and more hard-edged) but for superheroes in general. Along with Watchmen, Dark Knight ushered in a new era where older superhero fans could ostensibly continue to enjoy their comics because they were grimmer and more violent and therefore less “childish” than what they enjoyed before (neglecting, of course, the artistry, skill, and nuance Miller and Moore infused in their own work).

Miller followed up the success of Dark Knight by moving on to creator-owned projects. He tackled the Battle of Thermopylae in 300, took the basic noir formula and amped up the testosterone level a thousandfold in his Sin City series of graphic novels, and then saw both those projects adapted into incredibly successful movies (the latter of which he he co-directed with Robert Rodriguez). Occasionally he dipped back into superhero waters (most notably with Batman: Year One with artist David Mazzuchelli) but for the most part he stayed away from Marvel and DC’s stable of heroes.

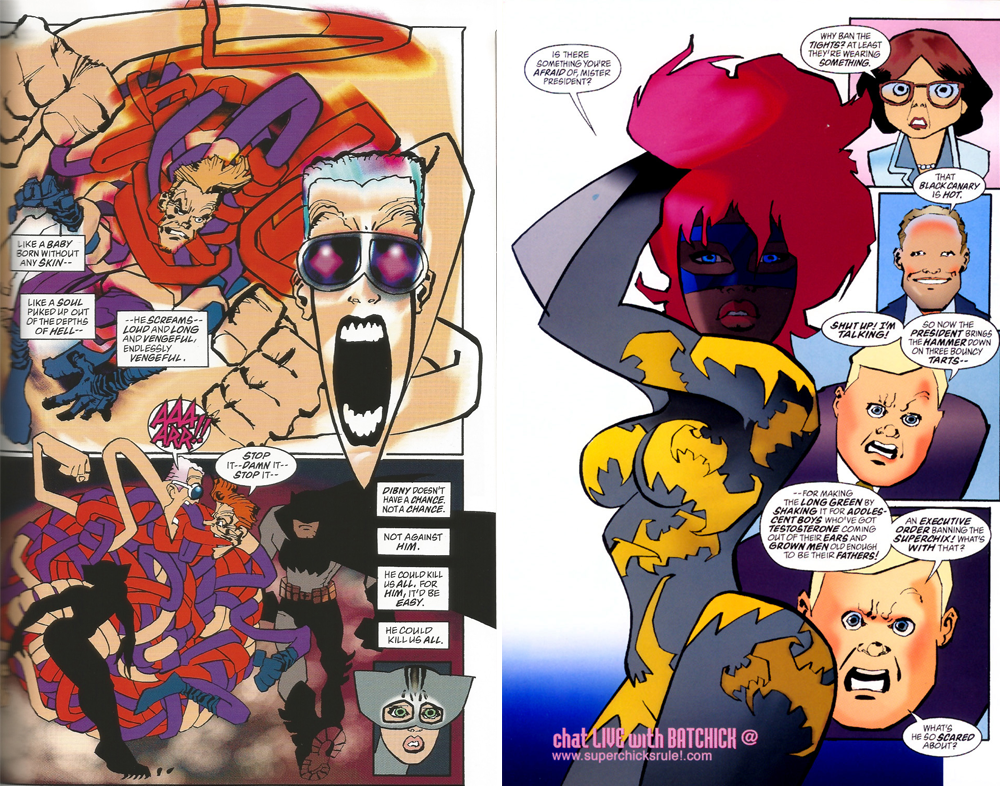

Then somewhere along the line his career took a turn for the worse. The demarcation point was Dark Knight Strikes Again, originally serialized by DC from 2001-2002. Billed as an official sequel to Returns, it diverged widely in tone and structure from the source material. If Returns was all grit and brooding atmosphere, Strikes was a candy-colored, fauvist glam show — a self-conscious mash note to DC’s Silver Age that refused to take itself seriously (or make a certain amount of coherent sense). Showing little regard for conventional narrative or even proper rendering or perspective (late-period Frank Miller seems far more concerned with images “feeling right” than actually looking right, putting him more in allegiance with alt-punk comics artists like Gary Panter), Strikes Again was not well-received by fans who hotly anticipating more of the same instead of something that favored “fun” instead.

There were other commercial and artistic failures. His first attempt at directing a movie solo, The Spirit, was a miserable flop. The second Sin City movie fared little better. Another return to the caped crusader, All Star Batman and Robin, with artist Jim Lee, received heaps of ridicule for its over-the-top attitude (google “goddamn Batman” to see what I mean).

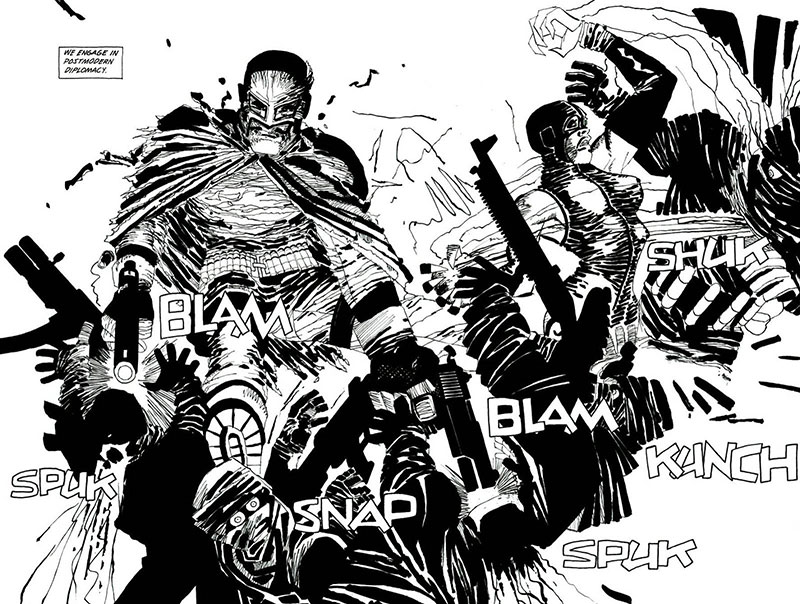

Then there’s Holy Terror, a reactionary, post-9/11 graphic novel that Miller originally designed for Batman before realizing (or perhaps being told) that such a caustic work made an ill fit for DC’s cash cow. Miller’s libertarian leanings were no secret to careful readers — his comics have always been about vengeful loners who make the world right despite interference from the corrupt and ineffectual (mostly liberals, Miller’s weakest straw man in his cadre of stereotypes). The World Trade Center attacks seem to have galvanized him into a hard-right, Islamophobic stance, however. Designed as an overt piece of propaganda (the cover echoes the iconic 1941 issue of Captain America with Miller’s hero the Fixer punching a terrorist in the face instead of Hitler), Holy Terror is an astoundingly naïve, confusing, trite, racist, ugly work, salvaged only ever so slightly by some striking panels (this is particularly true in the opening sequence, where Miller’s slashing use of white paint makes the panels seem ready to tip over into abstract expressionism). Design to irk just about every sensibility, it was met with understandable disgust and derision.

Which brings us to Dark Knight III. Despite his recent perceived failures, the possibility of another Dark Knight sequel had many Batman and Miller fans buzzing. That initial excitement was muted considerably when it turned out that Miller would be collaborating with writer Brian Azzarello — who, apart from the crime series 100 Bullets, is perhaps best known for helping pen the completely unnecessary and utterly dispiriting Before Watchmen prologue — and artist Andy Kubert. Further interviews revealed that Miller’s contributions would be minimal at best.

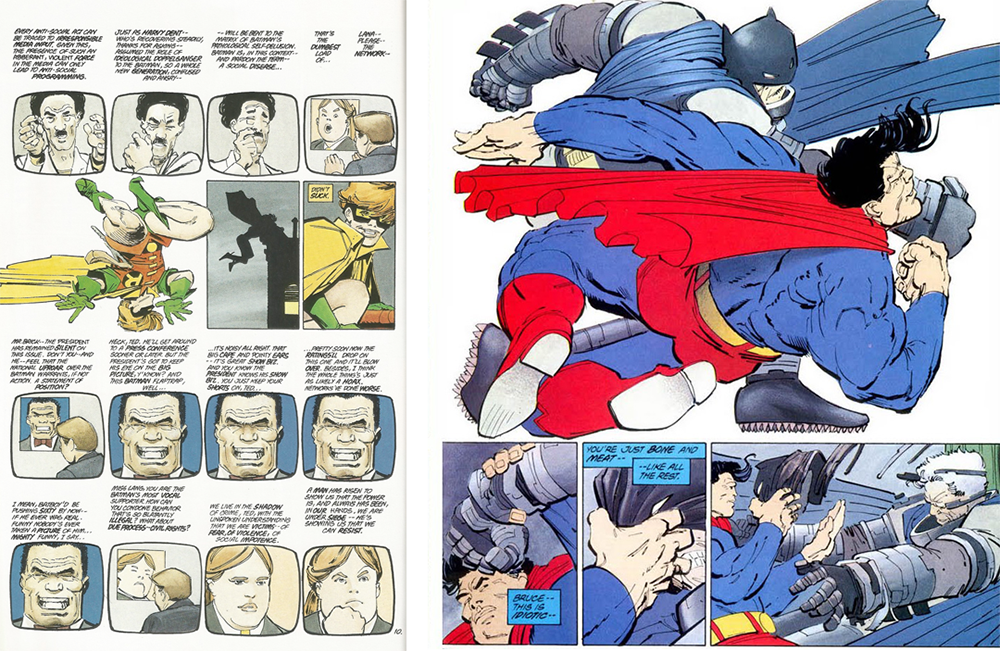

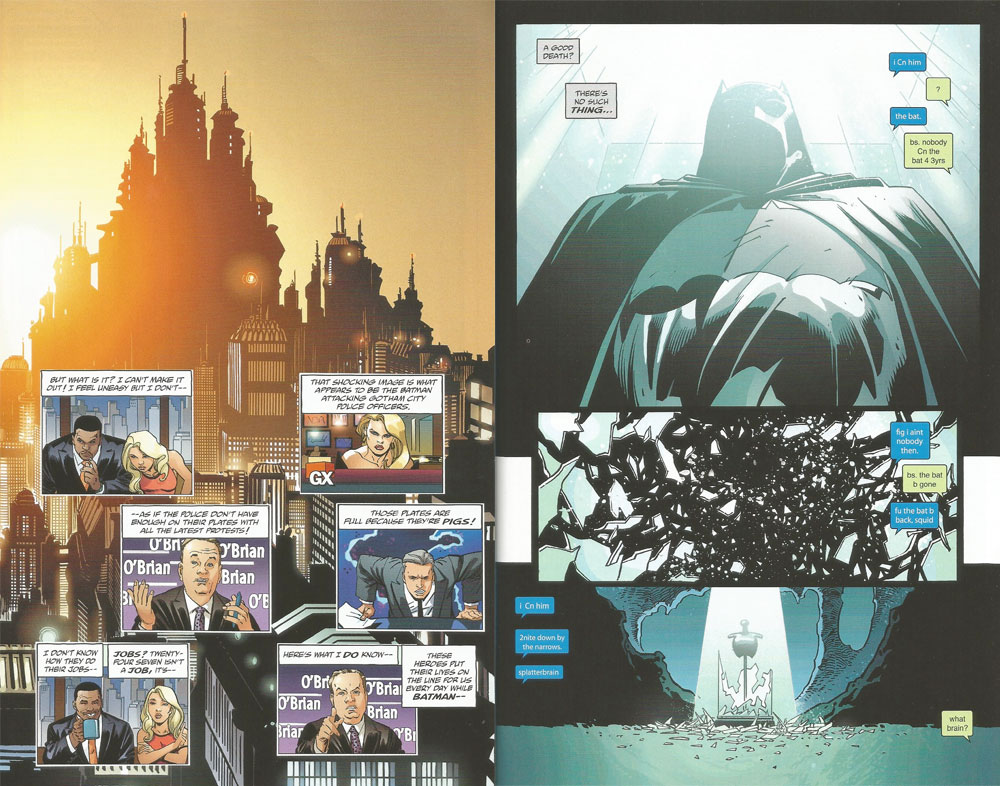

The resulting comic is depressingly average and dull. Whereas Dark Knight touched on mid-‘80s urban crime by way of creating a futuristic jumble filled with mod-clothed “mutants” that spoke in odd slang (Burgess by way of Chandler), Azzarello adopts a far more on-the-nose (and far more annoying) approach with overt allusions to Freddie Gray and Michael Brown as Batman takes on the cops to protect abused minorities. Attempts to mirror Miller’s seminal work fall woefully short — a two-page spread showing media reaction to recent Bat-shenanigans and the panels seem to float incoherently against a garishly Photoshopped future cityscape. But Miller’s unique sensibilities, however, are nowhere to be found.

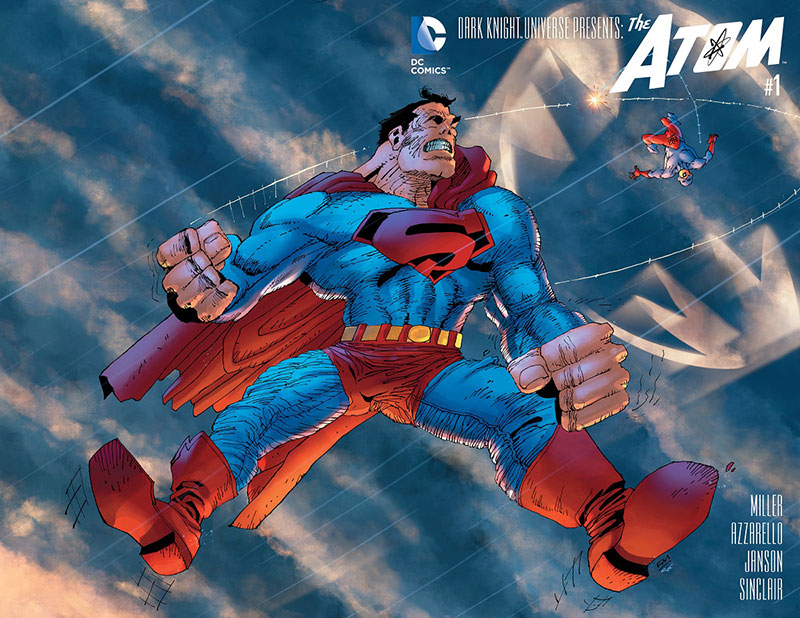

Well, not entirely. There’s a mini-comic sandwiched in the middle of the issue, a bonus side story starring DC C-lister The Atom (he can shrink real small, don’t ask questions). Miller is actually credited as the penciller on this one (again, the story is too Azzarello-ish to even see any traces of Miller’s clipped prose). Sadly, only a few panels seem to bear Miller’s trademark style — the rough-hewed line, the arched back and splayed feet and arms. Most of this comic seems to be filled in by Miller’s once and current partner, inker Klaus Janson. Perhaps the most Milleresque thing in the entire comic is the mini’s cover, which features an garishly proportioned Superman flinging (punching? It’s hard to tell) the Atom into the stratosphere. It’s cartoonishly hideous but at least it’s recognizably Miller.

So what’s going on here? Did DC want Miller’s name but little else? Or was he simply incapable of providing anything more than his name due to age, illness or pure disinterest?

But even if Miller’s best artistic days are behind him, he surely deserves better treatment than being associated with a mediocre piece of pop trash that contains few of the tics and details that won him acclaim in the first place. Despite his continued dalliances with licensed properties, and despite his insistence on alienating large segments of his audience for the sake of making reductive, retrograde political points, Frank Miller remains an auteur in a section of the comics industry that has little regard or need for auteurs. Historically, those working in mainstream comics that had both a vision and the chops to back it up — Jack Kirby, Steve Ditko, Wally Wood, and Harvey Kurtzman to name but a few — were welcome only to the extent that their originality could be watered down and compromised by a steady stream of hired hacks ready to ensure that that the constant flow of product is uninterrupted.

The difference here, of course, is that Miller has at least been paid (one hopes) handsomely for the pleasure of associating himself with Dark Knight III, and thereby being assimilated into the nerd culture machinery. Kirby, Wood, et. al., didn’t have that option — they were merely shown the door. Miller was at least paid to vanish. We’ve come so far. •