Everyone has a first time. My initiation into the sublime and absurd world of grand opera came not with my attendance at a legendary performance or under the tutelage of an impassioned connoisseur but through a chance encounter with a bizarre musical experiment conceived by Malcolm McLaren, former manager of the Sex Pistols and craven self-promoter. It happened like this. One day in the mid-‘80’s I was half-listening to an innocuous pop ballad on the radio when there arose from the drum machines and synthesizers a surging female voice unlike any I had ever heard — or at least paid attention to — before. As the aria, which turned out to be “Un bel dì” from Madame Butterfly, floated over me, my only thought was: How can anything be so beautiful?

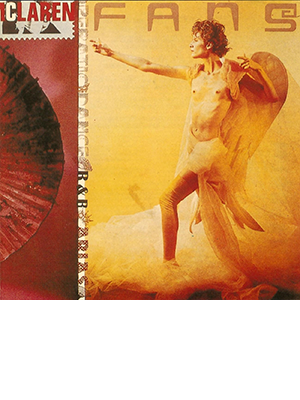

I wish I could say that from that moment I became a passionate convert to all things operatic, but in fact I went on listening to rock ‘n’ roll and even now have got around to only a dozen or so works in the operatic repertory. Yet one of those works is Madame Butterfly, and if on the radio that day I hadn’t heard Malcolm McLaren’s gleefully debased six-minute version — identified by the disc jockey as the first of six workings of Puccini on an album by McLaren called Fans — I might never have known grand opera at all. Although I no longer need to listen to opera with the electric guitars, drum tracks, and pop vocal choruses so helpfully provided by McLaren, I occasionally go back to Fans to marvel at its audacious and bizarrely sympathetic settings of some of Puccini’s most sumptuous music.

If it seems odd that one of my favorite records was made by someone who couldn’t sing or play a musical instrument, that’s nothing compared to the oddness of the music: a collage of opera, soul, hip hop, electro pop, and spoken narrative that ought to collapse from its internal contradictions and, who knows, maybe even does. Being a concept artist, McLaren didn’t have to worry overmuch about the music; other people, mostly uncredited, could take care of that. Fans survives McLaren’s brazen talentlessness because the concept animating it is so ingenious and because McLaren was smart enough to hire accomplished musicians to execute the concept — even if scarcely any of those musicians, aside from the producer Robbie Kilgore (clearly the guy who made the whole thing work), were identified on the album packaging. Furthermore, McLaren already had some experience mixing radically different musical modes into high-concept bricolage. His Duck Rock (1983), which transposed hip hop scratching over world music samplings and old fashioned folk songs, had a year earlier paved the way for the more daring juxtapositions of Fans. Actually, some people consider Duck Rock, which my reliable Rough Guide to Rock calls “the first postmodern record,” more daring than Fans. But it doesn’t have Puccini.

“Madame Butterfly (Un bel dì vedremo),” as the first album track is called, begins with a synthesized vocal frequency on one note followed by the industrial clacking of a drum machine. A “Japanese” theme is then introduced on another synthesizer, followed by an “American” theme played on a cowboy harmonica: four genres in about 30 seconds. It gets even weirder when McLaren, in his Englishman’s attempt at the flat intonation of Lt. Col. Pinkerton, starts reciting a Classics Comics version of Butterfly’s “tale of woe.” At “Take it away, Cho-Cho,” the unidentified soprano at last enters and transforms all that trash into Puccini-esque sublimity. As it happens, the trash is pretty nearly sublime too — and I haven’t even mentioned the second, pop Butterfly (“My white honky, I do miss him … Someday soon he’ll come around / Just to stop my nervous breakdown”) or the popping bass that amps up the rhythm as the song goes on.

Maybe Butterfly’s aria sounds so wonderful set against McLaren’s shameless vulgarity because Puccini, no purist himself, was hardly one to disdain crowd-pleasing effects. When years ago I first read the plot summaries in Kobbe’s Complete Opera Book, I was amazed at the sheer garishness of it all: haughty aristocrats, innocent virgins, vengeful humpbacks, gibbering madwomen. This was the lofty art form the ignorance of which was supposed to make me feel abashed? I had seen heavy metal acts with more decorum than Lucia di Lammermoor. Admittedly, the librettist rather than the composer tended to supply the necessary vulgarity, but if Verdi, Donizetti, and Puccini were comfortable with accomplished hackwork, why shouldn’t Malcolm McLaren be? Grand opera is one of the original high/low propositions. If there’s more low than high in McLaren’s versions, they draw nonetheless on something powerfully demotic in the nature of the art.

Five of the six songs on Fans recycle bits from Puccini. The one non-Puccini song is “La Habanera” from Bizet’s Carmen, which, for me, doesn’t quite work. Maybe it’s not vulgar enough. Turandot, shameless even by Puccini’s standards, lends itself better to McLaren’s violations. In “Fans (Nessun dorma)” a besotted groupie composes a mash note to her idol of the moment, a singer famed, apparently, for his rendition of “Nessun dorma,” the glorious romanza of which we hear behind the hilariously banal gushing of his fan. It’s an interesting conceit — opera singers as rock stars and opera fans as celebrity worshipping obsessives — and, as I have seen any number of times at the Metropolitan Opera House, one not far removed from reality. The romanza floats up behind the drums, keyboards, and whatnot, but given the loveliness of the melody sung by the addled groupie in the manner of a pop diva, it emerges with all the more contrapuntal force. Rarely have lyricism and lewdness been so winningly conjoined, and I wish I knew whom to praise, but all the liner notes say is, “Opera recordings made at the Unitarian Church, Belmont, Boston, Massachusetts by Stephen Hague and Walter Turbitt.” It’s possible that a connoisseur would dismiss the vocal excerpts recorded by McLaren and his crew as mediocre or worse, but sometimes there’s something to be said for the cultivation of ignorance. Every time I go to the opera I’m amazed that any human being can sing so beautifully. Even the singers disdained by the cognoscenti sound miraculous to me. The day may come when I’ll be able to distinguish a canzone from a canzonetta or detect a hint of strain in a soprano’s coloratura. But what’s the hurry?

The three remaining songs on Fans are no less remarkable or appalling, depending on how you feel about the sanctity of grand opera. “Boys Chorus (Là, sui monti dell’est)” counterpoints the boys’ chorus from Turandot against a raw electric guitar and McLaren’s shaggy-dog recitation of his days as a miserable schoolboy; “Lauretta (O mio babbino caro)” uses the aria from Gianni Schicchi as the foreground to a Harlequin Romance retelling of Puccini’s love story, sung by another wonderful and unnamed pop balladeer; and “Death of Butterfly (Tu tu piccolo)” returns us to McLaren’s weirdly beside-the-point reflections as Pinkerton (“Gosh, I wish Suzuki would be quiet!”) against Butterfly’s dying aria. I adore these songs, but a man at the Metropolitan Opera House once yelled at me for exchanging seats (well before the overture was to begin) with a woman who wanted to sit next to her companion, so I guess I’m not the best judge of operatic decorum.

It may be that Malcolm McLaren’s Fans is little more than a clever novelty item with classical pretensions, but I think that McLaren’s cleverness points to a profound intuition about opera, namely, that it is (or at least can be) a music of the masses. Although the higher reaches of the art may be beyond the capacity of the likes of me, at the very least I can only assent to McLaren when, over the chorus of “O mio babbino caro” he asks, “Do you hear that? Ain’t that lovely?” •