Following the Cold War, the claim that grand historical narratives had become obsolete was frequently made. The “dialectic of history,” which was supposed to replace capitalism first by socialism then by utopian communism, turned out to be a figment of Karl Marx’s imagination.

But it was hard for many people to do without grand historical narratives which attempt to explain the present and predict the future. In the generation after the fall of the Berlin Wall, neoconservatives — that is, former leftists or liberals who had found a new home on the political right in the U.S. and Europe — came up with a quasi-Marxist historical determinism of their own, proposing a “global democratic revolution.” Like Marxists, many neocons believed that the future could be helped to arrive by violence, in the form of American wars of regime change or subversion in Iraq, Afghanistan, Libya, and Syria.

Related to neoconservatism, though not identical to it, is neoliberalism, which emphasizes the power of economic forces more than the internal structure of states. For neoliberals since the 1980s, “globalization” is an unstoppable force which will sweep away barriers to trade, investment, and immigration. To suggest that countries could resist globalization or employ it selectively for their own national purposes was to take a doomed stand against historical inevitability. And who wants to be on the wrong side of history?

Neoconservatism and neoliberalism are relatively new as deterministic historical grand narratives go, but they have not aged well. While some areas of the world like Latin America have shed authoritarian regimes for more-or-less functioning democracies, the world’s most populous country, China, remains a one-party dictatorship, and shows no sign of transitioning to multiparty democracy. In India, Russia, and Turkey, what Fareed Zakaria has called “illiberal democracy” combines multiparty systems with charismatic strong-man rule and appeals to nationalism.

Nor did globalization prove to be an irresistible force. The most successful developing countries of the last half century — Japan, South Korea, and Taiwan — succeeded precisely because they rejected free market economics in favor of statist versions of capitalism involving industrial policy and mercantilist trade policies. The post-Cold War experiment in liberalizing international capital flows turned out to be a disaster, first in the financial contagion associated with the Asian financial crisis in the 1990s, and then in the Great Recession, the worst global economic collapse since the Great Depression of the 1930s.

Oh, and the free flow of immigrants in the globalized world? Among progressive intellectuals and activists it has become an article of faith that it is illegitimate for countries to control immigration by laws backed up by penalties. These thinkers and activists are living in a dream world. In the real world, a popular backlash against mass immigration is shattering existing party systems by empowering nationalists and populists like Donald Trump in the U.S. and Marine Le Pen in France. From the American Southwest to the national boundaries of Europe, borders are being fenced and patrolled to keep the foreign poor out of the richer, more developed nations.

In light of the failure of the Marxist, neoconservative, and neoliberal historical narratives, it is worth sharing the skepticism of H.A.L. Fisher in his 1935 book A History of Europe: “Men wiser and more learned than I have discerned in History a plot, a rhythm, a predetermined pattern. These harmonies are concealed from me.”

It must be noted, though, that approaches to politics that ignore historical changes too much can be as misguided and dangerous as those that see history as the unrolling of some providential plan. A politics that is too ahistorical can be as misconceived as the politics of historical determinism.

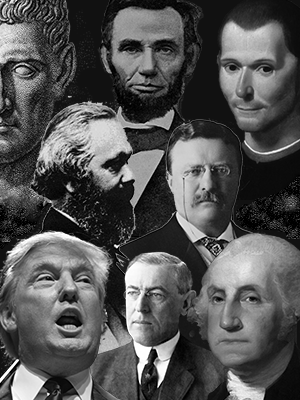

This is the case with so-called Straussian conservatives in the United States in the tradition of the German-American political philosopher Leo Strauss, particularly the West Coast Straussian School. Members of this political sect contrast the true, universal, and eternal principles of the American Founding, as expressed in the Declaration of Independence, with “historicism” or the idea that political systems should evolve over time as society evolves. According to the Straussian Right, early 20th-century Progressives like Theodore Roosevelt and Woodrow Wilson, influenced by German scholarship, replaced America’s founding principles of inalienable rights with historicism and pragmatism.

The goal must be to restore the American republic in the form that it was before Roosevelt, Wilson, and other progressives betrayed it. The election of 1912, pitting two progressive candidates, Theodore Roosevelt and Woodrow Wilson, against a conservative, William Howard Taft, is viewed by Straussian critics of progressive “historicism” as a turning point in American history. In other words, the U.S. has been on the wrong track for 104 years.

This summary of Straussian conservatism shows that even anti-historicist political thinkers cannot escape having a theory of history. In the case of political theories based on timeless truths, the corresponding historical theory is almost inevitably one of conspiracy and betrayal. If there really are timeless principles known to previous generations that should shape our regime and our present-day regime is not shaped by them, then there must have been some act of treason in the past. History becomes a melodrama, in which the good guys are betrayed by the villains. In this case, the good guys are the Founders and Lincoln, and the villains who betray their legacy are Theodore Roosevelt, Woodrow Wilson, and Franklin Roosevelt.

Such an approach to politics is idealist in the sense that it makes material and economic and demographic factors vanish and reduces politics to doctrinal debates among professors and politicians and journalists. But it is clear in hindsight that a century ago industrialization, urbanization, and mass European immigration in the U.S. created challenges for which no answers could be found in the practice of 18th- and 19th-century America. As for the theory of the Founders, the Straussians to the contrary, the two Roosevelts and Wilson thought they were rescuing American democracy by timely reforms, jettisoning some traditions and institutions which were anachronistic in an industrial-urban society in order to preserve more important values.

This suggests that the best way to think about politics in the context of historical time is neither a deterministic historical grand narrative nor an approach to politics that equates reform with betrayal. Here we can learn from premodern theories of democratic or republican government like those of Aristotle and Machiavelli which were not embedded in some overall theory of inevitable historical progress.

If the conditions are right, then according to classical republican theory a society may be able to create and sustain a republican form of government. But success in one country does not mean that history with a capital H is promoting a wave of republicanism throughout the world. On the contrary, in ancient and medieval times, republics were rare and isolated exceptions to the rule of monarchical government. Indeed, it is only in the last generation that democracy, often in some partial and imperfect form, has become a relatively widespread form of government.

This view of republicanism — including its modern form, the democratic republic on the nation-state level — as something fragile and contingent and local, not a guaranteed by-product of some “wave of the future” that cannot be resisted, was taken for granted by generations of American leaders and thinkers. The phrase “the American experiment” uses “experiment” in the old-fashioned sense of a test or trial. Put to the test, modern democracy on the scale of the modern nation-state may succeed, or it may fail.

In the “Circular to the States” published upon his retirement from command of the continental army in 1783, George Washington argued that it was up to Americans themselves whether American democracy succeeded or failed: “if their Citizens should not be completely free and happy, the fault will be entirely their own.” The U.S. could flourish as a federal republic — or it could collapse into civil war or dictatorship. “[I]t is yet to be decided, whether the Revolution must ultimately be considered a blessing or a curse — a blessing or a curse not to the present age alone, for with our fate will the destiny of unborn Millions be involved.”

Clearly George Washington did not believe in the inevitable worldwide triumph of democracy. He did not even believe that the triumph of democracy was inevitable in the territory of the newly-created United States of America.

Nor did Abraham Lincoln believe that the global triumph of democracy was inevitable. On the contrary, during the Civil War he argued that the breakup of the U.S. would tend to discredit democracy as a form of government in the eyes of foreign observers. This is the theme of his Gettysburg Address, which many recite but few understand: “Now we are engaged in a great civil war, testing whether that nation, or any nation so conceived [in Liberty] and so dedicated [to the proposition that all men are created equal], can long endure.” If the American Union failed the test and disintegrated following an election, then other nations might conclude that democracy was an unstable and doomed system of government likely to lead to state breakdown, civil war, and mass slaughter.

As George Washington had said earlier in a similar context in his “Circular to the States”: “This is the time of their political probation, this is the moment when the eyes of the whole World are turned upon them.”

In the view shared by Washington and Lincoln, history does not guarantee the success of the democratic, or more precisely the democratic-republican nation-state. On the contrary, history is constantly throwing up challenges, in response to which the republic must adapt if it is to survive. These challenges can be internal (the division among slave states and free states that led to the Civil War). They can be external, like the world wars and the Cold War. They can be economic, like the challenge of industrialization around 1900, the Great Depression of the 1930s, and the Great Recession and the challenge of automation in our time.

The American political order so far has passed a series of tumultuous historical tests. But only one failure is necessary, to turn national democracy in the U.S. into some other system that is worse.

Without principles, we become enslaved to this or that determinist theory of history. But without a theory of historical challenges and opportunities, we become enslaved to outmoded practices and anachronistic institutions. The challenge is to realize enduring ideals by means of new practices and reformed institutions in response to changing historical conditions. It is a test which Americans might well flunk. If they do, then in the words of George Washington, the fault will not be that of history. Rather, “the fault will be entirely their own.” •

Feature image art by Maren Larsen. Source images courtesy of Internet Archive Book Images, Friedrich Karl Wunder, Pach Brothers, Gilbert Stuart, Ambroise Tardieu, and Santi di Tito via Wikimedia Commons and Gage Skidmore via Flickr (Creative Commons).