The past centuries, if not millennia, have been characterized by the unprecedented spread of certain plants to other continents. Crops such as bananas, tomatoes, potatoes, corn, and rice are classic examples. Many others did not require human help; their seeds were spread by wind and birds and encountered favorable conditions, as has happened since time immemorial. Some plant types are particularly aggressive, spreading and replacing other plants. They are usually called “invasive” types, and they sometimes succeed with the involuntary help of humans. Now, due to climate change, vegetation zones are changing: Conifer forests, for example, are spreading to tundras, and in the tropics, the rain forest is becoming denser.

The plant in question, however, stubbornly resists establishing itself in other places for the simple reason that its spectacular seed is so large and heavy. The name of the plant it is adjoined to – a type of palm tree – is Lodoicea maldivica, even though it doesn’t grow in the Maldives as one may be inclined to think. This peculiar tree goes by the names of Sea Coconut, Coco de mer, and Coco de Maldives. It has also been called Lodoicea sechellarum, which comes much closer to the truth. Lodoicea is related to Lodoicus, or Latinized Louis, christened in honor of King Louis XV of France.

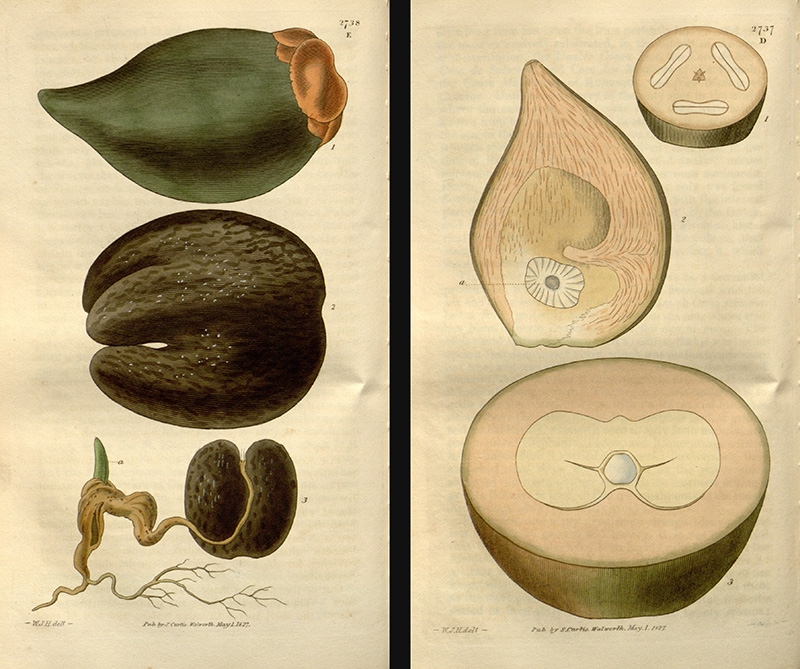

It has the largest fruit (15 to 20 inches in diameter, weighing 30 to 60 pounds), the heaviest seed (over ten pounds), and the largest female flower of a coconut: It is a plant of superlatives. Botanists speak of “island gigantism.” It is also one of the rarest plants in the world. And, as one might expect, its life span also follows other laws. The tree takes an average of 20 years to blossom and only then can the sex of the plant be determined: The female flower resembles a breast, the male, a penis. The fruit takes about ten years to ripen. Once a nut falls down, its one to four seeds are released and three to six months have to pass until germination. As the soils are not very rich in nutrients, the young seedlings use the energy stored within the giant seeds. Another year passes until the first leaf shows. It all seems to be governed by the principle of slow motion, but with lasting effect: A tree can reach an age of several hundred years.

The fruit of the tree, or a remnant of it, has been known much longer than the actual tree. People strolling the beaches of India, Sri Lanka, the Maldives, Indonesia, and South Africa long wondered about the origin of the hollow two-headed nuts arriving at their shores. Hence the legend that this fruit must belong to a giant tree that grows at the bottom of the water, like a mermaid swimming to the surrounding lands. Or did it grow on an island that could only be found by those not seeking it, as an obscure 17th-century document claimed?

The peculiar shape of the giant fruit, reminiscent of a double melon or bottom, only compounded the enigma. “Love nut” remains one of the coyer and more politically correct names given to the object. Adam Leith Gollner, in his book The Fruit Hunters, calls it “easily the sexiest fruit in the plant kingdom.” Others have called it “lady fruit” or, well, “butt nut.” Over time, the nut’s shell was in high demand as a collector’s item, appearing as an attractive gift in Europe, often adorned with ornamental carvings. The hardened inner part has been used just as ivory. A trade between the continents ensued, and the nut was highly sought after. In Japan, it was even considered holy. As Gollner writes: “The crowning glory of King Adolphus Gustavus of Sweden’s curiosity cabinet was a gold-mounted, coral-sprouting coco-de-mer goblet being hoisted aloft by a silver Neptune.” Sometimes it was called the “billionaire’s fruit.” Given the evident craze surrounding it, it seems almost a miracle that the tree has survived.

It was only in 1768 that the French explorer Marc-Joseph Marion du Fresne (1724-1772) found the origin of the nut to be Praslin, one of the Seychelles’ islands that had only been discovered a few years earlier. The British general Charles Gordon (1883-1885) later compared the forest with the “Garden of Eden,” the palm tree at its center becoming “the tree of knowledge.” He even drew a map that showed the biblical Garden of Eden extending across the Indian Ocean to the Seychelles, with the mythical forest on Praslin as its center. Was the “forbidden fruit” really the “coco de mer?”

As we now know, plant and animal species have been evolving in complete isolation for up to 70 million years on these granite islands. Therefore it is likely to be a remnant of the hypothesized ancient continent Gondwana, which ceased to exist when the continental plates drifted apart some 200 million years ago.

Another fantastical idea arose from the realization that there are female and male trees. During stormy nights, when nobody dares enter the forest, the sea coconut palm trees are believed to celebrate their wedding. The phallic-like flowers of the male trees then mate with the “bosom” of the female tree. Whoever came to observe them would have to die, or so the legend went. In fact, it has still not been understood how pollination takes place – how the pollen moves to the female flower. Is it with the help of insects, birds, or geckos’ tongues? Or perhaps the wind?

The contents of the nut are edible. Members of the German deep-sea explorer ship Valdivia landed in Praslin in 1900 and prepared a salad from the custard-like flesh, which, with its almond-like taste, was “the finest delicacy.” Nowadays, the trade in Coco de Mer is strictly controlled. Buying or selling one without a permit is subject to a fine of 800 dollars and two years in jail – in fact, there are dozens of poachers currently serving jail sentences. The misunderstanding that the fruit is an aphrodisiac only served to curb demand: How could anybody be so foolish to deduce function from form?

Another riddle remains, a rather practical one, and that is: How did the nuts make their way into the water? Contrary to the way the tree is displayed near the shore on a beautiful plate in Historia Naturalis Palmarium by Carl Friedrich Philipp von Martius (published in Munich 1823-1850) it is known that the trees never grow close to the shore. A friend of mine who visited the islands a few years ago (and who kindly contributed the photo of the nut next to the little iron stove) confirmed this. Since there aren’t any monkeys on these islands – who would have had a hard time carrying them anyway – do we have to resort to the mythical giant bird Garuda for an explanation? It’s tempting, but let’s keep to the facts: Heavy tropical rainfalls and streams are much more likely to have done the job. While the complete nut is heavier than water, once the inner parts have completely dried out, it can float in water.

The occurrence of this palm tree is limited to the Vallée de Mai on Praslin and to the much smaller neighboring island of Curieuse which have both been declared UNESCO World Heritage Sites. According to the current count, there are 21,000 trees on Praslin, among them 2,900 females, and another 3,800 on Curieuse. They grow in the thicket of gigantic, fan-like leaves that protect the plant, with its slim trunk extending vertically into the sky, from sun and rain. And despite the fact that they grow closely together, apparent inbreeding does not seem to be an issue. This plant really lives in a world of its own. In the twilight of the jungle, the Seychelles Black Parrot lays his eggs in toppled trunks of the palm tree. The Seychelles Bulbul, a bird, can be heard. With a bit of luck, you can spot a tenrec – a mammal resembling a hedgehog. A little community of animals inhabits the tree.

Botanical gardens around the world have gone a long way to grow the demanding palm tree on their grounds, but only very few places have succeeded. The Peradeniya Botanical Gardens near Kandy, Sri Lanka, one of the former satellite gardens of Royal Kew Gardens and for many today the finest of its kind in Asia, sports one that even bears several nuts. In other climes, it is more difficult. Hilke Steinecke, a scientist at Frankfurt’s Palm Garden, has followed the development of one such palm tree for more than 20 years. Growing them is complicated enough, as heat and humidity have to be high and just right. Even with the help of subterranean heating, there is no guarantee that the plant will flourish. But once it grows, it grows – up to 100 feet in height. The botanist now faces the problem that its leaves touch the ceiling of the Tropicarium’s Mangrovarium – the botanical glass house. There is no space for further expansion. “Cutting the tip of the palm tree is impossible, because this is where the shoot sits, the heart of palm. Once the heart is destroyed, the palm tree dies.” So at some point there is no alternative to cutting the tree and simply hoping that a young one will take its place. And there is another complication that botanical gardeners outside the tropical realm have to contend with: A seed just never grows in a greenhouse. Artificial pollination of the sea coconut palm has only been achieved in the rarest of cases. •

Images courtesy of the author, David Stanley, and Stewart Morris via Flickr (Creative Commons).