Any given year of one’s time roaming the earth unavoidably has some effect on who they are as a person.

It is perhaps especially so when a person has just turned 14, been forced the previous year to swap daily life with his family for the company of strangers and is on the cusp of being exposed to what will more than half a century later still be universally recognized as some of the most revolutionary and unique popular music ever committed to tape.

These were the circumstances under which a young lad named Robyn Rowan Hitchcock found himself in the titular year of his new memoir, 1967: How I Got There and Why I Never Left.

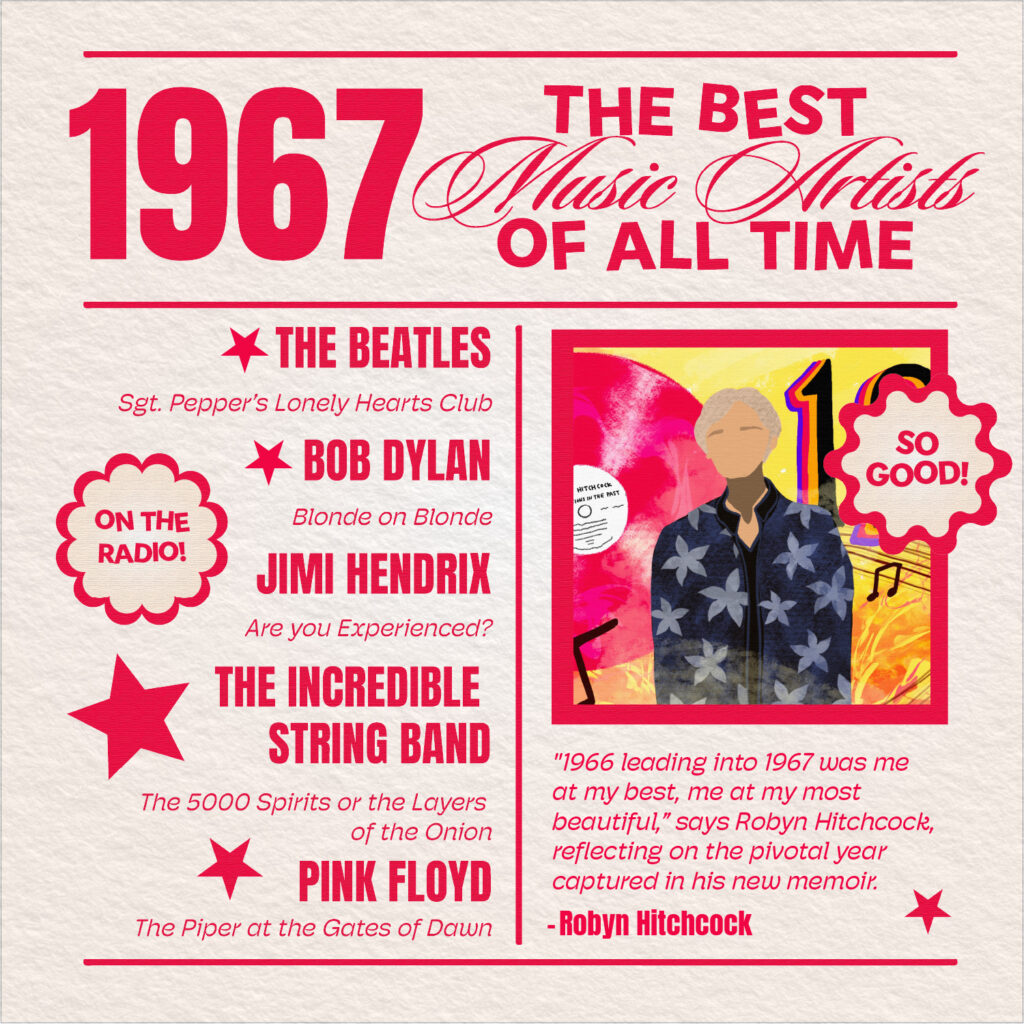

“1966 leading into 1967 was me at my best, me at my most beautiful,” the 71-year-old singer-songwriter told me in a recent Zoom interview. “Me at my freshest and smartest.”

“I was accelerating just as the world was accelerating,” he continued in his trademark articulateness. “So, it was an extraordinary coincidence to reach adolescence just as the world leaped into modern life, or the beginnings of it.”

(Hitchcock thanked his wife, Emma Swift, a fellow singer-songwriter, for the idea of picking one phase of his existence to preserve for posterity.)

Robyn Hitchcock has always been more than a bit of an enigma.

With that somewhat unexpected “y” in his first name and a surname that is inextricably linked to terror, tenseness, and unpredictability, one cannot help but wonder about the thoughts that linger in the brain that sits below that still-full head of snowy white hair and behind those frequently mesmerizing peepers.

However, Robyn Hitchcock is far from purposely obscure or reclusive.

On the contrary, he is exceedingly active on social media, frequently posting selfies in whichever city surrounds him or captioning pictures of his younger self with the story of the events that were unfolding at the time the image was captured.

In fact, he credits the ability to impart such information to all who are interested with helping him write 1967.

“I’ve been eased into [writing] by social media,” he explained to me. “Instagram, Facebook, Twitter (currently known as X), Patreon. All the things that have arisen in the last 20 years that provide what is lovingly known as content.”

(Hitchcock’s father, Raymond, published the first of his several novels, Percy, in 1969. Two years later, the book was adapted into a film whose soundtrack was by a band whose songs — specifically “Waterloo Sunset” and “Autumn Almanac” — figured prominently in Robyn’s 1967 soundtrack, The Kinks.)

“The element of 1967 that I’ve never really left is the musical one,” he told me from the London hotel room he was in during our virtual conversation.

Thus, it is the music of that year that provides the main pillars of his memoir.

Among the lead players in his story were The Beatles, Jimi Hendrix, The Incredible String Band, Pink Floyd, and the artist whom he described to me as “arguably the prime mover, the star of the book,” Bob Dylan.

In January 1966, the soon-to-be 13-year-old Hitchcock said “Bye-Bye, daddy” and “Bye-Bye, mummy” as they deposited him at Winchester College, a fancy and costly boarding school about 40 miles from the home of his parental units.

The Beatles had released Rubber Soul the previous month and would unveil Revolver in August.

Dylan, meanwhile, was in the early stages of recording the double LP Blonde on Blonde the month that Hitchcock began to traipse the grounds of Winchester (where one of his fellow “inmates,” as he calls the students, was an upperclassman named Brian Eno).

In a 2017 interview that I did with him, Hitchcock called 1966 “the year of his “psychedelic bar mitzvah.”

So, given that The Beatles and Bob Dylan — arguably the most culturally impactful popular artists of the 1960s — both released their seventh albums in that year, what was it about the following one that made him want to remain there?

Personal, psychological, and physical matters aside, it was simple: it was when his ears lost their Dylan virginity.

He subsequently fell hard for the man born Robert Allen Zimmerman, becoming the type of zealot that only a self-described convert such as himself could.

Interestingly, it was “Like a Rolling Stone” from the 1965 album Highway 61 Revisited that paved the young teen’s Road to Damascus.

“That Voice,” he writes in 1967, “this is the closest I’ve yet come to the Holy Grail.”

Elsewhere — presumably without the intention of referencing another Monty Python movie — he proclaims, “It’s pretty clear to me that Dylan knows the meaning of life, if anybody does.”

“I was heliotropic,” was how he described it to me. “I was turning towards the light. The light was Bob.”

He first heard Dylan on the House Gramophone (he always capitalizes it), which served him in the way that the monolith does the apes in 2001: A Space Odyssey. It is his main, maybe only, source of respite within the confines “of the Victorian house in which I was expensively incarcerated” at Winchester.

Ironically, the all-knowing bard did not offer any new material of his own in the year of the book’s focus until two days after Christmas. And Hitchcock describes that album, John Wesley Harding, as “flat, beige, and not much fun to listen to” and that to him it “signaled the Great Retreat.”

Nevertheless, he remained deep in his mentor’s thrall.

“When 1967 ended,” he told me, “I most of all wanted to follow Bob Dylan, the pied piper, over whichever cliff he led me.” (Still, he lamented what became of the future Nobel Prize winner in the Reagan era: “I watched poor old Bob Dylan being completely marooned in a sort of ‘80s production, wailing like a lost soul, making records with terrible sound, I thought.”)

As for The Fab Four, whose 1967 output included Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club and the monumental double A-side “Penny Lane/Strawberry Fields Forever,” our author avers, “Through the amber of sixty years the Beatles glow ever brighter: they mean as much to me now as a white-haired pensioner as they did to the 10-year-old 70 percent–grown me.”

Citing Sgt. Pepper, Jimi Hendrix’s Are You Experienced?, The Incredible String Band’s The 5000 Spirits or the Layers of the Onion, Pink Floyd’s The Piper at the Gates of Dawn, The Doors’ first two albums, The Velvet Underground and Nico, Mr. Fantasy by Traffic, and Forever Changes — which did not hit the UK market until 1968 — by Love (whose lead singer Hitchcock celebrated in his 1993 song “The Wreck of the Arthur Lee”), Hitchcock described his personal annus mirabilis’s music to me as “a pretty long list of things that can’t be beat” and opines in the book that “music budded and came to fruition then in a way that — to my ears — has never been surpassed.”

But, I always ask people who say such things, doesn’t everyone think that the music that they heard during their most carefree (though certainly not stress-free) and impressionable years is the best ever, an idea lampooned by The Hard Times here and here?

Hitchcock volunteered in our aforementioned interview that the music that he worships is largely a function of when he was born (March 3, 1953):

“If I’d grown up a decade later, listening to For Your Pleasure [Roxy Music] and Aladdin Sane [David Bowie] and Electric Warrior [T. Rex] or something, I’d probably be making a different kind [of music] . . . Or another decade after that, and I was listening to Murmur [R.E.M.] and The Queen is Dead [The Smiths] and Doolittle [The Pixies].”

He also directly addresses the question on the last page of 1967:

“Perhaps that’s simply because my particular class of ‘boomers’ came of age as the psychedelic upheaval broke through the tarmac of reality. Kids reaching adolescence in the age of Harry Styles surely feel as intensely as we did — but I wonder if they feel as intense about the music made now as we did about its hippie ancestors.”

But why would he doubt the sincerity of young people’s enthusiasm?

After all, Hitchcock writes in the book that Dylan was, “more than either of my more sophisticated parents can take: something about his sound disqualifies most of the older generation from enjoying him.”

Were they just as correct to doubt the quality of the music their son preferred as Hitchcock is to doubt that of the music currently in the Top 40?

When I asked him to clarify in an email, he answered:

“Pop music seems to be written on, by, and for machines these days, although there are plenty of good ‘indie’ artists. Gillian Welch & Dave Rawlings, Kelley Stoltz and Frøkedal Familien all have lovely new albums and are doing beautiful shows. I just wonder if there have been many memorable pop songs since the 1990s. Of course, I might not recognize them as memorable anyway, being the age I am.”

Exactly. As we age, we take on new responsibilities, our priorities shift, and our minds — as much as we might like to think otherwise — become less open to new experiences. Fifty-seven years from now, fans of Harry Styles, Taylor Swift, Drake, Dojo Cat, etc. will probably be just as put off by the biggest hits of 2081.

But there is really no arguing with the quality of the music of the year of which Hitchcock writes, “I am grateful that the stopped clock of 1967 ticks on in me — it’s given me a job for life.”

For evidence of the high standards set all those years ago, look no further than the book’s recently released companion album, which includes Hitchcock’s versions of songs by several artists mentioned in the book, a handful that are not, and a new original composition, “Vacations in the Past.”

“I thought I’d do them acoustically,” he told me, “because this is what a 70-year-old man with an acoustic guitar sounds like playing songs that he heard and loved 55 years ago. It’s supposed to show the mark of time.”

Although only two American artists are included on the album, Jimi Hendrix and Scott McKenzie, Hitchcock acknowledged to me that he “could very easily do an American Best-of. I could fill it up just as quickly doing The Doors, Love, The Byrds, and, of course, The Velvet Underground.” (He has all of these artists in some capacity — on proper albums, as B-sides, as outtakes, or in live performances.)

While the profundity of 1967’s musical influence on Hitchcock has been long since established, another effect did not take hold until less than a decade ago.

“The 14-year-old me decided where the 70-year-old me was going to end up, which was Nashville,” he declared via Zoom. “Nashville is where Bob Dylan was recording, and he knows the meaning of life! So, I’ve been very true to that.”

Sure enough, he moved to Music City in 2015, where his now-wife (and fellow Bob Dylan enthusiast) Emma Swift was living when they met. Hitchcock recorded his eponymous 2017 album and 2022’s Shufflemania! in the same southern metropolis where his hero captured Blonde on Blonde.

It would seem, therefore, that the erstwhile adolescent has come full circle.

However, while he might be — by his own admission — in the final arc, that circle is not yet closed.•