“How do I look?” I asked, unsure about leaving the house in just mascara.

“You always look great. You’ve got a naturally beautiful face,” John responded.

I chuckled at my boyfriend’s innocence and then spent the next month doing what I do best; obsessing over the idea that John thought this was my face. In our shared calendar “lunch with Angela” was code for “poke a bunch of needles in my face.” I had spent the last 11 years in a slow climax of one hundred units of Botox every three months and two syringes of dermal fillers every other year. In fact, I’m famous for telling people that I’m going in the ground as preserved as possible, and that’s before being embalmed.

I think altering your face is more acceptable if you’re honest with everyone but your significant other (they don’t need to know how the sauce is made). Lying about your age is old news. I recommend stating your age, then politely waiting for the chorus of, “Oh, you don’t look 38!” It’s far more humble, especially when followed by a hand wave while saying “Botox,” as if you’re talking about “this old thing?” At least, that’s how it works in my head.

When John and I first took a trip to his childhood home, I saw the usual range of photos, including the awkward teenage years in which he still manages to look charming. In each image, he looks appropriately groomed with a winning smile and piercing blue eyes. While looking at pictures of John and his siblings frolicking happily on the beach, I feel grateful for my mom, a single mom of four kids who stuffed our baby photos into hefty trash bags and piled them in a closet, or “Did I put them in that storage unit?” she wonders. “I can’t remember everything, Gabrielle; I had four kids!” If John were to brave the spiders and mouse droppings on top of the trash bags, he would open them and ask, “Who is this more Jewish-looking, horse-mouthed, birth-marked Gorbachev, and what’s up with that lazy eye?” I’d have to coquettishly answer, “Why, that’s me, lover. Your naturally beautiful girlfriend, with whom you’ve confessed your desire to procreate.”

Here is a list of names I was, mostly lovingly, called by my family growing up: Ugly duckling, hair in a light socket, flabby gabby, bucked-toothed beaver, gummy Gabbi, Gorby-Gabbi, just ugly and, my favorite: five-finger forehead. My ex-husband posted my photo in an online divorce group for angry men. They responded by calling me John Lithgow, known for his hilarious performance on 3rd Rock From the Sun and a forehead large enough to host the sun. My grandmother used to say, “You look like your father’s side of the family, except your nose isn’t that Jewish.” And to pour salt on the wound, my sister Rachael was a face model

“She’s too short for the runway, but Rachael has exquisite cheekbones, and her jawline is divine,” the modeling agent said to my mother as they walked towards the exit.

“Ready, Gabbi?” my mom asked. The modeling agent looked at me like I was Gregor Samsa, Rachael’s beetle-like sister. Who let this monster into the waiting room?

I spent most of my time outdoors, barefoot, with a delightful mixture of sticks, prickly things, and leaves caught in my swamp hair. I would wander back inside like some Virginia creature to eat meals, never noticing my offensive face. My grandmother, concerned I was going to catch the gay by being a tomboy, asked my mom, “Why don’t you buy Gabbi a little purse or something?” I responded by buying a raccoon purse that looked like roadkill and filled it with monster trucks.

I wondered how a gal like me got all caught up in appearances. It started with the hormones, which led to copious amounts of eyeliner in the seventh-grade bathroom (don’t judge, it was the ’90s). It progressed to mountainous wads of Clairol hair mousse to tame my curls, which eventually evolved to burning my hair straight. In college, I became adept at applying thick layers of Cover Girl foundation but made sure to show my boobs a lot to detract from my face. I quickly figured out that you could have an extra-large gummy smile, but with double-D breasts, no one was looking at your donkey face. While leading with ample bosom, I got pregnant at twenty-seven. After pregnancy, I remember looking at my face and thinking, “Who is that haggard version of me?”

The great thing about being a woman is that there’s always a hype girl in the bathroom ready to give you a pep talk. When my son was two months old, his grandmother came to babysit so I could have a well-deserved date night. My husband put on a Brooks Brothers blazer, Prada loafers, and Giorgio Armani cologne. I put on my best maternity dress because that’s all that fit and thanked the gods I was out of my postpartum adult diaper. I prayed I smelled like hairspray instead of spit up. My breasts began to ache and leak during our fancy dinner, so I went to the bathroom to pump a little. While washing my hands, I started silently crying. Whose body is this? Whose face is that?

As if she were my toilet fairy godmother, a woman said, “You’re doing great and you look beautiful.” This woman had perfectly quaffed hair, pouty red lips, and small peaks for cheekbones. Her skin was smooth and youthful.

“I’m sorry, I’m a mess. I just look and feel so exhausted,” I cried.

“Oh honey, this will get better when you sleep more, and you can always start Botox.”

After this visit by the Confucius of injectables, who explained how she looked like a beautiful vampire, I began to research this magical serum. Botox is injectable botulism, not to be confused with the kind found in poorly canned vegetables your Aunt Sheila didn’t seal properly. Allergan, a leading pharmaceutical company, applied for and received FDA approval for Botox in 1989. It was originally used for eye spasms but transitioned to cosmetic use in 1992. Sadly, it does not work by filling lines already formed in the skin, but it is considered preventative. As a new mother deprived of sleep, I interpreted the word “preventative” as run, don’t walk, to the nearest injector. I looked at my face and the lines across my forehead were getting deeper. The crow’s feet around my eyes were now lengthening. The deep cracks around my mouth could be seen even when I wasn’t smiling. Failing to see these new lines were hard-earned and etched with the joy of having a new baby, I called the injector.

The plastic surgeon’s office was welcoming and modern. The receptionist here looked happy and surprised to see me. She offered sparkling water and a cozy chair. It smelled like orange zest and cleaning products, which was different from my primary doctor’s office, which smelled like rubbing alcohol on top of a shart.

As a new mother, you’d think I would have weighed the pros and cons of Botox usage, but I didn’t. I’m ashamed to say I never considered an allergic reaction, pain, or even death. That’s how desperate I was to feel better about my appearance.

“Mrs. Nigmond, would you come with me, please?” The nurse, who looked as refreshed as the receptionist, gestured as she escorted me into a private room with an oversized window. The warm light painted the gray walls. “Please make yourself comfortable,” she offered while pointing towards the supple leather lounge chair. “The doctor will be in soon.” I waited and patted myself on the back, thinking about how smart I was to start this now.

“Hello, Mrs. Nigmond. So nice to meet you. I’m Dr. X. What brings you here today?”

What I wanted to tell her was that when I got out of the shower and wiped the steam off the mirror, I didn’t fully recognize the woman staring back at me. The c-section scar was still light pink even though it had been almost a year. The left side was a little lopsided from pulling stitches while making sure my husband felt loved after our son was born. He repaid my kindness with a $75.00 massage that included a $75.00 tip that magically appeared on our credit card statement. It was the first of many disturbing discoveries that would force me to be an explorer. The journey included an obsessive review of his computer and a full account of my own body. There had to be something wrong with me, right?

Instead of telling Dr. X all that, I just said “My face.”

The consultation was a full 15 minutes of me explaining everything I perceived as wrong with my face. It was like neuroses diarrhea, but a shared experience. Dr. X listened, nodding her head along with each of my concerns.

“Mrs. Nigmond, I think you have a beautiful face, but I totally understand wanting to make a few adjustments if that will help you feel better.”

She was just being polite, I thought. But maybe she saw what I did; that my husband had consumed me, taking everything he deemed useful, and what sat before her was the leftovers. I wanted to be somebody else and so I had Dr. X create an illusion with her magical wand (needles).

A few adjustments spiraled, some would say, out of control. For 11 years, I made my journey to the plastic surgeon’s office every three months for a tweak in the forehead, a little prick around the eyes, and some tiny stabs around the mouth. I had begun to see the injections and feel bursts of happiness, which only reinforced my choice. Confirmation bias? Sure.

And so, when John said, “You have a naturally beautiful face,” it startled me. It was the one sentence I’d longed to hear, though I never realized how much. I felt trapped in a cycle with no way out; as if I had forgotten what it was to be gloriously human. Most of my childhood was spent with my feet soaking in the Rivanna River, wondering at the soft ferns that unfurled and lined the banks. I’d often sneak out onto the roof to smell the air and guess what weather was coming. There was so much joy in playing in the woods under the trees only to hear leaves crunch beneath my feet a season later. Now, I had been divorced for years and in, what I felt was, a safe and healthy relationship. John’s words prompted me to wonder about my natural state and if that had been the version of myself that I liked all along; the girl who was happily raised on dirt. I wanted to remember, what I perceived, as a simpler and happier version of myself. Wasn’t I happier as a river creature that ran barefoot and wild instead of this version I had constructed from pain? Wasn’t I fooling myself into thinking that being pretty is being happy? I got off the hamster wheel and canceled my next appointment with Dr. X and committed to seeing if my old face was worth making a reappearance. I would wait 30 days past my due date to decide if Botox paralyzed my face and my pain.

There are two types of Botox users: liars and above-board. I can’t confirm that Jennifer Lopez uses only her JLO Beauty product line, but that’s what she wants us to believe despite her frozen eyebrows. She wrote, “For the 500 millionth time . . . I have never done Botox or any injectables or surgery!! Just sayin’. Get you some JLO BEAUTY and feel beautiful in your own skin!!” Then there’s my friend Ana, who allegedly uses Botox for medical purposes.

“Ana, you look amazing! What did you do to your face” I asked.

“Oh, it’s just a side effect from my treatments,” she sheepishly responded.

“Ana, what treatment makes you look like you’re entering a beauty competition, and can I have that disease, please.”

“Oh, I get these terrible migraines from TMJ. Apparently, I’ve been grinding my teeth at night, so my doctor prescribed me Botox for my jaw and forehead. It’s working so well!”

I stared at Ana, whose face could still look guilty despite being unable to move. Unlike Ana, I’m reasonably confident my Botox-free time will be perfectly fine. It’s not like I’m addicted to it. I can use contour and makeup to hide my age. There’s nothing more youthful than a bright undereye. I spent hours researching “concealer for old eyes” and purchased “Bright Future Gel Serum Under Eye Concealer,” which promises a lot in its name.

At the beginning of detox, I tried on denial. There’s nothing wrong with Botox; maybe detoxing suggests there is. Perhaps I shouldn’t do this and take a stand against judgmental people. They just don’t want me to be wrinkle-free. Plenty of women use it. In 2019, Botox treatments totaled 1.7 billion dollars in revenue for Allergan, the leading cosmetic pharmaceutical company. Since my first treatment, several other companies popped up to compete, like Dysport, Xeomin, Jeauveau, and the new longer-lasting Daxxify. According to the American Society of Plastic Surgeons 2020 report, over 15.5 million cosmetic procedures were done in the United States, with Botox being the front-runner at 4.4 million procedures and 3.4 million for injectables. Therefore, if everyone is injecting, it can’t be stigmatized.

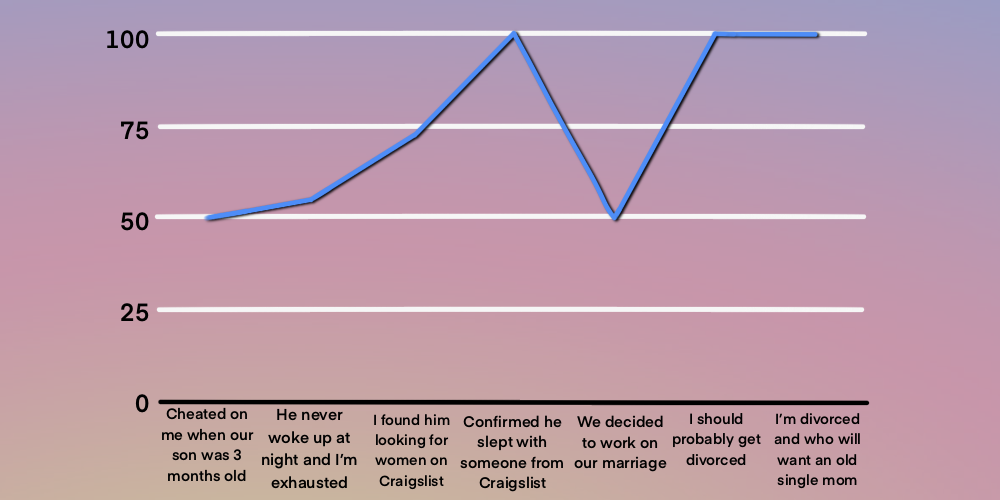

Post-denial reflection brought a highly biased chart based on life events with my (now ex) husband and units of Botox used.

To deflect the uncomfortable feelings (as seen above), I will blame social media and their continued portrayal of unattainable and unrealistic beauty standards. Last year, Jia Tolentino’s New Yorker article The Age of Instagram Face investigated what she described as “what seems likely to be one of the oddest legacies of our rapidly expiring decade: the gradual emergence, among professionally beautiful women, of a single, cyborgian face” who “Looks as if it’s taken half a Klonopin and is considering asking you for a private-jet ride to Coachella.” She’s not wrong. One scroll down the Instagram lane will teach you about the signature “five-point lift” that gives each face a more youthful appearance. Tolentino wrote, “I think ninety-five percent of the most-followed people on Instagram use FaceTune, easily,” a special filter that will show users what a face with Botox and fillers could look like. There’s nothing wrong with wanting to fit in, right? Wanting to belong can be traced back to our hunter/gatherer ancestors who foraged for botulism and glycolic acid.

About halfway into my detox period, I happily convinced myself that Botox is an addiction. Clearly, it meets Merriam-Webster’s definition: “a compulsive, chronic, physiological or psychological need for a habit-forming substance, behavior, or activity.” Therefore, the new feelings of disgust arising from forehead movement are my illness, and I don’t believe that it’s my fault.

The following is a list of skincare products I acquired during the 30-day detox in an effort to maintain my face: La Roche-Posay Hydrating Gentle Cleanser, Rosacea Care WillowHerb Serum with Vitamin K, Sunday Riley Auto Correct Brightening and Depuffing Eye Contour Cream, SkinCeuticals Phyto Corrective Gel, Cetaphil Hydrating Eye Gel-Cream, Juno 2% Caffeine Energizing Serum, Juno 2% Hyaluronic Acid Serum, SkinCeuticals C E Ferulic, Elta MD Broad Spectrum SPF, First Aid Beauty Eye Duty Remedy, SkinMedica Instant Bright, SkinCeuticals Antioxidant Lip Repair, and the holy grail, 0.05% Tretinoin Cream.

Running out of money, I called a friend who referred me to Mary Feamster, an LPC with over ten years of experience specializing in depression, anxiety, and eating disorders. Mary is well-spoken with a kind voice who lets me know she doesn’t see injectable cosmetic treatments as an addiction since “there is no chemical dependency. This is about body dysmorphia.” And like a movie reel, I see myself sitting in front of my vanity one morning after the other and recall the inner lady monologue. She says things like, “Check your forehead. Can it move?” “Hi, you almost look good enough to visit your grandmother,” “Congratulations on finding a bra to fit those knockers,” and “If you put a little more filler along the jawline, your husband might think you look like that girl from the craigslist ad.”

Mary goes on, “I’m looking for an unstable perception of how someone perceives themselves, a preoccupation, and something about it has to be disruptive to relationships or desired activities for it to be beyond common insecurity and really classify as body dysmorphia. A lot of people I see are not able to look in the mirror and have a stable idea of what they look like.” I ponder how any woman can feel stable about their appearance in the face of social media and cultural pressures.

During the brief silence of the interview, I realize there’s nothing stable about how my face appears to me. It had morphed from a mildly concerned youth to an obsessive staring contest with the mirror. The woman who stared back at me had once gotten home from an HIV test to make sure her husband’s forgetfulness didn’t have long-term consequences. After the incident, I’d push my cheeks up a little, raise my eyebrows with my fingers, and stare at the open pores almost nightly. In the quiet of our phone call, it was clear these obsessive feelings subsided after visiting Dr. X, but maybe a face isn’t silly putty you can stretch over bones.

Mary spoke a lot about obsessive use and compulsion. I ask what might qualify as obsessive use of cosmetic injectables.

“My experience is from my friends. The look they’re going for no one will even notice. They want it to be imperceptible. It fills and softens the lines. It gentles the aging process. Obsessive use would be somebody who is repeatedly modifying their appearance and then modifying their appearance more or somebody who would really struggle if, for some reason, they weren’t able to access it as frequently as they want to. It would be a huge difference in their appearance or disrupt the way they’re seen.”

I thought about what else I would have purchased and done had I not had so much cosmetic surgery. What would I spend my money on that might have been better? I’m a little ashamed of my own vanity and soon realize it’s more than that. It’s admitting that I was jealous of my beautiful sister. It’s acknowledging that motherhood permanently changed my body even if baby laughs are worth undereye circles and widened hips. It’s speaking my marital truth, that his infidelity broke my heart and vaporized whatever self-esteem my fragile new mom body had left. How I tried to morph into my husband’s porn history or my Instagram feed with each injection and scalpel. It’s taking responsibility for the pieces of myself I cut, sucked out, or filled. I wanted to once again adorn myself with honeysuckle crowns and dandelion rings, filling my time with observing the aging trees, not my face.

At the end of thirty days, my face still doesn’t have full movement. I sat at the mirror for the nightly staring competition and think about what Mary had said about recovery. Recovery doesn’t always look like acceptance. She explained that recovery sometimes looks like noticing your negative thoughts and sitting uncomfortably until they become neutral.•