The Parson Weems moment, the young-Washington-chopping-down-the-cherry-tree moment, in the accepted mythology of George Herman “Babe” Ruth involves a kindly mentor who first spots the hint of deity under the hardscrabble-boy exterior. It was Xaverian Brother Mathias at Baltimore’s St. Mary’s Industrial School for Boys who first took Ruth into gentle tutelage in the art and science of baseball. There are a few persistent apocryphal tales from those years: tales of the teenage Babe beginning to display the eye and reflexes that would one day make him one of baseball’s most underestimated pitchers and the sheer hitting power that would earn him immortality as the Wazir of Wham.

It’s a familiar device, these Parson Weems stories. They grow up entwined in the facts of their subjects’ biographies, covering the bare dates and facts with a green and shifting foliage of folklore.

No other figure from the world of 20th-century sports equals Babe Ruth’s folklore status — with only one exception: Muhammad Ali. The self-proclaimed “greatest,” the heavyweight champion boxer who taunted his opponents, sang his own praises, and by turns charmed and infuriated the world, had his own Parson Weems moment, or rather a one-two combination of them, and fittingly, it was a combination of outrage and showmanship — and the Parson was a cop.

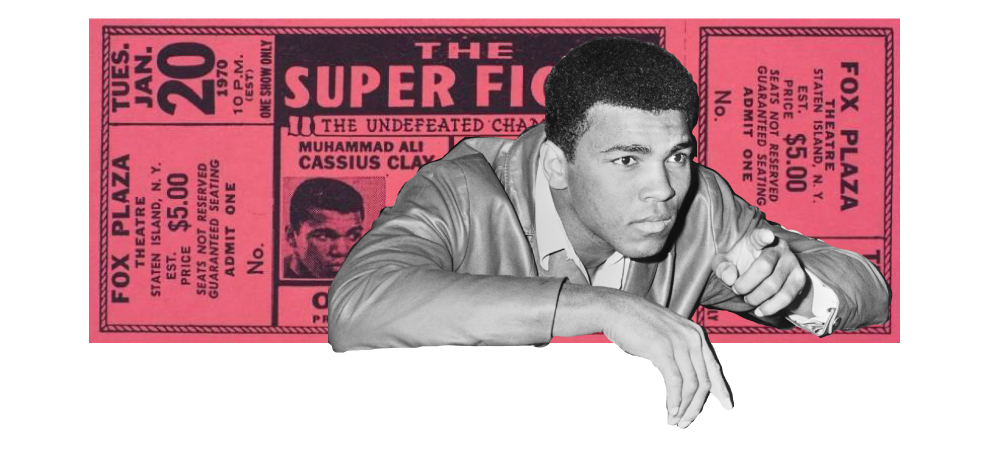

The story — retold with lean, friendly intensity at the beginning of Jonathan Eig’s fantastic new biography of Ali — happens when 12-year-old Cassius Clay (Ali’s birth name, which he later changed when he converted to Islam) had his bicycle stolen. Infuriated, he reported it to Louisville patrolman Joe Martin, who also happened to be a part-time boxing coach. Hearing the boy’s angry threats about what he’ll do to the thief, Martin asked if he knew how to fight. Martin also produced a local boxing TV show called Tomorrow’s Champions. And the combination — the invigorating physical puzzle of boxing and the allure of an audience to watch him do it — was the making of Cassius Clay.

The life that followed from that modest start (How many angry boys did Joe Martin mentor? How many future auto mechanics made brief appearances on Tomorrow’s Champions?) has been written in parts many times, taking Ali from his birth in January of 1942 in Louisville, Kentucky, through his incredible boxing career — one famous bout after another (“The Thrilla in Manila,” “The Rumble in the Jungle,” etc.), all the heavyweight championships, that electric, unpredictable style in the ring — through his conversion to Islam and refusal to fight in the Vietnam War, through the loss of his titles and the long legal battle to win them back, through his epic fights with Joe Frazier and George Foreman, and his many marriages, and his skyrocketing celebrity, and his long post-boxing career as a political activist and charity icon, and, as he gradually withdrew from public life, a high-profile face of Parkinson’s, the disease that would gradually stiffen this icon of lightning mobility into a slow, expressionless figure in his last years.

Eig’s is the latest, the longest, and by a wide margin the best account of Ali’s life. He tirelessly interviews everybody connected to Ali’s life — the opponents, the surviving wives, the managers, the sportswriters, and hundreds of others — and he combs through sources no previous writer has had access to: Justice Department files, FBI reports, and dozens of hours of taped interviews. He takes this vast amount of new information and fashions it into an incredible work of biography, a work that manages to be both fiercely partisan and very nearly completely objective. Eig recounts every delusional semi-comeback, every piece of childish callousness (readers will quickly lose count of how many mistresses Ali had, and they’ll have the strong impression Ali lost count too), every maddening character flaw, and — no small thing, in fact a lasting impression from the book — every calculated cruelty to his opponents in the ring (it should go without saying that heavyweight boxers cannot be nice when they’re on the clock, but the reality nevertheless feels jarring in Ali’s case).

And yet there’s never any doubt that Eig is on Ali’s side in the vague contest biographers often wage between their subject and posterity. As Ali was defiant, saying: “I am America. I am the part you won’t recognize. But get used to me. Black, confident, cocky; my name, not yours; my religion, not yours; my goals, my own; get used to me,” so too Eig is defiant, pushing back against the eulogies that claimed Ali had transcended race: “He didn’t overcome race. He didn’t overcome racism. He called it out. He faced it down. He refuted it. He insisted that racism shaped our notions of race, that it was never the other way around.”

The stirring, defiant tone of much of this is one of the signals that Eig is, in his own way, perfectly comfortable with Parson Weems-style mythmaking about his subject. If so, it’s a natural choice — indeed, it’s one that Ali himself took even from the beginning of a career that always mixed fantasy and reality. When torrential rains closed in on Zaire immediately after Ali’s “Rumble in the Jungle” against George Foreman to reclaim the heavyweight title in 1974, Ali claimed he personally held the rain back until after his victory.

He laughed, but Eig is alive, here and throughout the book, to the storyteller’s ways Ali was inserting himself into the national mythology. “With his victory over the mighty Foreman, the Ali myth grew again,” Eig writes. “He was John Henry hammering on the mountain but greater, because Ali had hammered over and over through the years — hammered on Liston, hammered on Patterson, hammered on white reporters who told him to shut up and box, hammered on LBJ, on Nixon, on the US Supreme Court, on Norton, on Frazier, and now on big, bad George Foreman.”

Ali spent half of his life sick and declining in health, and Eig invokes the shadow of that early in his book, quoting hammer-fisted boxer Sonny Liston talking about how the human brain rests in a series of “little cups.” When a fighter takes a “terrible shot,” the brain flops out of the cups and must settle back into them. “But if this happens enough times,” Liston says, “or sometimes even once if the shot’s hard enough, the brain don’t settle back right in them cups, and that’s when you start needin’ other people to help you get around.” This was the exact fate that awaited Ali; Eig estimates that he took roughly 200,000 punches in the course of his career.

And yet, Ali: A Life is the furthest thing imaginable from an autopsy; the book surges with life. Eig dives into every controversy, every questionable call in the ring and every picked fight — worthy and unworthy — outside the ring, and every larger implication of Ali’s life, most of which, for Eig, have a lot more to do with race than with boxing. It’s an amazing three-dimensional performance of a biography, and it’s lifted up at all times by Ali’s own personality, the outsized nature of the friendly man who bragged that he was so mean he made medicine sick. As Eig simply puts it: “Bitterness and cynicism never touched him.” •

All artwork by Emily Anderson.