The best American political book of all time is a product of bipartisanship. That in itself might seem implausible. The word “bipartisan report” is liable to trigger a panic response among those who associate the “B-word” with long-winded, superannuated statesmen and “thought leaders” who are even longer of wind. A bipartisan book written by authors from different ends of the political spectrum promises a combination of bloviation and blather.

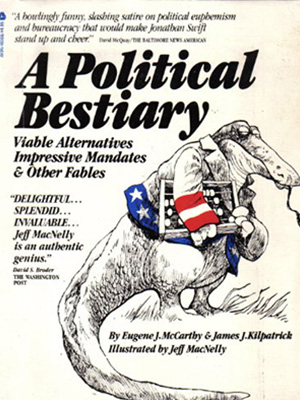

But I’m serious. The best American political book is A Political Bestiary: Viable Alternatives, Impressive Mandates, and Other Fables, published in 1978 by McGraw-Hill and co-authored by former Minnesota Senator Eugene J. McCarthy, conservative columnist James J. Kilpatrick, and illustrated by Jeff MacNelly.

McCarthy, who died in 2005, is best remembered for his help driving Lyndon Johnson out of the presidential race in 1968, thanks to his strong showing in early presidential primaries that year. “Be Clean For Gene!” was the advice to young members of the anti-Vietnam War movement who sought to avoid being dismissed as countercultural hippies.

Kilpatrick, who passed away in 2010, came from the far right. In the 1950s and 1960s, Kilpatrick made a name for himself as a fiery defender of Southern segregation as an editor at Virginia’s The Richmond News Leader. Following the Civil Rights Revolution, he shifted from defending white supremacy overtly to more conventional small-government conservatism. For nearly a decade in the 1970s, on the TV newsmagazine 60 Minutes, he debated liberals Nicholas von Hoffman and Shana Alexander. A celebrated parody on Saturday Night Live had Dan Ackroyd on the right responding to his liberal debating partner Jane Curtin: “Jane, you ignorant slut.”

The modern equivalent, then, would be a book written by Bernie Sanders and Patrick Buchanan. The unlikely duo of McCarthy and Kilpatrick produced a masterpiece of droll whimsy, using the medieval genre of the bestiary.

The mock-scientific tone is set by the first entry, “The Mandate”:

Mandates comes in as many varieties as finches, warblers, sparrows, and Southern politicians. They are generally divided into Greater Mandates and Lesser Mandates . . . Lesser Mandates are more difficult to find, even though they come in many sizes and forms. Highly sensitive Presidents and other elected officeholders rarely perceive a Slim Mandate. Political columnists, however, regularly confirm valid sightings.

Then there is the Gobbledegook:

Of all the creatures catalogued in this Bestiary, none is more familiar, none more widely distributed in North America, than the Gobbledegook . . . He has the gaudy tail of a peacock, the impenetrable hide of the armadillo, the windy inflatability of the blowfish . . . In the foggy world of the Gobbledegook, a janitor becomes a material waste disposal engineer and a school bus in Texas a motorized attendance module. Here meaningful events impact; when they do not impact, they interact; sometimes they interface horizontally in structural implementation.

Since the book was published, the Gobbledegook has speciated into new forms and expanded its habitat.

Among the delights of A Political Bestiary are the cross-references among articles, as in a genuine encyclopedia:

The Consensus also is like the Mandate. It can be compared to a Gathering Momentum that has not yet started to move. It has some of the attributes of the Aura. But no one of these — the Mandate, the Momentum, or the Aura — can fairly be said to be like a Consensus.

A few of the entries, topical in the 1970s, are dated now. Galloping Inflation is one. Another is the Last Priority:

Priorities once existed in great numbers, sizes, and varieties. They ranged over great areas of the world . . . Gradually they moved toward extinction, like ostriches, passenger pigeons, buffalo and an honest martini.

Now only one Priority remains. This is the Last Priority, identified by President Carter. After it goes, there will be no more Priorities.

Jeff MacNelly (1947-2000), the Pulitzer Prize-winning cartoonist who created the comic strip Shoe, was chosen to illustrate A Political Bestiary. Even Homer nods, and MacNelly’s imaginary beasts are not always as inspired as the passages they illustrate. For example, the Impasse is a moose wearing cleats. Even less imaginative is the Tight Budget, a hippopotamus in a corset, the Bloated Bureaucracy, a fat fish, and the Dilemma, a kind of antelope.

But at his best, MacNelly’s pictures match the wit of the descriptions. The “economic indicators” are prairie dogs, popping up from their holes in the ground. One holds an umbrella, another wears a scarf, and a third wears spectacles while gnawing on a sales chart.

The most memorable illustration in A Political Bestiary portrays the “Qualms.” According to Kilpatrick and McCarthy:

While they are not threatening, they are disturbing . . . Like Trepidations, Qualms will gather at the far end of a bar. From such a distance, they cast accusing glances. Their eyes are large, dark, and unblinking. They give voice with a gentle, persistent bleat.

Inspired by a line in the text, MacNelly’s Qualms are furry, sad-looking creatures with enormous eyes, like tarsiers, staring across a bar in a saloon. Since I came across the book three decades ago, this creepy image has never left my mind.

A Political Bestiary is out of print. Some publisher should republish it — perhaps with new illustrations. In the meantime, if you can find a used copy, I think you will share my judgment that it is the finest product of bipartisan collaboration ever produced by an American politician and an American pundit. Which, I’m sure McCarthy and Kilpatrick would have agreed, is not saying much. •