It was right there, a bit of boilerplate I had slugged in, due to be cut in the next draft: “In light of recent events . . .” I was hundreds of words into sifting the issues that arise when white rap fans use the N-word, knowing that whatever I came up with would be read during one of the most publicly race-conscious moments of recent history. But after Alton Sterling and Philando Castile were shot and killed by cops, many of those words I’d written wanted to twist, or invert entirely. By revising the first sentence, I found a twist.

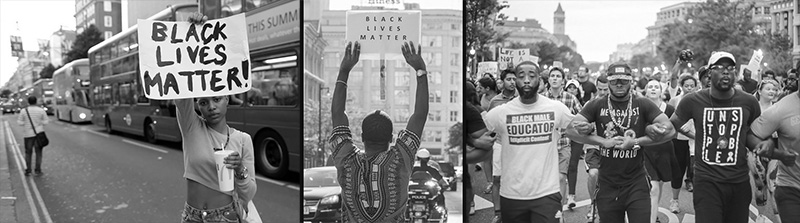

“Recent events” are exactly what the recent police murders are not. These acts of violence are ongoing events, or, more unstopped than ongoing. The accurate rhetorical phrase to open any revision now could be “In light of reality,” or simply “In light of the unchanging now,” and then back to your regularly scheduled content.

The N-word has that quality of being unstopped, even if its social deployment has changed. The fact that one community reclaiming the word has led to another community hearing the word more often does not strip the word of its original purpose, nor detach it from the process of white supremacy that produced the word. As a slow but real discussion of white supremacy has begun on talk shows and in social media vortices, the N-word finds itself recharged. It is not often you can say “tool of the oppressor” and be both accurate and understated, but that is the N-word. The word itself is the act of human devaluing that legal and social change sought to redress but apparently did not.

So why would so many people throw themselves into the fan blades with this word? The word has taken on many different valences when used between various cohorts that, as a social interaction, it is too broad for the scope of this brief investigation. There is only one question at play: why would white people who might not imagine saying the N-word out loud, end up singing that word? In “Lift Me Up,” Vince Staples isolates the moment: “All these white folks chanting when I asked them ‘Where my niggas at?’ Going crazy, got me going crazy — I can’t get with that. Wonder if they know I know they won’t go where we kick it at? Ho, this shit ain’t Gryffindor — we really killing, kicking doors.”

In “Lift Me Up,” the N-word defines a cohort not ready to collaborate with the people that stuck them with the word in the first place. Staples votes against the idea that consciousness can be borrowed by borrowing a word. Slurs like the N-word are sometimes reclaimed and repurposed — “bitch,” “redneck” and “queer” have all increased in semiotic density over time — but the N-word has a unique polarity. As much as it can be a term of solidarity in certain situations, it can’t lose its original toxicity until an original event is acknowledged. And America has never pulled that off. There’s never been an effective renunciation of white supremacy, likely because it is both amorphous and embedded. Many discussions of white supremacy simply end when they begin — “There is no such thing!” If America had a consciousness of its own legacy that resembled something like Germany’s ongoing acknowledgement of the Holocaust, a lot of words could change as suggested by Ta-Nehisi Coates in his landmark 2014 piece. Until then, the N-word is stalled, reclaimed but not neutered. In some ways, how it fluxes, as a word, mimics the unstable terms of personhood and civic rights in America. At times, those rights have seemed arbitrary; now, these rights seem easily predictable in their recurring absence.

So how did we get all the way to the call-and-response moment Staples raps about? Unlike literature or film or theater, music is what scholar Thomas Turino called a “participatory performance” in Music As Social Life (2008).

A primary distinguishing feature of participatory performance is that there are no artist-audience distinctions. Deeply participatory events are founded on an ethos that holds that everyone can, and in fact should, participate in the sound and motion of the performance. Such events are framed as interactive social occasions; people attending know in advance know that music and dance will be central activities and that they will be expected to join in if they attend.

Turino is talking specifically about musical performances he witnessed in Zimbabwe and Peru, but his theory works equally well for live pop events. Cue “Lift Me Up.” In fact, at a recent Staples in Los Angeles, Staples repeatedly criticized the crowd for not being participatory enough, mocking them for looking like people with day jobs and complaining about the half-full room. The white rap fan is in a bind here when it comes to her perceived obligations. Even if she took the infamous advice of Ego Trip’s editors, and shouted “ninja” rather than the N-word, the person standing next to her would likely not know the difference.

When Staples mentions J.K. Rowling’s Gryffindor, he’s indirectly acknowledging how music, like other art, works out themes through fantasy. Music allows any number of demons to be worked out in the virtual plane, and musical fandom can drift through admiration, disorientation, and wonder without ever hitting full-on identification. Some listeners never put themselves in an artist’s shoes, but hip-hop culture has become so prevalent in America that hero worship of MCs is almost inevitable. While raising two teenage boys in New York City, there was no contest when it came to a cultural consensus. Whatever loonball music I played at home was ignored; the boys came home every day listening to rap, discussing rap. My older son didn’t even hear classic rock, not in any way that made an impression, until he went to college. It is one thing to imagine wielding the hammer of the gods in Valhalla, a scenario not likely to upset any gods or Valhallians, and another to imagine yourself in a specific social setting with very specific affinities, and to say that out loud.

A hopeful type might be able to imagine an America that begins to collectively acknowledge, in less than a 100 years, the social conditions that created the N-word and that allow it to exist still, in its weaponized state. A practical person would encourage non-POC rap fans to treat MCs like writers, just to reduce the amount of symbolic noise. People don’t generally feel the need to chant along with James Baldwin’s The Fire Next Time while reading. Listening can be an active way of participating, and it is possibly the most important act right now. •

Feature image Schoolboy Q and Kendrick Lamar courtesy of Darnelle Hailey via Flickr (Creative Commons).