It’s not too much to say that Vincent Van Gogh was haunted from the day he was born. His dour Dutch Protestant parents, his father from a long line of ministers, named him Vincent after the previous child who had eerily died exactly a year before the painter’s birth on March 30, 1853. Born as he was under the feisty sign of Aries, those fire sign characteristics fit the passionate, impulsive, irascible fellow quite well. I like the curt, slashing way that he signed his paintings using his first name only; it’s simultaneously cocky and intimate. And if there was ever a great painter who should be referred to by a first name basis, then it’s surely Vincent Van Gogh.

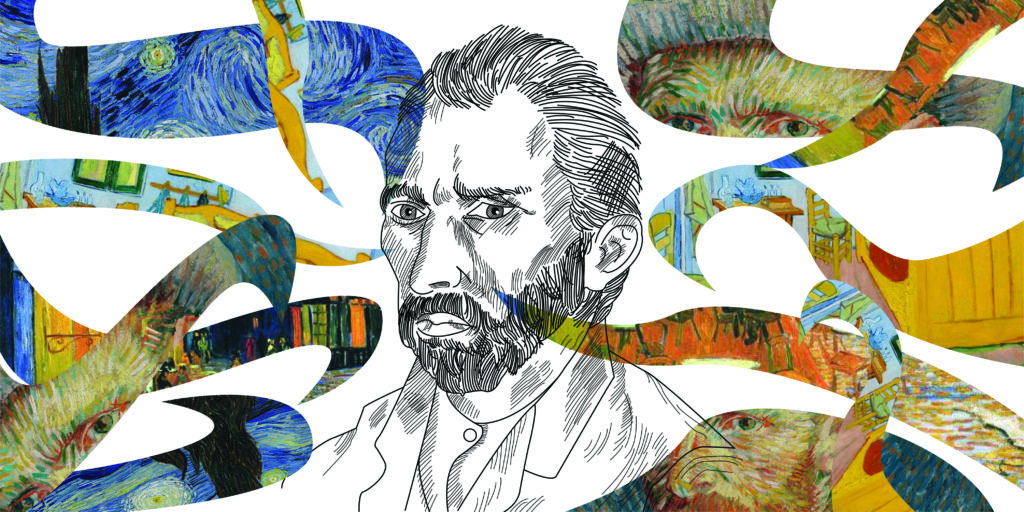

Over a hundred years later, the painter who is infamously (and inaccurately) reputed to have never sold more than one painting and denied the recognition is now a household name. We just can’t stop talking about him. His works go for gazillions at auctions. There’s a traveling interactive exhibit called Van Gogh: The Immersive Experience where people pay to sit amid animated reproductions of his work (about which one critic cracked wise: “what’s next, staring at a Warhol for seven hours?”). There’s a lovely, large, and popular museum solely dedicated to his work in Amsterdam. You can see tribute graffiti and murals painted on the sides of buildings all over the world. He’s been the subject of biopics done by big-name directors like Robert Altman and Julian Schnabel, with uneven results. You can buy all kinds of knick-knacks — t-shirts, posters, mouse pads, etc. — with his face or his paintings emblazoned across them. Everyone instantly knows paintings like Starry Night whether they’re particularly interested in art or not. Tupac Shakur wrote an appreciative poem about Van Gogh while behind bars, seeing him as a fellow mercurial artist persecuted by an unsympathetic world.

It’s fitting that such a peripatetic fellow should be the subject of a book entitled In Search of Van Gogh, which documents his incessant traveling through quite a few locations within several countries. Beginning in his hometown in the Netherlands through time spent in The Hague, Amsterdam, London, Brussels, and especially France, starting from Paris and then migrating deeper south, into the intense light and vivid colors of Arles and Provence. Restless, a fast walker and relentless talker, Vincent was never capable of settling anywhere for very long.

As a young man, Vincent tried to be ordained as a minister, which didn’t work out too well, settling on being an amateur preacher in coal mining communities. He seemed to find it hard to get along with anyone, despite his best intentions. As far as religion goes, his motivations certainly seem genuine, although the tone of his evangelism contains more heat than light — one gets the feeling that he knows the words but can’t sing the tune, so to speak. There is always (com)passion flowing through him in abundance, though he lacks the profound patience and stillness required of a true holy man. Not finding the existential solace he needed in the church, Vincent spent the rest of his life religiously devoted to his art. It’s not for nothing that he painted himself as a Zen monk, pale and bald with piercing eyes and rigid facial expression while exchanging portraits with Gauguin. Gauguin preferred to depict himself as Jean Valjean, the reformed convict from Les Miserables.

Some say Vincent’s first real masterpiece is The Potato Eaters which, unfortunately, is not given the size on the page it deserves. I used to be weirded out by those grotesque gremlin-like creatures gathered around the pathetic meal in some hovel until I actually saw it in person in Amsterdam. This affectionate but humble family has been gnarled by years of arduous, inhumane toil. Especially with the Rembrandt-like warm lighting and seemingly subterranean setting, they look fashioned from the very earth itself. Vincent never lost his admiration for Millet, the French Realist painter who championed peasant life and work. He spent serious time with the local miners both above and below ground and wrote observantly about their lot. It’s an important part of his many engaging and powerful letters to his long-suffering brother Theo, who tirelessly kept his turbulent brother alive financially and emotionally.

Still Life with Bible, circa 1885, serves as the coda for Vincent’s explicitly religious phase. His recently deceased father’s formidable Bible, massive and clunky, dominates the stark black frame though the words of scripture are hastily blurred out. Beneath it is a small, yellowed, but well-thumbed copy of Emile Zola’s naturalist novel Le Joi de Vivre, a story which is apparently much more depressing than the title would suggest. The solemn mood, with a guttering solitary candle, captures what it feels like to have left faith behind yet remaining doubtful about the alluring world beyond the church. Soon Vincent will bitterly write “let them reason, those cold theologians.”

If it’s life that the young Vincent was after, he certainly got more than his share of it. In some ways, too much life was kind of his whole problem. Maybe it wasn’t the best idea to intend to marry Sien Hoornick, a pregnant alcoholic prostitute. Noble intentions aside, he really didn’t need to take such offense at his family’s criticism. His sketch Sorrow is a quietly moving portrait of her, slumped over with wrinkled breasts and her tangled head hidden in her weak arms.

Pair this with Old Man in Sorrow a few years later where the subject sits alone in his chair grinding his knuckles into his eyes, stooped over amid waves of blue. And it’s subtitled “at eternity’s gate” because of course it is. In Wheatfield with Crows, one of his later works, you can feel the chill of the country wind as you watch those haunting little crows taking off into the darkening sky above the billowing wheatfield, the beaten path ahead not stretching out for very long. Nobody does weltschmerz quite like Van Gogh.

Yet amid all the sorrow and suffering let’s not forget how alive his use of color really is. In Search of Van Gogh does give some page-sized appreciation to some of his most vibrant work. As a good Protestant lad, Vincent worked very hard to earn the grace of technique. What Vincent can really get across is the sense of the hidden life of a person or an object or landscape, the energy trapped within humble form. Think of all those marvelous sunflowers, bursting with yellow, curling upwards towards the light. Or the piquant way the bookish Madame Ginoux gazes into space, a smile curling in the corner of her mouth. Consider that lonely, lovely lily cast aside amid a swarm of blue stalks.

The vibrating flow of the sky in “Starry Night” may have had something to do with his recent stint in an asylum, but contrary to what some sentimentalists assume, Vincent’s vision persisted despite his sea of troubles and not because of them. The book perceptively highlights how his understanding of the sky was probably influenced by reading about new developments in astronomy. Everything is always surging in Van Gogh’s world; the mood, the tone, the sheer vibration of feeling — that’s the stuff of art, which is to say of life. It’s what we keep coming back for.

It’s too bad that we don’t have many letters from Vincent’s productive two-year spell in Paris. Living with Theo, his best friend and primary interlocutor, meant he didn’t need to write him any letters. It would have been illuminating to hear a firsthand account of his time in that legendary mecca of artists, soaking up the fertile aesthetic atmosphere at all the galleries and cafes, getting into pointillism and Japanese prints, hanging out with the likes of Renoir, Cezanne, and Toulouse Lautrec, who did an affectionately colorful portrait of him in pencil.

We do have some Parisian self-portraits. In the first, with one of his many pipes, he has a corpselike pallor. He’s not as old or as experienced as he portrays himself to be, and it doesn’t matter. He has the face of a man who has seen things. Those eyes glower apprehensively at you. There’s also a self-portrait from the fall of 1887 where he looks like he’s being electrocuted with color. Those piercing, beady blue eyes don’t start to settle into something approaching normality until he leaves Paris, in the summer of 1889. Then he really starts to fill in the center of the frame of his self-portraits, posed confidently as plumes of blue and black zig-zag all around him like invisible applause.

Then we encounter his febrile time in the south of France, which he adores (“I’ve never had such good fortune; nature here is extraordinarily beautiful”) and in which he goes progressively madder. Quickly freaking out Gauguin, ruining his plans for an artist’s commune in what he dubbed The Yellow House, and there’s the infamous unpleasant episode with the ear. As he recuperates in a mental institution, he’s luckily watched over by an appreciative doctor who sees that painting soothes him. You’ve got to hand it to Vincent, even in his darkest hours he doesn’t complain or blame others very much for his suffering. He wills himself to keep it together, and he churns out one masterpiece after another. He gets the work done, and splendidly, even when everything else is falling apart.

Trouble always started when the world was, as they say, too much with him. All that nervous energy always coursing through his canvases might have wound the human being painting them too tight. Reading the letters, it’s not that Vincent is a humorless grump, though he certainly isn’t what you would think of as cheerful. The multiple postscripts and run-on sentences can wear on you. Vincent is so wrapped up in his own internal dramas, anxieties, and ambitions that he simply doesn’t know how to relate to other people. When he says that he has no talent for dealing with people, you can believe him. Unless, of course, it’s on his own terms, aspects of his private seething cosmology. Vincent’s paintings give you a visceral sense of the internal life of things because he lived so close to the bone.

I once knew a woman who told the story of how when Vincent fell in love with his cousin he arrived at her parents’ house and demanded to see her. They tell him no. Lighting a candle, he insists on being able to see her for as long as he can hold his hand over the flame. This sounded romantic for about five minutes. It’s the kind of thing that you might see in a movie or in a novel but if it actually happened to you in real life you’d quite justifiably freak out. Surprisingly, it didn’t work out well for Vincent, either. Wanting something, especially very ardently, is nothing. What happens when you don’t get what you want shows you what you’re really made of.

When we think about the legend of Van Gogh, we should make a distinction between being self-involved, which he absolutely was, and being self-important, which he generally wasn’t. Vincent was a deeply literate man who read widely and fluently in several languages and was capable of earnest conversation and genuine humility. When he received praise from a respected critic a few months before he shot himself, he quietly declined it and encouraged the critic to look at the work of a now-forgotten painter named Monticelli instead.

There’s no doubt Vincent was mentally ill, probably what we would now call bipolar. He certainly needed to learn to relax a bit. Gauguin said that all he ever talked about was authors, which certainly isn’t the worst possible fault, but it’s further evidence of how thoroughly Vincent lived in his own head. The two short-term roommates offer a case study on the need for adjusting one’s attitude towards the world outside of your own head. Suave Gauguin knew his way around the brothels and bars that he and Vincent visited. He painted the proprietor of one affectionately, with warm colors and giving her a wry look. In contrast, Vincent depicts a smoky, eerie, Bermuda Triangle-like house of decadence and despair where men lose their souls.

It’s easy to over-sentimentalize Vincent as the lonely, misunderstood, tortured genius that he indeed was. He joins the ghostly company of Emily Dickinson, Nick Drake, Vivian Maier, and many others whose vision went unrecognized until long after they were gone. At times, it’s tempting to imagine ourselves in that number. Perhaps it’s a defense mechanism for our own private failures, procrastinations, and ambitions. Maybe someday, we tell ourselves, we’ll finally be recognized for what we imagine ourselves to be. Well, good luck with that: many are called but few are chosen.

One important factor is whether or not you’re willing to put the work in to be receptive and generous to the world whether it accepts you or not. You can bet your bottom dollar that all the greats we admire certainly did, whether or not it was easy. This vulnerable tenacity is what separates the local crank at the bar from the unheard visionary. You have to believe in the work, be open to what fuels it, and this Vincent certainly was. He gave his life to it. Maybe the muse doesn’t reward madness or suffering so much as persistence. The museum dedicated to him in old Amsterdam will display a great amount of pain and torment, but it will also tell you that those haunted wheatfields can be a symbol of the seasons of life, always beginning afresh, the rich earth turning over, new seeds beginning to take root. The scythe isn’t forever but maybe the paintbrush is.

I was moved when poor Theo, after years of being his exasperating older brother’s shoulder to cry on, informs Vincent that he and his wife Joanna Bonger (without whose dogged efforts there probably wouldn’t be a Van Gogh Museum at all) have named their newborn son after him. They tell him they’ve always admired his determination and talent. It’s a beautiful gesture after all the blood, sweat, and tears Uncle Vincent’s various moods have put them all through, letter by anguished letter, year after furious year. And now we can comfortably reap the benefits that poor Vincent never could, sweating out his lonesome visions on the blank canvas, hoping someday that someone will try to see him in full. •