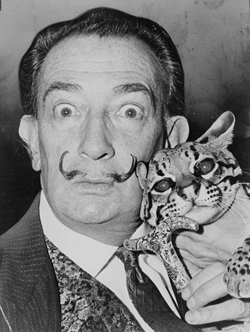

Salvador Dalí was skating on thin ice. It was a shtick and he was doing his shtick. He would open his eyes wide and give the patented Dalí stare. Surrealism. Granted, Andre Breton was never exactly a paragon of personal dignity but at least there was something at stake in the early days. By the end, Dalí was nothing but a parody of the thing he’d created of himself.

But it isn’t all crap, and that’s the revelation at the heart of the new exhibition “Dali: Painting & Film” (now leaving the Los Angeles County Museum of Art for St. Petersburg, Florida, and then MoMA this summer). Somewhere between the posing and the vamping and the recycling of tired imagery he created something. It was a new kind of landscape and, I think, a new kind of realism. The technique was relatively simple. He took the luminosity from some of the old masters, Caravaggio in particular. He was struck, I suspect, by the way that a painting like Caravaggio’s “The Conversion of Saint Paul” shimmers on the canvas and the way that the internal logic of the image lodges itself in the brain. Dalí was right to work in oil and he was not ashamed of gloss. His next step was to remove things. He took out most of the color palette so that when you think back to a Dalí painting you usually think of it as being gray. Gray, of course, is the color of memory. Next he took out most of the content, leaving a couple of objects shimmering there in the sea of gloss.

The result is images that are hard to get out of your mind even though they don’t mean anything and are never going to. And that’s why Dalí’s paintings are more interesting than the cliché of Surrealism. The stupid version of Surrealism is a series of simplistic reversals. Faced with sense, I give you nonsense. Faced with waking life, I give you dream life. Faced with rationality, I give you the absurd. Most of the time, Dalí seems to have agreed that this approach was sufficient. Thus the stares and the ridiculous mustache. But luckily, Dalí wasn’t interested in spending much time thinking about things. He was far more interested in plucking images out of his head and he had the skill to do them justice. The result is a Surrealism that is far more persistent in its troubling implications. Dalí’s landscapes aren’t good because they deny meaning or subvert it. They’re interesting because they sidle right up to meaning but refuse to deliver on anything specific. They have the lure of symbolism without the pay off. The symbols and images in Dalí’s paintings want to mean something. Instead, they linger in that area just before meaning, or off to the side of meaning. They are, in fact, dredged up both from his own memories and from the history of painting. For instance, he was always obsessed with Jean-François Millet’s painting “The Angelus.” But Dalí ignored the explicit meaning of the painting. He wasn’t interested in the religious background nor especially concerned with the contents of the prayer known as the Angelus.

Instead, Dalí was fascinated by the simple fact that the painting was lodged in his consciousness because he was surrounded with reproductions of the painting since childhood. As such it became a fetish object for him. He saw sex and death lurking in the shadows of the painting. Dalí’s attempt, in an incredibly boring book, to disclose the symbolic meaning of the painting is fairly tiresome and panders to the side of Surrealism that boils down to pop-Freudianism. Again, the man was no thinker. But his painting “Archaeological Reminiscence of Millet’s Angelus” is a typically successful Dalí landscape. He’s turned the figures of Millet’s Angelus into architectural ruins on one of his barren landscapes of dream and memory. It is as if he’s made literal the way those figures had become part of the architecture of his mind simply because they had worked their way inside him as a child. The painting, like most of Dalí’s better works, explores the chance memories and images that structure us despite our never having chosen them. And that is the deepest and most disturbing side of the Surrealist lesson. It’s not that everything we thought was rational we suddenly realize is irrational. It is that rationality itself is structured around a crazy mix of events and experiences that generate meaning but which we never fully understand as such. But because they are so important to who we are, they return in our memories again and again. Contrary to the official dogma of Surrealism, we do make sense of things, but we do so by working with the oddest of materials. We’re negotiating the world by weaving a web of meaning from chance happenings, things that just as well could have been otherwise. Surrealism, at its best, recognizes just how fragile is that web of meaning. If you step to the side of your experience for even the briefest moment you cannot come to any other conclusion than that it is a terribly strange thing indeed to be a human being.

When Dalí let himself go and let his undeniable painterly skill do its work on his new landscapes of the mind, he produced works that show us our own strangeness. I find “Moment of Transition” particularly haunting. It is the standard Dalí craggy dreamscape. The sky is a mix of the murk of memory, what may be a dust storm, and some cloudlike formations. A man sits in a covered wagon. A woman walks pointedly toward the wagon trailing a long ribbon. It’s a Western of sorts. She is walking from the dark side of the painting into the lighter side. Something will happen, but at the same time, there’s absolutely nowhere to go. • 4 January 2008