When I was a student at Northwestern University during the mid 1970s, my father visited Chicago for medical conferences a couple times a year. On these occasions, he would make it a point to treat me to dinner at a white tablecloth place downtown — usually $$$ in the AAA Tourbook. I would take the El down from Evanston. Dad and I would indulge in stylish 70s dishes like Steak Diane or Chicken Kiev. Shrimp cocktail first, of course. I was the envy of the girls in the dorm who were forced to fork their way through the mystery meat in the Willard Hall cafeteria.

My parents’ marriage had fallen into the dumpster at this point, and our father-daughter dinners felt vaguely like dates. I’d guide the conversation along a light path — my French and English classes (très boring to Dad), my job at the library (a little more interesting since it earned me pin money), and my volunteer work at NU Legal Aid (definitely helped me rule out law as a career). Avoiding the subject of Mom, Dad would update me about my brother, who was learning how to live an organized life at sleep-away military school, and my sister, apparently a normal high school senior: She went out on dates, talked on the phone a lot, and didn’t like homework. My father would remind me that I needed to slim down, said diet to commence directly following our splendid meal. Then he would bring up the dreaded topic of my post-college plans. Of this I had no solid notion, merely a vision of myself in Europe attending garden parties with famous literary types. I was careful to agree with Dad on all things. He had a famous temper, and you never knew how many cranks it would take to make him go jack-in-the-box. Two issues classically unhinged him: not getting his way and not receiving enthusiastic demonstrations of love from his children. Although he did not realize it, the jack-in-the-box thing could sometimes strain the quality of affection.

Now retired, my father was an extremely dedicated doctor and he often received notes of thanks — once even a live chicken — from his grateful patients. He studied voraciously, rose before dawn to make his hospital rounds, and with office hours and research meetings often did not arrive home until late at night. He loved golf, ice skated like a pro, considered himself a wine connoisseur and, when out to dinner with other couples, battled for the check. His taste in clothing ran from mod to odd: He grooved on bold colors and big stripes. Maybe it was the golfer in him; maybe it was the belated influence of the swinging London and Carnaby Street style. When it came to trends, our hometown of St. Louis lagged behind other cities; the 60s didn’t reach us until the 70s.

Clothes and appearance mattered a great deal to Dad. One of the worst fights my parents ever had erupted over a brand-new black-, brown-, and white-striped shirt that Dad wished to wear to a party. Mom said he looked like a clown or a carnival barker and wouldn’t let up on her criticism. A rampage resulted. My parents, now long divorced, were like two tornados loose in the house. Small wonder that Dad looked forward to business trips.

One night Dad called me at school to say that he was coming to town for a research conference and directed me to meet him at the Playboy Club on East Walton. “Someone at the meeting,” confided Dad, his voice thick with secrecy and excitement, “has a key to the Club. This is very VIP. Strictly big time. Only special people have keys to the Club.”

The Playboy Club! The hair on my unshaven legs hackled up. I was a budding feminist and hated Hugh Hefner with the best of them. He was a seedy old perv who reduced women to sex objects and peddled the myth of the modern liberated girl, on the Pill and ready to ball (that awful word from the 60s and 70s) with whomever, no regrets, no aftermath. Sure I knew Playboy. It arrived at our house in St. Louis every month like an evil period, its slick pages scattered with bare-breasted gals slithering around on silk sheets or, in the winter issues, lounging bare-cheeked before an open fire. Fantastic figures, no zits, no cellulite. Talk about making a woman feel embarrassed about herself by comparison.

I knew that the consequences of resistance would not be calm, but I sallied forth anyway. I was a college girl. I was a protester. I believed in speaking up for what I believed in.

“Dad, Hugh Hefner’s a male chauvinist pig and a creep. He makes me sick. I don’t want to go the Playboy Club.”

“Don’t worry,” said Dad humoring me. “Hefner won’t be there.”

“That’s not the point. The point is that Playboy exploits women. It’s against my principles to go there.” I knew I was turning the crank, but the faint hope flickered that Dad would see things my way.

Thankfully, the Playboy Clubs have gone the way of the powder-blue leisure suit and the eight-track tape. The last old-school American club closed in 1988, and the final international holdout in Manila mixed its last cocktail in 1991. In 2006 Hefner opened a new Playboy Club in Las Vegas, and I was hoping that what had happened in Vegas would stay in Vegas, but now there’s buzz about new clubs in Cancún and Miami. In any event, back in 1974 Playboy Clubs were a pasha-land for guys of a certain cast of mind, men who fancied themselves swingers even if they never really swung. The sales magic was in the tease. The turn-on was the fantasy, the promise of sex. And Bunnies had, er, strict rules of conduct. They were not allowed to date customers or, when serving drinks, heave their cleavage in a fellow’s face. To prevent such a spill, the girls had to perform a straight-backed, curtsey-like maneuver called the Bunny dip. Whatever. While other marketers were using sex to sell toothpaste and cars, Hefner was using sex to sell sex… and booze in the clubs and ad space in the magazine. Hefner’s marketing genius did not redeem him. My feminist sisters and I deplored everything Playboy. The whole concept degraded women. It was exploitative, objectifying, sexist, lookist.

My conversation with my father been taking place on the hall phone in my dorm, Chapin Hall, which happened to be an all-women’s residence. Normally, the girls gave whoever was on the phone a lot of space, but with “Playboy Club” and “Hugh Hefner” springing out of the conversation like champagne corks, I attracted a crowd, a sort of Greek chorus in bathrobes and curlers. Jan, always a cut up, made bunny ears behind Jill. Linda, the biggest women’s libber on campus, raised the power salute. Karen and Nancy listened as they munched from a freshly popped bowl of popcorn. I was militant to begin with, but the more the women watched, the more emphatic my advocacy became.

“Dad,” I tried to bargain, “why don’t you go to the Playboy Club with your friends, and I’ll meet you for dinner afterward.”

No dice. He wanted to introduce me to his conference friends. This made me feel like a specimen; furthermore I knew I was no match for their sons and daughters who were already in or headed for med school and law school and grad schools of various types. The conversation juggernauted on. I mentioned one more thing about feeling weird around the half-naked Bunnies, and Pop popped. I had flunked his test of love and loyalty; his inner King Lear sprang to the surface.

“I will NEVER ask you to meet me anywhere else again!” I could hear him slamming the top of his desk. “Goddamnit, stay in the dorm and do your homework.” A bruise spread through the air. My Greek chorus melted away.

My father paused. His anger required a second wind. “I pay a goddamn fortune to send you to Northwestern, and this is the thanks I get?” His voice was shaking with what I thought was rage, although it might have been something else, something more desperate. Then he fired his best shot. “You can pay your own way through college.”

My father knew that I wanted to stay in school more than anything else, and this was not the first time he had threatened to stop paying for Northwestern. So I caved and agreed to do the filial thing, if you can call a date with your father to the Playboy Club the filial thing. I was practical if nothing else.

I dressed in protest. This was not too difficult as I was cultivating the communist factory worker look at the time. I donned a shapeless polyester jumper the color of dead leaves, a yellow oxford shirt with stains on the frayed cuffs, black tights, and oxblood brogues, which I coveted for their strangeness and clunkiness. They were pretty much my usual clothes, but in a worse-than-usual combination. As I dressed, visions of Hugh Hefner bubbled in the alembic of my mind: a middle-aged man in his all-day pj’s always ready for a go-around with one of the nubiles, his hawkish male gaze smoldering over his pipe, on the lookout for fresh girl. Near at hand, a glass of Pepsi. There was only one way to deal with the situation; I would act as anthropologist. I would observe and report back to my cohorts. I thought of Gloria Steinem and her famous Playboy Club exposé.

The late spring sun still blazed as I emerged from the odorous El, and I found my way to 116 East Walton Street. A door Bunny let me into the club, and I was mildly surprised that she did. It took a while for my eyes to adjust to the gloom — for some reason the atmosphere felt draped in black crêpe. Every other person appeared to be smoking; I knew that I’d come back to the dorm hair and clothes reeking of cigs. The scents of booze and men’s cologne spiked the air, and the room bubbled with animated chatter like a house party. Friends were meeting friends. Alone and out of place, I felt more self-conscious than ever.

The room was furnished with upholstered square booths and dark wooden tables with wooden chairs. Everyone was drinking. No one was eating. Patrons, I understood, dined in restaurant rooms upstairs. I noticed a few groups of guys in their upper 20s, dateless but looking. For whom, I didn’t know. I saw very few single women, and I certainly didn’t count as game. Carrying a drink tray on which sat a stack of glass ashtrays, a voluptuous Bunny would sidle up to a stag table and welcome the men in a sultry voice. To impress her, the guys would try to outdo each other with displays of cool sexual charm, but behind the show of bravado I perceived shakiness and a sinking sense of unslakable desire.

In your dreams, fellas, I said to myself.

I’ll say one thing for the Bunnies, at least on the floor of the club, they did control the men.

But stag guys were only part of the mix. Among the patrons, I also spied older businessmen on the town and Midwestern guys with their dates, many of them regular gals in their office-worker skirts and blouses. Only one woman appeared the paragon of chic femininity. Slinky in a sleeveless black sheath, about thirty, she held a glass of white wine and inclined to her man. Near the bar perched a less glorious dame, feverish with blush-on, apparently snozzled; she seemed to scan the room for the date that might or might not be standing her up. This was not my scene. My scene was hairy, down-home, Chicago folkies in jeans.

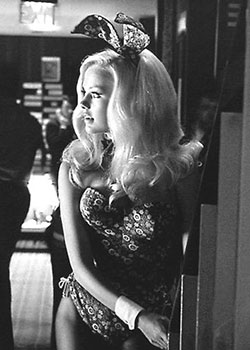

I saw far fewer Bunnies than I expected. Every so often, one would float by, drink tray in hand, cinched into her tiny-waisted satin corset, breasts pushed up so that she seemed to be carrying two cups of pudding on her chest. The Bunnies wore headbands with satin bunny ears, flesh-toned stockings, high-heeled pastel pumps with pointy toes, and that odd male tuxedo touch — bow ties and white cuffs with cufflinks. Sure enough on her rear, each girl sported a big poufy cottontail, like a giant powder puff. The Bunnies were pretty, the way cheerleaders and certain sorority girls were pretty. So there I stood, a groundhog among the Bunnies, a sack of potatoes in the confectionary. To the patrons, the Bunnies smiled their pressed-on smiles. Most appeared not to see me, though one cast me a suspicious eye. Like I might go Carrie Nation on the place or start a protest chant.

Drawn by the sound of jazz, I squeezed through the crowd to a little stage area where a black jazz trio — a drummer, a pianist, and a man on a upright bass — was playing “A Lot of Livin’ to Do.” I joined the small audience around the combo. Thank God, I thought, I could stand there and appreciate the music while waiting for Dad. After a couple songs, the small audience drifted away, but having nowhere to go I hung around watching the guys swing into “What Kind of Fool Am I” and then “Someday My Prince Will Come.” The bassist nodded my way. Maybe I was making too much eye contact or something, and just as I figured I had overstayed my welcome in front of the combo, Dad approached beaming with his group of conference friends. He wore a green jacket that made him look like he’d won the Master’s Tournament. We embraced. Then taking in my get-up, he grew glum. “Did you have to come here looking like this?” he asked. Nevertheless, Dad introduced me to his colleagues. I wondered which guy possessed the famous Playboy Club key.

“Comparative literature, what’s that? What do you do with that?” asked one associate who smelled like English Leather and still sported his conference tag.

“My sentiments exactly,” said Dad, merrily.

America was in the post-oil embargo recession. People with Ph.D.’s were cleaning zoo cages. But as I suspected, the progeny of my father’s business associates were forging forward. The colleagues bragged about their sons and daughters in medical, dental, and law school. How surprised I was when one of Dad’s colleagues drew me aside and told me that I was a very good sport to meet my father here. He said that his daughter would never set foot in a Playboy Club. “She’d scream bloody murder if I asked.”

A Bunny in a tan corset came up to take our drink order, and when my dad put his arm around her waist she pressed on a smile and removed my dad’s hand. Then she pretended to see a customer across the room and slid off into the forest of patrons.

“You’re not supposed to touch the merchandise,” said one of the colleagues, his voice dry as a martini.

“These girls? It doesn’t mean anything to them. That’s part of the game,” Dad replied.

The other guy shrugged with a suit-yourself look.

It took a long time before another Bunny came up. And the one who appeared was slightly less glamorous than the rest. She wore a blue corset. Her ears drooped. Her gray eyes looked a little weary, but behind her frosted pink lipstick and pressed-on smile, she also seemed more serious. When she took my drink order (a gin and tonic) she met my eyes with a knowing sisterly look.

Returning, the blue Bunny had only one drink on her tray and that drink was my G&T. She asked me if I were in college and told me that she was at Circle Campus, putting herself through school, studying social work. The Bunny job really helped. The money was decent, and she could go to classes during the day. I wondered when she had time to study, but I didn’t ask.

“Your plan is super,” I told her. “You’re so independent.”

“I have to be,” she replied.

I admired her. I was in awe of her self-reliance. I thought of how she would be helping others in her future job as a social worker. Most of all, I considered how tough things were for her. How easy they were for me. I glanced over at my dad in his green jacket. He was listening closely to something an associate was explaining. I felt mercenary and somewhat ashamed of it. I thought of what a small price I had to pay for money. How steady, if imperfect, was my father’s love. • 20 February 2013